Willis R. Whitney facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Willis R. Whitney

|

|

|---|---|

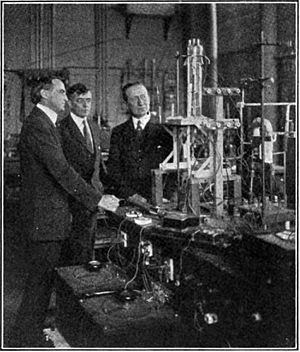

Whitney as a MIT faculty member

|

|

| Born | August 11, 1868 |

| Died | January 9, 1958 (aged 89) |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | General Electric Company |

| Spouse(s) | Evelyn Jones Whitney |

| Children | Evelyn Van Alstyne Schermerhorn |

| Awards | Willard Gibbs Award (1916) Perkin Medal (1921) IEEE Edison Medal (1934) Public Welfare Medal (1937) John Fritz Medal (1943) IRI Medal (1946) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | chemistry, inorganic chemistry, electrochemistry |

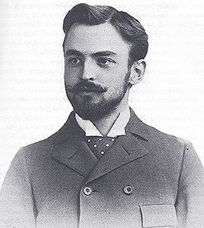

Willis Rodney Whitney (born August 22, 1868 – died January 9, 1958) was an American chemist. He is famous for starting the research laboratory at the General Electric Company (GE). People often call him the "father of industrial research" in the United States. He helped bring together the worlds of science research and industry. Before this, these two areas were very separate. Whitney also created an important theory about how iron rusts. He developed this idea after studying at M.I.T. and the University of Leipzig. He was a professor at M.I.T. before he became a research director. Whitney received many awards for his work, including the Willard Gibbs medal and the Edison medal. He strongly believed that research and experiments should be fun.

Contents

Willis Whitney's Early Life

Whitney was born in Jamestown, New York. His parents were John Jay Whitney and Agnes Whitney. From a young age, Willis was very curious. He loved to ask "why" and often did experiments at home. For example, he wondered why tree bark grew stronger on one side. He also compared pigeon and chicken talons.

His interest in tiny things grew after he took a free YMCA class. A local mill owner, William C.J. Hall, taught the boys how to use a microscope. Whitney also learned about business from his father, who made furniture. Willis and his friends started a junk-collecting business. They would gather scraps, then sell them when prices were high. They even bought bicycles to collect more junk!

Meeting Evelyn

Willis met Evelyn Jones when they were young. She had lost a nickel and was upset. Willis helped her find it. They started spending more time together. Willis wanted a bicycle to ride with her. But he also wanted a microscope. He bought the microscope first, then the bicycle. Later, Willis and Evelyn got married. They had a daughter named Evelyn, born in 1892.

Faith and Family

As a child, Whitney was very religious. He taught Sunday school in Boston's Chinatown while at M.I.T. Even as he grew older, he kept his faith. When his father passed away, Whitney returned home to comfort his mother. She was slowly losing her eyesight. After her sight was completely gone, she seemed very calm. Whitney visited her often until she died in 1927.

Famous Friends

Whitney met many famous scientists during his life. He attended a special lunch for Madame Curie. There, he also met Thomas Edison, Robert Millikan, and Arthur Compton. Later, he visited J.J. Thomson at Cambridge University in Europe. He even got to see Madame Curie's laboratory.

Retirement and Hobbies

After retiring, Whitney spent more time on his favorite activities. He enjoyed bicycling, doing experiments, and collecting arrowheads. He even studied neurology and welding just for fun!

Tough Times

During the Great Depression, which started in 1929, Whitney faced a difficult time. He felt very sad because he had to let go of many workers at his lab. Businesses were unsure if research was worth the money. The GE Research laboratory's future was questioned. Whitney took a vacation to feel better. He did manual work at home and visited places like Florida. When he returned, he decided to step down as the lab director. He lived to be 89 years old.

Willis Whitney's Education

Studying at M.I.T.

Whitney first wanted to study biology. By chance, he visited M.I.T. on the day of entrance exams. He was curious and asked to take the test. He passed without studying! He chose M.I.T. because of its great laboratories. Whitney worked hard but worried about knowing too little. He didn't pick a major right away. The president of M.I.T. told him to focus on chemistry or biology. Whitney talked with his friends, and finally chose chemistry.

At M.I.T., Whitney met Arthur A. Noyes, a chemistry assistant. Noyes's work with solutions inspired Whitney. Before graduating in 1890, Whitney became an Assistant Instructor of Chemistry. He taught general chemistry and then analytical chemistry. He liked to teach students by giving them problems to solve through research. This was different from how the school usually taught. After four years, Whitney decided to go to the University of Leipzig in Germany. He wanted to earn his doctorate there.

Doctorate at Leipzig University

In Germany, Whitney studied under Wilhelm Ostwald. His main project was about how colors change during chemical reactions. He also translated a textbook on electrochemistry. In 1896, Whitney finished his work and earned his doctoral degree. He then spent about six months in France. He studied organic chemistry at the Sorbonne.

How Iron Rusts: Whitney's Theory

After returning from Germany, Whitney continued working with Arthur Noyes. He became very interested in why metal rusts. He had seen rust problems in water pipes at a Boston hospital. Many people thought that carbonic acid was needed for rust to form. Whitney wanted to test this idea.

He set up an experiment using a physical chemistry approach. He thought that rusting must be an "oxidation-reduction" reaction. This is similar to how a battery works. He put pieces of iron in sealed water bottles. He made sure there was no air, acid, or alkali in the water. He sealed the bottles with wax. For weeks, no rust formed. Then, he opened the bottles and let air in. Almost immediately, the water turned yellow, and rust appeared.

Whitney realized that the iron must have dissolved into the water before he opened the bottle. This happened because of hydrogen ions. To check his idea, his students did more research. One student opened a rusty radiator and lit a match. Hydrogen gas was present, just as Whitney's theory predicted!

Basically, Whitney found that rust happens when there's proper electrical contact between parts of the metal and hydrogen ions. He also discovered that keeping iron in an alkali solution could stop it from rusting. He published his findings in 1903. While another scientist had published a similar idea earlier, Whitney helped make this theory widely known in America.

Working with Eastman Kodak

One day, George Eastman from Eastman Kodak asked Arthur Noyes and Whitney for help. Eastman's company was wasting a lot of alcohol and ether vapor when making photographic paper. He needed a way to save these materials and lower costs.

After a few weeks, Noyes and Whitney found a solution. They figured out how to collect the vapors and turn them back into useful liquids. In 1899, they signed a contract with Eastman Kodak. The company paid them well, funded half a laboratory, and gave them company stock. At that time, it was unusual for university scientists to work so closely with businesses.

General Electric Research Lab

In 1900, Willis Whitney received an offer from Edwin W. Rice and Elihu Thomson of General Electric (GE). They wanted him to lead their new Electric Research Laboratory. Whitney loved teaching and turned them down many times. Finally, Rice suggested that Whitney could try working at GE without leaving M.I.T. He could travel between the two places until he decided. Whitney accepted this offer. On one of his first days, he met Charles Steinmetz, another brilliant scientist. Whitney was eager to create something useful for GE.

The Electric Furnace

One of Whitney's first challenges at GE was making a furnace that could produce perfect porcelain rods. Many rods were being wasted because the old furnaces had uneven temperatures. Whitney experimented with different materials. He found that he could make a good furnace by running a controlled electric current through a wire wrapped around a carbon pipe. This new furnace could produce perfect porcelain rods almost every time. GE quickly started using his design.

Improving Light Bulbs: G.E.M. Lamps

After his success with the furnace, Whitney worked on making better light bulbs. The carbon filaments in light bulbs at the time burned out quickly at high temperatures. To make them last longer, they had to be kept at lower temperatures, which meant less light. GE needed to improve its bulbs to compete with other companies.

Whitney brought in former M.I.T. students and scientists from other countries. In December 1903, he found a solution. He used his electric furnaces to heat the carbon filaments to very high, controlled temperatures. This made the carbon filaments form a special graphite layer. This layer had metal-like properties. It allowed the lamp to run hotter and last longer. These new bulbs were called "General Electric Metallized" lamps, or "G.E.M." lamps. Soon after, in May 1904, Whitney left M.I.T. to become the full-time director of the GE Research Laboratory.

Even Better Bulbs: Tungsten Lamps

Other companies soon created new light bulbs with tantalum filaments. This put pressure on GE again. Whitney and his team started looking at other elements. They found that tungsten would be best, but it was very brittle. Whitney asked William D. Coolidge, another former student, for help. Coolidge was also a professor at M.I.T. and didn't want to leave his research. Whitney offered him the same deal he had received: try it out without full commitment.

Coolidge eventually found a way to make strong tungsten filaments. He used a special binder that would disappear when the filament was heated, leaving pure tungsten. Whitney traveled to Germany to learn about their tungsten lamp work. When he returned, he told his team that GE had bought a German patent. But he believed Coolidge's process would be better in the long run. By December 1907, Coolidge perfected the process, and the tungsten filaments went into mass production. These new tungsten lamps were much better than the G.E.M. lamps and soon replaced them.

Solving the Blackening Bulb Mystery

After recovering from an illness, Whitney met Irving Langmuir, a young chemistry professor. Langmuir came to GE for summer research. He wondered why light bulbs turned black after use. He started working on this problem right away. After the summer, Langmuir felt he hadn't made enough progress and wanted to leave. But Whitney told him to stay as long as he was having fun. Whitney would handle the paperwork.

Three years later, in 1913, Langmuir had a breakthrough. He found that the blackening was caused by the tungsten filament evaporating onto the glass. He discovered that adding a gas, like argon, to the bulb could slow this evaporation. This was another huge step for the lamp industry. The new lamps, using Coolidge's tungsten and Langmuir's gas-filling, were called "Mazda C Lamps."

The Inductotherm Device

One day, some young lab assistants complained about feeling sick after working near high-frequency equipment. Whitney was skeptical but let them go home. The next day, a doctor also felt ill near the equipment. Whitney then experimented with cockroaches and mice, raising their body temperatures with the high-frequency device. He even cured a sick dog!

Whitney remembered a doctor who used fevers to treat brain disorders. Before trying the device on people, he tested it on himself. It relieved his stiff shoulder pain. He then worked with hospitals to develop the device further. This device used vacuum tubes to create electromagnetic waves. Whitney wrote a paper explaining how it worked. GE's X-Ray corporation then sold it as the "Inductotherm." This device is a type of diathermy machine, used for heating body tissues. For this invention, Whitney received the French Legion of Honor award.

Other Important Projects

Many other projects happened at the GE lab under Whitney's leadership. Coolidge developed a better X-ray tube in 1913. Scientists also worked on improved electrodes, lightning arresters, and insulating materials. They even worked on electric blankets!

Whitney didn't work on every project directly. But he often came up with ideas and encouraged his employees to explore them.

How Whitney Led Research

As the director of the GE Research Laboratory, Whitney had many responsibilities. He hired and fired employees, read scientific journals, and attended conferences. He believed in teamwork and held weekly meetings called "colloquia." In these meetings, researchers shared their progress, problems, and new ideas. Whitney also checked in with everyone daily. He offered advice, encouragement, or just said hello. He wanted to build a strong team spirit.

Whitney looked for researchers who loved to experiment and had strong ideas. He is known as the "founding father of industrial research" because of his leadership style. He had three main ideas for directing research:

- All inventions would belong to GE, but the credit would go to the researcher.

- Each person should be allowed to use their unique strengths.

- A research director should always be hopeful. Whitney believed that even research without a clear goal could lead to great discoveries.

During tough economic times, the GE Laboratory focused more on short-term goals. But they always kept one or two big projects going. When the stock market crashed in 1929, Whitney had to let many employees go. This made him very sad. He took a six-month break to recover. In 1932, he retired, and William Coolidge became the new director. Under Whitney, the GE Laboratory successfully combined industry and research. It became known as the "House of Magic."

Whitney's Patents

Willis Whitney filed many patents while working at GE. He also told his employees to write everything in their lab notebooks. This helped prove their ideas in case of patent disputes. Any new invention ideas had to go to Whitney first. He would decide if the idea could make money. Then, he would send it to GE's patent department.

Some of the patents Whitney filed as an inventor include:

- A device and method for electric vapor.

- An improved version of that device.

- A device to control refrigerant flow.

- A moisture indicator.

- An apparatus and method for purifying water.

- A device and method for disposing of soot.

- A photoelectric system.

- A method for making crucibles.

- A composite metal gear.

- A process for creating a matte finish.

These are just a few of the many patents Whitney helped create. His connections with GE's patent department helped new inventions get patented quickly.

During World War I, Josephus Daniels created a Naval Consulting Board. Whitney was asked to join it. This board, led by Thomas A. Edison, looked at new ideas for the Navy. Whitney became the head of the chemistry and physics sections. He was put in charge of research for making nitrates at Muscle Shoals.

Using his connections, Whitney helped build an experimental submarine detection station. Irving Langmuir, who also joined the board, led this station. William Coolidge experimented with rubber tubing there. Eventually, Coolidge developed the "C-tube," a rubber tube with metal that could find submarines up to two miles away. Later, Dr. Hull and his team improved this to the "K-tube," which could detect submarines up to ten miles away.

Whitney's Philosophy

Whitney loved to research and experiment just for fun. He didn't like paperwork. His weekly lab meetings were informal. He often asked his employees if they were "having fun." He strongly believed in "serendipity," which means making happy discoveries by accident. He often said, "Necessity is not the mother of invention. Knowledge and experiment are its parents."

Whitney wrote articles and gave speeches encouraging more interest in research. He felt that too few chemists in the U.S. were actually doing research. After meeting Marie Curie, Whitney helped set up funding for future scientists. He helped create the Gerard Swope Loan Fund for GE employees and the Steinmetz Memorial Scholarship. The GE lab also had a "test" program where college students could work there and attend college at night.

Fun Experiments and Hobbies

Besides his work, Whitney did many experiments just for enjoyment.

Tracking Turtles

Around 1912, Whitney started focusing on his hobby of tracking turtles. He wrote down where and when he saw them. He even marked their shells to follow them. Once, he watched a turtle lay eggs. A skunk tried to eat them, so Whitney scared it away. Later, he and his wife watched the baby turtles hatch. He learned that turtles like bananas and migrate to the same spot every year. He also found that you could tell a turtle's age by the rings on its shell. During the Great Depression, Whitney would give children a quarter for every turtle they brought him.

Vacuum Fly Experiment

Someone once asked Whitney if insects could live in a vacuum. He asked his employees to try the experiment, but they thought it was pointless. So, Whitney did it himself. He put a cockroach and a fly in a vacuum chamber. They stopped moving. After a while, he slowly let air back in, and both insects started moving again!

Freezing Water

Whitney enjoyed reading scientific journals. He read an article that said "Roger Bacon Was Mistaken" about hot water freezing faster than cold water. Whitney decided to test it. He thought that heating water removes dissolved things, which should make it freeze faster. He put trays of hot and cold water in his freezer. He found that the hot water froze much more than the cold water. He published his own article about this in 1946.

Whitney's Crib

One summer, Whitney was on Lake Chautauqua. He noticed a shallow area in the middle of the lake. He got out of his friend's boat and explored it. He got an idea: to build an island! He hired a team and filled a large area with rocks. The next summer, the island was finished. Whitney put up a flag and got a deed for the property in 1899. The island is now known as Whitney's Crib.

Memberships and Awards

Willis Whitney was part of many important groups and received many honors.

Memberships and Positions

- Translator of M. Le Blanc's Electro-Chemistry (1896)

- Member and President of the American Chemical Society (1909)

- Member and President of The American Electrochemical Society (1911–1912)

- The U.S. Naval Consulting Board (1915)

- The National Academy of Sciences (Elected 1917)

- The Advisory Committee to the National Bureau of Standards (1925-1930)

- Honorary Vice President of G.E. (1932)

- Director of G.E. Research Laboratory (1900-1928)

- Vice President of G.E. in charge of research (1928- 1941)

- The American Institute of Electrical Engineers

- The American Physical Society

- The American Philosophical Society

- Honorary Member of the American Steel Treaters' Society

- The French Legion of Honor

- Trustee of the Albany Medical College

- Emeritus Member of the Corporation of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Associate Editor of the Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry

Awards and Titles

- Willard Gibbs Medal Recipient (1916)

- Honorary Doctor of Science from Union College (1919)

- Chandler Medal (1920)

- Perkin Medal Recipient (1921)

- Honorary Doctor of Science from Syracuse University (1926)

- Honorary Degree from the University of Michigan (1927)

- Public Welfare Gold Medal of the National Institute of Social Sciences (1928)

- Franklin Medal of the Franklin Institute (1931)

- Edison Medal "for his contributions to electrical science, his pioneer inventions, and his inspiring leadership in research" (1935)

- Decoration of Chevalier of the French Legion of Honor (1937)

- Public Welfare Medal from the National Academy of Sciences (1938)

- John Fritz Medal Recipient (1943)

- First recipient of the IRI Medal from the Industrial Research Institute (1946)

- First recipient of the Willis Rodney Whitney Award from the National Society of Corrosion Engineers

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |