Camisards facts for kids

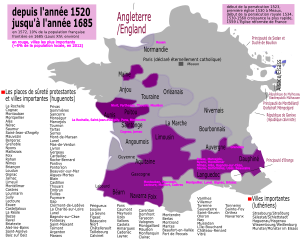

The Camisards were Huguenots, who were French Protestants. They lived in the tough and isolated Cévennes region and nearby Vaunage in southern France. In the early 1700s, they started a fight against unfair treatment. This happened after Louis XIV made Protestantism illegal by canceling the Edict of Nantes.

The Camisards fought across the mostly Protestant Cévennes and Vaunage areas. This included parts of the Camargue near Aigues Mortes. Their revolt began in 1702. The worst fighting lasted until 1704, with smaller clashes continuing until 1710. A final peace was made by 1715. However, full religious freedom, called the Edict of Tolerance, wasn't officially signed until 1787.

Contents

What's in a Name?

The name camisard comes from the Occitan language. It might come from a simple linen shirt or smock called a camisa. This was the kind of shirt peasants wore instead of a uniform. Another idea is that it comes from Occitan: camus, meaning "paths." The word Camisada, which means "night attack," also comes from their fighting style.

A Time of Trouble: The Story of the Camisards

In April 1598, King Henry IV signed the Edict of Nantes. This ended the religious wars that had torn France apart. Protestants were given some rights and the freedom to worship as they believed. This "fundamental and irrevocable law" was kept by Henry's son, Louis XIII.

The King's Rules and the Dragonnades

But in October 1685, Henry's grandson, King Louis XIV, canceled the Edict of Nantes. He issued his own Edict of Fontainebleau. King Louis wanted everyone in France to follow only one religion: Catholicism. As early as 1681, he started using "dragonnades." These were forced conversions carried out by soldiers called dragoons. These soldiers were called "missionaries in boots." They would stay in Protestant homes to make people convert to the official church or leave the country. The Cévennes region strongly resisted this.

The Edict of Fontainebleau took away all rights and protections from the Huguenots. For about twenty years, they faced harsh treatment. Protestant worship and private Bible readings were banned. Within weeks, over 2,000 Protestant churches were burned. This was done under the direction of Nicholas Lamoignon de Basville, a royal official. Whole villages were destroyed and burned. Pastors and worshippers were captured, then sent away, forced to work on ships, or killed.

Seventy-five priests, led by Abbot François Langlade, were sent to the Cévennes. Soldiers with crosses on their guns forced peasants to sign papers saying they would convert. They also forced them to attend Catholic mass. But the peasants kept holding secret meetings. Huguenots who had special skills fled to other countries. The King responded by closing the borders.

Prophets and Resistance

Protestant peasants in Vaunage and Cévennes resisted. They were led by teachers known as "prophets," like François Vivent and Claude Brousson. Vivent told his followers to arm themselves in case royal soldiers attacked them. Several important prophets were executed, including François Vivent in 1692 and Claude Brousson in 1698. Many more were sent away. This left the groups without leaders, so less educated but more spiritual preachers took over. One such leader was Abraham Mazel, a wool-comber.

The Catholic church was compared to the Beast of the Apocalypse. The secret prophets claimed to have seen this in their dreams. Mazel, for example, dreamed of black oxen in his garden. A voice told him to chase them away. From 1700, these secret prophets and their armed followers hid in houses and caves in the mountains.

The Fight Begins

Open fighting started on July 24, 1702. This was when François Langlade, the Abbé of Chaila, was killed at le Pont-de-Montvert. He was a local symbol of the King's harsh rule. Langlade had recently arrested seven Protestants who tried to escape France. A group of Camisards, led by Abraham Mazel, peacefully asked for the prisoners to be freed. When this was refused, they began the killing. The Catholic State quickly praised the abbé as a martyr.

The Camisards worked on their own. During the day, most went back to their village lives. They were mostly farmers or craftspeople. They had no noble leaders. They knew all the paths and sheep trails very well. They called themselves the Children of God. Their actions were driven by religion, not by money or politics.

Brave Leaders and Tough Times

Young Jean Cavalier and Pierre Laporte (Rolland) led the Camisards. They fought the royal army using irregular warfare methods. They held their own against much larger forces in several big battles.

The violence grew as both sides committed terrible acts. Camisards attacked Catholic villages like Fraissinet-de-Fourques, Valsauve, and Potelières. Basville, a government official, forced everyone from Mialet and Saumane to leave their homes. Then, in the autumn of 1703, with the King's approval, a plan called the "Burning of the Cévennes" began. This destroyed 466 small villages and forced their people to leave.

Other Protestants, like those in Fraissinet-de-Lozère, stayed loyal to the King. They fought the Camisards. Yet, they still lost their homes during the "Burning of the Cévennes."

"White Camisards," also known as "Cadets of the Cross," were Catholics from nearby towns. They wore a small white cross on their coats. When they saw their old enemies on the run, they formed groups to loot and hunt down the rebels.

Other opponents of the Protestants included 600 miquelet sharpshooters from Roussillon. The King hired them as paid soldiers.

The End of the Fighting

In 1704, Claude Louis Hector de Villars, the royal commander, offered some deals to the Protestants. He even promised Cavalier a command in the royal army. Cavalier accepted this offer, which helped end the revolt. However, others, like Laporte, refused to give up unless the Edict of Nantes was brought back.

Some scattered fighting continued until 1710. But the real end of the uprising came when the Protestant minister Antoine Court arrived in the Cévennes. He helped rebuild a small Protestant community. This community was mostly left in peace, especially after King Louis XIV died in 1715.

Who Were the Camisards?

About 42% of the Camisards were peasants from the Cévennes. The other 58% were rural craftspeople. Most of these craftspeople (75%) worked with wool, like wool-combers or weavers. All of them spoke Occitan. No noblemen were involved, and none had military training. There wasn't one single army or leader. Instead, each area had its own organizers and occasional soldiers.

Key Leaders

Some important leaders were:

- Gédéon Laporte

- Salomon Couderc, with Abraham Mazel in Le Bougès and Mont Lozère.

- Henri Castanet (1674–1705) in charge of Mont Aigoual.

- Pierre Laporte (Rolland) (1680–1704) in the Basses-Cévennes, Mialet, and Lassalle.

- Jean Cavalier (1681–1704) in the plains of Bas-Languedoc, between Uzès and Sauve.

Inspiring Prophets

Since official Protestant pastors were rounded up, a group of prophets led secret religious meetings. Notable among them were:

- Esprit Séguier

- Abraham Mazel

- Elie Marion

- Jean Cavalier

The visions of these prophets inspired the war's actions. They made the peasants feel unbeatable. The peasants marched into battle singing Psalms, which made their enemies nervous.

Timeline of the Camisard Revolt

1701

- June: The Vallérargues event, where people took back captured prophets from priests.

1702

- July 24: François Langlade, the Abbé du Chayla, two priests, and a Catholic family were killed at Dévèze.

- August 12: Esprit Séguier is executed. This is often seen as the start of the war.

- September 11: Battle at Champdomergue, a hill near (Le Collet-de-Dèze). No clear winner.

- October 22: Battle at Témélac. Gédéon Laporte is killed.

- December 24: Jean Cavalier, with 70 Camisards, captured the town of Alès, which had 700 soldiers.

- December 28: The Camisards captured Sauve.

1703

- January 12: Jean Cavalier took Val de Barre (Nîmes) from the royalist Count de Broglie.

- February: Count de Broglie was replaced by Field-Marshal de Montrevel. More troops were sent.

- February 26: Camisards under Castanet attacked the people of Fraissinet-de-Fourques.

- March 6: Battle of Pompignan – the Camisards lost.

- April 1: The royalist Moulin de l'Agau attack.

- April: People from Mialet and Saumane were forced to move to Perpignan in Roussillon.

- April 29: Jean Cavalier was defeated at Tour de Billot (Alès).

- May 18: Battle of Bruyès.

- September 12: Catholics were attacked at Potelières.

- September 20: Catholics were attacked at Saturargues (Lunel) and Saint-Sériès.

- Autumn: The "Burning of the Cévennes" policy began. Villagers were forced to leave 466 villages, which were then burned.

- Autumn: The Catholic Cadets of the Cross (White Camisards) appeared. They looted and attacked.

- December 20: Battle of the Madeleines (Tornac).

1704

- March 15: The battle of Devès de Martignargues (Vézénobres). Jean Cavalier defeated a Catholic regiment.

- March: Field-marshal de Montrevel was replaced by Field-marshal de Villars.

- April 16: de Montrevel defeated Cavalier at the Battle of Nages (while waiting for de Villars).

- April 19: Cavalier's hidden supplies were found in caves at Euzet.

- April 20: de Villars took command and suggested talking to the Camisards.

- May: Talks began. Cavalier agreed to surrender without conditions and accepted a command in the royal army.

- August 13: Pierre Laporte (Rolland) died at Castelnau-les-Valence.

- October: Other leaders left France.

Their Lasting Impact

Jean Cavalier later joined the British and became governor of the island of Jersey.

Beyond the Battlefield

A group of former Camisards, who believed the end of the world was near, moved to London in 1706. They were led by Elie Marion and were said to have links with the Alumbrados. People often made fun of them, and they faced some official punishment as the "French Prophets." However, their ideas and writings later influenced thinkers like Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Ann Lee, who started the Shaker movement.

Keeping Protestantism Alive

After the main Camisard groups were stopped, the French government didn't want to start another revolt. So, they became less harsh towards Protestants. Many former Camisards went back to a more peaceful way of life. From 1715 onwards, they helped rebuild Protestantism, which was still illegal but much better organized. This was thanks to the leadership of Antoine Court and many traveling pastors who were allowed back into the country.

A Story That Lives On

In his book La légende des Camisards, history professor Philippe Joutard wrote about the strong oral stories about the Camisards that still exist in the Cévennes region today. He also noticed how this amazing period of history has a "powerful attraction." Many separate events have been woven into these stories over time.

Since these stories are mostly passed down through families, they often highlight ancestors who stayed true to their beliefs. This is sometimes more than focusing on the heroic leaders of the revolt. Because of this, the story goes beyond just religion. It becomes about a general attitude of resistance and not conforming. This has shaped a whole way of thinking, politics, and culture in the region. Philippe Joutard also noted that even the few Catholics in this Protestant area tend to tell their history in a similar way to their former religious rivals. The Camisards' impact on the Cévennes is very deep and lasting.

See Also

- Marie Durand

- Pierre Durand, Huguenot

- Paul Rabaut

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |