Robert Andrews Millikan facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Robert A. Millikan

|

|

|---|---|

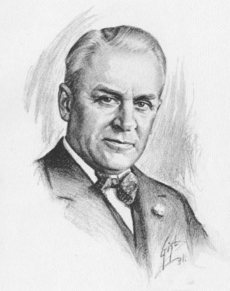

Millikan in the 1920s

|

|

| 1st President of the California Institute of Technology | |

| In office 1920–1946 |

|

| Succeeded by | Lee Alvin DuBridge |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Robert Andrews Millikan

March 22, 1868 Morrison, Illinois, U.S. |

| Died | December 19, 1953 (aged 85) San Marino, California, U.S. |

| Alma mater | |

| Known for |

|

| Spouse(s) | Greta (née Blanchard) |

| Children |

|

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physics |

| Institutions | |

| Thesis | On the polarization of light emitted from the surfaces of incandescent solids and liquids. (1895) |

| Doctoral advisor |

|

| Other academic advisors | Mihajlo Pupin Albert A. Michelson Walther Nernst |

| Doctoral students |

|

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ |

United States Army |

| Years of service | 1917–1918 |

| Rank | Lieutenant Colonel |

| Unit | Aviation Section, U.S. Signal Corps |

| Signature | |

Robert Andrews Millikan (born March 22, 1868 – died December 19, 1953) was an American physicist. He won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1923. He earned this award for two main reasons:

- He measured the exact charge of a single electron.

- He studied the photoelectric effect, which is how light can make electrons move.

Millikan finished college at Oberlin College in 1891. He then earned his PhD from Columbia University in 1895. In 1896, he started working at the University of Chicago. He became a full professor there in 1910.

In 1909, Millikan began experiments to find the charge of a single electron. He first used charged water droplets in an electric field. The results hinted that the charge on the droplets was a multiple of a basic electric charge. But the experiment was not precise enough. In 1910, he got much better results with his famous oil-drop experiment. He used oil instead of water because water evaporated too quickly.

In 1914, Millikan also worked on testing Albert Einstein's idea about the photoelectric effect. Einstein had described this effect in 1905. Millikan's research helped him find a very accurate value for Planck’s constant. In 1921, Millikan moved from the University of Chicago. He became the director of the Norman Bridge Laboratory of Physics at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) in Pasadena.

At Caltech, he studied radiation coming from outer space. This radiation had been found by physicist Victor Hess. Millikan proved that this radiation truly came from outside Earth. He named it "cosmic rays". From 1921 until he retired in 1945, Millikan led Caltech. He helped make it one of the top research schools in the United States.

Robert Millikan's Life and Work

Early Life and Education

Robert Andrews Millikan was born on March 22, 1868, in Morrison, Illinois. He went to high school in Maquoketa, Iowa. He earned his first degree in classics from Oberlin College in 1891. Then, he got his doctorate in physics from Columbia University in 1895. He was the first person to earn a PhD from that physics department.

Millikan loved teaching and learning throughout his life. He helped write popular science textbooks for students. These books were special because they explained physics in a way that real physicists thought about it. They also had many homework problems that made students think, not just plug numbers into formulas.

Measuring the Electron's Charge

Starting in 1908, Millikan worked on his famous oil drop experiment. He was a professor at the University of Chicago at the time. In this experiment, he measured the charge of a single electron. Before this, J. J. Thomson had already found the ratio of an electron's charge to its mass. But the actual values for the charge and mass were still unknown. If one value could be found, the other could be figured out easily.

Millikan and his student Harvey Fletcher used the oil-drop experiment to find the electron's charge. They also used it to calculate the electron's mass and Avogadro's number. Millikan took all the credit for this work. In return, Harvey Fletcher was allowed to be the sole author of a related paper for his own degree. Millikan later won the 1923 Nobel Prize in Physics partly for this work. Fletcher kept their agreement a secret until he died.

After Millikan published his first results in 1910, another physicist named Felix Ehrenhaft made different observations. This led to a disagreement between them. Millikan improved his experiment and published his important study in 1913.

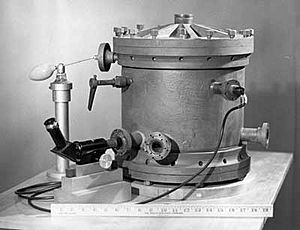

The elementary charge is a very basic physical constant. Knowing its exact value is very important in physics. Millikan's experiment measured the force on tiny charged oil droplets. These droplets were held still against gravity between two metal plates. By knowing the electric field, he could figure out the charge on each droplet. He did the experiment many times with different droplets. Millikan showed that the charges were always whole number multiples of a single, common value. This value (1.592 × 10−19 coulomb) was the charge of one electron. The modern value is slightly different (1.602 176 53(14) x 10−19 coulomb). This difference is likely because Millikan used a slightly wrong value for how thick air is.

When Millikan did his oil-drop experiments, scientists were starting to understand that there were tiny particles smaller than atoms. But not everyone was convinced. In 1897, J. J. Thomson had found negatively charged "corpuscles" (what he called electrons) by experimenting with cathode rays. These particles had a charge-to-mass ratio much smaller than a hydrogen ion. Other scientists like George Francis FitzGerald and Walter Kaufmann found similar results.

The oil-drop experiment was great because it not only helped find the basic unit of charge accurately, but it also showed that charge comes in specific, tiny packets. It's not a smooth, continuous thing. A scientist named Charles Steinmetz from General Electric used to think charge was continuous. But after working with Millikan's equipment, he changed his mind.

Understanding the Photoelectric Effect

When Albert Einstein published his important paper in 1905 about light being made of particles, Millikan thought it must be wrong. This was because there was so much evidence showing that light acted like a wave. So, he spent ten years doing experiments to test Einstein's idea. He even built a special "machine shop in vacuo" (meaning in a vacuum) to prepare very clean metal surfaces for his experiments.

His results, published in 1914, completely agreed with Einstein's predictions. However, Millikan still didn't fully believe Einstein's explanation. As late as 1916, he wrote that Einstein's photoelectric equation "cannot in my judgment be looked upon at present as resting upon any sort of a satisfactory theoretical foundation," even though it "actually represents very accurately the behavior" of the photoelectric effect. But in his autobiography in 1950, he simply said his work "scarcely permits of any other interpretation than that which Einstein had originally suggested," meaning the idea that light is made of tiny packets called photons.

It's interesting that Millikan's work helped create modern particle physics, but he was quite traditional in his views on new physics ideas. For example, his textbook, even in 1927, clearly stated that the ether existed. He only mentioned Einstein's theory of relativity in a small note at the end of a picture caption.

Millikan is also known for measuring the value of Planck's constant. He did this by using graphs from his photoelectric emission experiments with different metals.

Later Years and Legacy

In 1917, an astronomer named George Ellery Hale convinced Millikan to spend part of each year at Throop College of Technology in Pasadena, California. Hale wanted to turn this small school into a major science research center. A few years later, Throop College became the California Institute of Technology (Caltech). Millikan left the University of Chicago to become Caltech's "chairman of the executive council," which was like being its president. He held this position from 1921 to 1945.

At Caltech, most of his science research focused on "cosmic rays" (a term he created). In the 1930s, he had a debate with Arthur Compton. Millikan thought cosmic rays were high-energy photons (light particles). Compton believed they were charged particles. Compton was later proven right when scientists saw that cosmic rays were bent by Earth's magnetic field, meaning they must be charged particles.

Robert Millikan was also Vice Chairman of the United States National Research Council during World War I. He helped develop tools to find submarines and improve weather forecasting. After the war, Millikan worked with the League of Nations' International Committee on Intellectual Cooperation. He was part of this group from 1922 to 1931, along with other famous scientists like Marie Curie, Albert Einstein, and Hendrik Lorentz.

Millikan was on the planning committee for the 1932 Los Angeles Olympics. In his free time, he loved playing tennis. He was married and had three sons. His oldest son, Clark B. Millikan, became a well-known aerodynamic engineer. Another son, Glenn, was also a physicist. Glenn died in a climbing accident in 1947.

Millikan was a religious man and the son of a minister. Later in his life, he strongly believed that Christian faith and science could work together. He discussed this in his lectures at Yale in 1926–27. These talks were published as Evolution in Science and Religion. He believed in theistic evolution, which means he thought God guided the process of evolution.

Millikan was also involved with a group called the Human Betterment Foundation. Because of this connection, in January 2021, Caltech decided to remove Millikan's name from campus buildings.

Westinghouse Time Capsule

In 1938, Robert Millikan wrote a short message to be placed in the Westinghouse Time Capsules. These capsules were buried to be opened far in the future.

Death and Remembrance

Millikan died from a heart attack at his home in San Marino, California, in 1953. He was 85 years old. He was buried in the "Court of Honor" at Forest Lawn Memorial Park Cemetery in Glendale, California.

On January 26, 1982, the United States Postal Service honored him with a 37¢ postage stamp as part of their Great Americans series.

Tektronix named a street on their campus in Portland, Oregon, after Millikan. The Millikan Way (MAX station) for Portland's MAX Blue Line is also named after this street.

Name Changes on College Campuses

In the mid to late 1900s, many colleges named buildings, awards, and professorships after Robert Millikan.

In 1958, Pomona College named a science building Millikan Laboratory. However, after looking into Millikan's past connections, the college decided in October 2020 to rename the building. It is now called the Ms. Mary Estella Seaver and Mr. Carlton Seaver Laboratory.

At Caltech, several parts of the campus, rooms, awards, and a professorship were named after Millikan. The most famous was the Millikan Library, built in 1966. In January 2021, the Caltech Board of Trustees voted to remove Millikan's name from the campus. The Robert A. Millikan Library is now called Caltech Hall. In November 2021, the Robert A. Millikan Professorship was renamed the Judge Shirley Hufstedler Professorship.

Name Changes at Schools

In November 2020, Millikan Middle School in Los Angeles began the process of changing its name. In February 2022, the Los Angeles Unified School District voted to rename the school after musician Louis Armstrong.

In August 2020, the Long Beach Unified School District also started looking into renaming their Robert A. Millikan High School. As of early 2023, Long Beach is the only city that still has a school named after Millikan.

Name Removal from Awards

In the spring of 2021, the American Association of Physics Teachers voted to remove Millikan's name from the Robert A. Millikan award. This award honored "notable and intellectually creative contributions to the teaching of physics." A few months later, the award was renamed in honor of University of Washington physics professor Lillian C. McDermott.

Personal Life

In 1902, Robert Millikan married Greta Ervin Blanchard (1876-1955). They had three sons: Clark Blanchard, Glenn Allan, and Max Franklin.

Famous Sayings

"No more earnest seekers after truth, no intellectuals of more penetrating vision can be found anywhere at any time than these, and yet every one of them has been a devout and professed follower of religion."

See also

In Spanish: Robert Andrews Millikan para niños

In Spanish: Robert Andrews Millikan para niños

- Nobel Prize controversies

- Some people believe Robert Millikan was not given the Nobel Prize in 1920 because of claims by Felix Ehrenhaft. Ehrenhaft said he had measured charges smaller than Millikan's basic electron charge. Ehrenhaft's claims were later found to be incorrect, and Millikan received the prize in 1923.

- Millikan's passage about the new field of physics called quantum theory, published in Popular Science in January 1927.