William George Malone facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

William George Malone

|

|

|---|---|

Lieutenant Colonel William Malone

|

|

| Born | 24 January 1859 Kent, England |

| Died | 8 August 1915 (aged 56) Chunuk Bair, Gallipoli, Ottoman Turkey |

| Allegiance | New Zealand |

| Service/ |

|

| Rank | Lieutenant colonel |

| Commands held | Wellington Infantry Battalion |

| Battles/wars | First World War |

| Awards | Mentioned in Dispatches (2) |

William George Malone (born January 24, 1859 – died August 8, 1915) was a brave officer from New Zealand. He served in the First World War and led the Wellington Infantry Battalion. This group of soldiers was part of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force.

Malone was a key leader during the Gallipoli Campaign. Sadly, he was killed in action during the fierce Battle of Chunuk Bair. This happened when he was hit by friendly fire, meaning fire from his own side.

Born in England, Malone moved to New Zealand in 1880. He joined the New Zealand Armed Constabulary. Later, he became a farmer and then a lawyer. He was also very active in the local military.

When the First World War began, he volunteered to serve. He was chosen to command the Wellington Infantry Battalion. He trained his soldiers in Egypt and led them bravely in the Gallipoli Campaign until his death.

| Top - 0-9 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z |

William Malone's Early Life and Education

William George Malone was born in a village called Lewisham in Kent, England. He was born on January 24, 1859. He was the second of five children. His father, Thomas Malone, was a chemist. He worked for a famous photography pioneer, Henry Fox Talbot.

When William was only eight years old, his father passed away. This made things financially tough for his family. William went to school at St. Joseph's College in London. He also studied at Marist boarding schools in England and France. Because of this, he learned to speak French very well.

After finishing school in 1876, William worked in an office in London. He also started his military journey. He joined the City of Westminster Rifle Volunteers. Later, he served in the Royal Artillery Volunteers for a while.

Life and Work in New Zealand

William Malone moved to New Zealand in January 1880. His older brother, Austin, was already there. Austin was serving in the New Zealand Armed Constabulary. Just one month after arriving, William joined his brother in the Constabulary. Both brothers were based in Ōpunake, in the Taranaki region. William was part of an event where the village of Parihaka was entered on November 5, 1881.

Farming and Family Life

After two years, Malone left the Constabulary. He started working with surfboats, which helped unload cargo at Ōpunake. He and his brother bought a large area of bush country near Stratford. They started farming there. In just a few years, their land became very productive.

His mother and two sisters also moved to New Zealand to join them in Stratford. William also became involved in the local military group, the Stratford Rifles. In 1886, Malone married Elinor Lucy Penn. They had five children together: one daughter and four sons.

Malone was very active in his community. He was a member of the Hawera County Council. He also served on the Taranaki Hospital and Charitable Aid Board. From 1890, he also worked as a land agent. He helped start the Stratford County Council. He was its first clerk and treasurer from 1891 to 1900.

Becoming a Lawyer

Malone began studying law. He became a solicitor in 1894 and a barrister five years later. In 1903, he and his family moved to New Plymouth. He started a law firm with James McVeagh and William Anderson. Their firm mainly handled land deals. They opened several law offices around the Taranaki region.

Sadly, Malone's wife Elinor died in childbirth on June 18, 1904. Their baby son also passed away. The next year, Malone married Ida Katharine Withers. Ida had been a friend of Elinor's and had also tutored his children. William and Ida had three more children together.

Involvement in Politics and Military

Malone became interested in politics. He tried to become a Member of Parliament in 1907. He ran as an Independent Liberal for the Taranaki area. He did not win, coming in last among three candidates. The next year, Joseph Ward, leader of the Liberal Party, asked Malone to be their candidate. Malone said no. He had some different ideas from the Liberal Party. He ran again as an independent but did not win.

In 1911, Malone sold his part of the law firm. He moved back to Stratford. He started his own law firm in November 1911. He hired another solicitor, Cyril Croker, as his clerk. With less work, Malone focused more on his other interests, especially the military.

Malone was part of New Zealand's local military, called the Volunteer Force. In 1900, he helped create the Stratford Rifle Volunteers. He became its captain. When he moved to New Plymouth in 1903, he gave up his command. Later, he became an adjutant for the 4th Battalion. By 1910, he was a lieutenant-colonel and commanded the battalion.

The next year, the Volunteer Force was replaced by the Territorial Force. Malone was put in charge of a new unit, the 11th Regiment (Taranaki Rifles). During this time, he introduced the "lemon squeezer" hat to the Territorial Force. His soldiers shaped the hat to look like Mount Taranaki. This helped rain run off the hat easily. Later, the lemon squeezer hat became the official hat for the New Zealand Military Forces.

William Malone in the First World War

Malone had believed for a long time that a big war was coming. He prepared himself by studying military history and training hard. He even slept on a military camp bed to get ready. When the First World War started, he volunteered to serve. Because he was well-respected, he was made commander of the Wellington Infantry Battalion. This battalion was part of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force (NZEF).

The battalion left Wellington in October 1914 and sailed to Egypt. There, they mostly trained. In January 1915, they were sent to the Suez Canal. They helped guard against a possible attack from the Turkish army. After three weeks of guard duty, they returned to Cairo.

The Gallipoli Campaign

By this time, the New Zealand and Australian Division was getting ready for operations in the Dardanelles. Malone's battalion joined the New Zealand Infantry Brigade. In April, the division, now part of the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC), sailed to Gallipoli. The Wellington Battalion landed at Anzac Cove on the afternoon of April 25. They then moved up to Plugge's Plateau.

On April 27, Malone's battalion was asked to help strengthen positions held by Australian soldiers. These positions were on a place later called Walker's Ridge. The Turkish army had launched a counterattack. Malone quickly set up a new defensive line. He was frustrated by poor decisions made by another commander. Malone asked to take full charge of the position, and his request was approved. In the following days, he worked his men hard to make the defenses stronger.

In early May, the ANZAC positions were stable. The New Zealand Infantry Brigade moved to Cape Helles for more operations. Malone led his battalion during the Second Battle of Krithia. He disagreed with his brigade commander, Colonel Francis Johnston, about a bayonet charge. Malone felt that British officers were too rigid in battle. Later, Malone was praised for his work at Cape Helles.

By late May, the brigade was back at ANZAC Cove. On June 1, the Wellington Battalion moved to the front lines at Courtney's Post. Malone was in command. He immediately worked to improve the position. He fixed neglected defenses and set up a team of snipers. This helped his men gain control over the area between the trenches.

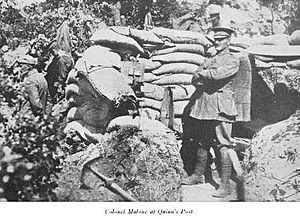

Malone's efforts impressed his commanders. On June 9, the Wellington Battalion was given the task of holding Quinn's Post. This was a very exposed position, often only 10 meters from Turkish trenches. Malone immediately started making it safer. They built terraces, dugouts, and used many sandbags for protection. He also set up machine gun posts to increase their firepower. Malone demanded a lot from his men, but he also cared deeply about their well-being. General William Birdwood praised Malone for his excellent work at Quinn's Post.

The Battle of Chunuk Bair

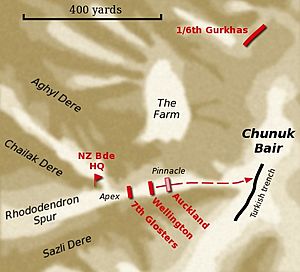

In August, the Allied forces planned a major attack to break out of the ANZAC area. A key goal was to capture the Sari Bair Range, especially Chunuk Bair. On August 7, the New Zealand Infantry Brigade began its attack. However, delays meant the attack started in daylight instead of at night. This caused many losses for another battalion.

Colonel Johnston, Malone's commander, then ordered Malone to take his battalion forward. Some accounts say Malone refused to attack in daylight, arguing his battalion could take Chunuk Bair that night. However, more recent research suggests Malone was arguing with a junior officer earlier that day, not directly refusing Johnston's order to attack later. Malone preferred to set up defenses and wait for nightfall for a safer attack.

In the early morning of August 8, the Wellington Battalion successfully captured Chunuk Bair. They had support from other troops and heavy artillery fire. Malone's battalion was the only one still strong in the New Zealand Infantry Brigade. He worked to secure the top of Chunuk Bair. It was hard to deepen the captured Turkish trenches. As the sun rose, Turkish soldiers on a nearby hill could easily shoot at the Wellingtons. This caused many casualties.

Malone kept coordinating the defenses. He led bayonet charges against many Turkish attacks. The trenches became filled with bodies, reducing the little cover they had. In the early evening, around 5 PM, Malone was killed in his headquarters trench. He was hit by friendly fire, possibly from his own artillery or naval guns.

Later that evening, reinforcements arrived. The remaining soldiers of Malone's battalion withdrew. They had lost 690 men killed or wounded out of 760. Malone, along with 300 of his men, has no known grave. Two days later, Chunuk Bair was lost to the Turks. A memorial service for Malone was held on August 21. Almost all the surviving men of his battalion attended. Malone was again praised for his leadership during the August offensive.

Malone left behind his wife, Ida, and eight children. His farming income decreased in the 1920s, and Ida faced financial difficulties. She eventually moved to England with three of her children and one daughter from Malone's first marriage. She died there in 1946. Four of Malone's oldest sons also served in the NZEF. One son, Maurice, received the Distinguished Conduct Medal. Another son, Edmond, received the Military Cross and died in 1918 after being wounded.

William Malone's Lasting Legacy

After the Battle of Chunuk Bair, some people criticized Malone's defense plans. However, later studies showed that these criticisms were unfair. There were bigger mistakes made by commanders higher up. For example, delays in sending reinforcements to Chunuk Bair after it was captured likely led to its loss.

In New Zealand, Malone's death was widely reported and deeply felt, especially in the Taranaki region. The soldiers of the Wellington Regiment greatly respected their former commander. They paid for the construction of the Malone Memorial Gates. These gates are at the entrance to King Edward Park in Stratford, Taranaki.

The gates are one of New Zealand's largest war memorials for a single soldier. They were designed by Duffil & Gibson and opened on August 8, 1923. An annual ceremony is held at the gates on August 8 to remember Malone. A play about the Wellington Battalion's battle, called Once on Chunuk Bair, featured a character based on Malone. This play was made into a film called Chunuk Bair in 1992. In 2005, a plaque honoring Malone was put in the New Zealand Parliament's Grand Hall. His Memorial Plaque is kept at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa.

| Ernest Everett Just |

| Mary Jackson |

| Emmett Chappelle |

| Marie Maynard Daly |