English Armada facts for kids

Quick facts for kids English Armada |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Anglo–Spanish War (1585–1604) | |||||||

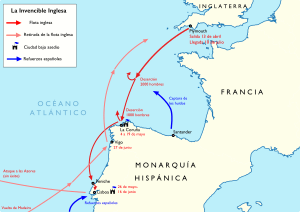

Map of the English Armada campaigns |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

|

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

900 dead or wounded 3 galleons destroyed 13 merchant ships |

||||||

The English Armada, also called the Counter Armada or the Drake–Norris Expedition, was a large fleet of ships sent by Queen Elizabeth I of England to attack Spain. This happened on April 28, 1589, during a war between England and Spain (1585–1604). The English fleet was led by Sir Francis Drake and Sir John Norris. Their goal was to take advantage of Spain's weakness after the Spanish Armada failed the year before. However, the English Armada did not succeed, and Spain won, which helped King Philip II of Spain make his navy strong again.

Contents

Why the English Armada Happened

| Opposing monarchs |

|---|

|

|

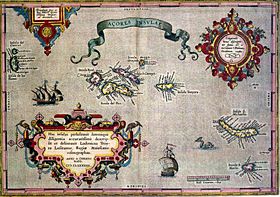

After the Spanish Armada failed to invade England in 1588, Queen Elizabeth I wanted to use this chance to make Spain weaker. She hoped to force King Philip II of Spain to make peace. Her advisers had bigger plans. They wanted to destroy the damaged Spanish fleet that was being repaired in northern Spain. They also planned to land in Lisbon, Portugal, and start a rebellion against King Philip II, who was also King of Portugal. Another goal was to set up a permanent base in the Azores islands. If they succeeded there, they also hoped to capture the Spanish treasure fleet returning from the Americas.

The main reason for this military trip was to stop Spain from controlling trade with the Portuguese Empire. This empire included places like Brazil, the East Indies, and trading posts in India and China. By helping a Portuguese leader, Elizabeth hoped to weaken Spain's power in Europe. She also wanted to open up trade routes to these rich areas. This was a difficult plan because most Portuguese nobles and clergy had accepted Philip as their king in 1581. The person who claimed to be the rightful king of Portugal, António, Prior of Crato, was not very popular. He had failed to set up a government outside Portugal and asked England for help.

There were many problems with this plan. England's fleet was tired and damaged from fighting the Spanish Armada. Also, Queen Elizabeth's money was running low. The English expedition also had too much hope, thinking they could easily repeat Drake's successful attack on Cadiz in 1587. The Queen specifically ordered them to destroy the Spanish fleet in ports like A Coruña and Santander.

Since Elizabeth didn't have enough money, Drake and Norris raised funds for the trip like a business. They got about £80,000. The Queen paid a quarter, the Dutch paid an eighth, and nobles, merchants, and guilds paid the rest. Bad weather and problems with supplies delayed the fleet's departure. The Dutch didn't send the warships they promised. A third of the food was already eaten. The number of volunteers grew from 10,000 to over 20,000 soldiers. Unlike the Spanish Armada, the English fleet also lacked important siege cannons and cavalry (soldiers on horseback). This would make their goals harder to achieve.

The Attack Begins

Getting the Attack Force Ready

Ships for the Expedition

On April 8, 1589, a list showed that the English Armada had about 180 ships. These included royal warships called galleons, English armed merchant ships, Dutch flyboats, and smaller pinnaces. The ships were used for:

| Troops and mariners | 115 |

| Baggage | 33 |

| Horses | 10 |

| Victuals (food) | 10 |

| Munitions (weapons/ammo) | 2 |

| Support | 3 |

| Pioneers (engineers) | 7 |

Another list from April 9 named 84 ships divided into five groups. Each group had about 15 flyboats, making a total of around 160 ships. However, 13 more ships were named later that were not flyboats. So, the total number of ships was at least 173. Since the expedition was largely a business venture, and ships were added until the last minute, the exact number is hard to know. Some reports suggest it could have been close to 200 ships.

The Men of the Armada

On April 8, 1589, two different numbers were recorded for the men on the expedition. Many historians use 23,375, but a closer look at the document shows the number increased to 27,667. This higher number was confirmed by important leaders like Drake, Norris, and Lord Burghley.

A famous story from this time is about Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex. He was only 21 years old and joined the expedition against Queen Elizabeth's direct orders. He hid on a ship called the Swiftsure. Drake and Norris did not tell anyone he was there when the Queen's messenger came looking for him. The Swiftsure sailed away quickly. A strong wind forced it to Falmouth, so no one knew where it was. The main English fleet sailed without the Swiftsure, which joined them later near the Portuguese coast.

Attack on Coruña

After the Spanish Armada failed in 1588, many of Spain's warships were damaged. They were being repaired in ports like Santander and were easy targets. Queen Elizabeth had ordered Drake and Norris to attack Santander first to destroy these ships. But Drake chose to ignore these orders. He said the winds were bad and it was too risky. Instead, he decided to attack A Coruña in Galicia.

It's not clear why Drake changed his mind. He might have wanted to set up a base there or simply raid the city for treasure. Since the expedition was funded by private investors, getting treasure was important. This decision was the first big mistake of the campaign.

While crossing the Bay of Biscay, about 25 ships with 3,000 men left the fleet. Many of these were Dutch ships that returned to England or went to La Rochelle. Coruña was almost defenseless when the English attacked. The city had only a few ships and about 1,200 soldiers, most of whom were not well-trained. The city also had old medieval walls.

The English arrived at Coruña on May 4. Norris's troops took the lower part of the town, killing 500 people and stealing wine and fish. Drake destroyed some Spanish ships in the harbor. The Spanish set one of their own damaged galleons on fire after removing its cannons to use against the English. For the next two weeks, the English tried to capture the upper, fortified part of Coruña. Norris's troops attacked the walls three times and tried to use mines. But the Spanish soldiers, local people, and even women like Maria Pita fought back bravely. They forced the English to retreat with heavy losses.

The English lost four captains, three large ships, and over 1,500 men in the fighting. After two weeks of trying to capture this "simple" fishing town of 4,000 people, Drake left without even getting supplies. He had greatly outnumbered the defenders, but failed. Next, the fleet headed for Portugal, where they met up with the Earl of Essex and the Swiftsure.

Campaign in Portugal

Spain had been busy strengthening the forts around the entrance to the Tagus River, which leads to Lisbon. These forts were ready by May 20. The Spanish leader in Portugal, Archduke Albert VII, ordered local men to be recruited to defend against the English.

Drake's fleet struggled with bad winds after leaving Coruña. It wasn't until May 24 that most of the fleet reached Cape Finisterre. There, they met up with Essex and the Swiftsure. With good winds, they headed for Lisbon. The next day, they saw Cape Roca, meaning the Tagus River was close. By the end of May 25, the fleet anchored in Peniche bay, where they held a meeting.

Queen Elizabeth's plan was to make the Portuguese people rebel against King Philip II. The Portuguese nobles had accepted Philip as their king in 1580. The English supported António, Prior of Crato, who claimed to be the rightful king. But he wasn't very popular and didn't have much support. Despite this, Elizabeth hoped to weaken Spain and gain a military base in the Azores to control trade routes to the New World.

Drake and Norris disagreed on how to achieve their goal in Portugal. Drake had a history of success against the Spanish, but the fleet went with Norris's plan. They decided to land in Peniche and march 70 km (43 miles) south to attack Lisbon by land. Drake would attack from the sea. This was the fleet's second major mistake.

Landing at Peniche

On May 26, Drake arrived at Peniche. The local commander, Ataíde, had about 400 soldiers ready. The English, led by the Earl of Essex, used 32 barges to land on Consolação beach. This beach was dangerous, with rocks and deep water. Fourteen barges sank, and 80 men drowned. But the English managed to land. The first fight happened there, with Captain Benavides and his 100 men fighting 2,000 English invaders. Ataíde led three strong attacks before retreating.

The English landed 12,000 men in just a few hours. They offered terms of surrender to the commander of Peniche's fortress, Captain Araújo. He only surrendered to Dom António, the Portuguese claimant. That same day, Archduke Albert ordered more Spanish galleys and soldiers to São Julião. During the night, many of the men Ataíde had recruited deserted.

The Spanish were worried about their Portuguese allies. The Portuguese were not eager to fight the English. Dom António was not well-liked. He had wasted the Portuguese crown jewels and promised Elizabeth control of the Portuguese empire. The Portuguese people did not rise up to support Dom António as he had promised. The next morning, Spanish cavalry attacked the English, capturing some prisoners.

Norris's March to Lisbon

Norris left 500 men and six ships in Peniche. On May 28, the English army began its long march to Lisbon. They had no cannons or baggage, which made getting supplies difficult. Dom António had promised that locals would provide food. The English had strict orders not to bother the people, but stealing and looting became common outside Peniche. Norris ordered his officers to hang anyone caught stealing.

As they neared Torres Vedras, the Spanish forces retreated. Dom António made a grand entry into Torres Vedras on May 29, with many people cheering. But the English leaders noticed that the Portuguese nobles were missing. These nobles were supposed to lead the people in supporting Dom António. The English pressed Dom António for supplies. He sent soldiers to find a lawyer, Gaspar Campello, to organize food. But Campello had no success because the local people were leaving with their belongings. In Lisbon, people were also fleeing, leaving the city's defense to the Spanish.

On May 30, Drake reached the port of Cascais and anchored his fleet near its forts. He also sent ships to search for enemy vessels. Meanwhile, the English army, constantly attacked by the Spanish, reached Loures, about 10 km (6 miles) from Lisbon. The English were getting hungrier. They didn't know that huge amounts of supplies were just outside the city walls. The Archduke ordered Captain Don Juan de Torres to keep the English busy on May 31. This would give time to bring supplies into the city. If de Torres could hurt the English, even better.

The Spanish tried to make the English come out and fight, but they stayed in their trenches. The Spanish also burned any remaining supplies outside the city. Since the English wouldn't come out, a group of 200 elite Spanish soldiers attacked their camp at dawn on June 1. They shouted, "Long live Dom António!" They killed guards and soldiers sleeping in their tents before the alarm was raised. The English quickly formed a defense, but many were killed. The Spanish retreated with few losses.

While the English rested and starved, the Archduke held a war council. The Portuguese commanders decided to bring their army inside the city walls. They knew the walls were strong, and they could get supplies from the Tagus River. The English were suffering from hunger and sickness. By the end of June 1, the English were in Alvalade, less than an hour away from Lisbon.

High above Lisbon was the strong Castle of São Jorge. It had new, powerful cannons pointing towards the English camp. On June 2, as the English army approached, the cannons fired, surprising them and causing casualties. The English quickly found a route with better cover. Meanwhile, the Spanish burned houses near the city walls to create a barrier. Bazán was ordered to bring 12 galleys to the city. The English camped in a suburb protected from the castle's artillery. A Spanish attack during the night caused more English casualties.

The English tried to find a way into the city. One Portuguese noble loyal to Dom António tried to get permission to use a monastery built against a weak part of the wall. But the monks told the Spanish, and the noble was arrested. Another plan involved a captain betraying one of the gates, but nothing came of it. The least likely plan was that the people of Lisbon would rebel when Dom António reached the walls. None of these plans worked.

Attack on Lisbon

At dawn on June 3, the English prepared to attack the western side of the city wall. The Spanish placed skilled shooters on church rooftops and burned houses outside the Santa Catalina gate to prevent the English from using them to climb the wall. The English then moved south towards the sea, where the Spanish galleys were ready to fire on them.

When Norris finally saw the huge size of Lisbon, he realized his army had no cannons to break through the walls. They also had no ladders or other equipment for a siege. His army was getting smaller by the hour, and the soldiers were weak from hunger. The Portuguese uprising that Dom António had promised never happened. Norris sadly admitted that the campaign was a failure. Their only choice was to defend themselves and retreat to their trenches. At this point, the Spanish went on the attack.

The Spanish launched three attacks at once: one on the trenches in the suburbs, one on the English rear-guard, and cannon fire from São Jorge Castle. The English lost hundreds of men, while the Spanish lost only 25. The Spanish were expecting thousands of reinforcements and were constantly getting supplies by river. The English were running out of gunpowder. On June 4, the English buried their dead and planned a secret retreat to Cascais during the night. To trick the Spanish, they lit many campfires to make it seem like they were still there. The main army quietly left on a route away from the water and main roads. The Archduke, however, suspected something was wrong. He ordered 2,000 lit match cords to be sent on small boats towards the English camp at midnight. This was meant to make the English think they were about to be attacked. It was a lucky coincidence that this trick made the English panic and retreat in a hurry.

Retreat to Cascais

At dawn on June 5, Spanish galleys saw the English moving and opened fire, waking Lisbon. Once the Spanish realized the English were truly retreating, they chased them. The galleys fired on the English infantry. As the English neared Cascais, Spanish cavalry attacked, causing hundreds more casualties. The English lost about 500 men during their march from Lisbon to Cascais.

On June 6, Count Fuentes gathered an army in Lisbon to march on Cascais and inflict more losses. They spent the night in Oeiras. On the morning of June 7, they reached the English trenches but were met with cannon fire from Drake's fleet. The Spanish decided it was too hard to attack the English directly. On their way back to Lisbon, Fuentes met with Bazán. They agreed to keep the English trapped in Cascais, effectively besieging them.

On June 8, the Earl of Essex, eager for glory, sent a trumpeter to the Spanish. He challenged them to an open battle, saying the English had not fled from Lisbon. The Spanish received the messenger politely but sent him back without opening the message. Soon after, the important Portuguese nobleman Dom Teodósio II arrived in Lisbon with 20 nobles, 70 guards, 200 lancers, and 1,000 infantrymen. His arrival not only brought more soldiers but also showed strong support for the Catholic union, making Dom António look like a mere fugitive.

While anchored in Cascais, Drake captured several ships carrying wheat, giving him a large supply of food. They used nearby mills to grind the wheat into flour for bread. On June 9, Fuentes sent soldiers to destroy these mills, making the wheat useless for bread. The English had to boil the wheat to eat it. On June 10, a Spanish officer counted 147 enemy ships anchored at Cascais. He noted that despite good weather, the English hadn't attacked the river entrance, suggesting they wouldn't.

Then, on June 11, the commander of Cascais castle, Captain Francisco de Cárdenas, was visited by two Franciscan monks. They falsely told him that Lisbon had surrendered to Dom António and that fighting was pointless. Cárdenas had not heard from Lisbon in days, so he believed them. He surrendered the castle without a fight, getting good terms for his men. Inside the castle were plenty of supplies, ammunition, and 14 cannons. When Cárdenas arrived in Setúbal, he was arrested and executed for surrendering.

Each day, the Spanish-Portuguese army grew stronger, while the English army shrank. The Spanish in Lisbon still expected a combined land and sea attack on June 13, St. Anthony's feast day. The Count of Villadorta and the Duke of Bragança joined forces to complete the siege by land. Meanwhile, Martín Padilla arrived with 15 galleys, completing the siege by sea. The English finished loading their ships that very night.

Sailing Out to Sea

On June 16, everything was ready for a major Spanish attack on the English, but bad weather delayed it. That day, two small ships arrived from England with letters from the Queen. They also brought news that 17 supply ships were on their way, but no new troops. Many of these supply ships had left the fleet earlier. The Queen's letters ordered her favorite, Essex, to return immediately. She strongly criticized Drake and Norris for how badly they had managed the expedition, especially for not going to Santander to destroy the Spanish Armada's remains.

Drake wanted to leave Portugal quickly and achieve some kind of victory, but the wind was not cooperating. On June 18, despite the bad wind, Drake finally decided to sail away from the coast with his fleet and the captured merchant ships, totaling about 210 vessels. Essex then escorted about 30 Dutch merchant ships, which left the expedition. To please the Queen, Drake decided to try and capture the treasure fleet in the Azores. But the winds pushed him south-southwest, keeping him in sight of the Portuguese coast. Meanwhile, the Spanish troops who arrived in Cascais after the English left found the town in ruins. Part of the castle was blown up, the town was looted, and churches were damaged.

The Spanish fleet, led by the Adelantado (a high-ranking military governor), set off in pursuit of the English Armada on June 19. The first sea battle happened on the morning of June 20. The English lost 9-11 ships and two smaller boats, and their fleet was scattered. By the end of the day, Drake had managed to gather most of his fleet again. Some English ships were separated by a storm and ended up near the Madeira islands. They took over Porto Santo and resupplied themselves. Unable to find the rest of the fleet, they sailed for England.

English prisoners captured by the Spanish after the June 20 battle revealed that the fleet had no supplies. This made a trip to the Azores unlikely. So, the Spanish focused on the 500 men Norris had left at Peniche on May 28. Drake tried to sail back up the Portuguese coast against the wind to pick up these men. But Spanish cavalry arrived on June 22 and attacked the garrison as they tried to board a small ship, killing or capturing about 300. Drake arrived at Peniche the next day, hoping to pick up the remaining men, but the fortress fired cannons at him. He sailed away. On June 24, a favorable northeast wind came up, and Drake set off for the open sea, seemingly heading for the Azores.

Attack on Vigo

Drake struggled against the wind for five days, finally reaching the small, undefended fishing town of Vigo on the morning of June 29. By nightfall, about 133 ships had anchored near Vigo. Since it was too late to land, they waited until the next morning. This gave the Spanish time to evacuate the town. The Spanish expected the English to enter as a group, but then spread out to loot, where ambushes waited.

At dawn on June 30, the English landed about 2,000 men at three different spots. They were shocked and disappointed to find the town completely empty. Angry about their defeats in Coruña and Lisbon, they showed no mercy to Vigo. They used their cannons to destroy the town, then burned churches and set the rest of the town on fire. This destruction made them overconfident. They spread out to search for food and loot. There were some small fights, and a few hundred English invaders were killed. The main reason for landing was to refill their water barrels, which they did during the chaos.

The next day, July 1, Don Luis Sarmiento arrived with a large Spanish force. They surprised the English, killing hundreds and capturing prisoners. Drake quickly ordered his men back to the ships. He sent a message promising to leave if the prisoners were returned. When the Spanish commander saw how much damage had been done, he had the prisoners executed in front of the English fleet. He challenged Drake to send more Englishmen so he could execute them all. The next morning, Drake sailed out of the area with most of his fleet. Norris was left behind with about 30 ships because he was further up the waterway and couldn't leave before a storm hit. Two of Drake's ships were captured that day, and two more were destroyed on rocks. On July 3, Drake still struggled against the wind towards Finisterre. Norris, still near the Cíes Islands, removed cannons from a damaged ship and burned it. Norris was able to leave on July 4.

Returning to England

Spain saw the last of the English fleet on July 5 as it struggled past Finisterre against the wind. Captain Diego de Aramburu was sent from Santander with a small fleet of zabras (small ships) to chase the English fleet almost all the way back to England.

From this point, it's hard to know exactly what happened to the whole English Armada, but the information available is very sad. Thomas Fenner's ship, the Dreadnought, started with nearly 300 sailors but returned to Plymouth with only 18 healthy men. The rest were dead or sick, including Fenner himself. On another ship, the Griffin of Lübeck, only 5 or 6 men were well enough to work, but they were too weak to raise the sails. The rest were dead or diseased. Drake's main ship, the Revenge, had a leak from storm damage and almost sank as it led the remaining fleet home to Plymouth, arriving on July 10.

What Happened After the Armada

Norris landed in Plymouth on July 13. He immediately worked with the Earl of Essex and Anthony Ashley to hide how bad the disaster was. They even tried to make it sound like a great victory. The next day, Norris sent a letter to Walsingham admitting failure but involving him in the cover-up. On July 17, Queen Elizabeth replied to the false reports, saying she was happy with the "happy success" of the expedition.

After Norris's first report, a lot of propaganda was spread. A detailed account, written by an "anonymous" participant, was published in 1589. It tried to make the participants look good, but it couldn't hide the complete failure of the campaign. Later, a historian noted that they wrote from Cascais to make everything sound as good as possible. However, this English story was very effective at hiding the true scale of the disaster. Rarely had the English government been so poorly informed.

A bad result of this misinformation was the rapid spread of disease. The returning sailors brought illnesses to the port towns in England. Since the Queen's people were told the expedition was a success, the ships docked without being checked. In Plymouth alone, 400 local people died within the first few weeks. Lord Burleigh issued an order that no one from the expedition could enter London, or they would face death.

None of the expedition's goals were achieved. For many years, this failure discouraged such large-scale private military ventures. The English force lost many ships, soldiers, and resources but did not seriously harm the Spanish forces. Since it was a business venture, it was also a financial failure. They only brought back 150 captured cannons and £30,000 worth of stolen goods. The financial problems were solved by simply not paying the survivors.

Drake and Norris were never publicly punished after a full investigation. However, they both lost the Queen's favor. Norris did not get another command until 1591, and Drake waited until 1595 for his next, and final, voyage. Despite all this, the Queen never changed her triumphant letter from July 7, 1589.

Even though 25 ships with 3,000 men left the expedition, 17 of them later returned. In total, as many as 40 English ships were sunk, destroyed, captured, or went missing during the campaign. Fourteen ships were lost directly to Spanish naval forces: three at Coruña, six sunk by galleys near Lisbon, and three captured by another galley squadron near Lisbon. Two more were captured by Spanish ships near England. A 2021 study claims to have found the remains of five English ships from Drake's fleet in Coruña harbor. The rest were lost to storms as the fleet returned, chased by Spanish ships. Many English ships arrived in Britain with very few crew members, as many had died from hunger and disease.

It's very difficult to know the exact number of men and ships lost because the reports vary so much. Of the 3,722 men who returned and asked for pay, only 1,042 received it. Of the thousands of widows, only 119 received their husband's pay. If 27,667 men started, and only 3,722 came back, that means nearly 24,000 died, deserted, or are missing. Some reports say between 11,000 and 18,000 died, while only 3,000 to 5,000 survived. Even if 23,375 men embarked and 5,000 survived, that's still over 18,000 dead.

Counting the lost ships is also hard. Starting with 180 documented ships, the total could have been around 200. A pay list from September 5, 1589, named 102 ships. Of the 84 ships that sailed on April 9, only 69 appeared on the September 5 list, meaning 15 ships were lost. But many more ships not on these lists also failed to return. In addition to the 69 known to have returned, another 33 medium-sized ships also came back.

Regardless, England missed a chance to strike a decisive blow against the weakened Spanish Navy. King Philip was able to rebuild his navy the very next year. Spain remained the most powerful country in Europe for several decades. The failure of the English Armada drained England's treasury, which Queen Elizabeth I had carefully built up. The failure was so embarrassing that England still downplays its importance. The war was very expensive for both sides. Spain, fighting France and the Dutch at the same time, had to stop paying its debts in 1596 after the English Capture of Cádiz. After a successful raid on Cornwall in 1595, Spain sent three more armadas: in 1596 (scattered by a storm), 1597 (7 ships landed 700 soldiers), and 1601 (33 ships, held Kinsale for three months). But these efforts ultimately failed.

Peace was finally agreed upon with the signing of the Treaty of London in 1604.

What We Learn from the English Armada

The failure of the English Armada was so embarrassing that, even today, England barely talks about it. As David Keys explained:

The English Armada was larger than the Spanish, and from many points of view it was an even greater disaster. This fact, however, is completely overlooked. It is never mentioned in the history courses taught in British schools and a majority of British history teachers have never even heard of it.

Images for kids

See Also

In Spanish: Invencible Inglesa para niños

In Spanish: Invencible Inglesa para niños

- Spanish Armada in Ireland

- Brittany Campaign

- Raid on Mounts Bay

- Attack on Cawsand

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |