Agriculture in the prehistoric Southwestern United States facts for kids

The way Native Americans farmed in the Southwestern United States was greatly shaped by how little rain the area gets. This region includes states like Arizona and New Mexico, plus parts of nearby states and Mexico. To grow food successfully, they needed to use Irrigation and clever ways of collecting and saving water.

To make the most of the limited water, people in the Southwest used irrigation canals, terraces (called trincheras), rock mulches, and farmed in floodplains. Being good at farming allowed some Native Americans to live in large communities, sometimes with as many as 40,000 people. Before this, they lived as hunter-gatherers in small groups of only a few dozen.

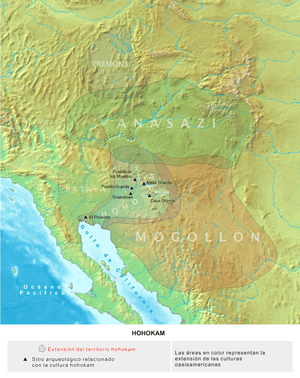

Maize (corn) was the most important crop. It came from Mesoamerica and was grown in the Southwest U.S. by at least 2100 BCE. After farming became common, groups like the Hohokam, Mogollon, Ancestral Puebloans, and Patayan settled down and built communities.

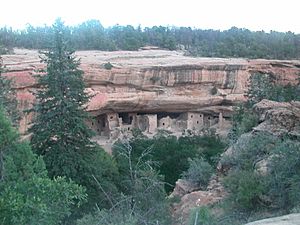

Farming in the Southwest was tough because of the environment. Many successful farming societies eventually disappeared or changed. However, they left behind amazing archaeological sites that show how they lived. Some farming cultures, like the Pueblos in the U.S. and the Yaqui and Mayo in Mexico, were very strong and still exist today.

Contents

First Farmers

Native Americans might have grown some local plants like gourds and chenopods very early on. But the first clear sign of maize farming in the Southwest is from about 2100 BCE. Small, old corn cobs have been found at five different places in New Mexico and Arizona.

These sites are in very different climates. Some are in the desert near Tucson, which is about 700 meters (2,300 feet) high. Others are in a rocky cave on the Colorado plateau, about 2,200 meters (7,200 feet) high. This shows that the early corn they grew could already handle both hot, dry weather and places with short growing seasons.

Corn arrived in the Southwest from Mexico, but we don't know the exact path. It spread quite quickly. One idea is that farmers who spoke a Uto-Aztecan language brought corn north from central Mexico. Another idea, which many experts now believe, is that corn seeds were passed from one group to another, rather than by migrating farmers.

The first time corn was grown in the Southwest was during a time when there was more rain. Even though corn farming spread fast, the hunter-gatherers living there didn't immediately rely on it as their main food. Instead, they added corn farming as a small part of their food-finding methods. Hunter-gatherers usually eat many different foods to be safe if one food source fails.

Before farming, hunter-gatherer groups were usually small, with only 10 to 50 people. Sometimes, several groups would meet for ceremonies or to help each other. As corn farming became more important, communities grew larger and stayed in one place. However, hunting and gathering wild foods were still important.

Some farming towns in the Southwest, like Casa Grande and Casas Grandes, along with Pueblo and Opata settlements, might have had over 2,000 people at their busiest times. Many more people lived in smaller towns of 200 to 300 people, or in isolated homes. Corn farming started in the Southwest many centuries before it began in the eastern United States, even though the eastern U.S. has much better farming weather.

Crops Grown

Early farmers in the Southwest likely started by helping wild grains like Amaranth and chenopods grow. They also grew gourds for their edible seeds and to use as containers. The oldest corn found in the Southwest was a type of popcorn with a cob only about one or two inches long. It didn't produce much food.

Over time, farmers in the Southwest developed better types of corn, or new ones were brought from Mesoamerica. Beans and squash also came from Mesoamerica. However, the Tepary bean, which can handle dry weather, was native to the area.

Cotton, which was probably grown on farms, has been found at ancient sites from about 1200 BC in the Tucson basin. There's also proof of tobacco use, and possibly farming, around the same time. Agave, especially a type called Agave murpheyi, was a major food for the Hohokam. They grew it on dry hillsides where other crops wouldn't grow. Early farmers also ate and possibly helped grow cactus fruit, mesquite beans, and wild grasses for their seeds.

Farming Tools

Native Americans in the Southwest did not have animals to help them farm, nor did they have metal tools. They planted seeds using a sharpened stick, hardened by fire, which is now called a dibble stick. Hoes and shovels were made from wood and the shoulder bones of large animals like buffalo. They also used mussel shells, pottery pieces, and rocks as tools for planting and digging.

Farmers did not usually add fertilizer to their fields using animal waste. Instead, they rotated their crops, left fields empty for a while to let the soil recover, and relied on silt (fine dirt) left behind by rainwater. Sometimes, they used fire to clear land and add ash to the soil as fertilizer. They carried water in large pottery jugs to water small garden plots by hand.

Water Management

Farming in the lower parts of the Southwest is very hard without irrigation because there isn't much rain, and it's unpredictable. Higher up, around 1,500 meters (5,000 feet), there might be more rain, but it's also colder, has shorter growing seasons, and the soil isn't as rich. In both cases, farming was a big challenge.

Ancient farmers in the Southwest used many strategies to grow food. These included choosing the best seeds, letting fields rest, planting in different places, planting at different times, and growing separate types of corn and beans.

Canal Irrigation

The Las Capas site near Tucson has the oldest irrigation system found in North America, dating back to 1200 BCE. This system of canals and small fields, each about 23 square meters (250 square feet), covers more than 40 hectares (100 acres). This shows that a large community of people was organized enough to build such big public projects. Tobacco pipes, the oldest smoking pipes found so far, were also discovered here. This site might have supported 150 people. The corn grown at Las Capas was similar to today's popcorn. Archaeologists think the kernels were popped and then ground into flour to make tortillas.

The Las Capas people were likely the ancestors of the Hohokam, who were the most skilled farmers in the Southwest. The Hohokam lived in the Gila and Salt river valleys of Arizona between the first century and 1450 CE. Their society grew strong around 750 CE, probably because they were so good at farming.

The Hohokam built a huge system of canals to water thousands of acres of farmland. Their main canals were up to 10 meters (10 yards) wide, 4 meters (4 yards) deep, and stretched for as much as 30 kilometers (19 miles) across the river valleys. At the peak of their culture in the 14th century, the Hohokam might have had 40,000 people.

The sudden disappearance of the Hohokam between 1400 and 1450 CE is a mystery. Archaeologists guess that keeping the canals working was very hard, and dirt built up over centuries. Farmers had to leave old canals and move further from the river, which made farming even harder. After a thousand years of success, the Hohokam could no longer keep up their intense farming system. They vanished from the archaeological record. When Spanish explorers arrived in the Gila and Salt valleys in the 16th century, only a few Pima and Tohono O'odham (Papago) Indians lived there. These groups are likely the descendants of the Hohokam.

After the Hohokam disappeared, Spanish explorers in the 16th century saw canal irrigation being used in only two areas of the Southwest. One was eastern Sonora, mainly by the Opata and Lower Pima. The other was among the Pueblos of northern New Mexico.

The Opata and Pueblos used irrigation for different reasons. In Sonora, with a long growing season, they grew two corn crops a year in river valleys. The spring crop during the dry season needed irrigation. The summer and fall crop during the rainy season used irrigation to add to the rainfall. Needing irrigation probably meant they had a high level of social organization. In New Mexico, where only one corn crop per year was possible, irrigation was extra help. Less reliance on irrigation suggests less social organization than in Sonora.

Trincheras

Trincheras (Spanish for "trenches" or "fortifications") are rock walls or terraces built on hillsides by ancient Native Americans. Trincheras are found all over the Southwest. They date back to almost the very beginning of farming in the Southwest. By about 1300 BCE, at Casas Grandes in Chihuahua, early farmers built hilltop forts and trincheras on hillsides. These large projects needed a lot of work and organization, which means there was a settled and large community.

Trincheras had several uses, such as defense, places for homes, and farming. For farming, they gave farmers a flat surface to plant on and helped prevent soil from washing away. They also collected and managed water and protected plants from frost. Farming on hillsides in the small fields made by trincheras was often less important than farming in floodplains. Trincheras were probably used to grow all kinds of crops. Farmers in the Southwest often grew different crops in several fields in different places and environments. This helped reduce the risk of all their crops failing. If one or more plantings didn't work, other plantings might still succeed.

Four types of trincheras were built. Check dams were built across natural water paths to catch rainwater runoff. Terraces and linear borders were built along the natural curves of the land to create flat planting areas or home sites. Near permanent streams and rivers, riverside terraces were built to catch overflowing floodwater. Trincheras were very widespread. For example, archaeologists have found 183 upland farming spots near the site of Casas Grandes with trincheras that add up to 26,919 meters (almost 18 miles) in length. This wide use and importance of trincheras at Casas Grandes was also seen in many other farming societies in the Southwest.

Rock Mulch

Rock mulch was another farming method in the Southwest. Rocks or pebbles were used as a mulch around growing plants and in fields. The rocks acted like a cover to keep moisture in the soil, reduce soil erosion, control weeds, and make nighttime temperatures warmer. This happened because the rocks absorbed heat during the day and released it at night.

In the 1980s, archaeologists found that large areas of agave, especially Agave murpheyi, had been grown in rock mounds by the Hohokam in the Tucson Basin, near the city of Marana. Since then, 78 square kilometers (almost 20,000 acres) of old agave fields have been found, mostly between Phoenix and Tucson. Many other fields have surely been destroyed or haven't been found by archaeologists. Northern New Mexico also has the remains of many fields covered with rocks. Corn and cotton pollen have been found in the soil linked to these rock mounds and mulch.

Floodplain Farming

To make sure they had enough food, Native Americans in the Southwest farmed the floodplains of rivers and temporary streams. Crops were planted on floodplains and islands to use the high water when the river or stream overflowed. This soaked the land with water and made the soil richer with silt. This method worked best when floods happened at predictable times.

Floodplain farming was used instead of canal irrigation by the La Junta Indians (often called Jumano) along the Rio Grande in western Texas. Other groups also used this method.

The semi-nomadic Tohono O'odham and other Indians of the Sonora Desert practiced ak-chin farming of the native tepary bean (Phaseolus acutifolius). In this very dry desert, after summer monsoon rains, the Papago would quickly plant tepary beans in small areas where a stream or dry riverbed had overflowed and soaked the soil. The tepary bean grew fast and ripened before the soil dried out. The Indians often managed the flow of floodwater to help the beans grow.

Floodplain farming was possible even in the toughest conditions. The Sand Papago (Hia C-eḍ O'odham) were mainly hunter-gatherers, but they farmed in floodplains when they could. In 1912, a researcher named Carl Lumholtz found small cultivated fields, mostly of Tepary beans, in the Pinacate Peaks area of Sonora. In the Pinacate, which gets only about 75mm (3 inches) of rain a year and has temperatures up to 48°C (118°F), Papago and Mexican farmers used runoff from the scarce rains to grow crops.

In the 1980s, author Gary Paul Nabhan visited this area. He found one farm family taking advantage of the first big rain in six years. They planted seeds in the wet ground and harvested a crop two months later. The most successful crops were Tepary beans and a type of squash that could handle dry weather. Nabhan calculated that the Pinacate is the driest place in the world where farming is done only with rain.

What Happened to the Farmers?

The Southwest is full of ancient ruins from Native American societies that tried to overcome the harsh farming challenges in the region. The Ancestral Puebloan centers of Chaco Canyon and Mesa Verde were abandoned in the 12th and 13th centuries CE, probably because of long dry periods. After a thousand years of success, the complex Hohokam society disappeared in the 15th century CE and became the smaller-scale Pima culture we know from history.

However, many Native American farming societies have been incredibly strong and lasted a long time. The Rio Grande Pueblos, the Hopi, and the Zuni have survived to this day, keeping much of their traditional culture. Many Mexican Indians have blended into a mixed society, but the Yaqui and Mayo still keep their unique identities and part of their traditional lands. The once large Opata have disappeared as a distinct group, but their descendants still live in the valleys of the Sonora River and its smaller rivers.

|

See also

In Spanish: Agricultura en el suroeste de Estados Unidos prehistórico para niños

In Spanish: Agricultura en el suroeste de Estados Unidos prehistórico para niños