Vermilion Point facts for kids

|

|

| Location | Whitefish Township, Chippewa County, Michigan, USA |

|---|---|

| Coords | 46°45′47″N 85°08′56″W / 46.76306°N 85.14889°W |

| Organization | Little Traverse Nature Conservancy |

| Historic use | Vermilion Lifesaving Station 1877 - 1944 |

| Modern use | Vermilion Point Nature Conservancy |

| Website | www.landtrust.org |

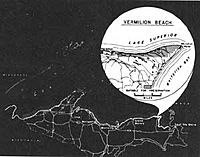

Vermilion Point is a quiet, natural area in Chippewa County, Michigan, United States. It is about 10 miles (15.7 km) west of Whitefish Point. This historic spot is on the southeast coast of Lake Superior. This part of the lake is sometimes called the "Graveyard of the Great Lakes" because many ships wrecked there.

Brave rescuers worked at the Vermilion Lifesaving Station from 1877 to 1944. They saved people from shipwrecks along this dangerous coast. Later, new technology like radar made their job less needed, so the station closed.

Vermilion Point was a popular resting spot for Native Americans and early explorers. People who settled there grew cranberries in the wet areas. These berries were sent to cities like Chicago, Illinois and Duluth, Minnesota. Today, it is a protected nature preserve. Scientists study birds, especially the piping plover, and how beach plants grow here.

Contents

Nature and Landscape

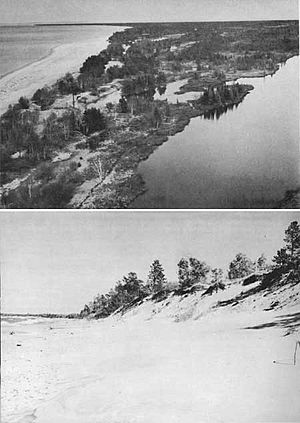

The beach at Vermilion Point has sand and small stones. You can sometimes find agates here, especially after storms. Strong waves and winds keep the low sand dunes near the beach from having many plants. Behind these dunes, you will find wet areas like swales, bogs, and marshes.

Vermilion Point used to be a peninsula, a piece of land almost surrounded by water. Now, it is not a peninsula anymore. Sand Creek, which flows from the surrounding wetlands into Lake Superior, is the only main natural feature left. The original trees were cut down long ago. Now, the area has typical northern hardwood and conifer trees.

Early History of Vermilion Point

Vermilion was named for the red (vermilion) colored clay found nearby. Native Americans used this clay for paint. There is no sign that Native Americans lived here all the time. But it was a popular stop for them and for early European travelers. These included Voyageurs and trappers.

Jesuit missionaries were likely the first Europeans to visit Vermilion in the 1600s. In 1820, territorial governor Lewis Cass and Indian Agent Henry Schoolcraft passed through Vermilion Point. They were on an official trip along Lake Superior's south shore. Henry Schoolcraft also stayed overnight at Vermilion in 1831 to escape a storm. He was leading a group to give vaccinations to Native Americans.

The Life-Saving Station

The Vermilion Lifesaving Station opened in 1877. It was on the Lake Superior coast, known for many shipwrecks. More ships started wrecking after the Soo Locks opened in 1855. The United States Life-Saving Service built three other stations nearby. These were at Crisp Point Light, Deer Park, and Two Hearted River. Vermilion is the only one of these four stations that still has some of its original buildings.

The men who worked at Vermilion Lifesaving Station faced very tough conditions. Some even called it the "Alcatraz" of the Life-Saving Service. Life for the workers and their families was lonely and often boring. This changed when dangerous rescue missions happened in stormy seas. For many years, there were few roads. Supplies came by boat. In the snowy winters of the 1930s, mail was delivered by dog sled.

The Vermilion surfmen were very skilled. They trained hard with special lifeboats that could empty water and right themselves. Because of their skills, the United States Life Saving Service chose them. They showed off their life-saving techniques at the St. Louis World Fair in 1904.

The United States Life-Saving Service joined with the U.S. Coast Guard in 1915. Later, bigger freighters (cargo ships) and better weather forecasts made sailing safer. New tools like radio and radar also helped. During World War II, the Coast Guard decided that these life-saving stations were no longer needed. The Vermilion Life Saving Station was first combined with the Crisp Point station in 1940. It finally closed completely in 1944.

Cranberry Farming

The low, wet lands at Vermilion Point were perfect for growing cranberries. Workers divided the wet areas with dirt walls. They also built a dam on Sand Creek. They harvested cranberries by using special forks to comb the vines. The ripe cranberries floated in the water and were scooped up.

The cranberries were then moved by flat-bottomed boats to a water wheel on Sand Creek. This wheel lifted them onto a conveyor belt that led to a mill. After sorting, the cranberries were packed for shipping or made into jelly. They were then put on small trolley cars. These cars went down a tramway to Lake Superior. From there, the cranberries were loaded onto small boats and then onto a steamer waiting offshore. The cranberries were shipped to cities like Chicago and Duluth.

Cranberry farming at Vermilion Point lasted from 1887 to 1932. The most cranberries were produced between 1888 and 1910. In 1897, Vermilion Point produced 1,600 bushels of cranberries. Today, the old dirt walls are still there. But beaver dams have flooded the wet areas. You can still find cranberries growing along the edges of the wet areas and the beach.

Changes Over Time

When the Coast Guard closed the station, they left behind some old equipment from 1876. Local people damaged some of this equipment. In 1947, the station was sold to private owners for $17,000. Reports say that motorcycle groups visited the station in the 1950s. In the 1960s, "hippies" sometimes stayed there in the summer. In the 1970s, four-wheel drive vehicles and snowmobiles damaged much of the beach grass around the old station.

Vermilion Today

In the early 1970s, the Vermilion Life Saving Station and about 1.5 miles (2.4 km) of undeveloped shoreline were bought by private owners. They wanted to protect and restore the area. Vermilion Point is one of the few places on the Great Lakes where the piping plover has successfully nested.

By 2004, the land was given to the Little Traverse Conservancy. It is now called the Vermilion Point Nature Preserve. Lake Superior State University, the Whitefish Point Bird Observatory, and the Michigan Audubon Society use it for research. They study the endangered piping plover and how beach plants grow. Students also get hands-on experience in studying birds. The preserve is open to the public for quiet activities like walking. No motorized vehicles are allowed. Areas around piping plover nests and bird-trapping nets are protected and cannot be entered.

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |