1953 American Karakoram expedition facts for kids

The 1953 American Karakoram expedition was a brave mountain climbing trip to K2, the second highest mountain in the world. K2 is 8,611 meters (about 28,251 feet) tall. This was the fifth time anyone had tried to climb K2, and the first time since World War II.

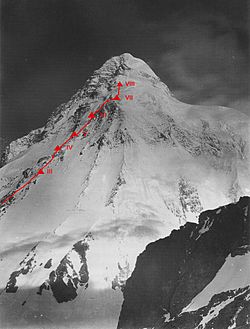

The team was mostly American and led by Charles Houston. They tried to climb the mountain's South-East Spur, also called the Abruzzi Spur. They used a very light climbing style, which was unusual for that time. The climbers reached a high point of 7,750 meters (about 25,426 feet).

However, a big storm trapped them in their high camp. A team member, Art Gilkey, became very sick. A difficult and dangerous trip down the mountain followed. During this retreat, almost all the climbers nearly fell to their deaths. Pete Schoening bravely stopped their fall. Sadly, Gilkey later died in what seemed to be an avalanche.

People have highly praised this expedition. They admire the climbers' courage in trying to save Gilkey. They also praise the strong team spirit and friendships that grew during the trip.

Contents

K2's Past Challenges

By 1953, four groups had already tried to climb K2. Early expeditions in 1902 and 1909 didn't get very far. The Duke of the Abruzzi even said K2 could never be climbed after his attempt.

However, two American expeditions in 1938 and 1939 got much closer. Charles Houston's 1938 trip showed that the Abruzzi Spur was a good path to the top. They reached 8,000 meters (about 26,247 feet) before turning back due to low supplies and bad weather.

Fritz Wiessner's attempt in 1939 went even higher. But it ended sadly when four men disappeared high on the mountain. Despite this tragedy, these trips proved that climbing K2 was possible. More attempts would have happened sooner, but World War II and the Indo-Pakistani War of 1947 made travel to Kashmir impossible.

Planning the Adventure

Even with travel problems, Charles Houston and Robert Bates hoped to return to K2. They had first tried in 1938. In 1952, Houston got permission for another expedition the next year. His friend, Avra M. Warren, the U.S. Ambassador to Pakistan, helped him.

Houston and Bates planned a "lightweight" expedition. This meant carrying less gear and fewer people. This style is now called Alpine style. There were good reasons for this choice. After India and Pakistan separated, Indian Sherpas (who usually helped carry gear) were not welcome in Pakistan. The local Hunza porters who replaced them were not as skilled in mountain climbing.

The Abruzzi Spur was very steep. It was hard to use porters to carry heavy loads high up. So, they planned to use porters only up to Camp II. Also, there wasn't much flat space for many tents on the steep mountain. Houston and Bates decided on a small team of eight climbers with no high-altitude porters.

A small team meant they couldn't carry extra oxygen tanks. But Houston believed they could climb K2 without it. He had done his own tests during the war. British expeditions to Mount Everest before the war also showed it was possible.

Houston and Bates picked climbers carefully. They looked for people who would work well together and had good all-around experience. Houston knew that arguments between climbers had caused problems on other trips. He wanted to avoid that.

The six climbers chosen were:

- Robert Craig, a ski instructor.

- Art Gilkey, a geologist.

- Dee Molenaar, a geologist and artist.

- Pete Schoening, the youngest at 25.

- George Bell, a nuclear scientist.

- Tony Streather, an English army officer. Tony started as the transport officer but became a full climber.

Some other skilled climbers were not chosen. This was because Houston felt they might not get along with the rest of the team.

The expedition paid for itself. It did not get money from the government or climbing groups. The $32,000 budget came from the team members, some gifts, and money from the National Broadcasting Company and the The Saturday Evening Post for a film and newspaper articles. They also took out big loans. Some companies gave them equipment and food instead of money.

Climbing, Storm, and Sickness

The team met in Rawalpindi in late May. They flew to Skardu and then hiked a long way through Askole and up the Baltoro Glacier. They arrived at the base of K2 on June 20.

The first parts of the climb went smoothly. They moved slowly because of their plan. Tragedies on other mountains had taught Houston a lesson. He believed it was important to keep all camps well-stocked. This way, if bad weather hit, they could retreat safely. This meant climbers made extra trips carrying supplies up and down the mountain. This choice would later help them survive.

By August 1, they had set up Camp VIII. This camp was at the base of the Shoulder, around 7,800 meters (about 25,590 feet). The next day, the whole team gathered there. They were ready for the final push to the summit.

But the weather had been getting worse for days. Soon, a severe storm began. At first, the team was not discouraged. They even held a secret ballot to decide who would try for the summit first. However, as the storm continued day after day, their situation became more serious. One tent collapsed on the fourth night. Houston and Bell had to squeeze into other already crowded tents. On August 6, with no hope for better weather, the team talked about going back down for the first time.

The next day, the weather improved a little. But thoughts of reaching the summit quickly disappeared. Art Gilkey collapsed just outside his tent. Houston realized Gilkey had thrombophlebitis. This meant he had blood clots. These are dangerous even at sea level, but almost certainly deadly at 7,800 meters.

The whole team now had to try desperately to save him. They knew there was little chance of saving him. But they never even thought about leaving him behind. However, the risk of avalanches was too high. Then the storm returned. This stopped them from going down right away. The team stayed at Camp VIII for several more days, hoping the weather would get better.

The Rescue Attempt and a Brave Act

By August 10, the situation was very serious. Gilkey was getting worse quickly. The whole team was still stuck at a height that could eventually kill them all. Even with the storm and avalanche risk, the team immediately started going down.

They made a simple stretcher from canvas, ropes, and a sleeping bag. They pulled or lowered Gilkey down steep parts of the mountain. They reached a point where they could cross a difficult ice slope to Camp VII. This camp was around 7,500 meters (about 24,600 feet).

As the climbers started to cross the ice slope, a big fall happened. George Bell slipped on some hard ice. He pulled his rope-mate, Tony Streather, with him. As they fell, their rope got tangled with the ropes connecting Houston, Bates, Gilkey, and Molenaar. This pulled all of them off the slope too.

Finally, the strain came onto Pete Schoening. He had been belaying (holding the rope for safety) Gilkey and Molenaar. Quickly, Schoening wrapped the rope around his shoulders and ice axe. He held all six climbers! He stopped them from falling into the Godwin-Austen Glacier. This amazing act became known simply as "The Belay."

After the climbers recovered and reached the tent at Camp VII, Gilkey was lost. He had been tied to the ice slope while the tired climbers set up the tent. They heard his muffled shouts. When Bates and Streather went back to get him, they found no sign of him. A faint mark in the snow suggested an avalanche had happened.

Some writers, like Jim Curran, have suggested that Gilkey's death, though sad, likely saved the lives of the others. They were now free to focus on their own survival. Houston agreed with this idea. But Pete Schoening always believed they could have saved Gilkey. He thought they might have gotten more frostbite, but they could have done it.

There is also some debate about how Gilkey died. Tom Hornbein and others have suggested that Gilkey might have untied himself. He might have realized his rescue was putting the others in danger. Charles Houston first thought Gilkey was too weak to untie himself. But in a 2003 documentary, he changed his mind. He then believed Gilkey had indeed untied himself. Other people, like Robert Bates, remained sure that an avalanche swept Gilkey away.

The trip down from Camp VII to Base Camp took five more days. It was very hard. All the climbers were exhausted. George Bell had badly frostbitten feet. Charles Houston had a head injury and was dazed and concussed. Houston has said he is proud of their attempt to rescue Gilkey. But he feels getting down safely was an even bigger achievement. During the descent, the climbers saw a broken ice-axe. But no other trace of Art Gilkey was found.

At Base Camp, the team built a memorial cairn (a pile of stones) for Art Gilkey. They also held a service. The Gilkey Memorial has since become a burial place for other climbers who have died on K2. It is also a memorial for those who have not been found.

In 1993, clothing and human remains were found near K2 Base Camp. These were confirmed to be Gilkey's. A British climber named Roger Payne led that expedition.

What Happened Next

Even after the difficult experience, Charles Houston wanted to try K2 again. He asked for permission for another trip in 1954. He was very disappointed that a large Italian expedition had already booked the mountain for that year.

The Italian expedition was successful. Houston had permission for 1955, but he didn't use it. He stopped mountain climbing to focus on his work researching high-altitude medicine.

Pete Schoening, however, returned to the Karakoram in 1958. With Andy Kauffman, he made the first climb of Gasherbrum I. At 8,080 meters (about 26,509 feet), this was the highest first ascent ever made by an American team.

Bates and Houston wrote a book about the expedition in 1954. It was called K2 - The Savage Mountain. Other climbers added sections too. The book was highly praised and is still a classic in mountain climbing stories.

Many K2 expeditions have ended with arguments and bad feelings. Examples include Wiessner's 1939 trip and the successful Italian expedition of 1954. But the 1953 expedition created strong, lifelong friendships among its members.

Houston said, "we entered the mountain as strangers, but we left it as brothers." Bates later added that "the Brotherhood of the Rope established on K2 outlasted the expedition by many decades." He said it was based on shared values, interests, and respect.

Because of this strong bond and the bravery shown in trying to save Art Gilkey, writers like Jim Curran call the expedition "a symbol of all that is best in mountaineering." Jim Wickwire, who made the first American climb of K2 in 1978, called their courage "one of the greatest mountaineering stories of all time." He wrote to Houston that being on the 1953 expedition would have been even better than climbing K2 in 1978.

Many years later, Reinhold Messner said he respected the Italian team that first climbed K2. But he respected the American team even more. He said that even though they failed, "they failed in the most beautiful way you can imagine." Messner was the first person to climb all fourteen 8,000-meter peaks.

In 1981, the American Alpine Club created the David A. Sowles Memorial Award. This award is for climbers who show great selflessness and risk their own safety to help others in the mountains. The surviving members of the 1953 expedition were among the first to receive this award.

Schoening's action of stopping the mass fall is very famous. In American climbing, it's simply known as "The Belay." Schoening himself was always humble about it. He claimed he was just lucky.

See also

In Spanish: Expedición americana al K2 de 1953 para niños

In Spanish: Expedición americana al K2 de 1953 para niños

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |