Bunya pine facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Bunya pine |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Division: | Pinophyta |

| Class: | Pinopsida |

| Order: | Pinales |

| Family: | Araucariaceae |

| Genus: | Araucaria |

| Section: | A. sect. Bunya |

| Species: |

A. bidwillii

|

| Binomial name | |

| Araucaria bidwillii Hook., 1843

|

|

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The bunya pine (scientific name: Araucaria bidwillii) is a huge evergreen tree. It's part of the Araucariaceae plant family. People sometimes call it the "false monkey puzzle tree."

You can find it naturally in southeast Queensland, Australia. There are also two smaller groups of these trees in the World Heritage listed Wet Tropics of northeastern Queensland. Many old bunya pines have been planted in New South Wales and around Perth, Western Australia.

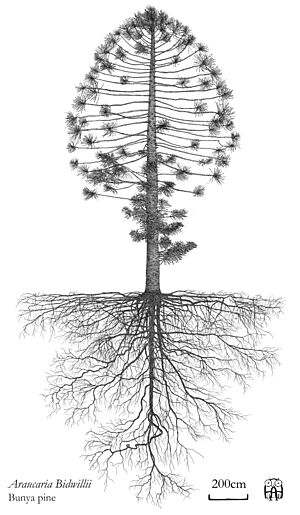

These amazing trees can grow very tall, up to 30 to 45 meters (about 98 to 148 feet). The tallest one known today is in Bunya Mountains National Park in Queensland. In 2003, it was measured at 169 feet (about 51.5 meters) tall!

The bunya pine is the only living species left from a group of trees called Section Bunya within the Araucaria genus. This group used to be very diverse and found all over the world during the time of the dinosaurs. Some ancient species had cones that looked like the bunya pine's cones. Scientists have found fossils of this group in South America and Europe. The tree's scientific name honors John Carne Bidwill, a botanist who discovered it in 1842.

Contents

What is a Bunya Pine?

The bunya pine has many names from different Australian Aboriginal languages, like bunya, bonye, bunyi, or bunya-bunya. Europeans later called it the Bunya Pine.

Even though it's called a "pine," the Araucaria bidwillii is not a true pine tree. It belongs to the same group as the famous monkey puzzle tree (Araucaria araucana). That's why it's sometimes known as the "false monkey puzzle tree."

Bunya trees can reach heights of 30 to 45 meters (98 to 148 feet). Their cones, which hold the tasty kernels, are as big as soccer balls!

The cones release their seeds, which are about 5 to 6 centimeters (2 to 2.5 inches) long. These seeds taste sweet before they are fully ripe. Once ripe, they taste like roasted chestnuts. Bunya trees usually produce a lot of cones every three years, around January.

In southeast Queensland, the trees pollinate in September or October. The cones then fall 17 to 18 months later, from late January to early March. Heavy rain or drought can change when pollination happens.

Where Do Bunya Pines Grow?

Bunya pines are native to Queensland, Australia. Historically, they were very common in many areas of South East Queensland and Wide Bay-Burnett. Today, the natural bunya forests in these regions have become smaller due to farming. You can still find them in places like the Blackall Range, Bunya Mountains, and along the upper Brisbane River and Mary River.

About 1500 kilometers (930 miles) to the north, you can find bunya pines again in the wet tropics of northeastern Queensland. Here, the natural groups of these trees are rare and limited to a few spots like Cannabullen Falls and Mount Lewis National Park.

The bunya pine's limited spread in Australia is partly because Australia became drier, leading to a loss of rainforests. Also, their large seeds don't spread very far. The remaining trees in the Bunya Mountains and Mount Lewis have good genetic diversity.

The cones are big, have soft shells, and are full of nutrients. They fall whole to the ground before breaking open. It's thought that large animals, perhaps even dinosaurs, might have helped spread the seeds long ago. This makes sense because the seeds are so big and full of energy.

When Europeans first arrived, bunya pines were very common in southern Queensland. In fact, a special Bunya reserve was created in 1842 to protect them. This reserve was later removed in 1860. Today, you usually see bunya pines in small groups or as single trees. However, they are still quite common on and near the Bunya Mountains.

How Bunya Pines Live and Grow

Bunya pines have an interesting way of germinating. Their seeds first grow an underground tuber (like a potato). The shoot that grows above ground appears later, sometimes over several years. This slow and spread-out germination might help the seedlings grow when conditions are best. It could also help them survive fires. This unpredictable germination makes it hard to grow bunya pines in tree farms.

The cones are large, measuring 20 to 35 centimeters (8 to 14 inches) across. They can weigh as much as 18 kilograms (40 pounds)! Large birds like cockatoos help open them. Or, the cones break apart when they are ripe to release the big seeds, which are 3 to 4 centimeters (1 to 1.5 inches) long.

While there are no known animals that specifically spread bunya seeds, some animals eat them. Bush rats and other types of rats are known to eat the seeds and tubers. Bush rats have even been seen hiding bunya seeds uphill from the parent trees, which might help new trees grow on ridges. Brushtail possums have also been seen carrying the seeds up trees. A study in 2006 showed that the short-eared possum (Trichosurus caninus) helps spread bunya seeds.

Many natural groups of bunya pines have become smaller because people cut them for timber, built dams, and cleared land for farms. Most bunya pine populations are now protected in national parks and reserves.

A new problem for bunya pine tree farms in Southeast Queensland is the introduction of Red deer. Unlike possums and rodents, red deer eat the bunya cones while they are still whole. This stops the seeds from being spread.

Cultural Importance of the Bunya Pine

The bunya tree produces edible kernels, which are the seeds inside the cones. When the cones are ripe, they fall to the ground. Each part of the cone holds a kernel in a tough shell. You can boil or roast these kernels, and the shell will split open. The kernels taste similar to chestnuts.

The cones were a very important food source for Indigenous Australians. Each Aboriginal family would own a group of bunya trees. These trees were passed down through generations. This is thought to be the only time Aboriginal people owned personal property that was inherited.

When the cones fell and the fruit was ripe, large harvest festivals would sometimes happen. These festivals took place every two to seven years. People from different groups would put aside their differences and gather in the Bunya Mountains to feast on the kernels. Local people, who were responsible for the trees, would send messages to invite people from hundreds of kilometers away to meet at specific places. These gatherings included Aboriginal ceremonies, settling arguments, arranging marriages, and trading goods.

This was probably Australia's largest Indigenous event. Many different tribes, sometimes thousands of people, traveled long distances to these gatherings. They came from places as far as Charleville, Bundaberg, Dubbo, and Grafton. They would stay for months to celebrate and feast on the bunya nuts. The bunya gatherings were like a truce, with lots of trading, discussions, and negotiations about marriages and local issues. Because bunya trees were sacred, some tribes would not camp among them. Also, in some regions, the tree was never to be cut down.

Representatives from many groups across southern Queensland and northern New South Wales would meet. They discussed important topics about the environment, social relationships, and their traditional stories (The Dreaming). Many conflicts were settled, and consequences for breaking laws were discussed.

Thomas Petrie (1831–1910) wrote about a Bunya festival he attended. When he was 14, he went with Aboriginal people from Brisbane to a festival at the Bunya Range (now the Blackall Range). His daughter, Constance Petrie, wrote down his stories. He said the trees produced fruit every three years, but this might not be exact. Ludwig Leichhardt also wrote about his trip to a Bunya feast in 1844.

Because Aboriginal people had such a strong connection to the trees, the government in 1842 made it illegal for settlers to take land or cut timber in a special Bunya district. This district was removed in 1860. Aboriginal people were eventually forced out of the forests, and they could no longer hold their festivals. The forests were cut down for timber and cleared for farming.

Bunya Pines Today

Indigenous groups like the Wakawaka, Githabul, Kabi Kabi, Jarowair, Goreng goreng, Butchulla, Quandamooka, Baruŋgam, Yiman, and Wulili still have cultural and spiritual ties to the Bunya Mountains today. They use their traditional ecological knowledge to help manage the national park and conservation areas. The Bunya Murri Ranger project is currently working in the mountains.

Uses of the Bunya Pine

Indigenous Australians eat the bunya nut both raw and cooked. They roast or boil them. They also eat them when they are not fully grown. Traditionally, the nuts were ground into a paste. This paste was eaten directly or cooked on hot coals to make bread. The nuts were also stored in the mud of running creeks. Eating them fermented was considered a special treat.

Besides eating the nuts, Indigenous Australians also ate bunya shoots. They used the tree's bark to start fires.

Bunya nuts are still sold as a regular food item in grocery stores and roadside stalls in rural southern Queensland. Some farmers in the Wide Bay and Sunshine Coast regions have tried growing bunya trees to sell their nuts and timber.

Bunya timber has always been highly valued for making musical instruments, especially the soundboards of stringed instruments. Since the mid-1990s, the Australian company Maton has used bunya wood for its acoustic guitars. Another Australian company, Cole Clark, also uses bunya for most of its acoustic guitar soundboards. Cabinet makers and woodworkers also value the timber, and it has been used for furniture for over a century.

However, its most popular use today is as a 'bushfood' by people interested in native Australian foods. Many new recipes have been created for the bunya nut. You can find it in pancakes, biscuits, breads, casseroles, or even as "bunya nut pesto" or hummus. The nut is very nutritious and has a unique flavor, like a starchy potato and chestnut.

When you boil bunya nuts in water, the water turns red. This makes a tasty tea.

Bunya nuts are very healthy. They are about 40% water, 40% complex carbohydrates, 9% protein, and 2% fat. They also contain potassium and magnesium. Bunya nuts are gluten-free, so bunya nut flour can be used by people who can't eat gluten.

Growing Bunya Pines

Bunya nuts take a long time to sprout. In one test, 12 seeds planted in Melbourne took about six months to germinate. The first roots appeared after one year. The first leaves form a small cluster and are dark brown. They only turn green when the first stem branch grows. Young leaves are soft, but as they get older, they become very hard and sharp. You can also grow bunya pines from cuttings, but only if the cuttings come from upright-growing shoots. Cuttings from side shoots won't grow straight.

In Australia's changing climate, the bunya's spread-out germination helps make sure at least some seedlings survive to replace the parent tree. A study by Smith in 1999 looked at bunya seed germination. He planted 100 seeds from two cones collected from a tree in Petrie, Queensland. The seeds were planted in February 1999 and watered weekly. Out of 100 seeds, 87 sprouted. 55 of them sprouted between April and December 1999. Another 32 sprouted between January and September 2000. One sprouted in January 2001, and the last one appeared in February 2001.

Once they are established, bunya pines are quite tough. They can grow as far south as Hobart in Australia (42° S) and Christchurch in New Zealand (43° S). They can also grow as far north as Sacramento in California (38° N) and Coimbra in Portugal. They even grow in the Dublin area of Ireland (53ºN) in special protected spots. Bunya pines can reach 35 to 40 meters (115 to 130 feet) tall and live for about 500 years.

Tree Structure

The bunya pine, like many trees in the Araucariaceae or Abies families, changes its growth pattern as it gets older. When it's young, it grows in a very organized, layered way (called Massart's model). As it gets older, it gradually changes to a different, more branched structure (called Rauh's model).

Bunya Pine in Pop Culture

A bunya pine tree in East Los Angeles, California is famous from the 1993 film Blood In Blood Out. In the movie, the tree, known as "El Pino" (Spanish for "the pine"), is an important symbol for the main characters. Because of this movie, the tree has become well-known and is visited by fans from all over the world. In late 2020, a prank claiming the tree would be cut down caused a brief panic in the local area.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Araucaria australiana para niños

In Spanish: Araucaria australiana para niños

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |