Brittany Campaign facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Campaign of Brittany (1590-1598) |

|

|---|---|

| Part of the Anglo-Spanish Wars | |

Embarkation of Spanish troops

|

|

| Type | Establish a base of operations |

| Location | Brittany, France, English Channel and British Isles |

| Planned | 1590 |

| Planned by | Spanish Empire |

| Objective | Threat to England |

| Date | 1590–1598 |

| Outcome | Ended with the Peace of Vervins in May, 1598. |

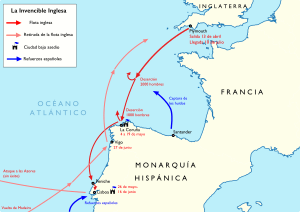

The Brittany Campaign was a time when Spain took control of a part of Brittany, France. It started in the summer of 1590. This happened when Philippe-Emmanuel de Lorraine, Duke of Mercœur, who was the governor of Brittany, offered the port of Blavet to King Philip II of Spain. This port would allow Spain to keep its fleet there. The Spanish control officially ended on May 2, 1598, with the signing of the Peace of Vervins.

Spain used Brittany as a main base. From there, they could protect their treasure ships, stop English naval attacks, raid the English coast, and help the Catholic League. Their main goal was to eventually invade England.

Contents

Why the Brittany Campaign Started

On September 22, 1588, the remaining ships of the Grand Armada returned to Spanish ports. Their ships were damaged, their crews were tired, and many sailors were sick.

The failure of the plan to invade England was a big problem for Philip II. It affected people's spirits more than it damaged Spain's navy. Records show that out of 123 ships that sailed, only 31 were lost. Most of these were smaller ships, not the large galleons.

Still, Philip II did not give up on invading England. In his last years as king, he tried several times to carry out this plan. These efforts were part of a bigger conflict between Spain and England, which included the Brittany campaign.

Spain needed to protect its coasts from possible English attacks. So, they worked to rebuild their navy and replace lost sailors.

Most of the ships that survived the Armada were sent to Santander for repairs. Only a few ships, like the galleons "San Bernardo" and "San Juan," remained in La Coruña.

In November 1588, Philip II ordered 21 new, large galleons to be built. Twelve of these were built in the Cantabrian ports and were called "The twelve apostles." The other ships were built in Portugal, Gibraltar, and Vinaroz. All of them were ready for service very quickly.

Soon after the Armada returned, troops were called up in all coastal areas. This was to prepare for an expected English attack. But winter arrived, reducing the fear of an immediate counterattack.

This allowed the infantry units that returned with the Armada to move inland for the winter. This helped Santander, which had been housing many soldiers.

In early 1589, these units were reorganized into two large groups called tercios. They were led by Don Agustín de Mexía and Don Francisco de Toledo. Don Juan del Águila's tercio, which had not been part of the Armada, also joined them.

English Attacks on La Coruña and Lisbon

The situation changed when England launched its own attack, hoping to take advantage of Spain's weakened state.

In the spring of 1589, 180 English ships with 27,667 men sailed from Plymouth. They were led by Sir Francis Drake and Sir John Norris. Their goals were to destroy the remaining Spanish Armada ships in Santander, then capture Lisbon and the Azores. They also wanted to help Don António, Prior of Crato become the king of Portugal.

As this large fleet neared the Spanish coast, they heard that the Armada was in La Coruña. Drake decided to change his plans and attack that port. He hoped to surprise and destroy the Armada ships there.

This information was wrong. The Armada was in Santander, unaware of the attack. Only a few ships were in La Coruña. Drake soon realized his mistake. But for unknown reasons, he decided to continue the attack. After overcoming weak resistance, his forces landed on Santa Lucía beach on May 4.

The Viceroy of Galicia, Juan Pacheco de Toledo, could only gather 1,500 soldiers. Despite this, Drake's attempts to take La Coruña failed. The Spanish forces and the local people fought back strongly. On May 18, Drake had to load his troops back onto the ships and left the next day. The English lost between 1,000 and 1,500 men. On the Spanish side, three galleons were burned by their own crews to prevent them from being captured.

From Galicia, the English ships sailed along the Portuguese coast in early June. They tried to capture Lisbon but failed after intense fighting. Drake suffered a major defeat, losing about 10,000 men (dead and wounded) and nine ships. The expedition was a total failure. Only 102 ships and 3,722 men returned to England.

Spain Changes Its Plans

The English attack on La Coruña caused great concern. It showed that the enemy could land troops on Spanish soil. Even though the attack failed, several cities felt seriously threatened.

Spain needed to decide what to do to protect its coasts from new English attacks. They also had to make sure the treasure fleets from the Americas arrived safely.

The decision was made to move the entire navy to the port of Ferrol. Its location was perfect for these missions. From then on, Ferrol and Lisbon became the main bases for naval operations. By early 1590, many ships were anchored in Ferrol:

| Galleons of Portugal | 4 |

| Galleons of Castile | 11 |

| Galeasses | 2 |

| Ships of His Majesty | 2 |

| Private vessels | 8 |

| Pataches | 8 |

| Zabras | 10 |

| Faluas | 2 |

The English attacks had such a big impact that Philip II's court even considered wild ideas. One pilot, Juan de Escalante, suggested setting English ships on fire in their own ports.

This tactic, using fire ships, had been very effective during the siege of Antwerp in 1584-1585. The English had also used them against the Spanish Armada in 1588.

Because of these past events and Escalante's reputation, he was given the means to try his plan. Three ships were taken for this purpose. They left in mid-August with Escalante, ready for the mission. But they met English naval ships. Escalante ordered his crews to move to his smaller boat and sink their own ships to avoid capture.

The owners of these ships later asked for money in court because they had lost their only way to make a living.

The English also hoped to destroy the Spanish Armada with a surprise attack. A Spanish prisoner, Francisco de Ledesma, learned during his captivity that twelve Englishmen were planning to set fire to the Armada wherever it was docked.

But apart from these big plans, Spain's strategy was mostly about defending its coasts. Their main goal was to protect the arrival of the fleets from the Americas. They also started thinking about new types of ships that would be better for these kinds of fights.

For example, Don Juan Maldonado wrote to the King in October 1589. He explained the need for ships that could sail long distances, carry cannons, and have enough men to find and attack pirate ships. He said that big ships were too slow to chase pirates, and small ships were not suitable. So, they needed medium-sized ships of 150 to 200 tons that were light and fast.

Fighting in Brittany

These defensive plans were still in place in 1590. Philip II asked his Council of War what the navy in Ferrol should do that year. By the summer of 1590, about 100 ships were ready.

On May 18, 1590, the council said that it was too late in the year and they had too few soldiers and sailors for any major operation. They suggested choosing 15 or 20 large ships and 12 or 15 smaller ships. These ships would carry elite soldiers and patrol the Spanish coasts. Their job would be to clear the seas of pirates and escort the treasure fleets. The other ships would be sent home, and the remaining soldiers would go to garrisons. This would save money and allow the King to wait for a better time to carry out the main invasion plan.

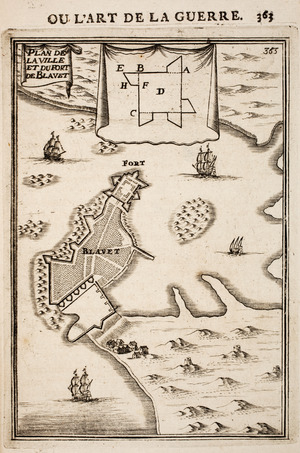

A few weeks later, on July 6, 1590, the War Council learned about a letter from Diego Maldonado in Nantes. He reported that Philippe-Emmanuel de Lorraine, Duke of Mercœur offered the "port of Blavet" to Spain. Mercœur hoped for Spain's help to free him from the "heretics" (Protestants).

The council, which had been hesitant before, was now very excited. They thanked God for opening the port of Blavet to the King. They saw it as a great opportunity to keep Brittany Catholic. They also noted that Blavet was "the most comfortable and important" port for invading England. It was easy to send help there, and Brittany had plenty of supplies.

The next day, the King ordered that help be sent "as soon as possible." He decided to send Don Juan del Águila's entire infantry tercio instead of gathering soldiers from different groups.

This decision might have been made even before Diego Maldonado's letter arrived. On June 1, the King had already ordered Don Juan del Águila to go to Ferrol. He arrived on June 4, though the order to prevent his tercio from sailing was not sent until July 10.

Why Spain Supported the Catholic League

The question of who would be the next king of France was very important to Philip II. He could not risk a Calvinist (Protestant) becoming king of the neighboring country.

In 1584, he had signed the Treaty of Joinville with Henry I, Duke of Guise. In this treaty, Philip promised to strongly support the Catholics. But in late 1588, after the Spanish Armada failed, Henry III of France ordered the assassination of the Duke of Guise and his brother. This led to a public uprising known as the Day of the Barricades, and the Catholic League took control of Paris.

While besieging Paris, the French king was assassinated by Jacques Clément. The conflict between the two sides became very intense. The dead king named Henry (IV) of Navarre, a Calvinist, as his heir. But the Catholic League proclaimed the old Cardinal of Bourbon as king, calling him Charles X.

Philip II felt he had to get involved. He supported the Catholics. After Charles X died, Philip even dreamed of putting his own daughter, Isabella Clara Eugenia, on the French throne.

Spain's commitment to the Catholic cause was clear. In the summer of 1590, Philip ordered Alexander Farnese to go with his troops from Flanders to help the Catholics besieged in Paris. Farnese had a brilliant campaign. He forced Henry IV to stop the siege and left a Spanish garrison in Paris.

Spain also considered sending troops to Languedoc, either from Italy or Spain. An army that "invaded" Aragon was said to be "passing through France." Since 1590, a group of lancers had already been operating there.

The expedition to Brittany was part of this plan to get involved. It aimed to support French Catholics in a strong Catholic area. It also offered the chance to secure ports that would help control communications with Flanders. These ports would also serve as bases for the planned attack on England.

This idea was always in everyone's mind. The Council of War's opinion clearly showed this. For example, on April 12, 1592, Pedro de Zubiaur told the King that the campaign was important for "bringing about the obedience of rebels of Flanders and reducing England, Scotland and Germany to our Holy Catholic Faith." A year later, on May 5, 1593, he again urged the King to provide everything needed for the forces in Brittany. He said it was as important to control that coast as it was to control France, Flanders, Scotland, England, and Germany.

Don Juan del Águila's Tercio

To carry out the plan in Brittany, Spain sent the tercio led by Don Juan del Águila. This was one of three tercios attached to the Armada at the time. When it sailed, it had 15 companies: 14 Spanish and 1 Italian infantry. There were 3,013 soldiers listed as follows:

| Officers & administrators | 123 |

| Pikemen | 1,050 |

| Arquebusiers | 1,465 |

| Musketeers | 375 |

These numbers are lower than some reports, which might have included sailors who were part of the ship crews.

The soldiers' equipment was poor; they lacked armor and helmets. So, they were given some from other tercios before leaving. These shortages, and later problems in Brittany, hurt the soldiers' morale. Many deserted or got sick, reducing their numbers. However, they received reinforcements later. For example, 2,000 men arrived in April 1591, another 2,000 with Martín de Bertendona in September 1592, and 2,000 more from the Army of Aragon in 1593. This helped keep the force at about 3,000 men.

To transport the tercio to Brittany, a squadron of ships was formed. It included 4 galeasses, 2 galleys, and 31 other vessels. Sancho Pardo commanded this fleet. The journey began on September 7, 1590, from Ferrol. It was full of problems due to bad weather, forcing them to return to La Coruña twice. They finally left on September 19.

This terrible journey badly affected the soldiers. When they landed, they looked so broken, thin, and sick that the Breton ladies felt pity and cared for over 600 sick men. However, the locals' opinion changed quickly. They saw these same men fight bravely against the Calvinist troops led by Henri, Duke of Montpensier. The Spanish soldiers, in a disciplined way, managed to lift the siege of Dolo.

How the Campaign Was Fought

The Brittany campaign was special because it involved both land and sea operations. Don Juan del Águila's infantry handled the land battles. A fleet of ships stayed in Blavet, and other Spanish squadrons operated from Spanish ports. The Spanish-controlled areas of Brittany provided support.

Let's look at these two parts separately, focusing on the naval actions.

Land Battles

Spanish troops arrived in Brittany to help the Catholic League forces led by the Duke of Mercœur. After lifting the siege of Dolo, they besieged Hennebont. They used six large cannons from their galleasses to create a big enough hole in the defenses. This forced the town to surrender. The town avoided being looted by paying 20,000 scudi. By the end of 1590, Águila placed soldiers in Vannes, took control of Crevique, and strengthened defenses in places they occupied. Over time, the Spanish troops became very important, and they started acting with some independence. This allowed them to control territory and important ports for Spain, even as the French grew suspicious.

Opposing them were the Prince of Dombes' troops (Huguenots) and, soon after, an English force led by John Norris. Queen Elizabeth I sent the English to support the Prince.

This led to direct fights between the Spanish and English helper troops. The most dramatic example was on May 22, 1592. The Spanish came to help the town of Craon, which was under siege by the Huguenot army, supported by the English and Germans. Águila's tercio was key. They lifted the siege, badly defeating their enemies. The enemy forces ran away, leaving over 1,500 dead and losing all their weapons, ammunition, and supplies.

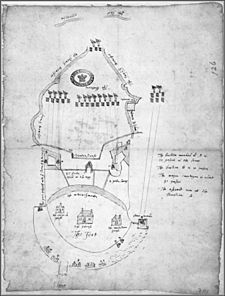

The Spanish usually had the upper hand. They had a strong base in Blavet after building the "Fort del Águila" (Citadel of Port-Louis). Don Juan del Águila's men, with help from galley slaves, built this fort under the engineer Cristóbal de Rojas. Building was very hard. Some days, the galley slaves could not work because they had no food. Doctors said some men died from hunger. Also, some building materials had to come from Spain, like lime from Guipúzcoa, which sometimes arrived in bad condition.

While Blavet remained firmly under Spanish control, other important ports were harder to hold. For example, Don Juan del Águila occupied Saint Malo in 1591 but had to leave it soon after because he didn't have enough troops. This was especially true for the port of Brest, which was a top goal for years. In 1594, they occupied the Quélern peninsula near Brest. Three infantry companies, about 400 men, stayed there under Captain Tomé de Paredes. They quickly built the "Fort of the Lion (El León)". These men fought with amazing courage for several months. But on November 19 of that year, they were defeated by much larger French and English forces. The English were very harsh, killing almost everyone. Only 13 Spaniards survived. The enemy lost 3,000 troops in battle and another 3,000 to disease.

From the start, Spain knew how important it was to have safe ports at the entrance of the English Channel. These ports would help them communicate with Flanders and serve as bases for invading England.

So, when Águila's Tercio was sent in 1590, some of the ships that transported the troops stayed in Blavet. Their job was to help with land operations and control sea traffic in that part of the channel.

Other Spanish squadrons from Spain also helped the permanent fleet in Brittany.

The Permanent Fleet in Brittany

The ships in this fleet changed over time, but it always included pinnaces and round ships (like a Carrack).

At first, two galleasses, three galleys, four barques, two flyboats, and two zabras stayed in Blavet. Captain Perochio Morán commanded them. But the galleasses had trouble operating in those waters, and the galleys were in poor condition. So, four new galleys were sent from Spain under Don Diego Brochero de la Paz y Anaya. He then took command of these forces. Their numbers changed over the years due to losses and new ships being sent.

Logistical Support Squads

Different squadrons from the Ferrol Navy helped the expeditionary force. They sent materials, money, and troops from northern Spain.

Pedro de Zubiaur's Pataches, from Santander and El Pasaje, did most of these missions. They also actively helped the Brittany forces in naval operations in the channel. When money was transported, Juan de Villaviciosa's units escorted them.

The Ferrol Squadron

Larger ships from the Navy were used to send more troops. These ships stayed in Ferrol under the command of Don Alonso de Bazán.

A clever system of convoys and better spy networks helped Spain stop English naval attacks on their treasure fleet in the 1590s. A great example was Bazán's defeat of a squadron of 22 ships led by Lord Thomas Howard in 1591. This happened off the Island of Flores near the Azores. Howard had planned to ambush the treasure fleet. In this battle, the Spanish captured the English flagship, the Revenge, after its captain, Sir Richard Grenville, fought very stubbornly.

In October 1592, 2,000 soldiers were transported aboard 17 ships from Don Martín de Bertendona's squadron. The galleon "San Bernabé," which had captured the English warship the previous year, was among them. This secret and well-executed expedition had a big impact in Brittany. Bertendona noted that it "caused the French great admiration and the Spanish so much happiness." He said that "such large ships had never entered" that port before. The presence of the "San Bernabé" especially drew "many ladies and gentlemen coming to see it."

Besides these diplomatic activities, Bertendona also took the chance to map the port and have pilots explore the entire coast. He found that the port, despite some rocks and banks, could hold many large ships. He stressed its importance for disrupting trade between France, England, and Flanders.

The naval goals of the Brittany campaign were always clear. First, to support land forces in some actions and attack enemy coastal towns. Second, to "make war on England and the rebels of Flanders." They also aimed to capture enemy ships and goods traveling to and from those kingdoms.

But there were disagreements about the best types of ships to use. In Brittany, two different ideas about sea warfare clashed. Brochero believed that galleys could play an important role, even in difficult conditions. He told Philip II that "eight galleys with eight hundred soldiers would be lords of all these ports and the coasts of England."

Pedro de Zubiaur, on the other hand, preferred round ships. He joked that "three galleys are enough... two to go out and the other as a hospital" because of the many sick men caused by bad weather and poor food.

In the end, they decided to use both types of vessels together. Águila thought it was a good idea for galleys to stay near the coast for captures, while barques went out to sea. This way, if enemies tried to escape to land, the galleys would be there. The round ships proved to be much more effective, even in support actions like the relief of Blaye and the attack on Bordeaux.

Five months after Zubiaur's great victory in November 1592, where he used five flyboats to scatter 40 English ships, his naval force defeated an English naval force off Blaye. In the first part of the battle, 4 Spanish pinnaces fought 6 English galleons, scattering them. This allowed Villaviciosa's troops to land and help the Catholic forces. In the final part, 16 Spanish pinnaces and flyboats fought about 60 enemy ships. Both sides had heavy losses, but the Spanish won.

The galleys focused on controlling local shipping and attacking coastal towns. However, problems often arose. Águila pointed out that they sometimes entered "farms that the Catholics have on the land of non-Catholics." He advised them not to bother people on that coast or burn places, because "the soldiers do a lot of damage without getting almost any benefit." Sometimes, there were serious excesses, like when they looted a small Catholic island, burning 15 boats and destroying churches, with some soldiers even taking sacred chalices.

In the early years, these squads were very effective. They captured many enemy ships and greatly reduced sea traffic in the area. This affected both enemy ports and those controlled by the Catholic League. Brochero noted that the Spanish presence was not welcomed by the Catholics because the captures affected their trade. Catholic merchants complained to the Duke of Mercœur, saying that trade restrictions were ruining them. They used their financial support to the League as leverage, arguing that "if they did not have free trade, they couldn't give money to the duke."

In later years, captures decreased. This was because activities were suspended, and enemy ships started sailing in large, well-prepared fleets. For this reason, Zubiaur suggested building 250 or 300-ton galleons. He believed that "half a dozen of them would make a good squadron." Brochero also concluded that to face this new situation, they needed "twelve ships, round and thicker than the present ones, to disrupt the enemy fleets."

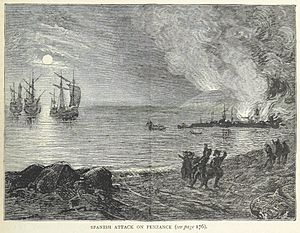

However, galleys continued to be used. They played a big part in the expedition led by Carlos de Amésquita when he landed in Cornwall with 400 troops in August 1595. The Spanish landed in Mount's Bay, then attacked and burned Newlyn, Mousehole, Penzance, and Paul. They also defeated a local militia force led by Francis Godolphin. Another smaller raid on Cawsand bay, also in Cornwall, happened the next year but failed. In June 1596, England sent a second Armada to Spain. They captured Cadiz and held it for two weeks, causing economic losses, but failed to seize the treasure fleet.

The decrease in captured goods and the lack of "open villages to loot or burn" badly affected the maintenance of the Spanish units. Until then, the Court expected them to be maintained from the spoils of their captures.

Shortages became more obvious, and disagreements between commanders grew. Brochero, as head of the permanent squad in Blavet, was under Águila's command. This caused problems due to Águila's personality and their different ideas on how to run operations.

Brochero repeatedly asked the King to be relieved of his post, citing a lack of understanding with Águila. Philip II tried to please both by giving Brochero some independence, as long as they were not working on the same action. This did not satisfy either of them. Águila argued that because he arrived first, he should keep his authority.

Relations between Brochero and Águila were never good, nor were those between Brochero and Pedro de Zubiaur. Zubiaur remained in Brittany under Brochero's authority. Their disagreements mainly arose when it came to sharing the spoils from captured goods. Their letters to the King show their childish reactions. For example, in November 1592, Zubiaur told the King that when Brochero arrived in Blavet with his galleys, "half of the soldiers who served in them left for the countryside." But around the same time, Don Diego reported that "many sailors and two artillery constables and five or six artillerymen have fled from Pedro de Zubiaur's ships." This tension led Zubiaur to ask the King to allow him to serve on his ships without being under Don Diego's command.

What the Campaign Achieved

Spain's control of Brittany clearly affected its conflict with England. This was one of the main reasons for the campaign and why Spain stayed there even when interest in the French throne issue decreased.

Ports like Blavet in Spanish hands were a clear threat to English interests, and the English quickly understood this. From these ports, Spain effectively controlled sea traffic with few losses. They also actively helped Bazán's fleet in bigger operations.

However, due to various problems, the benefits of these strategic positions did not fully happen. In response to the severe blow to Spain from the sacking of Cadiz in 1596, a new expedition against England was planned. But by then, the situation in Brittany had worsened. Also, bad weather again ruined the attempt. In better circumstances, with Blavet's support, the outcome could have been very different.

Finally, the signing of the Peace of Vervins on May 2, 1598, ended Spain's presence on the French coast. Despite countless hardships and sufferings, this campaign wrote one of the most interesting and often forgotten chapters in Spain's Navy history.

See also

- Anglo-Spanish War (1625–30)

- European wars of religion

- French Wars of Religion

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |