Ambrosio José Gonzales facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

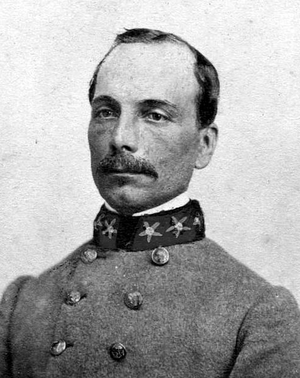

Ambrosio José Gonzales

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | October 3, 1818 Matanzas, Cuba |

| Died | July 31, 1893 (aged 74) The Bronx, New York |

| Place of burial |

Woodlawn Cemetery, Bronx, New York

*Plot: Lot A, Range 131, Grave 20 |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ |

|

| Years of service | 1861–1865 |

| Rank | |

| Commands held | Chief of Artillery, Department of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War *Battle of Fort Sumter *Battle of Honey Hill |

Ambrosio José Gonzales (born October 3, 1818 – died July 31, 1893) was a Cuban who wanted to free his home country. He became a general in the Cuban revolutionary movement. Later, he became a colonel in the Confederate Army during the American Civil War.

Gonzales believed that the United States should take over Cuba to help it become free from Spanish rule. During the American Civil War, he was in charge of artillery for the Confederate forces in South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Ambrosio José Gonzales was born in Matanzas, Cuba, in 1818. His father was a schoolmaster and started the first daily newspaper in Matanzas. His mother came from an important local family.

When Ambrosio was nine, his mother passed away. His father sent him to Europe and New York City for his early schooling. He later returned to Cuba and studied at the University of Havana. He earned degrees in arts, sciences, and law by 1839.

After graduating, Gonzales became a teacher. He taught languages at the University of Havana. He could speak English, French, Spanish, and Italian. He was also good at math and geography. In 1845, after his father died, he traveled for two years. He visited Europe and the United States before returning to his teaching job.

Fighting for Cuba's Freedom

In 1848, Gonzales joined a secret group called the Havana Club. This group wanted the United States to annex Cuba. Annexation meant Cuba would become part of the U.S. This was seen as a way to free the island from Spanish control. Many Americans, especially in the South, supported this idea. They had recently seen the U.S. annex Texas in 1845.

The Havana Club tried to achieve its goal using money, diplomacy, and military action. Gonzales used his connections with important Americans to write a statement. This statement encouraged the U.S. to annex Cuba.

By 1849, Gonzales became interested in the plans of Venezuelan General Narciso López. López led several military trips, called filibusters, to try and free Cuba from Spain. Gonzales joined López on some of these trips between 1849 and 1851.

The Spanish authorities tried to capture López. He managed to escape and found safety in the United States.

Becoming a U.S. Citizen

In 1849, Gonzales became a US citizen. This was possible under a law for free white people who had lived in the U.S. for at least three years before age 21. After this, a Cuban group asked him to get help from General William J. Worth. Worth was a U.S. veteran of the Mexican–American War.

Gonzales and Worth planned an expedition of 5,000 American soldiers. They would land in Cuba and help Cuban patriots led by López. But the plan did not happen because General Worth died unexpectedly.

López and Gonzales then organized another expedition called the Creole. They raised $40,000 by selling Cuban bonds. John A. Quitman, a former U.S. Army general, also helped fund the trip. López led the expedition, with Gonzales as his Chief of Staff.

On May 19, 1850, López ordered an attack. Gonzales and his men attacked the Governor's palace. The expedition failed because the Cuban people did not support them. Also, they were no match for the strong Spanish military.

Gonzales, López, and their men returned to the Creole. A Spanish warship chased them, so they sailed to Key West, Florida. Gonzales spent three weeks there recovering from his injuries.

On December 16, 1850, López, Gonzales, and others were tried in New Orleans. They were accused of breaking laws about neutrality. After three attempts to convict them, the case was dropped.

Life in South Carolina

After another failed expedition by López in 1851, Gonzales settled in Beaufort, South Carolina. He continued to seek help for Cuban independence. He met with U.S. leaders like President Franklin Pierce and Secretary of War Jefferson Davis.

In 1856, he married Harriet Rutledge Elliot. She was 16 years old and the daughter of William Elliott. William Elliott was an important South Carolina senator and writer. Ambrosio and Harriet had six children together:

- Ambrose E. Gonzales (1857–1926)

- Narciso Gener Gonzales (1858–1903)

- Alfonso Beauregard Gonzales (1861–1908)

- Gertrude Ruffini Gonzales (1864–1900)

- Benigno Gonzales (1866–1937)

- Anita Gonzales (1869–?)

Service in the American Civil War

As the secession of Southern states approached in the late 1850s, Gonzales became a sales agent. He sold firearms to state governments in the South. He demonstrated weapons like the LeMat revolver and Maynard Arms Company rifles.

When the American Civil War began, Gonzales joined the Confederate Army. He volunteered to serve on the staff of General Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard. Beauregard had been Gonzales's schoolmate in New York City.

Gonzales was active during the attack on Fort Sumter. General Beauregard praised his help in his official report:

Monday, May 6, 1861. Official Report of the Bombardment of Fort Sumter.

To my volunteer staff... I am indebted for their tireless and valuable assistance, night and day, during the attacks on Sumter, transmitting, in open boats, my orders when called upon, with eagerness and cheerfulness, to the different batteries, amidst falling balls and bursting shells...

I am, sirs, very respectfully,

Your obedient servant,

G. T. Beauregard,

Brigadier General Commanding

Gonzales also worked as a special aide to the governor of South Carolina. He created plans to defend the state's coastal areas. Major Danville Leadbetter wrote to the Secretary of War about Gonzales's ideas. He said Gonzales's plans for mobile artillery could be very useful for coastal defense.

Gonzales was then made a Lieutenant Colonel of artillery. He was put in charge of inspecting coastal defenses. In 1862, he was promoted to colonel. He became the Chief of Artillery for the Department of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida. This department was under General John C. Pemberton.

Gonzales was good at moving his heavy artillery. He placed his cannons on special carriages. This made them mobile and helped him stop Union gunboats. The gunboats were trying to destroy railroads and other important places on the Carolina coast.

On November 30, 1864, Gonzales was the artillery commander at the Battle of Honey Hill. This was a battle during Sherman's March to the Sea in Savannah, Georgia.

Confederate President Jefferson Davis turned down Gonzales's requests to be promoted to general six times. Davis did not like Beauregard, who was Gonzales's commander. Also, Davis thought Gonzales was not fit to command because of his past failed Cuban expeditions. He also had disagreements with other Confederate officers.

Later Years and Family

After the war, Gonzales tried many different jobs. None of them were very successful. Like many wealthy Southerners after the war, he struggled to get back his money and social standing.

In 1869, Gonzales and his family moved to Cuba. There, his wife, Harriet Elliott Gonzales, died from yellow fever. Gonzales returned to South Carolina with four of his children. Two children, Narciso and Alfonso, stayed in Cuba with friends for a year. By 1870, all the Gonzales children were back in the United States. Their grandmother and aunts raised them. Gonzales faced not only money problems but also the death of his wife. His sister-in-law also caused problems between him and his children.

Gonzales's sons, Ambrose and Narciso, became famous journalists. In 1891, they started a newspaper called The State in Columbia, South Carolina. Narciso used his newspaper to speak out against Benjamin "Pitchfork Ben" Tillman. Tillman was a U.S. Senator and former Governor of South Carolina. Narciso also spoke out against Tillman's nephew, Lieutenant Governor James H. Tillman. This helped ensure James lost the 1902 South Carolina governor race.

On January 15, 1903, James H. Tillman shot Narciso. Narciso died four days later. A memorial for Narciso was later built on Senate Street in Columbia. It was placed across from the State House.

Ambrose Gonzales is known in South Carolina as a pioneering journalist. He also wrote stories in the dialect of the Gullah people. The Gullah are an African-American group from the South Carolina and Georgia Low Country. In 1986, Ambrose was honored in the South Carolina Business Hall of Fame.

As Gonzales got older, he became ill. His sons sent him to Key West. There, Gonzales attended meetings of Cuban revolutionaries. He was later cared for in a hospital in Long Island, New York.

Ambrosio José Gonzales died on July 31, 1893. He is buried at Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx, New York City.

Gonzales died just a few years before the Spanish–American War of 1898. This war achieved what he had fought for so long: Cuba's freedom from Spanish rule with U.S. military help.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Ambrosio José González para niños

In Spanish: Ambrosio José González para niños

| James B. Knighten |

| Azellia White |

| Willa Brown |