Akhenaten facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

|

|

|---|---|

| Amenophis IV, Naphurureya, Ikhnaton | |

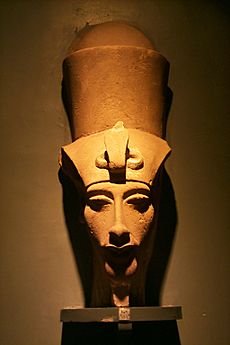

Statue of Akhenaten at the Egyptian Museum

|

|

| Pharaoh | |

| Reign |

|

| Predecessor | Amenhotep III |

| Successor | Smenkhkare |

| Consorts |

|

| Children |

|

| Father | Amenhotep III |

| Mother | Tiye |

| Died | 1336 or 1334 BC |

| Burial |

|

| Monuments | Akhetaten, Gempaaten |

| Religion | |

Akhenaten was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh who ruled from about 1353 to 1336 BC. He was the tenth ruler of the Eighteenth Dynasty. Before his fifth year as pharaoh, he was known as Amenhotep IV. His name Akhenaten means "Effective for the Aten".

Akhenaten is famous for changing Egypt's traditional religion. He moved away from worshipping many gods (polytheism) and focused on one god, the Aten. The Aten was shown as the sun disk. After Akhenaten died, his religious changes were reversed. His monuments were taken apart, and his name was removed from official lists of rulers. Later pharaohs even called him "the enemy."

Akhenaten was mostly forgotten until the late 1800s. That's when his new capital city, Amarna, was discovered. In 1907, a mummy believed to be Akhenaten's was found. Genetic tests show this mummy was Tutankhamun's father.

People today are fascinated by Akhenaten. This is because of his link to Tutankhamun, the unique art style from his time, and the new religion he tried to create.

Contents

Family Life

Akhenaten was born Prince Amenhotep. His parents were Pharaoh Amenhotep III and Queen Tiye. He had an older brother, Thutmose, who was supposed to be the next pharaoh. But Thutmose died young, making Akhenaten the next in line for the throne.

Akhenaten's main wife was Nefertiti. They likely married around the time he became pharaoh. He also had another wife named Kiya. Some historians think Kiya was the mother of Tutankhamun.

Akhenaten had six daughters: Meritaten, Meketaten, Ankhesenamun, Neferneferuaten Tasherit, Neferneferure, and Setepenre. Tutankhamun, who was first named Tutankhaten, was most likely Akhenaten's son.

Early Years as Prince

We don't know much about Akhenaten's early life as Prince Amenhotep. He was probably born around 1363–1361 BC. He might have grown up in Memphis, where the worship of the sun god Ra was important.

The only person we know for sure who served the prince was Parennefer. His tomb mentions this fact.

His Time as Pharaoh

Ruling with his Father

Historians disagree about whether Akhenaten ruled at the same time as his father, Amenhotep III. Some believe they ruled together for up to 12 years. Others think there was no shared rule, or only for a year or two.

In 2014, archaeologists found both pharaohs' names in a tomb in Luxor. This led some to believe they shared power for at least eight years. However, other experts say the inscription just means the tomb was started under one pharaoh and finished under the next.

Starting as Amenhotep IV

Akhenaten became pharaoh as Amenhotep IV, likely in 1353 or 1351 BC. He was probably crowned in Thebes.

At first, Amenhotep IV followed old traditions. He didn't immediately stop the worship of other gods. He even continued his father's building projects at Karnak. He decorated temples with images of himself worshipping Ra-Horakhty, a traditional sun god.

However, Amenhotep IV also started building new places to worship the Aten. He ordered temples for the Aten in several cities. A large temple complex for the Aten was built at Karnak. These new Aten temples had no roof, so people worshipped the god under the open sky.

Around his second or third year, Amenhotep IV held a Sed festival. This was a special ceremony to renew a pharaoh's power, usually held after 30 years of rule. It's unclear why he held it so early. Some think it was to honor the Aten or to show his rule continued his father's.

Changing His Name

Around his fifth year as pharaoh, Amenhotep IV changed his name to Akhenaten. This showed his strong devotion to the Aten. He no longer wanted to be linked to the god Amun, whose name was in "Amenhotep."

The name Akhenaten means "Effective for the Aten." It showed that he believed he was working directly for the sun disk god.

| Amenhotep IV | Akhenaten | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Horus name |

Kanakht-qai-Shuti "Strong Bull of the Double Plumes" |

Meryaten "Beloved of Aten" |

|||||||||||||||||||

| Nebty name |

Wer-nesut-em-Ipet-swt "Great of Kingship in Karnak" |

Wer-nesut-em-Akhetaten "Great of Kingship in Akhet-Aten" |

|||||||||||||||||||

| Golden Horus name |

Wetjes-khau-em-Iunu-Shemay "Crowned in Heliopolis of the South" (Thebes) |

Wetjes-ren-en-Aten "Exalter of the Name of Aten" |

|||||||||||||||||||

| Prenomen |

Neferkheperure-waenre "Beautiful are the Forms of Re, the Unique one of Re" |

||||||||||||||||||||

| Nomen |

Amenhotep Netjer-Heqa-Waset "Amun is Satisfied, Divine Lord of Thebes" |

Akhenaten "Effective for the Aten" |

|||||||||||||||||||

Building Amarna

Around the same time he changed his name, Akhenaten decided to build a new capital city. He called it Akhetaten, meaning "Horizon of the Aten." Today, it's known as Amarna.

Akhenaten chose a spot between Thebes and Memphis, on the east bank of the Nile. The area had never been lived in before. He said the land didn't belong to any god or ruler, making it perfect for Aten's city.

Historians aren't sure why Akhenaten left Thebes, the old capital. The boundary markers of Akhetaten hint at "offensive" speech against the Aten. This suggests Akhenaten might have had conflicts with the priests of Amun, the main god of Thebes. Moving to a new capital could have been a way to break away from their power.

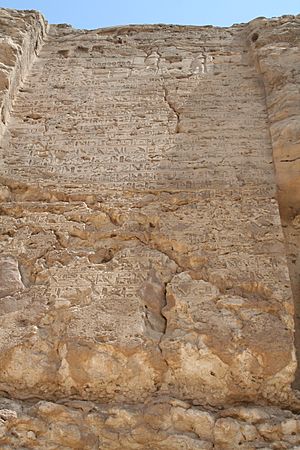

Akhetaten was a planned city. It had large temples for the Aten, royal homes, and government buildings. The city was built very quickly. Builders used smaller, standardized blocks called talatats. These were easier and faster to use than the huge blocks from earlier times.

By his eighth year as pharaoh, Akhetaten was ready for the royal family. Only Akhenaten's most loyal followers moved to the new city. Building work in Thebes stopped, but continued in other parts of Egypt, with new Aten temples in cities like Heliopolis and Memphis.

Dealing with Other Countries

The Amarna letters are a collection of clay tablets. They show how Akhenaten handled foreign policy. These letters were messages between Egyptian pharaohs and rulers of other lands.

Before Akhenaten, Egypt was very powerful. But during his reign, the Hittites in Syria grew stronger. This changed the balance of power in the Middle East. Akhenaten seemed to prefer diplomacy over war.

Many letters from Egyptian allies asked Akhenaten for troops. For example, Rib-Hadda of Byblos sent 60 letters begging for help. His kingdom was under attack. Akhenaten often did not send large armies to help these small states. Rib-Hadda was eventually exiled and likely executed.

Some early historians thought Akhenaten was a pacifist. They believed he ignored foreign lands for his religious changes. But other historians disagree. They point out that Akhenaten did send troops when needed. He also kept control over Egypt's main territories in the Near East.

Only one military campaign is known for sure during Akhenaten's rule. In his second or twelfth year, he sent troops to stop a rebellion in Nubia. This victory was recorded on two stone markers.

Later Years

We know little about Akhenaten's last five years. In 2012, an inscription was found from his sixteenth year. It shows that Akhenaten and Nefertiti were still ruling together.

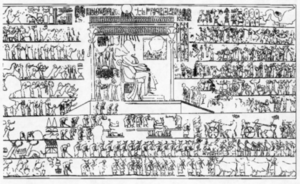

The last major event we know of was a royal reception in his twelfth year. Akhenaten and his family received gifts from allied countries. This was likely the peak of his reign.

Some historians think a plague hit Egypt around this time. This disease might have caused the deaths of some of Akhenaten's daughters.

Akhenaten might have ruled with Smenkhkare and Nefertiti before he died. Smenkhkare might have been his son or brother. He was married to Akhenaten's oldest daughter, Meritaten. Nefertiti might have become a co-ruler later on. Some believe these shared rules were to keep the family in power during the epidemic.

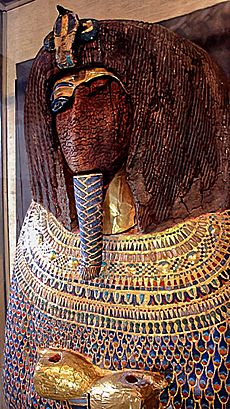

Akhenaten died after 17 years as pharaoh. He was first buried in a tomb in the Royal Wadi near Akhetaten. His sarcophagus was later destroyed. His mummy was moved to tomb KV55 in the Valley of the Kings. This tomb was later damaged.

The mummy found in KV55 is believed to be Akhenaten. However, its exact identity is still debated by experts.

What He Left Behind

After Akhenaten's death, his Aten religion slowly faded away. His immediate successors, like Smenkhkare and Neferneferuaten, and then Tutankhamun, continued some Aten worship at first.

But soon, Akhenaten's changes were reversed. Tutankhamun changed his name from Tutankhaten. He brought back the worship of Amun and other traditional gods. He rebuilt their temples.

Later pharaohs, like Horemheb and Seti I, tried to erase Akhenaten from history. They destroyed Aten temples and reused the blocks. Akhetaten, his capital city, was also destroyed. Akhenaten's reign was even called "the time of the enemy."

Akhenaten's rule also changed how Egyptians saw their pharaohs and gods. Before him, the pharaoh was seen as a living god. After him, people felt a more direct connection to the gods themselves. The god Amun became very powerful again.

Akhenaten's changes also affected the Egyptian language. More everyday words started appearing in official writings. Even though later pharaohs tried to undo his changes, these new language elements remained.

Atenism

Egyptians had worshipped sun gods for a long time. But Akhenaten took this worship to a new level.

How Atenism Grew

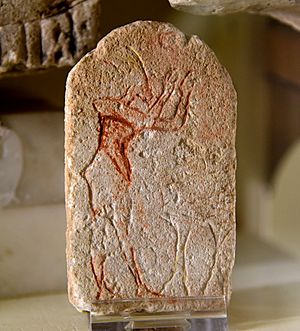

The worship of Aten changed over time. At first, the sun disk was shown with the traditional sun god Ra-Horakhty. Then, the Aten became more important than other gods. Its name was even put in cartouches, like a pharaoh's name.

Finally, the Aten was shown as a sun disk with rays ending in human hands. These hands offered life. A new title for the Aten was used: "the great living Disc which is in jubilee, lord of heaven and earth."

In his early years, Akhenaten allowed other gods to be worshipped. But he gave more importance to the Aten. He built temples for the Aten that were open to the sky, unlike the dark temples of other gods.

Around his second year, Akhenaten gave a speech. He said other gods were not working, but the Aten was eternal. This speech hinted at his future religious changes.

In his fifth year, Akhenaten made big changes. He stopped funding for other gods' priests. He used their money to support the Aten. He changed his name to Akhenaten to show his loyalty. The Aten itself was treated like a king, with royal symbols. Akhenaten declared himself the only one who could worship the Aten.

By his ninth year, Akhenaten said the Aten was the only god to be worshipped. He ordered the names of other gods, especially Amun, to be removed from temples. He banned images of gods, except for the rayed sun disk. The Aten was seen as a universal god, the creator of all life.

Akhenaten's beliefs are best seen in the Great Hymn to the Aten. This hymn praises the sun and daylight. It says the Aten is the only god and creator of all life. It also states that Akhenaten is the only person who truly understands the Aten.

Atenism and Other Gods

Historians debate how much Akhenaten forced his new religion. He did remove references to other gods. Many people in Amarna removed Amun's name from their personal items. This might have been out of fear.

However, some people in Amarna still kept names linked to other gods. Amulets of traditional gods were also worn. This suggests that Akhenaten's policies might have been more tolerant at first.

After Akhenaten

After Akhenaten died, Egypt slowly went back to worshipping many gods. The Aten cult faded. Tutankhamun changed his name and moved the capital back to Thebes. He restored the temples of the old gods.

Later pharaohs, like Horemheb and Seti I, continued to destroy Aten temples. They wanted to erase Akhenaten's religious changes.

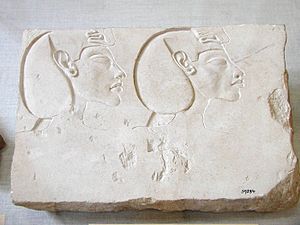

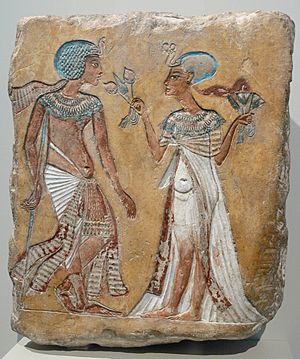

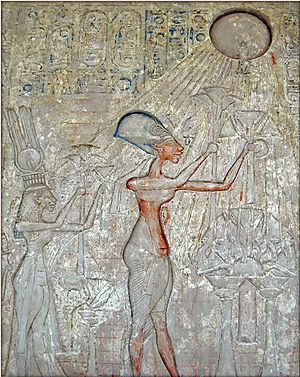

Art from Akhenaten's Time

The art style during Akhenaten's reign is called Amarna art. It was very different from traditional Egyptian art. It was more realistic and showed more movement.

Akhenaten's own portrayals were unusual. Instead of being shown as young and athletic, he was depicted with a sagging stomach, wide hips, and a long face.

Some people thought these unusual depictions meant Akhenaten had a medical condition. But most Egyptologists now believe it was a symbolic choice. The Aten was seen as both male and female. So, Akhenaten might have been shown as androgynous to represent the Aten's qualities.

Art from this time also showed the royal family in new ways. They were seen in relaxed, everyday situations. They held hands and kissed, showing affection. This was very unusual for royal art.

Queen Nefertiti also appeared in art in ways usually reserved for pharaohs. This suggests she had a very important role.

Interesting Ideas About Akhenaten

Akhenaten's religious changes have led to many theories. Some believe his religion was truly monotheistic (worshipping only one god). Others think it was monolatry (worshipping one god, but not denying others exist).

Akhenaten and Monotheism

Some scholars have wondered if Akhenaten's religion influenced later monotheistic faiths like Judaism. For example, Sigmund Freud suggested that Moses might have been an Atenist priest. There are also similarities between Akhenaten's Great Hymn to the Aten and Psalm 104 in the Bible.

Some have even compared Akhenaten's relationship with the Aten to Jesus Christ and God. Akhenaten called himself "Thine only son that came forth from thy body."

Possible Health Issues

Akhenaten's unusual appearance in art led some to think he had a genetic condition. Conditions like Marfan syndrome were suggested. However, DNA tests on Tutankhamun's mummy did not show signs of Marfan syndrome.

Most Egyptologists now believe his artistic portrayals were symbolic. They showed the qualities of the Aten god, rather than a real illness.

Akhenaten in Culture

Akhenaten has appeared in many books, movies, and games since his rediscovery. He is one of the most popular ancient figures in fiction.

In novels, he is often shown as a revolutionary pharaoh. These stories focus on his religious changes and his struggles with the Amun cult. Examples include Akhnaton King of Egypt by Dmitry Merezhkovsky and Akhenaten, Dweller in Truth by Naguib Mahfouz. He also appears in The Egyptian, which was made into a movie.

In the 21st century, Akhenaten has been a villain in comic books and video games. He is the main bad guy in the Marvel: The End comic series. He also appears as an enemy in the Assassin's Creed Origins video game.

The band Nile also has a song about Akhenaten called Cast Down the Heretic.

See Also

In Spanish: Akenatón para niños

In Spanish: Akenatón para niños

- Pharaoh of the Exodus

- Osarseph

Images for kids