3rd Spanish Armada facts for kids

Quick facts for kids 3rd Spanish Armada |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Anglo-Spanish War | |||||||

Falmouth at the time of invasion |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Fleet: 44 galleons 16 merchant galleons 52 hulks 24 small craft Troops 9,634 soldiers 4,000 sailors Total: 140 ships 13,000- 14,000 men |

Fleet: 12 ships rising to 120 ships (23 October) Troops: 500 (October) rising to 8,000 (November) |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 6 ships captured, 400 captured Storms 22 ships sunk or destroyed 1,000 dead Total: 28 ships, 1,500 killed or captured |

1 bark sunk Low |

||||||

The 3rd Spanish Armada, also known as the Spanish Armada of 1597, was a big naval event. It happened between October 18 and November 15, 1597. This was during the Anglo-Spanish War between England and Spain.

King Philip II of Spain ordered this attack. It was Spain's third try to invade or raid the British Isles. Philip wanted revenge because England had attacked Cadiz the year before. The previous Spanish Armada had failed due to a big storm.

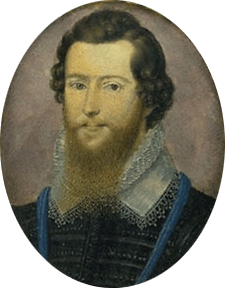

This new Armada was led by Martín de Padilla. He hoped to stop the English fleet, led by Robert Devereux, as it returned from a failed trip to the Azores. After that, the Armada planned to capture an important port like Falmouth or Milford Haven. These ports would then be used as bases for a full invasion.

However, when the Spanish ships reached the English Channel, a storm scattered them. Some ships still managed to push on and even landed soldiers on the English and Welsh coasts. The English fleet, also spread out by the same storm, didn't know the Spanish were there. They arrived safely back in England, losing only one ship.

Padilla eventually ordered his fleet to retreat back to Spain. The returning English ships captured some Spanish vessels. From these, they learned important information about the Armada. This caused panic in England, especially since the English coast was mostly unprotected while their fleet was at sea.

The relationship between Queen Elizabeth I of England and the Earl of Essex got worse. Charles Howard took over as commander of the English fleet. Howard immediately sent his ships to hunt for the Spanish. Most Spanish ships had already returned home. Any remaining Spanish ships were captured, along with their soldiers and crew. Philip II was blamed for the failure by his commanders. This Armada was the last one of its kind that Spain would launch under King Philip II.

Contents

Why the Armada Sailed

The war between Spain and England had been going on for almost twelve years. Neither side had achieved much. King Philip II of Spain had supported the Catholic League in the religious war in France. This meant Spain had military bases along the French and Flemish coasts. These bases were very important because they allowed Spain to threaten England with its fleet and soldiers.

England also got involved in France, but they supported King Henry IV of France. In 1596, the Spanish captured Calais. This made an invasion of England seem more possible. To stop France from making peace with Spain, England signed the Triple Alliance with the Dutch Republic and France.

The next year, England sent a fleet under the Earl of Essex and Charles Howard to Cadiz. They captured and looted the city. King Philip was very angry about this. He immediately started planning how to defend Spain.

After the defeat at Cadiz, Philip II wanted revenge. He ordered a large Armada to attack England. The plan was to take the French port of Brest. But just after they set off, the fleet was destroyed by autumn storms near Cape Finisterre. Spain lost many ships, soldiers, supplies, and money. It was a huge disaster.

Even though his country was facing financial problems, King Philip ordered another invasion. The defeat at Cadiz, the failure of the previous Armada, and the wars in France and the Netherlands caused Spain to go bankrupt for the third time during Philip's rule. There was also a bad harvest, which made things even worse for many people. Despite all these problems, the fleet was gathered, and men were forced into service. Spain relied heavily on its Italian lands for ships, money, and supplies to make up for the losses.

Building the Armada

Pedro Lopez de Soto, a secretary for the Spanish commander, estimated the size of the fleet. It was huge in terms of men, ships, and supplies. The first idea was to attack Ireland to help rebels there. But the main Spanish commanders wanted to attack England instead.

King Philip decided to attack Brest to draw English troops away from other areas. However, news arrived that the English fleet, led by Essex, was sailing near Spain and then around the Azores. They were trying to capture Spanish treasure ships. This news shocked the Spanish court. Philip was so determined to get revenge that he rushed the attack, even if it meant less preparation.

The fleet gathered at A Coruña. It was commanded by Juan del Aguila and Martín de Padilla. The plan had changed from Ireland to attacking Falmouth in Cornwall. The Spanish wanted to hold Falmouth as a base. They hoped this would force Queen Elizabeth to make peace. They also hoped that English Catholics would join them.

This invasion was planned to be much larger than the 1588 attempt. Troopships would take Falmouth, while warships would stop Essex's fleet returning from the Azores. Another target, as a backup plan, was Milford Haven in Wales. This was a good landing spot, where Henry VII had landed his men long ago. A Spanish observer noted that many Catholics in Milford Haven were against the English.

The true goals of the Armada were kept secret from most captains and officers. They didn't know if it was an invasion, a raid, or just a naval attack. This was to prevent spies from finding out. The full plan would only be revealed when they got close to the English Channel.

Taking and holding Falmouth or Milford Haven was a strategy for Spain. It was revenge for England capturing Cadiz. These captured places would be used to force English troops out of France and the Netherlands. If England refused, the bases would be used to attack English and Dutch trade ships.

In total, 108 ships were at A Coruña. More ships would join from other ports. By October 1, the fleet had 136 ships. This included 44 royal galleons, 16 merchant ships, and 52 large supply ships called hulks. There were also 24 smaller ships. The fleet carried 8,634 soldiers and 4,000 sailors, making a total of 12,634 men. There were also 300 horses. Among the soldiers were elite Spanish units called tercios. Many of these soldiers were from Spain's lands in Italy, like Naples and Lombardy. They were known for rarely losing battles.

The Spanish Armada of 1597, even though it wasn't fully ready, left A Coruña on October 18.

The Attack Begins

The Armada left La Coruña and Ferrol. A fleet under Admiral Diego Brochero was supposed to meet another fleet from Blavet in Brittany. This second fleet had a thousand men led by Pedro de Zubiaur. Zubiaur joined them for a meeting to decide the final details of the landing.

After three days of good weather, the fleet reached the Channel. They sailed towards the English coast without anyone stopping them. As they sailed, they found and sank an English ship, taking its crew prisoner.

The Storm Hits

Then, everything changed. The weather got bad. An easterly wind turned into a strong gale, and the storm lasted for a few days. This time, however, the results were not as terrible as in 1588. The Spanish ships were better at communicating with each other.

At first, the commander, Padilla, tried to wait out the storm. He hoped the weather would get better. But the next morning, the winds got even stronger. The storm blew for three days, and Spain lost more ships. The San Lucas ran aground near the Lizard, losing its horses and mules. A galleon carrying Don Pedro Guevera, a general, caught fire and exploded. It was never seen again. Another large ship with siege equipment and flammable materials also exploded. It took a French ship full of soldiers with it.

Only one large galleon, the San Bartolomé, sank when it hit rocks near the Isles of Scilly. Admiral Brochero's ship, the San Pedro, was badly damaged. He had to go to a port to fix it. But he quickly got on a smaller ship and rejoined the Armada. He tried to gather the ships for one last attempt to land at Milford Haven, Waterford, Cork, or Brest. On the night of October 25, he saw that the strong currents wouldn't stop. He sadly ordered the remaining ships to scatter and look out for their own safety.

Spanish Ships Land and are Captured

One Spanish ship, damaged by the storm, was captured near the Scilly Isles by an English ship. Even though it sank on its way to Penzance, the prisoners were taken to Falmouth. The English captain reported that the Spanish fleet was about thirty leagues (around 90 miles) from the Scilly Isles. The Spanish prisoners also had letters and plans about meeting at Falmouth. This was the first sign that the Armada was near Cornwall. The English government immediately met to discuss it.

However, evidence from just one ship was not enough. Also, the main English fleet had not yet returned. They could only send orders and supplies to their fleet, hoping it would come back in time. A few English ships in the area were sent out. Queen Elizabeth's cousin, the Earl of Ormond, was put in charge of all military forces in Ireland. This was in case Spanish ships landed there. Queen Elizabeth herself learned about the Spanish fleet on October 26.

The storm badly affected the Spanish fleet. Several ships were swept far north of Cornwall, towards the Welsh coast. Three Spanish ships came near Pembrokeshire and headed for Milford Haven, their second target. A small Spanish ship, the Nuestra Senora Buenviage, was driven ashore by the storm in Milford Haven. It was captured and looted. It had gold and silver on board, and Welsh soldiers fought over it.

Another ship, the Bear of Amsterdam, was beached near Aberdyfi on October 26. It had missed Milford Haven and sailed into the Dyfi Estuary by mistake. Spanish soldiers landed ashore but were attacked by the local militia. They lost two men and had four captured. They went back to their ship but couldn't leave because there was no wind. Near Caldey Island, a Spanish treasure ship ran aground. But local disorder allowed the ship to escape.

In Cornwall, a Spanish force landed 700 elite soldiers on a beach near the Helford River close to Falmouth. They dug in, waiting for more soldiers. English militia (local soldiers) started to arrive in large numbers, but they were not well-armed. The Spanish fleet was still scattered. With no hope of more soldiers, the Spanish got back on their ships in the dark, after only two days ashore.

England Gets Ready

The rumors caused confusion, and Plymouth and the surrounding area were put on high alert. Sir Ferdinand Gorges, the Governor of the Fort at Plymouth, put 500 men on guard. A small ship was sent out to report any sightings of the Spanish fleet. Gorges received reports of Spanish landings in Cornwall and Wales. He immediately sent this information to the government and the Queen in London.

Panic spread across much of England and Wales. Troops were called back from Amiens in France, which had just been captured by English and French forces. Soldiers in the West Country were also prepared for battle. Charles Blount was put in charge of the English land forces. A few English warships were sent to the coasts of Cornwall and Devon. Although they were also scattered by a storm, they reached Falmouth a few days later. But they didn't see any Spanish ships.

At the same time, some Spanish ships were still off the coast of England. They were confused and couldn't find a safe harbor. Eventually, with the wind behind them, Admiral Brochero ordered them to head back to Spain. They sailed back to A Coruña in disorder.

The English Fleet Returns

On October 23, the day after the Spanish had scattered, the first English ships started to return. They arrived in Falmouth, Plymouth, and Dartmouth. Amazingly, they had completely missed the retreating Spanish fleet. At one point, both fleets were sailing towards each other.

When Essex arrived, he learned about the situation from Mountjoy. Both were surprised that the English fleet had missed the Spanish. Essex immediately wrote letters to the government and the Queen to try and fix things. At first, the Queen gave him full power. The ships in the English Channel were ordered to join him. The government was impressed by his understanding of the Spanish plan to capture Falmouth or Milford Haven, or to stop the English fleet.

However, soon after, the Queen sent him a sharp letter. She criticized him for failing in the Azores and for leaving England unprotected. Essex immediately went to the royal court to explain himself. But he was met with cold disapproval from the Queen. He then went home, feeling miserable. In Essex's absence, Howard of Effingham was given command of the fleet to deal with the threat.

A few days later, the rest of the English fleet arrived. This included Vice Admiral Sir Walter Raleigh in the galleon Warspite. His ship was swept around to St Ives. The Warspite was heading into port for repairs when it spotted a Spanish ship and a smaller vessel. Raleigh's commander, Sir Arthur Gorges, stopped them. After a short fight, he captured both ships, along with their soldiers and crew. He took them to St Ives.

Juan Triego, the captain of the smaller Spanish ship, was questioned by Gorges and Raleigh. He was forced to reveal Spanish plans and troop positions. They also learned that the Spanish had gathered information about the English coast a year earlier. The captain of the other Spanish ship, Perez, confirmed the same information. All the other captured officers and captains from St Ives and Milford Haven were also questioned. Detailed information about the size and organization of the Spanish fleet was finally understood. The Spanish fleet had come as close as ten leagues (about 30 miles) from The Lizard. The danger was still very real. English ships returning from the Azores had seen Spanish ships, though from a distance.

Hunting the Spanish

Raleigh, who had been made a Lieutenant General, traveled from St Ives to join Howard in Plymouth. They quickly sent a small fleet to chase the Spanish. Many of the crew were tired from the trip to the Azores. Mountjoy took command on land, organizing the soldiers and local militia in Plymouth. He would soon get more troops from the Netherlands.

By the time the English fleet set sail, the first Spanish ships had already safely reached A Coruña. But the English didn't know this. The English ships searched as far as the Bay of Biscay. They even went to ports in western France, looking for any sign of Spanish ships.

On October 30, an English warship under Captain Bowden captured a Spanish ship near Cape Finisterre. This captured ship was a small, fast vessel carrying an army captain and 40 soldiers, plus sailors. Captain Bowden had boarded and taken it with only 28 men and boys. The Spanish captain and officers were questioned again. They gave the same information about the Spanish invasion. But this time, the captain said he had only seen one other Spanish ship, heading about 30 leagues (90 miles) towards the coast of Spain.

More proof of the Spanish retreat came from Sir George Carew. After a storm pushed his ships further south, he saw and chased eleven ships flying the Spanish flag. They were rushing back to Spain. The Spanish ships were too far ahead to be caught. So, Carew joined Howard with the main fleet to share the news. These two reports meant that the invasion was effectively over. Howard and Raleigh sent the fleet back to Plymouth to report the news to the government and the Queen.

The End of the Armada

The only Spanish ship left in the area from the Armada was the Bear of Amsterdam. It was still at Aberdyfi. For ten days, because there was no wind, the local militia couldn't board the Bear of Amsterdam. An attempt to burn the ship failed because of the wind. The Bear of Amsterdam eventually left. It was driven around the Cornish coast and swept up the Channel by an easterly gale, getting some damage.

Hoping to find the Spanish fleet already at Falmouth, the ship was captured not far from there on November 10. It was caught by an English squadron waiting for it. The ship was taken to Dartmouth with 70 Spanish prisoners. This was the last ship from the Armada to be captured.

What Happened Next

By mid-November, it was clear that the Spanish Armada invasion had failed. Some broken pieces of Spanish ships were washing ashore on the English coast. The English fleet, local militias, and troops were kept ready. But soon, everyone realized the danger had passed. So, they were sent home for the winter. Troops who had come from other countries either went back to Holland or France.

In total, seven Spanish ships and about 15 other vessels sank. Six Spanish ships from the Armada were captured by the English in the South West of England and West Wales. Only one large Spanish galleon was lost. A large merchant ship was captured by the French, and its 300 crew members were imprisoned. In all, between 1,500 and 2,000 Spanish soldiers, sailors, and civilians were lost, captured, or got sick.

A count on November 21 showed 108 Spanish ships at A Coruña. Many needed repairs, and the whole fleet needed new supplies. With these losses, the failed campaign meant no more attacks could be tried that year. Also, the English Catholics did not rebel, even when they knew the Spanish fleet was offshore. In fact, many even said they would fight against the Spanish.

According to the Spanish commanders, King Philip trusted God more than good preparation. Padilla was so angry about the lack of preparation that he told the Spanish King:

If your majesty decides on an attempt on England, take care to make preparations in good quantity and in good time and if not then it is better to make peace.

The Spanish king was very upset by the news. He knew a third Armada attack was not possible. He then became ill and shut himself away in his palace. Bonfires and parades were held across Spain, hoping he would get better. Before he got sick, Philip had decided he only wanted peace. His health did not improve, and he died the following year.

For the English, especially Queen Elizabeth, it seemed like luck had saved England. However, she was unhappy with Essex because his Azores trip failed and he left England's coast unprotected. The English got important information from the captured Spanish ships and prisoners. They quickly learned what was happening, including the goals and overall plan of the Spanish Armada.

Howard was rewarded by the Queen when he returned. He was given the title Earl of Nottingham.

Lessons were learned from this event. At Falmouth, a military engineer named Paul Ivey was in charge of making the castles at St Mawes and Pendennis stronger. This was done right away. Prisoners had said that another invasion would be tried the next summer, but only if Falmouth or Milford had been captured. An English spy in Spain confirmed this. He said the Spanish were confused but "bragged about what they would do next Spring." The defenses of Plymouth and Milford Haven were also improved. Local militia units were trained better.

The Spanish would never again try to send a large naval Armada directly at England. The cost had almost ruined Spain's finances again. It wasn't as bad as the previous year's failure, though, because gold and silver were still arriving from the Americas. Spain's huge debt grew, and soon after the campaign, new plans were made to pay it off.

The failure of the Armada meant England now had the upper hand at sea. England could still send expeditions to Spain without much trouble. For the first time in English naval history, they could effectively block enemy ships far from their own coasts. For example, William Monson and Richard Leveson led a notable expedition off Sesimbra in 1602. England could also defend the Channel. A few months later, a Spanish fleet of galleys was defeated by English and Dutch forces. It was only when peace was made that Spain's colonies and merchant ships were safe from England's "sea dogs."

The new King, Philip III, who took over in 1598, was more careful. With advice from the Duke of Lerma, he tried one more attack. This time, it was aimed at Ireland in 1601. The goal was to support Irish clans against English rule. This Armada succeeded in landing a much smaller force, even after a severe storm almost stopped the operation again. However, this venture also ended in disaster. The entire Spanish force surrendered after their defeat at the Battle of Kinsale.

Legacy

In 1953, during the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II, a local ship in Aberdyfi was made to look like the Spanish ship The Bear of Amsterdam. It was placed in the middle of the river and set on fire. A restaurant in the same town is also named after the ship.

See also

In Spanish: Invasión española de Inglaterra de 1597 para niños

In Spanish: Invasión española de Inglaterra de 1597 para niños

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |