Charles Townshend (British Army officer) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

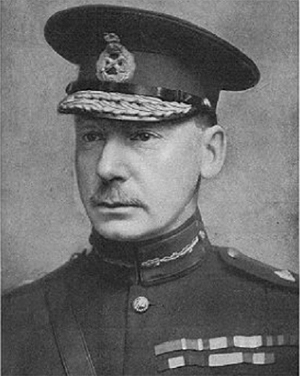

Sir Charles Vere Ferrers Townshend

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 21 February 1861 London, United Kingdom |

| Died | 18 May 1924 (aged 63) Paris, France |

| Allegiance | United Kingdom |

| Service/ |

Royal Marines (1881–1886) British Army (1886–1920) |

| Years of service | 1881–1920 |

| Rank | Major general |

| Commands held | 6th (Poona) Division 4th Rawalpindi Brigade 9th Jhansi Brigade 54th East Anglian Division 44th Home Counties Division Orange River Colony District 12th Sudanese Battalion |

| Battles/wars | Mahdist War Hunza–Nagar Campaign Chitral Expedition North-West Frontier First World War |

| Awards | Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath Distinguished Service Order |

| Relations | George Townshend, 1st Marquess Townshend |

| Member of Parliament for The Wrekin |

|

| In office 20 November 1920 – 26 October 1922 |

|

| Preceded by | Charles Palmer |

| Succeeded by | Howard Button |

| Personal details | |

| Political party | Independent Parliamentary Group |

Sir Charles Vere Ferrers Townshend (born February 21, 1861 – died May 18, 1924) was a British soldier. He became a Major General. During World War I, he led a military campaign in Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq).

His troops faced a long siege and were captured at the Siege of Kut in 1916. This was a major defeat for the Allies. Unlike his soldiers, Townshend was treated well as a prisoner. He stayed on an island called Prinkipo until 1918. After the war, he was a Member of Parliament for a short time.

Contents

Early Life and Ambitions

Charles Townshend was born in London in 1861. He came from a well-known family. His great-great-grandfather was a famous military leader.

Charles was very ambitious. He hoped to inherit his family's important title and estate. He studied at Cranleigh School and a military college. In 1881, he joined the Royal Marine Light Infantry.

In 1884, Townshend joined a mission to rescue General Charles George Gordon in Khartoum. Gordon was a national hero. Townshend was impressed by how Gordon defied orders. He also saw how the public supported heroic generals.

Townshend loved French culture and spoke French fluently. He even preferred to be called "Alphonse." This sometimes annoyed his fellow officers. He was very ambitious and often asked for help to get promoted.

An Imperial Soldier's Adventures

Townshend served in the Sudan in 1884. He then joined the Indian Staff Corps in 1885. He also took part in the Hunza-Naga Campaign in 1891.

In 1894, he entertained George Curzon with French songs. In 1895, he was sent to Chitral, a remote area in northern India.

Hero of Chitral

Townshend became famous in Britain during the Siege of Chitral Fort in 1895. He was the commander of the besieged fort. His actions were widely reported in the British press.

From March to April 1895, his Indian force was surrounded by local tribesmen. Townshend ordered a retreat into the fort after a battle. He wrote about the intense fighting and lack of food.

After 46 days, Captain Fenton Aylmer's forces rescued the fort. Townshend returned to Britain as a national hero. He had dinner with Queen Victoria and received a special award.

His fame helped him become friends with important people. He also studied military history seriously. He learned from famous military thinkers like Ferdinand Foch and Carl von Clausewitz.

Many officers found Townshend difficult. But his soldiers, both British and Indian, liked him. He was known for being charismatic.

Fighting in Sudan

Townshend joined the British Egyptian army. He commanded the 12th Sudanese Battalion. He fought in the Sudan at the Battle of Atbara and Battle of Omdurman in 1898. For his bravery, he received the Distinguished Service Order.

General Herbert Kitchener personally asked Townshend to join his command. Townshend was promoted to major for his bravery. He was mentioned in official reports five times.

He spent his time fighting, learning Arabic, and training his soldiers. He also romanced a French aristocrat, Alice Cahen d'Anvers. He married her in 1898.

After Omdurman, Townshend left the Egyptian Army. He tried to get a command in South Africa. He eventually got a staff job in India.

Later Career Before WWI

Townshend continued to seek promotions. He was promoted to colonel in 1904. He became a military diplomat in Paris in 1905.

In South Africa, he commanded the Orange River Colony District. His wife brought French style to the area. Townshend's job was to help unite the colonies into the Union of South Africa.

He was promoted to brigadier general in 1909 and major-general in 1911. He commanded several divisions in Britain and brigades in India.

In 1911, he met General Foch in Paris. Foch warned him about Germany's plans to dominate Europe. Townshend's constant lobbying for promotions sometimes hurt his career.

World War I: The Mesopotamian Campaign

When World War I began, Germany tried to cause trouble in India. The Ottoman Empire also joined the war. The Ottoman leader called for a holy war against Britain and its allies.

Britain worried about Indian soldiers rebelling. Townshend was kept in India because he knew the area well. He wanted to fight on the Western Front in France, but his request was denied.

In April 1915, Townshend was given command of the 6th (Poona) Division in Mesopotamia. His job was to protect British oil fields from Ottoman attacks. He arrived in Basra in April.

Pushing Towards Baghdad

General John Nixon ordered Townshend to advance up the Tigris River. Their goal was to capture Amarah. Townshend and Nixon did not get along well.

Britain had already secured its oil fields. There was no real need to advance to Baghdad. But both Nixon and Townshend wanted to for prestige.

Townshend's force lacked heavy guns and supplies. They needed clean water, medical supplies, and more. Townshend knew about these problems but didn't discuss them with Nixon.

Townshend planned a clever advance using local boats. He called it the "Regatta up the Tigris." His men would move secretly across marshes at night.

Capturing Amarah

The advance started well on May 31, 1915. Townshend's artillery fired on Ottoman trenches. His men in boats outflanked the enemy. He called it "Regatta Week."

He had a low opinion of the local Marsh Arabs. He saw them as looters. Amarah was captured on June 3, 1915, mostly by tricking the enemy. Two thousand Ottoman soldiers were captured.

Townshend issued a press release that ignored his Indian soldiers. He claimed only 25 British soldiers had taken Amarah. He was popular with his men, despite his quirks.

Townshend was an aggressive commander. He was eager to take Baghdad. He wrote to his wife about his rapid pursuit of the enemy. He was a skilled tactician and willing to take risks.

After Amarah, Townshend fell ill from dirty water. He went to a hospital in Bombay. Ordinary soldiers did not have such good care.

Townshend returned to his command later that summer. He told London he could take Baghdad if he defeated the Ottomans at Kurna. Nixon wanted to ride into Baghdad in triumph.

By August 1915, the Gallipoli Campaign was a stalemate. The Ottomans sent more Turkish soldiers to stop Townshend. These Turkish units were much tougher than the Arab units he had faced.

Townshend learned that General Nureddin Pasha had dug in with 8,000 Turkish soldiers. Townshend's plan was to attack the strongest point with a small force. His main force would attack from the rear.

At Kut, his main force got lost in the desert at night. His diversionary force faced the full Ottoman counter-attack. Townshend later wrote that this nearly cost them the battle.

Luckily, his main force found the Ottoman camp and attacked from behind. This caused the Ottoman forces to collapse. Townshend's forces suffered heavy losses. He lost 1,229 men killed or wounded.

After his victory, Townshend issued a proud press release. He called the Battle of Kut-al-Amara one of the most important in British Indian history. The town of Kut-al-Amara was captured on September 28, 1915.

The campaign received much media attention in Britain. It gave the government good news during a difficult war. Townshend became a sensation.

Townshend was impressed that German field marshal Baron Colmar von der Goltz was sent to stop him. Goltz was a respected military historian. Townshend wanted to be promoted to lieutenant general. He believed taking Baghdad would help him achieve this.

He admired Napoleon and wanted to be a great commander. He even thought he could become commander-in-chief of the British Army.

Townshend suggested stopping at Kut-al-Amara to gather more strength. But General Nixon insisted on advancing to Baghdad. Townshend's troops were tired and lacked supplies.

Townshend always asked Nixon for more divisions. But he didn't ask for better logistics. His supply line was very long and slow. Illness also affected many Anglo-Indian soldiers.

Indian Muslim soldiers were unhappy fighting other Muslims. Townshend sent about 1,000 of them back to Basra. He believed they would desert rather than fight.

Townshend wrote to a friend in London. He warned that his troops were not good enough to take Baghdad. He feared a retreat would cause Arabs, Persians, and Afghans to rise up. He believed the main war was in Europe.

However, Townshend also wrote to his wife, Alice. He said he had a gift for making men love and follow him. He believed his division would "storm the gates of hell" for him.

Nixon ordered Townshend to continue to Baghdad without more troops. The Tigris River was too shallow for naval support. Townshend had advised against it, but his ambition pushed him forward.

He underestimated the Ottoman forces. He thought he faced less than 10,000 men. In reality, there were over 20,000. The British government desperately wanted a victory. They believed Townshend's reports.

On November 1, 1915, Townshend led his division from Kut-al-Amara. They reached Ctesiphon on November 20. Here, they met a large Ottoman force.

General Nureddin Pasha had four divisions. They were dug in at Ctesiphon. Townshend was fascinated by the ancient Arch of Ctesiphon. He saw it as a historical landmark.

Townshend divided his division into four columns. His plan was to attack the Ottoman flanks and rear.

The Battle of Ctesiphon

The Battle of Ctesiphon was fought hard for two days, starting November 22, 1915. Both Townshend and Nixon were involved in the fighting.

The battle began with an attack in the morning mist. Townshend believed the battle was won after capturing a key point. But he was shocked to find the Ottoman army was much larger.

During the battle, Townshend even demanded a change of uniform. His servant had to run across the battlefield to bring it. Ottoman cavalry intercepted Townshend's rear attack.

Townshend's forces were outnumbered. He was forced to pull back. He claimed Indian troops retreated without orders. After two days, Nureddin Pasha ordered his men to withdraw.

Both sides suffered heavy losses. Townshend had defeated Nureddin, but his division was too damaged to advance. He had lost one-third of his men.

Townshend decided to retreat back to Kut-al-Amara. He hoped to find shelter and wait for reinforcements. Nureddin Pasha pursued him closely.

On December 1, 1915, Nureddin caught up with Townshend. A sharp fight occurred, and the Ottomans were driven off. This gave Townshend a few days' lead.

Townshend arrived back in Kut on December 3, 1915. On December 7, the Ottoman forces surrounded Kut. The 6th Division was trapped.

The Siege of Kut-al-Amara

The Siege of Kut lasted five months. Townshend's men were surrounded and faced constant fire. They had dwindling supplies and suffered greatly.

Townshend was deeply affected when he realized he wouldn't take Baghdad. He could have retreated to Basra. But he chose to make a stand at Kut. He hoped to repeat his earlier success at Chitral. He knew a siege would force the British Army to send a relief force.

Townshend claimed his men were too tired to march further. He was influenced by how the press had praised General Gordon during a siege. Townshend wanted to be a "live Gordon," rescued and celebrated.

On December 10, 1915, Nureddin Pasha ordered an attack on Kut. Townshend repelled the attack with heavy losses for the Ottomans. On Christmas Day, the Ottomans attacked again.

Later, German Field Marshal Colmar Freiherr von der Goltz arrived. He stopped further storming attempts. He preferred to starve Townshend's men into surrender. Germany supplied powerful artillery guns.

Townshend complained about the Ottoman artillery fire. His men dug in beneath the ruins of Kut. They lived mostly underground. Soldiers suffered from lice, fleas, and mosquitoes.

Townshend's reports about supply shortages were exaggerated. His supplies lasted much longer than he claimed. These reports made him seem like a hero. They also pushed the British government to send a relief force.

Sir Fenton Aylmer led the relief force. But the Ottomans had strong defenses. British supply lines were stretched. All attempts to break the siege failed. Heavy rains made conditions worse.

The port of Basra was poorly managed. This made it hard to get supplies to the relief forces. Sir George Buchanan described the chaos at Basra. This mismanagement doomed the relief efforts.

New divisions arrived in Basra in early 1916. But they couldn't be deployed to relieve Kut due to supply problems. Nixon was eventually sacked for his poor logistics.

Goltz died of typhoid before the siege ended. The British lost 26,000 men trying to break the siege. Townshend refused to try to break out of Kut. He believed it was up to the relief force to break in.

During the siege, Townshend showed great self-interest. He worried about his dog, Spot, more than his starving men. He never visited the hospital. He spent his time writing messages and reading military history.

He was upset when a lower-ranked officer replaced Aylmer. Townshend grew desperate. He claimed that if Kut fell, it would be worse than Yorktown. He believed it would lead to the end of the British Empire.

In April 1916, Townshend tried to bribe the Ottomans to let his men leave. Halil Pasha refused. Townshend's garrison was starving.

On April 29, 1916, Townshend surrendered Kut-al-Amara. The 6th Division was captured. During the siege, 1,746 men had died.

Townshend's main concern during surrender was his dog, Spot. Halil Pasha promised to send Spot back to Britain, and he did. Townshend found it humiliating to surrender to a Turkish Muslim.

The news of Kut's fall brought sadness in Britain. It brought joy in the Ottoman Empire. The German Emperor Wilhelm II praised the victory.

A Prisoner of War's Life

On May 2, 1916, Townshend was taken to Baghdad. His men cheered him as he passed. It was the last time most of them saw him.

The Ottoman forces forced the British and Indian prisoners on a brutal "death march." They were deprived of water, food, and medical care. Many died. Only 30% of the prisoners survived.

In contrast, Townshend and his officers were treated well. Only one officer chose to go on the death march with his men. Townshend was taken to Constantinople (Istanbul). He was greeted by General Enver Pasha.

During his journey, Townshend saw his starving men on the death march. He only mentioned it once to Enver. This was his only expressed concern for his men.

He lived comfortably on an island called Prinkipo. He became friends with Enver Pasha. They spoke in French. Townshend was quoted in Ottoman newspapers praising Enver Pasha. He was even given a Turkish naval yacht.

In 1917, while still a prisoner, he received a high honor. He became a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath. Townshend tried to get his wife to join him. But she refused, warning him that enjoying captivity would hurt his image.

Townshend was upset to learn his cousin had a son. This meant he would not inherit the family title.

The Ottoman state committed terrible acts against Armenian and Assyrian minorities. Townshend's good treatment helped the Ottomans with public relations. His praise for Enver Pasha distracted from these atrocities.

At the end of the war, Townshend was involved in surrender negotiations. But Field Marshal Allenby later said Townshend exaggerated his role.

After the War

Townshend returned to England in 1919. He expected a hero's welcome, but only his family and dog greeted him. He asked for a major promotion but was refused. The Army made it clear his career was over.

He resigned from the British Army in 1920. He published his war memoir, My Campaign in Mesopotamia.

After the war, Britain wanted to try Ottoman leaders for war crimes. This included those responsible for the death march of Kut prisoners. Townshend had become friendly with Enver Pasha. He said he would testify for the defense if Enver were tried. This did not help his image in Britain.

Townshend entered politics. He was elected as an Independent Conservative Member of Parliament in 1920. He spoke on Middle East affairs.

However, reports surfaced about the terrible suffering of his men as POWs. Townshend's heroic reputation faded. Military experts criticized his actions at Ctesiphon and Kut. He did not seek re-election in 1922.

He offered to help mediate between Britain and Turkey. But the British government declined. He visited Kemal Atatürk in Turkey in 1922 and 1923.

Sir Charles Townshend died of cancer in Paris in 1924, at age 63. He was buried with military honors.

Personal Life and Family

On November 22, 1898, Townshend married Alice Cahen d'Anvers. Alice was famously painted as a child by Renoir in his 1881 portrait Pink and Blue.

They had one daughter, Audrey Dorothy Louise Townshend. She married Count Baudouin de Borchgrave d'Altena. The journalist Arnaud de Borchgrave was Sir Charles Townshend's grandson.

His niece, Tiria Vere Ferrers Townshend, survived the sinking of the RMS Empress of Ireland in 1914. She was one of only 41 women to survive. Her aunt, who was with her, was lost.

Lady Townshend lived for more than 40 years after her husband. She died at age 89.

Images for kids

| William M. Jackson |

| Juan E. Gilbert |

| Neil deGrasse Tyson |