Tories (British political party) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Tories

|

|

|---|---|

| Leader(s) | |

| Founded | 1678 |

| Dissolved | 1834 |

| Preceded by | Cavaliers |

| Succeeded by | Conservative Party |

| Ideology |

|

| Political position | Centre-right to right-wing |

| Religion | |

| Colours | Blue |

The Tories were a group of politicians in the British Parliaments. They were like a political team or party. They first appeared around 1679. At that time, another group called the Whigs wanted to stop James, Duke of York from becoming king. This was because he was Catholic. The Tories did not want a Catholic king either. But they believed that the king's right to rule came from his birth, not from Parliament. They thought this was important for a stable country.

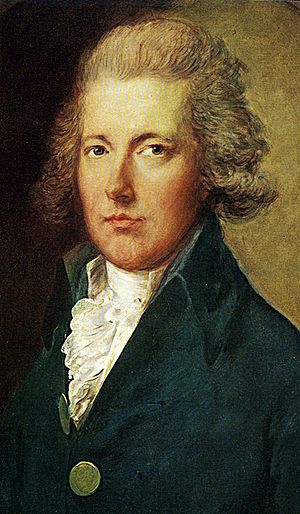

After George I became king in 1714, the Tories were out of power for almost 50 years. They stopped being an organized party in the early 1760s. But the name "Tory" was still used by some writers. A few decades later, a new Tory party grew strong. They were in charge of the government from 1783 to 1830. Important leaders during this time were William Pitt the Younger and Robert Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool.

In 1831, the Whigs won control of Parliament. This election was mostly about changing how elections worked. The Representation of the People Act 1832 removed "rotten boroughs." These were small areas that had very few voters but still elected Members of Parliament (MPs). Many of these were controlled by the Tories. After the 1832 elections, the Tories had only 175 MPs.

Under the leadership of Robert Peel, the Tories started to change. They became what is now known as the Conservative Party. Peel wrote a plan called the Tamworth Manifesto. However, in 1846, Peel changed some laws about grain, called the Corn Laws. This caused the party to split. The group led by Derby and Benjamin Disraeli became the modern Conservative Party. Even today, members of the Conservative Party are often called Tories.

Contents

What's in a Name?

The Tories were first known as the Court Party. The word Tory was originally an insult. It came from an old Irish word meaning "outlaw" or "robber." This word became part of English politics during a big argument in 1678–1681. This argument was about whether James, the Duke of York, could become king.

The word Whig was also an insult. It came from a Scottish word for a "cattle driver." It was first used for a group in Scotland who opposed King Charles I.

So, the Whigs were those who wanted to stop James, the Duke of York, from becoming king. They were called Petitioners. The Tories were those who were against stopping him. They were called Abhorrers.

In 1757, a writer named David Hume explained how these names became popular. He said that the King's supporters called their opponents "Whigs." This was because the Whigs were like a group in Scotland who opposed the King. And the King's opponents called the King's supporters "Tories." This was because the Tories were like Irish outlaws. These names, which started as insults, became common political terms.

A Look Back at Tory History

English Civil War and Royal Support

The first Tory party's ideas came from the English Civil War. This war divided England between the Cavaliers and the Roundheads. Cavaliers supported King Charles I. Roundheads supported Parliament. The war started because the King wanted to raise taxes without Parliament's permission.

At first, many of the King's supporters wanted to fix problems. But Parliament became more extreme. This made many reformers join the King's side. The King's party included those who supported strong royal power. It also included Parliament members who felt Parliament was taking too much power. They especially worried about changes to the Church of England. They believed the Church supported the King's rule. By the late 1640s, Parliament wanted to make the King powerless. They also wanted to change the Church of England.

This plan was stopped by Oliver Cromwell and his army. The army took power from Parliament. King Charles I was executed. For 11 years, Britain was ruled by the army. When King Charles II returned to power, he got back much of his father's authority. But no British king after him would try to rule without Parliament. After the Glorious Revolution of 1688, political problems were solved through elections. They were not solved by fighting. Charles II also brought back the Church of England. His first Parliament strongly supported the King. They passed laws to make the Church strong and punish those who disagreed.

In the late 1660s and 1670s, Charles II's government faced many problems. Powerful groups, including some who had fought in the Civil War, wanted Parliament to have more power. They also wanted more freedom for Protestants who were not part of the Church of England. These groups soon became the Whigs.

It was too risky to directly attack the King. So, his opponents claimed there were secret Catholic plots. These plots were not real. But they showed two real problems. First, Charles II had secretly agreed to try to make England Catholic. Second, his younger brother, James, Duke of York, had become Catholic. Many Protestants saw this as a serious threat.

The Whigs tried to link a Tory leader to a fake plot. They said this Tory was planning to murder someone. The government found letters about this plan, and it failed. In 1681, the Whigs started calling these supposed plotters "Tories." Soon after, those who opposed the Whigs started calling themselves Tories.

The Exclusion Crisis and the Glorious Revolution

The Tories believed in a strong king. They saw the Whigs as trying to weaken the king's power. The main issue was the Exclusion Bill. This bill aimed to stop James, Duke of York, from becoming king because he was Catholic. The Tories believed that Parliament should not choose the king. They thought the king's right to rule came from birth.

The Tories won in the short term. The Parliaments that supported the Exclusion Bill were shut down. Charles II ruled without much challenge. When he died, James became king easily. A rebellion by Monmouth, a Whig choice for king, was quickly crushed.

However, the Tories' beliefs were later challenged. Besides a strong king, Tories also supported the Church of England. They wanted it to be the only official church. But King James II wanted religious freedom for Catholics. This was a big problem for many Anglicans. James tried to use the Church of England to promote his policies. This made some Tories support the Glorious Revolution of 1688.

This revolution resulted in a king chosen by Parliament. This king had to follow laws made by Parliament. These were ideas the Tories had first opposed. The only comfort for Tories was that the new kings were close to the original line of succession. William III was James II's nephew, and his wife Mary was James's daughter. The Act of Toleration 1689 also gave more rights to Protestant groups who were not part of the Church of England. Many bishops who refused to support the new monarchs were removed. This allowed the government to appoint new bishops who supported the Whigs. So, the Tories' main goals had failed. But the monarchy and the state Church still existed.

Competing for Power

Even though their original ideas were challenged, the Tories remained a strong party. This was especially true during the reign of Queen Anne. During this time, Tories and Whigs fought fiercely for power. There were many elections where they tested their strength.

King William III saw that Tories were generally more supportive of royal power than Whigs. He used both groups in his government. At first, his government was mostly Tory. But it slowly became controlled by the "Junto Whigs." This group was opposed by other Whigs and the Tories.

Queen Anne had some Tory sympathies. She removed the Junto Whigs from power. But after a short time with only Tory ministers, she went back to balancing the parties. Her moderate Tory ministers, the Duke of Marlborough and Lord Godolphin, supported this.

The long War of the Spanish Succession (which started in 1701) made most Tories oppose the government by 1708. So, Marlborough and Godolphin were leading a government mostly made of Whigs. Queen Anne became unhappy with relying on the Whigs. In 1710, the Whig government tried to punish a very Tory preacher. This made the government unpopular. In the spring of 1710, Anne fired her Whig ministers and replaced them with Tories.

The new Tory government was led by Robert Harley and Viscount Bolingbroke. They had strong support in Parliament after the 1710 election. This Tory government signed the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713. This pulled Great Britain out of the war. Queen Anne even created new Tory lords to pass the peace treaty. After a disagreement, Anne fired Harley in 1714. Bolingbroke became her chief minister, and Tory power seemed to be at its highest. However, Anne was very ill and died within days. Bolingbroke had no clear plan for who should be the next king. George, Elector of Hanover, became king peacefully.

Out of Power

When the new King George I arrived, he formed a government made only of Whigs. The new Parliament, elected in 1715, also had a large Whig majority. Many Tories lost their jobs in the government, army, navy, and church. This continued for 45 years.

The Whig government, with the King's support, stayed in power for many decades. Elections were not very frequent. The Tories had a lot of support in rural England. But the way elections were set up meant they could never win a majority in Parliament. The Tories were a permanent minority. They were completely shut out of government. This made the Tories stick together. The Whigs offered few chances for Tories to switch sides.

Being shut out of power made many Tories support Jacobitism. This was the movement to bring back the Stuart family to the throne. In 1714, the French ambassador noted that more Tories were becoming Jacobites. In 1715, he wrote that Tories seemed ready for a civil war. The former Tory leader, Lord Oxford, was arrested. Bolingbroke and another Tory leader fled to France to join the Pretender.

Riots against King George I's crowning and the new Whig government broke out. People supported the Jacobites and local Tory candidates. This led the Whig government to pass laws to strengthen their power. They also increased the army.

The French King Louis XIV had promised arms but no troops. This promise disappeared when Louis died in 1715. A planned uprising in England failed. But the Scots started their own uprising. Charles XII of Sweden was willing to help the English Tories. He planned to send troops to put the Pretender on the throne. But this plot was discovered in 1717. Charles's death in 1718 ended these hopes.

During a split among the Whigs in 1717, the Tories refused to support either side. Their combined efforts helped the opposition win some battles, like stopping a bill in 1719. In 1722, a Whig leader suggested letting some Tories into the government. He thought this would divide them. But King George I was strongly against a Tory Parliament.

A public outcry over a financial scandal made the Tories believe a Jacobite uprising would succeed. But a plot to put the Pretender on the throne, called the Atterbury Plot, was discovered. The Whig Prime Minister Robert Walpole decided not to punish the Tories involved. But the Tories were discouraged. They stayed away from Parliament for a while. When George II became king in 1727, the Tories had only 128 MPs. This was their lowest number yet.

The Tories were divided on whether to work with the Whigs who opposed Walpole. Most Tories were against it. But in 1730, the Pretender sent a letter telling them to unite against the government. For the next ten years, the Tories worked with the opposition Whigs. They couldn't openly support Jacobitism because it was treason. So, they used old Whig arguments. They complained about government corruption and high taxes. They opposed a large army and spoke against "tyranny." Walpole claimed that true Jacobites pretended to support "revolution principles" to hide their real goals.

In 1737, Frederick, Prince of Wales, asked Parliament for more money. This split the Tories, and the request was defeated. In 1739, war broke out against Spain. This led to new plots among Tories for a Jacobite uprising. The death of a Tory leader in 1740 broke up the alliance between Tories and opposition Whigs. Many Tories did not vote on a motion to remove Walpole. In the 1741 election, 136 Tories were elected.

The Tories started working with the opposition Whigs again after another letter from the Pretender in 1741. He told them to work together to hurt the government. As a result, 127 Tories joined the opposition Whigs. They successfully voted against Walpole's choice for an elections committee chairman. They continued to vote against Walpole until he had to resign in 1742. The Pretender praised the Tories for their actions.

In 1743, war started between Britain and France. Later that year, English Tories sent a message to the French asking for help to bring back the Stuart family. They asked for 10,000 French soldiers. The French King Louis XV said he would help if there was enough proof of English support.

A French agent visited England to see how strong Jacobitism was. He told Tory leaders that the French king would meet all their demands. In November 1743, the French officially said they would restore the Stuart family. They planned an invasion led by the Pretender's son, Charles Edward Stuart. A "Declaration of King James" was written by Tory leaders. It was to be published if the French landed successfully.

However, the Whig government learned about the invasion from a spy. King George told Parliament in February 1744 that a French invasion was planned. It would be helped by "disaffected persons from this country." The House of Commons supported the King. The Tories voted against this, which seemed to show the French how many supporters they had in Parliament. The Tories also opposed increasing the army.

On February 24, a storm scattered the French invasion fleet. Suspected Jacobites were arrested. The French cancelled their invasion. Charles Stuart, still in France, wanted to start a Jacobite uprising. But English Tories would only support a Scottish uprising if the French invaded near London at the same time.

In December 1744, a new government was formed. It included a few Tories in minor roles. Some Tories refused jobs because they represented Jacobite areas. One Tory who accepted office, Sir John Cotton, did not swear loyalty to King George. He told the French King that he still wanted a Jacobite French invasion. He even said Tories in office would try to send more British soldiers to Flanders. This would help a French invasion. After a Tory leader, Lord Gower, joined the government, the Tories no longer saw him as their leader. They chose a Jacobite, the Duke of Beaufort, instead.

In June 1745, Tory leaders told the Jacobite court that if Prince Charles landed with troops, there would be no opposition. They sent a request to France for 10,000 troops and 30,000 weapons to be landed in England.

Charles went to Scotland in July without telling the Tories or the French. He had few troops. After he landed, a supporter wrote that London, Sir John Hynde Cotton, and other English leaders wanted troops landed near London. They could not rise up without troops to support them. But they would join Charles if he could reach them. During the Jacobite rising of 1745, Charles could not contact the English Tories. A spy reported in December that they were being watched. They would declare for Charles if he reached London or if the French invaded. But Charles retreated from England, and the French never landed. So, the English Tories did not feel safe to join the uprising.

After the uprising failed, Charles's secretary told the government about the Tories' plot. The government decided not to prosecute them. Most Tory lords boycotted the trial of the Scottish rebels. After the Duke of Cumberland brutally put down the Scots, English Tories started wearing the plaid as a symbol.

Historians have debated how committed the Tories were to Jacobitism. Some believe they were mostly Jacobite until 1745. Others question this. It is hard to know for sure because many families destroyed letters that could prove Jacobite leanings. However, most Tories did not actively join the Jacobite uprisings.

In 1747, Prince Frederick invited the Tories to join him. He promised to end party differences when he became King. Leading Tories accepted his offer. But they refused to join a coalition with the Whigs. The 1747 election resulted in only 115 Tory MPs. This was their lowest number. After Jacobite riots in Oxford in 1748, the government wanted to control the University of Oxford. It was seen as a center for Jacobitism and Toryism.

After the deaths of Tory leaders in 1749 and 1752, the Tory party was "without a head." They were discouraged and scared. By 1764, a writer named Horace Walpole noted that the Tory party had declined. He said that Jacobitism, which was the secret reason for the Tory party, was gone. The political fights were now more about power than about old party differences. The Tories still existed, but they were not strong enough to change anything.

Friends of Mr. Pitt

Historians agree that the Tory party declined sharply in the 1740s and 1750s. It stopped being an organized party by 1760. There were no organized political parties in Parliament between the late 1750s and early 1780s. Even the Whigs were not a clear party. Parliament was filled with competing groups. All of them claimed to be Whigs. Or they were independent members not tied to any group.

When George III became king, the old political differences disappeared. The Whig groups became separate parties. All of them called themselves Whigs. The main difference in politics was between the "King's Friends" and those who opposed the king. The ban on Tories working in government ended. This caused the Tories to split into several groups. They stopped being a single political party. The word "Tory" became just an unfriendly name for politicians close to George III. Prime Ministers like Lord Bute and Lord North were called "Tory." But they thought of themselves as Whigs. No politician called himself a Tory between 1768 and 1774.

Later, opponents used the term Tories for those who supported William Pitt the Younger (Prime Minister from 1783–1801 and 1804–1806). This term came to mean the political group against the "Old Whigs." It also meant those against the new ideas from the American and French Revolutions. The Whig party split in 1794. A conservative group joined Pitt's government. This left a smaller opposition group.

Pitt himself did not like the "Tory" label. He preferred to be called an independent Whig. He believed the government was well-balanced. He did not want to give the king more power, unlike the old Tories.

The group around Pitt the Younger became very powerful in British politics from 1783 to 1830. After Pitt died in 1806, his ministers called themselves the "Friends of Mr Pitt." They did not call themselves Tories. Pitt's successor, Spencer Perceval, also never used the Tory label. After his death in 1812, the government of Lord Liverpool also refused the name "Tory."

Generally, Tories were linked to smaller landowners and the Church of England. Whigs were more linked to trade, money, larger landowners, and other Protestant churches. Both groups still believed in the political system of the time. The new Tory party was different from the old one. It had many former Whigs who were unhappy with their old party. While they respected the King, Tory governments did not give the King more power than Whig ones. George III's attempts to control policy had failed in the American War. After that, his role was limited. In foreign policy, the new Tories were very different. The old Tories wanted peace and to stay out of foreign affairs. The new Tories were more warlike and supported the British Empire.

The Conservative Party

After 1815, the Tories became known for stopping public protests. But the Tories changed a lot under Robert Peel. Peel was an industrialist, not a landowner. In his 1834 Tamworth Manifesto, Peel described a new idea: fixing problems while keeping what was good. Peel's later governments were called Conservative, not Tory. But the older term "Tory" is still used.

In 1846, the Conservative Party split over free trade. The group that wanted to protect local goods refused the "Conservative" name. They preferred to be called Protectionists or even to bring back the name "Tory." By 1859, Peel's supporters joined the Whigs and other groups to form the Liberal Party. The remaining Tories, led by the Earl of Derby and Benjamin Disraeli, officially adopted the name Conservative Party.

Election Results

| Election | Leader | Seats | +/– | Position | Government |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1661 | Sir Edward Hyde |

379 / 513

|

Majority | ||

| March 1679 | John Ernle |

137 / 513

|

Minority | ||

| October 1679 |

210 / 513

|

Minority | |||

| 1681 | Charles II of England |

193 / 513

|

Minority | ||

| 1685 | James II of England |

468 / 513

|

Majority | ||

| 1689 | The Marquess of Carmarthen |

232 / 513

|

Minority | ||

| 1690 |

243 / 513

|

Minority | |||

| 1695 |

203 / 513

|

Minority | |||

| 1698 |

208 / 513

|

Minority | |||

| January 1701 |

249 / 513

|

Minority | |||

| November 1701 |

240 / 513

|

Minority | |||

| 1702 | The Earl of Godolphin and The Duke of Marlborough |

298 / 513

|

Majority | ||

| 1705 | The Duke of Marlborough |

260 / 513

|

Majority | ||

| 1708 | The Earl of Godolphin |

222 / 558

|

Minority | ||

| 1710 | Robert Harley |

346 / 558

|

Majority | ||

| 1713 |

369 / 558

|

Majority | |||

| 1715 | The Viscount Bolingbroke |

217 / 558

|

Minority | ||

| 1722 | Sir William Wyndham |

169 / 558

|

Minority | ||

| 1727 | The Viscount Bolingbroke |

128 / 558

|

Minority | ||

| 1734 |

145 / 558

|

Minority | |||

| 1741 | Sir Watkin Williams-Wynn |

136 / 558

|

Minority | ||

| 1747 |

117 / 558

|

Minority | |||

| 1754 | Edmund Isham |

106 / 558

|

Minority | ||

| 1761 |

112 / 558

|

Minority |

| Election | Leader | Seats | +/– | Position | Government |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1774 | Lord North |

343 / 558

|

– | – | Majority |

| 1780 |

260 / 558

|

Majority | |||

| 1784 | William Pitt the Younger |

280 / 558

|

Majority | ||

| 1790 |

340 / 558

|

Majority | |||

| 1796 |

424 / 558

|

Majority | |||

| 1802 | Henry Addington |

383 / 658

|

Majority | ||

| 1806 | The Duke of Portland |

228 / 658

|

Minority | ||

| 1807 |

216 / 658

|

Majority | |||

| 1812 | The Earl of Liverpool |

400 / 658

|

Majority | ||

| 1818 |

280 / 658

|

Majority | |||

| 1820 |

341 / 658

|

Majority | |||

| 1826 |

428 / 658

|

Majority | |||

| 1830 | The Duke of Wellington |

250 / 658

|

Minority | ||

| 1831 |

235 / 658

|

Minority | |||

| 1832 |

175 / 658

|

Minority |

- Note that the results for 1661–1708 are for England only.