Anthony Perkins facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Anthony Perkins

|

|

|---|---|

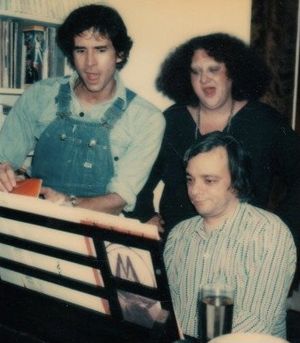

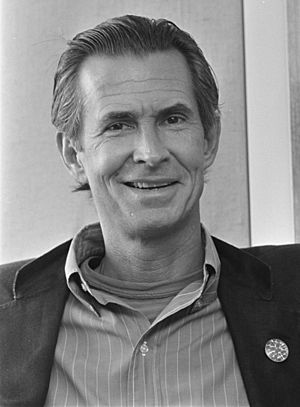

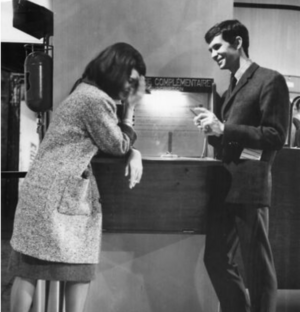

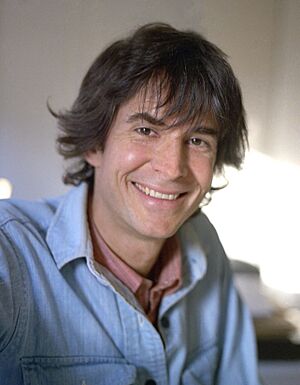

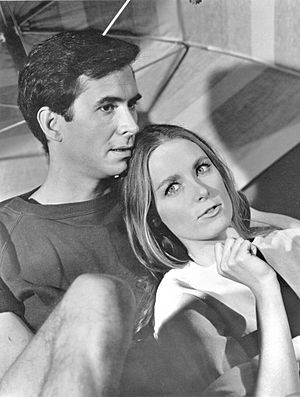

Perkins in 1975

|

|

| Born | April 4, 1932 New York City, U.S.

|

| Died | September 12, 1992 (aged 60) Los Angeles, California, U.S.

|

| Alma mater | Columbia University |

| Occupation | Actor |

| Years active | 1947–1992 |

| Spouse(s) |

Berry Berenson

(m. 1973) |

| Children |

|

| Parent(s) |

|

Anthony Perkins (born April 4, 1932 – died September 12, 1992) was an American actor. He is most famous for playing Norman Bates in Alfred Hitchcock's scary movie Psycho. He was born in New York City and started acting when he was a teenager. Perkins first appeared in movies and on Broadway plays. His role in the movie Friendly Persuasion (1956) earned him a Golden Globe Award. He also received an Academy Award nomination. This made him a popular young star.

Perkins acted in many movies. He often played romantic or serious characters. He starred with famous actors like Audrey Hepburn, Sophia Loren, and Gregory Peck. However, his role as the creepy motel owner Norman Bates in Psycho (1960) made him a star in horror movies. This role was so famous that he played Norman Bates again in three more Psycho movies.

After Psycho, Perkins also worked in European movies. He won awards like the Best Actor award at the Cannes Film Festival for Goodbye Again (1961). He later returned to the U.S. and acted in more films. These included Catch-22 (1970) and Murder on the Orient Express (1974).

In 1973, he married Berry Berenson. They had two sons together. Perkins continued acting in movies and television until his death in 1992. He passed away from an illness related to AIDS.

Contents

Early Life and First Steps in Acting

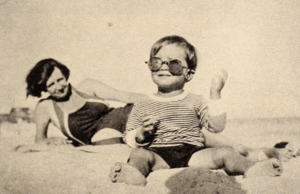

Anthony Perkins was born on April 4, 1932, in Manhattan, New York City. His father, Osgood Perkins, was also an actor. Sadly, his father died when Anthony was only five years old. This was a difficult time for young Anthony. He grew up mostly with his mother, Janet. His father being an actor sparked Anthony's interest in theater. He learned French as a child, which was useful later in his career.

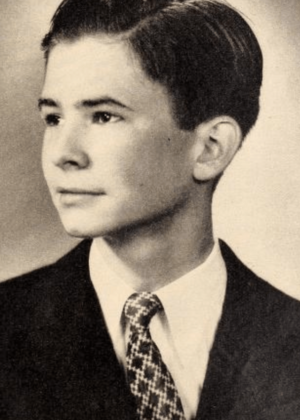

School Days and Summer Theater

When Perkins was ten, his family moved to Boston. He attended schools like Brooks School and Buckingham Browne & Nichols School. At school, he was known for playing the piano and doing impressions.

In the summers, he acted in summer stock programs. He played small roles in plays like Junior Miss. He also worked at the box office. This gave him early acting experience.

College and Early Career Choices

Perkins attended Rollins College and later Columbia University. He acted in school plays. His summer theater work confirmed his desire to be an actor. He began his professional career even before finishing college.

Career Beginnings: Movies and Broadway

First Films and Stage Success

While still in college, Perkins dreamed of being in movies. He got his first movie role in The Actress (1953). He acted alongside famous stars Jean Simmons and Spencer Tracy. In the movie, he played a Harvard student.

Perkins then became well-known on Broadway. He starred in the play Tea and Sympathy in 1954. He played a college student named Tom Lee. Critics and audiences praised his performance. This success made Hollywood interested in him again.

Hollywood Breakthrough and Serious Roles

The movie Friendly Persuasion (1956) was a big break for him. He played Josh Birdwell. He acted with Gary Cooper and Dorothy McGuire. He won a Golden Globe Award. He also received an Academy Award nomination. This made him a young star. Paramount Pictures signed him to a contract.

In Fear Strikes Out (1957), he played baseball player Jimmy Piersall. Critics praised his acting. He also starred in Westerns like The Lonely Man (1957) and The Tin Star (1957). In The Tin Star, he acted with Henry Fonda. These roles showed he could play many different types of characters.

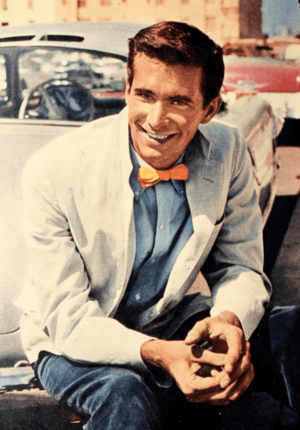

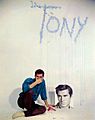

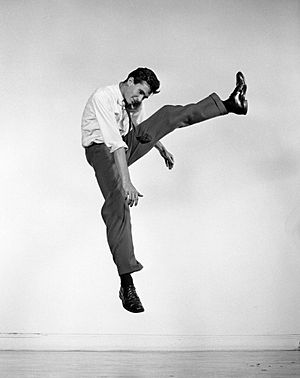

Becoming a Teen Idol

Perkins became a teen idol. He released pop music albums. His song "Moon-Light Swim" was a hit in 1957.

On Broadway, he starred in Look Homeward, Angel (1957-1959). He earned a Tony Award nomination for this role.

He starred in romantic films like Desire Under the Elms (1958) with Sophia Loren. He also appeared in The Matchmaker (1958) with Shirley MacLaine. He co-starred with Audrey Hepburn in Green Mansions (1959). He also had a serious role in On the Beach (1959). In this film, he acted alongside Gregory Peck and Fred Astaire. In 1960, he appeared in Tall Story, which was Jane Fonda's first movie.

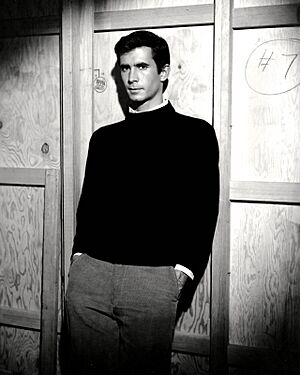

The Iconic Role: Norman Bates in Psycho

In 1960, Perkins played his most famous role. He was Norman Bates in Alfred Hitchcock's thriller Psycho. He played the shy owner of the Bates Motel who had a dark secret. Hitchcock chose him because of his previous acting work.

Psycho was a huge hit and a very important horror film. Perkins's acting as Norman Bates earned him praise. He received an award from the International Board of Motion Picture Reviewers. He became an international star. People often linked him to intense roles.

Also in 1960, he starred in the Broadway musical Greenwillow. He earned another Tony Award nomination for this.

Working in European Films

After Psycho, Perkins worked in Europe. He starred in Goodbye Again (1961) with Ingrid Bergman. He won Best Actor at the Cannes Film Festival for this role.

Other European films included Phaedra (1962) with Melina Mercouri. He also starred in Five Miles to Midnight (1962) with Sophia Loren.

He starred in The Trial (1962), which was directed by Orson Welles. He also appeared in the French comedy Une ravissante idiote (1964) with Brigitte Bardot.

Return to American Stage and Screen

Returning to the U.S., Perkins starred in the TV musical Evening Primrose (1966). This musical was by Stephen Sondheim. He also appeared in the Broadway play The Star-Spangled Girl (1966–67).

In 1968, he made Pretty Poison with Tuesday Weld. This was his first Hollywood film in years. He again played a complex character.

Supporting Roles and New Ventures

In the 1970s, Perkins took on supporting roles. These included films like Catch-22 (1970) and WUSA (1970) with Paul Newman. He also directed and starred in the Off-Broadway play Steambath (1970).

More films included Ten Days' Wonder (1971) with Orson Welles. He also appeared in Play It as It Lays (1972). Another film was the Western The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean (1972).

Writing and More Big Films

He co-wrote the successful mystery movie The Last of Sheila (1973). He wrote it with his friend Stephen Sondheim. They won an Edgar Award for their writing.

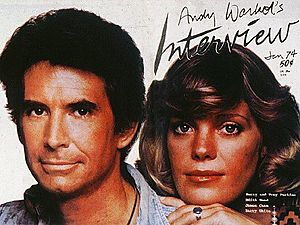

He joined an all-star cast in Murder on the Orient Express (1974). He also starred with Diana Ross in Mahogany (1975).

He returned to Broadway in Equus (1975-76). He played a psychiatrist in this play and received great praise.

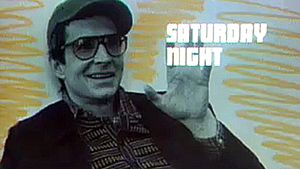

In 1976, he hosted Saturday Night Live. He made fun of his own image during the show. He acted in TV movies like First, You Cry (1978) and Les Misérables (1978). He also appeared in the Disney film The Black Hole (1979). He ended the 1970s with the Broadway hit Romantic Comedy (1979-80).

Return of Norman Bates and Later Work

In the 1980s, Perkins famously returned as Norman Bates. He played the character in three Psycho sequels. These were the hit Psycho II (1983) and Psycho III (1986). He also directed Psycho III, earning a Saturn Award nomination. His final Psycho role was in the TV movie Psycho IV: The Beginning (1990).

Other work in the 1980s included North Sea Hijack (1980). He also appeared in the TV mini-series For the Term of His Natural Life (1983). He directed the comedy Lucky Stiff (1988).

In the early 1990s, he appeared in horror films like Edge of Sanity (1989). He also hosted the TV series Chillers (1990). His final role was in the TV film In the Deep Woods (1992). This movie was released after his death.

His Acting Style

Anthony Perkins was known for being a very talented and dedicated actor. He learned a lot from other famous actors he worked with. These included Gary Cooper and Henry Fonda. He was also inspired by actors like Marlon Brando.

Perkins could play many different kinds of characters. He could be charming and funny, or serious and intense. He was especially good at playing characters who seemed a bit mysterious or troubled. Norman Bates in Psycho is a good example. Directors often said he was brave and trusted his instincts as an actor. He worked hard to make his characters believable and memorable. Many people thought he was a unique actor. He could be both disturbing and interesting to watch.

Personal Life

In 1973, Anthony Perkins married photographer and actress Berry Berenson. She was the younger sister of actress Marisa Berenson. Anthony and Berry had two sons. Oz Perkins (born 1974) became an actor and director. Elvis Perkins (born 1976) became a musician. They remained married until Anthony's death. Tragically, Berry Berenson died in the September 11 attacks in 2001. She was a passenger on American Airlines Flight 11. This was one of the planes that crashed into the World Trade Center.

Friendships and Interests

Perkins had many friends in Hollywood. One of his close friends was the famous Broadway composer and writer Stephen Sondheim. They worked together on the movie The Last of Sheila. Sondheim also wrote the TV musical Evening Primrose for Perkins.

Perkins was known to be a shy and thoughtful person. He enjoyed reading books and was interested in writing. He was also a fan of games like Scrabble.

Supporting Important Causes

Perkins believed in fairness and equality. In 1965, he participated in the Selma march for civil rights. He supported the fight for African Americans to have the right to vote. He joined other performers at a rally to support Martin Luther King Jr. and the marchers.

Death

Anthony Perkins learned he had AIDS while filming Psycho IV: The Beginning in 1990. He kept his illness private for two years. He passed away at his home in Los Angeles on September 12, 1992, at the age of 60. The cause of his death was pneumonia related to AIDS.

Before he died, Perkins wrote a statement. He said, "I have learned more about love, selflessness and human understanding from the people I have met in this great adventure in the world of AIDS than I ever did in the cutthroat, competitive world in which I spent my life." His ashes were placed in an urn with the inscription "Don't Fence Me In."

Legacy: How He Is Remembered

Anthony Perkins is remembered as a very important and influential actor. This is especially true for his role as Norman Bates in Psycho. This character is one of the most famous villains in movie history. Psycho itself is considered one of the greatest horror films ever.

Norman Bates has been mentioned in many songs, movies, and TV shows. For example, the character was referenced in the movie Scream.

Many of Perkins's other films are also admired. These include Friendly Persuasion and The Trial. Some of his movies have become cult favorites. This means they have a strong and dedicated group of fans. Examples are Pretty Poison and the TV musical Evening Primrose.

Perkins inspired many actors who came after him. He was known for his ability to play complex characters. He often played shy or nervous roles. Jane Fonda said he helped her become comfortable acting in front of the camera. For his work in movies and television, Anthony Perkins has two stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. His contributions to film, especially in the horror genre, continue to be recognized.

Stage Performances

| Year | Title | Role | Theatre | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1954–55 | Tea and Sympathy | Tom Lee | Ethel Barrymore Theatre, New York City | Broadway (replacement for John Kerr) |

| 1957–59 | Look Homeward, Angel | Eugene Gant | Ethel Barrymore Theatre, New York City | Broadway |

| 1960 | Greenwillow | Gideon Briggs | Alvin Theatre, New York City | |

| 1962 | Harold | Harold Selbar | Cort Theatre, New York City | |

| 1966–67 | The Star-Spangled Girl | Andy Hobart | Plymouth Theatre, New York City | |

| 1970 | Steambath | Tandy | Truck and Warehouse Theater, New York City | Off-Broadway (also director) |

| 1974 | The Wager | N/A | Eastside Playhouse, New York City | Off-Broadway (director) |

| 1975–76 | Equus | Martin Dysart | Plymouth Theatre, New York City | Broadway (replacement for Anthony Hopkins) |

| 1979–80 | Romantic Comedy | Jason Carmichael | Ethel Barrymore Theatre, New York City | Broadway |

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Anthony Perkins para niños

In Spanish: Anthony Perkins para niños