Nicolas Fatio de Duillier facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Nicolas Fatio de Duillier

|

|

|---|---|

Portrait by an unknown artist, in the collection of the Bibliothèque de Genève

|

|

| Born | 26 February 1664 Basel, Swiss Confederacy

|

| Died | 10 May 1753 (aged 89) Madresfield, Great Britain

|

| Nationality | Republic of Geneva |

| Alma mater | University of Geneva |

| Known for | Zodiacal light, Le Sage's theory of gravitation, jewel bearing |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Mathematics, astronomy, physics, watchmaking |

| Academic advisors | Jean-Robert Chouet |

| Influences | Giovanni Domenico Cassini, Christiaan Huygens, Isaac Newton |

| Influenced | Gabriel Cramer, Georges-Louis Le Sage |

Nicolas Fatio de Duillier (born 16 February 1664 – died 10 May 1753) was a brilliant mathematician, scientist, astronomer, and inventor. He was born in Basel, Switzerland. Nicolas grew up mostly in the independent Republic of Geneva. Later, he spent much of his adult life in England and Holland.

Fatio is famous for several important things. He worked with Giovanni Domenico Cassini to correctly explain zodiacal light, a glow seen in the night sky. He also invented a special idea about how gravity works, called the "push" or "shadow" theory. He was very close friends with famous scientists like Christiaan Huygens and Isaac Newton. Fatio also played a part in the big debate about who invented calculus first.

Beyond his scientific ideas, he invented a new way to make tiny, strong parts called jewel bearings for mechanical watches and clocks. These parts made watches much more accurate and long-lasting.

Nicolas Fatio was chosen to be a Fellow of the Royal Society of London when he was only 24. This was a great honor! However, he never became as famous as his early work suggested. In his later life, he became very involved with a religious group. This affected his scientific reputation. Still, Fatio kept working on technology, science, and his religious studies until he passed away at 89.

Contents

Early Life and Learning

Family and Education

Nicolas Fatio was born in Basel, Switzerland, in 1664. His family originally came from Italy. They moved to Switzerland after the Protestant Reformation. Nicolas was one of nine children. His father, Jean-Baptiste, wanted him to become a pastor. His mother, Cathérine, hoped he would work for a German prince. But Nicolas chose a path in science instead.

His older brother, Jean Christophe Fatio, was also a scientist. He became a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1706. Jean Christophe wrote about a solar eclipse he saw in Geneva. Nicolas Fatio himself never married.

Nicolas went to school at the Collège de Genève. Then, he studied at the Académie de Genève (now the University of Geneva). There, he was taught by Jean-Robert Chouet, a follower of the philosopher René Descartes. Before he was 18, Fatio wrote to Giovanni Domenico Cassini, a famous astronomer in Paris. He suggested new ways to measure distances in space. He also offered an idea about the shape of Saturn's rings.

Discoveries in Astronomy

With support from his teacher, Fatio traveled to Paris in 1682. Cassini welcomed him warmly. That same year, Cassini shared his findings about zodiacal light. Fatio observed this light again in Geneva in 1684. In 1685, he improved Cassini's theory.

Fatio's own letter about the "extraordinary light" was published in 1686. In it, he correctly explained that zodiacal light is sunlight. This light is scattered by a cloud of tiny dust particles in space. This "zodiacal cloud" sits along the ecliptic plane, which is the path the Earth takes around the Sun.

Fatio also studied how the eye's pupil changes size. He described parts of the eye in a letter in 1684. That same year, he wrote an article about how to make better lenses for telescopes.

In 1684, Fatio learned about a plot to kidnap Prince William of Orange. Fatio warned the Prince. He then traveled to Holland in 1686 to make sure the Prince was safe.

Life in Holland and England

In Holland, Fatio met Christiaan Huygens, another very important scientist. They started working together on mathematical problems, especially about the new calculus. Huygens was very impressed with Fatio's math skills.

Fatio arrived in England in June 1687. He believed the two greatest scientists alive were Robert Boyle and Christiaan Huygens. In London, Fatio met many important people. He worked on new ways to solve math problems. He also learned about Isaac Newton's upcoming book, Principia.

Joining the Royal Society

At just 24 years old, Fatio was elected a fellow of the Royal Society in 1688. This is a very respected group of scientists. That year, Fatio explained Huygens's idea of how gravity might work. He tried to connect it to Newton's ideas about universal gravity.

Fatio met Newton, probably for the first time, in June 1689. They quickly became friends. Newton even suggested they share rooms in London. In 1690, Fatio wrote to Huygens about his own idea for how gravity works. This idea later became known as "Le Sage's theory of gravitation".

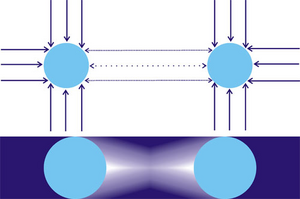

Fatio's theory suggested that tiny particles stream through space. These particles push on objects, causing them to be attracted to each other. He thought this idea was similar to how he explained zodiacal light. Fatio kept working on this theory for the rest of his life.

Fatio turned down Newton's offer to be his assistant in Cambridge. Instead, he went to Holland in 1690 to tutor some nephews of a friend. There, he shared a list of corrections for Newton's Principia with Huygens. Fatio and Huygens worked together on problems about math, gravity, and light. Fatio returned to London in 1691.

Fatio encouraged Newton to write a new book on integration. He also hoped to work with Newton on a new edition of Principia. This new edition would include Fatio's ideas about gravity. By late 1691, Fatio realized Newton wouldn't do this. But he still hoped to help Newton with corrections. He even wrote that he understood much of the book better than anyone else.

Newton and Fatio also wrote many letters about alchemy between 1689 and 1694. Fatio helped Newton connect with another alchemist. By 1694, Fatio was tutoring a young nobleman, Wriothesley Russell. He traveled with his student to Oxford and Holland.

The Calculus Debate

Fatio read Newton's work on calculus. He became convinced that Newton had understood calculus completely for a long time. This made Fatio feel his own math discoveries were not as new. In 1696, Johann Bernoulli, a friend of Gottfried Leibniz, challenged mathematicians with a difficult problem. Many scientists solved it, including Newton.

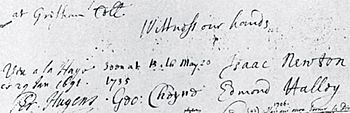

In 1699, Fatio published a pamphlet with his solutions to this problem and another one. In his book, Fatio pointed out his own early work on calculus. But he strongly emphasized that Newton was the first to invent it. He also questioned the claims of Leibniz and his followers.

Fatio wrote: "I recognize that Newton was the first and by many years the most senior inventor of this calculus." He suggested that if Leibniz, the second inventor, copied anything from Newton, others should decide. This made Johann Bernoulli and Leibniz very angry. Leibniz said that Newton himself had admitted Leibniz's independent discovery in his Principia.

Fatio's response to his critics was published in 1701. His writings about the history of calculus are seen as an early part of the big argument between Newton and Leibniz. This argument, called the priority dispute, was about who invented calculus first.

Watchmaking Inventions

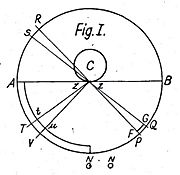

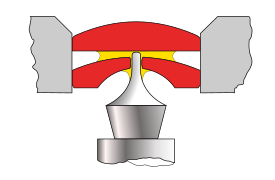

In the 1690s, Fatio made an important invention for watches. He found a way to drill a small, perfectly round hole in a ruby using a diamond drill. These pierced rubies could be used as jewel bearings in mechanical watches. They reduce friction and wear inside the watch. This made watches more accurate and last longer.

Fatio tried to get watchmakers in Paris interested, but they weren't. Back in London, he teamed up with two brothers, Peter and Jacob Debaufre, who had a successful watchmaking shop. In 1704, Fatio and the Debaufres got a patent for Fatio's invention. This meant they had the sole right to use it in England for 14 years.

In 1705, Fatio showed watches with these jewels to the Royal Society. Even Isaac Newton was interested. Fatio's method for piercing rubies remained a special skill of English watchmakers for many years. Today, jewel bearings are still used in high-quality mechanical watches.

Later Life and Legacy

Fatio visited Switzerland several times in the early 1700s. He worked with his brother to map the mountains around Lac Léman. He also studied religious texts. Back in London, Fatio worked as a math tutor. In 1706, he became involved with a group called the "French prophets." This group had strong religious beliefs.

Fatio traveled as a missionary with the French prophets. He went as far as Smyrna (modern-day Izmir, Turkey). He returned to Holland in 1713 and then settled in England. His strong religious views sometimes caused problems for his scientific reputation.

In 1717, Fatio presented papers to the Royal Society about the precession of the equinoxes and climate change. He looked at these topics from both a scientific and religious viewpoint. He then moved to Worcester, where he continued his scientific studies and other interests.

After Isaac Newton died in 1727, Fatio wrote a poem about Newton's genius. In 1732, Fatio helped design Newton's monument in Westminster Abbey. He also helped write the words for it.

Fatio passed away in 1753 in Madresfield. Many of his scientific papers were later bought by Georges-Louis Le Sage. These papers are now kept in the Geneva Library.

Fatio's Inventions

Nicolas Fatio invented many things throughout his life. The most important was the jewel bearing for watches. But his inventions went beyond watchmaking.

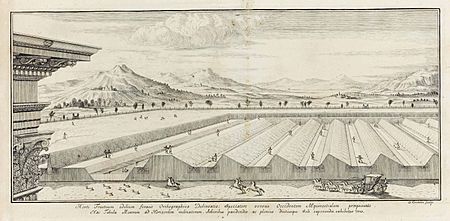

To help plants grow better, Fatio suggested building sloping fruit walls. These walls were angled to collect as much heat from sunlight as possible. He published a book about this invention in 1699. Fatio also thought of a way for a mechanism to turn and follow the Sun. These ideas were later replaced by modern greenhouses.

He also worked on improving how lenses for telescopes were made. He even had ideas for using a ship's movement to grind corn or raise anchors. He designed a special observatory for ships. He also measured the height of mountains around Geneva.

The Push-Shadow Gravity Theory

Fatio believed his greatest work was his explanation of Newtonian gravity. He thought gravity was caused by tiny, fast-moving particles hitting objects. He was inspired by Christiaan Huygens's earlier ideas about gravity. He also thought it was similar to how he explained zodiacal light.

Fatio's theory suggested that these tiny particles would also slow down objects moving through space. He tried to explain how this "drag" could be very small. However, scientists like Huygens were not convinced. Newton also stopped trying to explain gravity with these kinds of interactions.

Fatio never published his full work on this theory during his lifetime. But he kept working on it. A copy of his writings was later seen by Gabriel Cramer, a mathematician. Cramer published a summary of Fatio's theory in 1731 without saying who came up with it. Another scientist, Georges-Louis Le Sage, later came up with the same idea independently. Because of this, the theory is now often called "Le Sage's theory of gravitation".

Even though modern science does not accept this theory for gravity, the idea of particles causing attraction is interesting. Some scientists in the 19th century, like James Clerk Maxwell, found it worth studying. Fatio's full explanation of his gravity theory was finally published in 1929 and 1949, long after his death.

Writings

Books by Fatio

Fatio wrote several books during his life:

- Epistola de mari æneo Salomonis (1688) – A letter about Solomon's Brazen Sea.

- Lineæ brevissimæ descensus investigatio geometrica duplex (1699) – About the line of briefest descent and minimum resistance.

- Fruit-walls improved by inclining them to the horizon (1699) – About his invention of sloping fruit walls.

- N. Facii Duillerii Neutonus. Ecloga. (1728) – A poem about Newton.

- Navigation improved (1728) – About finding latitude at sea.

He also helped publish a religious prophecy in 1714.

Articles in Journals

Fatio published articles in different scientific journals:

- Lettre sur la manière de faire des Bassins pour travailler les verres objectifs des Telescopes (1684) – About making lenses for telescopes.

- Lettre à M. Cassini touchant une lumière extraordinaire qui paroît dans le Ciel depuis quelques années (1686) – About zodiacal light.

- Réflexions sur une méthode de trouver les tangentes de certaines lignes courbes (1687) – About finding tangents of curves.

- "Epistola ad fratrem Joh. Christoph. Facium" (1713) – A letter to his brother about his solution to a math problem.

- "Four theorems, with their demonstration, for determining accurately the sun's parallax" (1745) – About measuring the Sun's distance.

He also wrote articles on astronomy and ancient measurements for the Gentleman's Magazine in 1737–38.

Unpublished Works

When Fatio died, he left many unpublished writings. Some of these are now in the Geneva Library. A few of his papers and letters are in the British Library. These include a Latin poem about the plot against Prince William of Orange. They also describe his jeweled watches.

Some of Fatio's letters were published later in the collected works of Christiaan Huygens and Isaac Newton. His important work on the push-shadow theory of gravity was only published long after his death.

Images for kids

| Chris Smalls |

| Fred Hampton |

| Ralph Abernathy |