Booth's Uprising facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Booth's Uprising |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms | |||||||

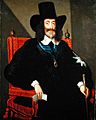

Lead conspirator John Mordaunt, 1st Viscount Mordaunt |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

c.4000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1 killed | 30 killed | ||||||

Booth's Uprising, also known as Booth's Rebellion, was a short and unsuccessful attempt in August 1659 to bring back Charles II of England as king. It happened in North West England and was led by George Booth. This event took place during a time of great political confusion after Richard Cromwell stepped down as leader of England.

The uprising was meant to be part of a bigger national rebellion organized by John Mordaunt, 1st Viscount Mordaunt. However, only the part led by Booth had any initial success. Other local rebellions either didn't start or were quickly stopped. Booth managed to capture the important city of Chester, and commanders in Liverpool and Wrexham joined him. But he soon found himself alone.

On August 19, a government army led by John Lambert defeated Booth's forces at Winnington Bridge near Northwich. This battle is sometimes called the last battle of the English Civil War. Liverpool and Chester surrendered soon after. Booth was caught and briefly put in prison, but he wasn't punished. The government of England collapsed in 1660, leading to the return of the monarchy. Booth was rewarded with a special title for his efforts.

Contents

Why Did Booth's Uprising Happen?

Even after losing the First English Civil War, King Charles I still had a lot of power. He tried to team up with Scottish groups and moderate members of Parliament to get his throne back. These moderates, who wanted a king with limited power, included many Presbyterians. They wanted a state church.

They were opposed by a smaller group called Independents, who didn't want any state church. There were also political radicals who wanted big changes. After Charles I was defeated in the 1648 Second English Civil War, he kept trying to start another uprising. Some army leaders, like Oliver Cromwell, believed that only his death could bring peace.

Most members of Parliament were against putting the king on trial. But after some were removed, only a small number voted for it. Charles I was executed in January 1649. After this, those who supported the king, called Royalists, looked to his son, Charles II of England, who was living in exile.

The Third English Civil War in 1651 failed to bring the king back. Many in Parliament didn't like the army's strong role in government. This led to Cromwell becoming Lord Protector in 1653. After he died in September 1658, his son Richard took over. Many people in Parliament wanted the monarchy back, and the government was very unstable. In May 1659, the army removed Richard Cromwell. This political uncertainty was something the Royalists hoped to use.

People were also worried about big social and religious changes. They felt the army and Parliament were supporting radical religious groups. They also thought the traditional leaders of society were losing their power. This fear grew when local militia groups were put in charge of people who were not from the traditional upper classes.

The Plan to Bring Back the King

After 1648, several Royalist revolts failed. This led to the creation of the Sealed Knot, a small group of nobles who planned future actions in England. They reported to Edward Hyde and the Earl of Ormond. This group didn't want to work with other groups who opposed the government, like the moderate Presbyterians.

The Sealed Knot's plans were often ruined because one of its members, Sir Richard Willis, was secretly working for Cromwell's spy chief. By 1659, Hyde and the Sealed Knot thought the government would fall apart on its own. But another group, called the "Action Party," argued that an uprising was needed right away.

King Charles II was getting impatient. Hyde decided to support the uprising to keep his influence. On March 1, 1659, Charles created the "Great Trust and Commission." This group included the six members of the Sealed Knot plus John Mordaunt, 1st Viscount Mordaunt. Mordaunt realized his colleagues weren't very excited about a revolt. So, he started recruiting others.

He brought in former Royalist officers and moderate Presbyterians. The plan was designed by Roger Whitley. He suggested that since they didn't know when outside help would arrive, they should have many small, local uprisings. This would be more flexible. The idea was to unite poor ex-Royalists with unhappy Presbyterians. Charles was supposed to promise to fix religious differences to get Presbyterian support.

Mordaunt couldn't get support from a major general in London. So, he focused on important ports like Bristol and Lynn. Other big uprisings were planned for Shrewsbury, Warwick, and Worcester. Smaller actions were planned elsewhere, including in Cheshire.

By July 1659, Mordaunt felt confident. He believed many important people were turning to the King. He claimed support from powerful Presbyterians. The exiled King's court also got involved. The Duke of York wrote to a Royalist in North Wales, saying "the time draws near for action." Mordaunt feared more delays would lead to their plans being discovered. So, he ordered a general uprising for August 1.

The Plot in Cheshire and Lancashire

Mordaunt first thought Cheshire wouldn't be a good place for an uprising. There weren't many strong Royalist leaders there. But Sir George Booth became an option. Booth had fought for Parliament during the First Civil War. He was elected to Parliament for Cheshire in 1646. He was part of the Presbyterian group that was powerful in Parliament.

However, Booth was later prevented from attending Parliament because he was suspected of being involved in an uprising in 1655. He also called the military governors "Cromwell's hangmen." His history of opposing the government, his social standing, and his wealth made him attractive to the "Great Trust" group. After meeting Mordaunt in London, he joined the plan. By July, he had promises of local support.

Cheshire wasn't usually a rebellious area. But certain things made it ready for an uprising. During the First Civil War, Booth's main rival for leadership was a powerful man named Sir William Brereton. But Brereton retired, leaving a power gap. Also, the traditional leaders of society were losing their power under the government. A very unpopular military governor ruled the area from 1655 to 1656.

Similar issues were happening in nearby Lancashire. Local Presbyterians continued to pray for Charles II, even after it was banned in 1650. They stayed loyal in 1651 because of the strong Catholic presence, which was linked to Royalism. But in July 1659, Parliament passed a new law that further reduced the power of the old leaders. It was also falsely claimed that local religious groups, like Quakers, were planning a revolt. Many saw these events as proof of a social revolution.

The National Uprising Begins

Even with all the political problems, the government's spy network was still working well. They knew about a planned revolt. As early as July 9, orders were sent to local militias. The Navy also blocked a port where Charles was likely to sail from. On July 28, the authorities got clear proof of the plan. They intercepted letters from Mordaunt to Edward Massey with final instructions for an uprising in Gloucester.

Knowing the government was aware probably stopped many people from joining on August 1. A discouraging letter from the Sealed Knot also reached local plotters on July 31. Local uprisings began as planned on August 1. But it quickly became clear that far fewer people showed up than expected. Several meeting points were already being watched by the local militia.

A group of 120 horsemen gathered in Sherwood Forest. They planned to take Newark, but they were chased and scattered. In Shropshire, Charles Lyttelton was supposed to surprise Shrewsbury. But only 50 men joined him. They marched a short distance before giving up. Mordaunt, who escaped arrest on July 28, gathered about 30 men in Surrey. But he fled when it was clear the uprising was failing. The rebels were quickly stopped everywhere.

Booth's Uprising in Cheshire

In Cheshire, Booth thought about canceling the uprising. But July 31 was a Sunday, and many Presbyterian church leaders had told their congregations to join him. This meant men were already gathering and weapons were being collected. So, the leaders had no choice but to continue. Booth gathered several hundred supporters at Warrington on August 1.

The senior government officer in Lancashire was Colonel Thomas Birch. He was Booth's colleague during the First English Civil War. Birch knew about the intercepted letters but did little to stop the uprising. His loyalties might have been divided.

Booth marched towards Chester. On August 2, he held a new meeting at Rowton Heath. There, he issued a "Declaration" and another paper called "A Letter to a Friend." These papers didn't mention Charles II. They only said the rebels wanted members who had been removed from Parliament to be allowed back. Or, they wanted new elections for a new Parliament.

Since he was sure of Royalist support, Booth focused on getting help from fellow Presbyterians. He also criticized the government's corruption. He promised the "undeceived part of the Army" that he would increase their pay. This approach worked quite well. Unlike other parts of the country, he gained the support of "almost all the local gentry and nobility," including former Royalists.

On August 3, supporters in Chester let Booth into the city. As more people joined, his force grew to about 3,000. The governor and his militia took shelter in Chester Castle. Booth couldn't get them out without special cannons. So, he left 700 men to surround the castle. He then marched towards Manchester with most of his rebels.

He was joined by the Earl of Derby, head of a famous Royalist family. Gilbert Ireland, a member of Parliament for Liverpool, also joined. Another group, led by Randolph Egerton, left Chester and went into Wales to Chirk Castle. This was the home of former Parliamentarian commander Sir Thomas Myddelton. Myddelton joined Egerton and led the rebels from Chirk to Wrexham, the main town in the area. Many of Myddelton's followers were Royalists. Unlike Booth, Myddelton openly declared Charles as King on August 7.

The Battle of Winnington Bridge

The government's foot soldiers from London joined the cavalry at Market Drayton on August 14. General Lambert reached Nantwich on August 15. Booth's forces retreated towards Chester. On the same day, two warships blocked the mouth of the River Dee. This stopped any help from reaching the rebels by sea.

Lambert quickly moved towards Northwich. On August 18, he almost surprised Booth's forces. They were saved only by a quick retreat ordered by Roger Whitley. Lambert's scouts found Booth's rearguard in the Delamere Forest. They then camped for the night at Weaverham.

Early on August 19, most of Booth's army was ready for battle. They were on high, uneven ground near Hartford. This ground was not good for cavalry. But Lambert attacked anyway. He pushed their outposts back to Winnington Bridge. The rebels tried to make a stand there. But they retreated after a "fierce but brief" fight.

The rebel cavalry quickly ran away. Their foot soldiers escaped into nearby enclosed areas. The government army didn't chase them. Few people were killed on either side. Lambert reported that 30 rebels were killed at Winnington Bridge. The only important rebel casualty was Captain Edward Morgan, who died while covering their retreat.

How the Uprising Ended

Most of the rebel leaders fled after the battle and then surrendered. Chester surrendered to Lambert on August 21. Liverpool surrendered soon after. The rest of Cheshire and Lancashire were back under government control within a week. The last rebels to give up were in North Wales. They were led by Myddelton's oldest son, Thomas. They went into Chirk Castle. They finally surrendered at the end of the month.

Booth fled south after Winnington Bridge. He traveled in a carriage and dressed as a woman, calling himself "Lady Dorothy." He was finally arrested at Newport Pagnell. A suspicious innkeeper noticed his "female" guest asking for a barber and a razor. By the end of August, he was in prison in London. Mordaunt himself avoided being caught and escaped the country in September. Even though he heard about the failures outside Cheshire, Charles II traveled to St. Malo to join Booth. But he learned of Booth's defeat just before sailing.

What Happened Next?

Almost all the leaders of the Cheshire uprising were captured, except for Whitley. But because of the political situation, they were mostly not punished. Belasyse was arrested on August 16. Booth accused him of being the main leader, and he was held in the Tower of London. Most of the lower-ranking prisoners were quickly released. None of the higher-ranking people, including Booth, were put on trial or lost their property.

Mordaunt was not discouraged by the failure. But his plans became unimportant because of the actions of General George Monck in late 1659 and 1660. Monck's actions led to members of Parliament, like Booth, being allowed back into Parliament. Charles II appointed Belasyse to represent him in talks with Monck. These talks led to the return of the monarchy in May 1660. Booth was sent by Parliament to escort Charles II to London.

Booth was given the title 1st Baron Delamer. However, because their uprising failed just a few months before the king returned, he and many other Cheshire rebels received relatively few rewards for their efforts. This disappointment, along with local dislike for Charles's religious policies after 1661, meant that Booth's Uprising helped create a group of people in the region who opposed the king's court. Booth's son, Henry, became a strong supporter of the Whig party. He supported the Glorious Revolution in 1688 against James II.

Images for kids

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |