Cluny Abbey facts for kids

Cluny Abbey in 2004

|

|

| Monastery information | |

|---|---|

| Order | Benedictine |

| Established | 910 |

| Disestablished | 1790 |

| Dedicated to | Saint Peter and Saint Paul |

| Diocese | Autun |

| People | |

| Founder(s) | William I, Duke of Aquitaine |

| Site | |

| Location | Cluny, Saône-et-Loire, France |

| Coordinates | 46°26′03″N 4°39′33″E / 46.43417°N 4.65917°E |

Cluny Abbey (pronounced "kloo-NEE") was a very important Benedictine monastery in Cluny, France. It was dedicated to Saints Peter and Paul.

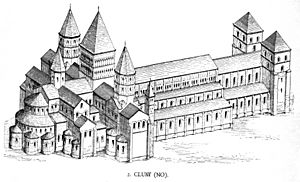

This abbey was built in the Romanesque architectural style. Three churches were built there over time, from the 4th to the early 12th centuries. The biggest one was the largest church in the world for a long time. It held this record until St. Peter's Basilica started being built in Rome.

Duke William I of Aquitaine founded Cluny Abbey in the year 910. He chose Berno to be its first abbot (the head of the monastery). The abbey was special because it followed the Rule of St. Benedict very strictly. This made Cluny a leader in western monasticism (the way monks live). Sadly, during the French Revolution in 1790, the abbey was attacked and mostly destroyed. Only a small part of it survived.

Since 1843, a building in Paris called the Hôtel de Cluny has been a public museum. This building used to be a townhouse for the abbots of Cluny. Today, it doesn't have anything from the original Cluny Abbey, except for its name and the building itself.

Contents

History of Cluny Abbey

How Cluny Abbey Started

In 910, William I, Duke of Aquitaine, also known as "the Pious," founded Cluny Abbey. He started it as a small Benedictine monastery. William gave the abbey many things, like vineyards, fields, woods, and mills. He also said that the abbey should welcome the poor, strangers, and travelers.

William made sure the monastery would be free from local rulers or church leaders. It would only answer to the Pope. He also said that no one, not even the Pope, could take its property or choose an abbot without the monks' permission. William put Cluny under the protection of Saints Peter and Paul. He even put a curse on anyone who tried to break these rules! Since the Pope was far away in Italy, this meant the monastery was mostly independent.

By giving his hunting land in Burgundy, William freed Cluny Abbey from any future duties to him or his family, except for prayers. Usually, people who founded monasteries expected to keep some control. But William wanted Cluny to be free from such worldly problems. This helped start the Cluniac Reforms, which were changes to how monasteries were run.

Soon, Cluny started getting gifts from all over Europe. It grew into a powerful group of monasteries and priories (smaller monasteries) that were all controlled by the main abbey at Cluny. This was a very new and successful system. The Abbots of Cluny became important leaders in Europe. Cluny was seen as the grandest and richest monastery. Its influence was strongest from the late 900s to the early 1100s.

Cluny and Church Reforms

The changes made at Cluny were partly inspired by Benedict of Aniane. He had shared his ideas at a big meeting of abbots in 817. Cluny was not known for being super strict or harsh. However, its abbots strongly supported the Pope and the reforms of Pope Gregory VII. Cluny became very closely linked with the Pope.

In the early 1100s, the order faced problems due to poor leadership. But it was brought back to life by Abbot Peter the Venerable (who died in 1156). He made sure that the smaller monasteries followed the rules again. Under Peter, Cluny reached its peak of power. Its monks became important church leaders like bishops and cardinals across France and the Holy Roman Empire.

However, by the time Peter died, newer and stricter orders, like the Cistercians, were starting to lead the next wave of church reforms. Also, countries like England and France were becoming more nationalistic. This made it harder for monasteries to be ruled by a head in Burgundy. The Western Schism (a time when there were rival popes) from 1378 to 1409 also caused problems. It divided loyalties, as France supported one pope and England another. This affected the relationship between Cluny and its dependent houses.

By the time of the French Revolution, people hated the Catholic Church. This led to the closing of the order in France in 1790. The monastery at Cluny was almost completely destroyed in 1810. Later, it was sold and used as a stone quarry until 1823. Today, only a small part of the original monastery remains.

Modern digs at the Abbey started in 1927. Kenneth John Conant, an American historian from Harvard University, led these excavations until 1950.

How Cluny Abbey Was Organized

Cluny Abbey was different from other Benedictine monasteries in three main ways:

- Its unique organization structure.

- It was not allowed to hold land through feudal service (a system where land was given in exchange for loyalty or service).

- It focused mainly on liturgy (church services and rituals) as its main work.

Cluny created a very centralized way of governing, which was unusual for Benedictine monasteries. Most Benedictine monasteries were independent. But Cluny formed a large, connected order. The leaders of its smaller houses were like deputies of the Abbot of Cluny and reported to him. These Cluniac houses were called priories, not abbeys, because they were directly under the Abbot of Cluny. The heads of the priories met at Cluny once a year to discuss issues and report. Many other Benedictine monasteries looked to Cluny for guidance.

The Cluniac monasteries for nuns were not seen as very cost-effective. So, the Order did not focus on starting many new houses for women. Their presence was always limited.

Cluny's customs changed the idea of a Benedictine monastery. Before, monasteries were supposed to be self-sufficient through farming. Monks would do physical labor as well as pray. But Cluny's agreement to offer constant prayer (called laus perennis, meaning "perpetual praise") meant that monks focused more on prayer.

As one of the richest monasteries in the Western world, Cluny hired managers and workers to do the traditional labor. The Cluniac monks spent almost all their time praying. This made prayer their main job. Even though monks were supposed to live simply, Cluny Abbey had candelabras made of solid silver and gold chalices with precious gems for its Masses. Instead of simple food, the monks ate very well. They enjoyed roasted chickens, wines from their vineyards, and cheeses made by their workers. The monks wore fine linen religious habits and silk vestments during Mass. Some of these rich items from Cluny Abbey are now shown at the Musée de Cluny in Paris.

Cluniac Prayer

O God, by whose grace thy servants, the Holy Abbots of Cluny, enkindled with the fire of thy love, became burning and shining lights in thy Church : Grant that we also may be aflame with the spirit of love and discipline, and may ever walk before thee as children of light; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who with thee, in the unity of the Holy Spirit, liveth and reigneth, one God, now and forever.

Cluniac Houses in Britain

Most of the English and Scottish Cluniac houses were called priories. This showed they were under Cluny's authority. The only exception was the priory at Paisley, which became an abbey in 1245 and answered only to the Pope. Cluny's influence reached Britain in the 11th century, starting at Lewes.

The head of their order was the Abbot at Cluny. All English and Scottish Cluniacs had to travel to Cluny in France to meet or be consulted. This was unless the abbot chose to come to Britain, which happened only a few times.

Arts and Architecture

At Cluny, the main activity was the liturgy (church services). These services were long and beautifully performed in inspiring buildings. This reflected a new feeling of deep religious devotion in the 11th century. People believed that monks' prayers were essential to reach a state of grace. Rulers competed to be remembered in Cluny's endless prayers. This led to gifts of land and money, which helped fund other arts.

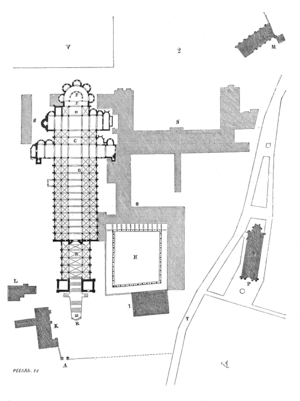

The fast-growing community at Cluny needed very large buildings. The designs at Cluny greatly influenced how buildings were made in Western Europe from the 900s to the 1100s. The three churches built one after another are called Cluny I, II, and III. The building of Cluny II, around 955–981, helped start the trend for churches in Burgundy to have stone-vaulted roofs.

Cluny III: A Giant Church

In 1088, Abbot Hugh of Semur (who was abbot since 1049) began building the third and final church at Cluny. This church became the largest church building in Europe. It remained the largest until the 1500s, when the current St. Peter's Basilica was built in Rome. Hézelon de Liège was the architect for this new church.

The building project was paid for by a yearly payment from Ferdinand I of León, a ruler in Spain. This was the largest yearly payment the Order ever received from a king or a common person. This money allowed Abbot Hugh to build the huge third abbey church. When these payments stopped later, the Cluniac order faced money problems.

The Cluny Library

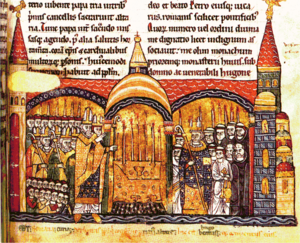

The library at Cluny was one of the richest and most important in France and Europe. It held many very valuable old books and writings. During religious conflicts in 1562, the Huguenots (French Protestants) attacked the abbey. They destroyed or scattered many of the manuscripts. Of those that were left, some were burned in 1790 by an angry crowd during the French Revolution. Others were stored in the Cluny town hall.

The French Government worked to find these treasures, including those that ended up in private hands. They are now kept at the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris. The British Museum also holds about sixty old documents from Cluny.

Important Burials at Cluny

Cluny's Wide Influence

Cluny Abbey was the main monastery of the Cluny group. In the scattered and local Europe of the 900s and 1000s, Cluny's reforming ideas spread far and wide. It was free from local rulers and bishops, and only answered to the Pope. This helped Cluny bring new life to the church in Normandy, reorganize the royal French monastery at Fleury, and inspire St Dunstan in England.

The first official English Cluniac priory was Lewes in Sussex, founded around 1077. The best-preserved Cluniac houses in England are Castle Acre Priory and Wenlock Priory. It is thought there were only three Cluniac nunneries in England, including Delapré Abbey.

Until the time of Henry VI, all Cluniac houses in England were French. They were governed by French priors and directly controlled from Cluny. Henry's decision to make the English priories independent abbeys was a political move. It showed England's growing sense of national identity.

By the 1100s, Cluniac religious devotion had spread throughout society. This was a time when the heart of Europe became fully Christian. By the 12th century, there were 314 monasteries across Europe that followed Cluny.

Well-born and educated Cluniac priors worked closely with local royal and noble supporters of their houses. They held important positions and were appointed as bishops. Cluny helped spread the idea of honoring the king as a supporter of the Church. In turn, the behavior and spiritual views of 11th-century kings seemed to change. In England, Edward the Confessor was later made a saint.

Cluny's very organized system was a training ground for Catholic leaders. Four monks from Cluny became popes: Gregory VII, Urban II, Paschal II, and Urban V.

A series of skilled and educated abbots, from the highest noble families, led Cluny. The first six abbots of Cluny were all made saints:

- St. Berno of Cluny (died 927)

- St. Odo of Cluny (died 942)

- St. Aymard of Cluny (died 965)

- St. Majolus of Cluny (died 994)

- St. Odilo (died 1049)

- St. Hugh of Cluny (died 1109)

Odilo continued to reform other monasteries. As Abbot of Cluny, he also kept tighter control over the order's many priories.

Decline and Destruction

Starting in the 12th century, Cluny faced serious money problems. This was mainly because of the high cost of building the third abbey (Cluny III). Also, the charity given to the poor increased its spending. As other religious orders like the Cistercians and then the Mendicants grew, Cluny's status and influence slowly weakened. Poor management of the abbey's lands and the unwillingness of its smaller priories to pay their share also reduced Cluny's income.

To deal with these issues, Cluny took out loans against its property, which put the order in debt. Throughout the late Middle Ages, conflicts with its priories increased. This fading influence happened as the Pope's power within the Catholic Church grew. By the early 1300s, the pope often chose Cluny's abbots.

Even though the monks (who were never more than 60) lived in luxury during this time, the wars of the 16th century further weakened the abbey. For example, in 1516, the king of France, Francis I, gained the power to appoint the abbot of Cluny.

Over the next 250 years, the abbey never got back its power or position. It was seen as an example of the problems of the old system in France. So, during the French Revolution, the monastic buildings and most of the church were destroyed. Its huge library and archives were burned in 1793. The church was looted. The abbey's property was sold in 1798. Over the next twenty years, the abbey's huge walls were used as a quarry for stone to rebuild the town.

Even though it was the largest church in Christendom until the 1600s, very little of the original buildings remain. Only about 10% of the original Cluny III floor space is left. This includes the southern transept (a part of the church) and its bell-tower, and the lower parts of two western towers. In 1928, the site was dug up by American archaeologist Kenneth John Conant. The ruined bases of columns still show how huge the church and monastery once were.

Since 1901, the site has been a center for the École nationale supérieure d'arts et métiers (ENSAM), which is a top engineering school.

See also

In Spanish: Abadía de Cluny para niños

In Spanish: Abadía de Cluny para niños

- Abbot of Cluny

- Basilica of Paray-le-Monial

- Berno of Cluny