Coastal GasLink Pipeline facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Coastal GasLink Pipeline |

|

|---|---|

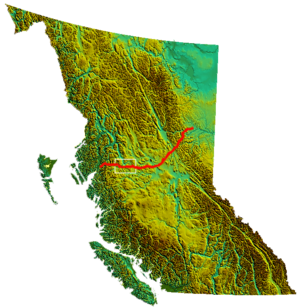

Coastal GasLink route.

Wetʼsuwetʼen territory is in the white square |

|

| Location | |

| Country | Canada |

| Province | British Columbia |

| From | Dawson Creek, British Columbia |

| To | Kitimat, British Columbia |

| General information | |

| Type | Natural Gas |

| Owner | TC Energy |

| Partners | LNG Canada, Korea Gas Corporation, Mitsubishi, PetroChina, Petronas |

| Construction started | 2019-2020 |

| Technical information | |

| Length | 670 km (420 mi) |

The Coastal GasLink pipeline is a large TC Energy natural gas pipeline being built in British Columbia, Canada. It starts near Dawson Creek and travels about 670 kilometers (416 miles) through mountains to Kitimat. In Kitimat, the natural gas will be cooled and turned into liquefied natural gas (LNG). This LNG will then be shipped to customers in Asia.

The pipeline route crosses traditional lands of several Indigenous peoples. Some of this land is "unceded." This means it was never given up by treaties to the Canadian government. The project has caused disagreements among Indigenous leaders. Elected band councils, set up by the 1876 Indian Act, often support the project. However, the traditional Wetʼsuwetʼen hereditary chiefs oppose it. They worry about the environment and have organized blockades to stop construction on their traditional land.

Courts have issued orders, called injunctions, against protesters blocking the project. These orders were given by the BC Supreme Court in 2018 and 2019. In 2019 and 2020, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) entered the blocked areas. They cleared roads for construction, arresting several land defenders. These arrests in 2020 led to widespread protests across Canada. People protested at government offices, ports, and rail lines. For example, in February 2020, Mohawk First Nation people in Tyendinaga, Ontario, blocked a key railway. This caused Via Rail to stop many passenger trains. Canadian National Railway (CNR) also stopped freight service in eastern Canada for several weeks.

Coastal GasLink (CGL) continued building after the RCMP cleared the Wetʼsuwetʼen blockades. But the Wetʼsuwetʼen hereditary chiefs still oppose the pipeline. They even asked CGL to stop construction during the COVID-19 pandemic. They were worried about spreading the disease. Construction mostly continued, though the government issued some stop-work orders in June 2020. This happened after an environmental review. When CGL tried to drill under the Wedzin-kwa river, more conflict happened. Wet'suwet'en defenders set up new blockades and damaged construction equipment. These blockades were removed in November 2021. By September 2022, CGL was ready to drill under the river. The company said they had finished eight of ten river crossings. They were also nearly 70% done with the whole project.

Contents

What is the Coastal GasLink Pipeline?

The Coastal GasLink pipeline starts near Dawson Creek. It runs about 670 kilometers (416 miles) southwest to a plant near Kitimat. This plant will turn the natural gas into liquefied natural gas (LNG). The LNG will then be sold to other countries. The company expects to sell most of it to Asian nations. These nations plan to switch from coal power plants to natural gas.

The pipeline crosses lands of several Indigenous peoples. This includes the Wet'suwet'en. The traditional Wet'suwet'en government does not agree to the pipeline. The RCMP has removed Wet'suwet'en people from their land multiple times for construction.

The pipeline was first expected to cost about $6.6 billion Canadian dollars. The company TC Energy owns and operates the project. In 2012, LNG Canada chose TC Energy to design, build, and own the pipeline. By July 2022, about 70% of the pipeline was finished. The cost had increased to $11.2 billion Canadian dollars.

Who Supports and Opposes the Pipeline?

The pipeline project has both supporters and opponents.

Why Do People Oppose the Pipeline?

The hereditary chiefs of the Wetʼsuwetʼen oppose the project. Other First Nations and environmental groups also oppose it.

Hereditary chiefs say they have authority over their traditional Wet'suwet'en territory. They believe elected band councils, created by the Indian Act, only have power over reserves. They point out that 22,000 square kilometers (8,500 square miles) of Wetʼsuwetʼen territory was never given to the Government of Canada. The province of British Columbia did not sign treaties with the Wetʼsuwetʼen people. So, the chiefs say their traditional land rights have not been taken away. The Supreme Court of Canada supported these land claims in a 1997 decision.

Hereditary chief Freda Huson helps organize the Unistʼotʼen Camp. This is a protest camp and healing center in Northern BC. She says, "Without our land, we aren't who we are. The land is us and we are the land." She also feels the energy industry just wants to "take, take, take."

Others oppose the pipeline because of environmental concerns. Burning the natural gas from the pipeline creates a lot of carbon dioxide. This is a greenhouse gas that contributes to climate change. In 2018, an environmental activist challenged the pipeline's approval. He wanted a full review by the federal energy board. But the board said the project was under British Columbia's control. The pipeline might also harm Wet’suwet’en waterways. A Gidimt’en clan chief, Sleydo’, said the river is "so clear that you can see these very deep spawning beds that the salmon have been returning to for thousands of years." Construction activities near rivers, like blasting, could harm fish.

Who Supports the Pipeline?

Some Indigenous groups support the pipeline. The First Nations Liquefied Natural Gas Alliance disagreed with officials who called for construction to stop. They said these officials did not talk to Indigenous groups who support the pipeline. The Alliance highlighted opportunities for Indigenous businesses. They also mentioned "extensive" talks with Indigenous people.

Crystal Smith, chief counsellor of the Haisla Nation, supports the project. Her nation signed an agreement for the pipeline to cross their land. She said, "First Nations have been left out of resource development for too long." She added that they are involved and will ensure benefits for all First Nations. Victor Jim, an elected chief of the Wetʼsuwetʼen, also signed a benefits deal.

In February 2020, 200 Wetʼsuwetʼen community members attended a pro-pipeline meeting. Robert Skin, a councillor with the Skin Tyee First Nation, said the project "will look after our children." He criticized protesters for stopping traffic and railroads. Paul Manly, a Green Member of Parliament, suggested that elected councils did not truly "consent." He felt they just "conceded" because the project seemed unavoidable.

The project and protests showed disagreements within the Wetʼsuwetʼen and Mohawk First Nations. Wetʼsuwetʼen hereditary chiefs opposed the project. But elected band councils supported it. This led to calls for a "cohesive voice." The railroad blockade by the Tyendinaga Mohawks in February 2020 was not organized by their band leadership. The Haudenosaunee Confederacy condemned the "RCMP Invasion." Hereditary chiefs thanked Mohawk communities for their support. But they met with a different Mohawk government group. Grand Chief Serge Otsi Simon of the Kanesatake Mohawk First Nation asked protesters to end the rail blockades. He said it would show compassion and that their point had been made.

Pipeline Project History

How Were People Consulted?

Consultations with local band councils happened between 2012 and 2014. After a 1997 court case involving the Gitxsan and Wet'suwet'en peoples, talks with hereditary chiefs are also needed. This is for big projects on traditional lands.

The Office of the Wet'suwet'en suggested other routes for the pipeline. These routes would go through areas already disturbed by other projects. Coastal GasLink rejected these ideas in 2014. They said the routes were not good for the pipeline's size. They were also too close to towns and would take longer to plan. Coastal GasLink said their chosen route was the best and caused the least environmental harm. The company says it has held over 120 meetings and 1,300 calls/emails with hereditary chiefs. But they still have not agreed on a route.

How Was the Project Approved?

Twenty elected First Nation band councils approved the project. This included the Wetʼsuwetʼen elected band council. The Government of British Columbia also approved it.

TC Energy announced it would give $620 million Canadian dollars in work to northern B.C. First Nations. The BC Environmental Assessment Office approved the pipeline in 2014. The project received all needed permits from the BC Oil and Gas Commission between 2015 and 2016.

What About the Protests?

Protests started with Wetʼsuwetʼen hereditary chiefs and other land defenders. They blocked access to pipeline construction camps. On January 7, 2019, the RCMP removed blockades after CGL got a court order. They arrested several Wetʼsuwetʼen land defenders. The Wetʼsuwetʼen and RCMP later made an agreement to allow access. But blockades were rebuilt.

In February 2020, the RCMP again removed blockades and arrested defenders. This led to solidarity protests across Canada. Many protests blocked railway lines. This included the main CNR rail line in Eastern Ontario. Passenger and freight trains were stopped for weeks. This caused goods to be rationed and major ports to shut down.

Wetʼsuwetʼen protesters blocked the Morice Forest Service Road. This road leads to the pipeline construction site. The first court order was issued in December 2018. The RCMP set up a temporary office to enforce it. This order was extended in December 2019. The hereditary chiefs then ordered the RCMP and Coastal GasLink to leave.

On February 6, the RCMP started enforcing the order. They arrested 21 protesters at camps between February 6 and 9. The largest camp is Unistʼotʼen Camp, which started in 2010. Arrested protesters included organizers Karla Tait, Freda Huson, and Brenda Michell. All were released within two days. The RCMP also stopped some reporters, affecting freedom of the press. The Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs said they were "in absolute outrage." They felt the Wetʼsuwetʼen people's rights were being "brutally trampled on."

On February 11, 2020, the RCMP said the road was clear. TC Energy announced work would restart. On February 21, the British Columbia Environmental Assessment Office (EAO) told Coastal GasLink to stop construction in a blocked area. They had to talk with the Wetʼsuwetʼen for 30 days. The RCMP closed their local office after hereditary chiefs made it a condition for talks.

Protests supporting the Wetʼsuwetʼen hereditary chiefs happened across Canada. On February 11, protesters surrounded the BC Legislature in Victoria. They stopped ceremonies and made it hard for lawmakers to enter. Other protests happened in Nelson, Calgary, Regina, Winnipeg, Toronto, Ottawa, Sherbrooke, and Halifax.

Other First Nations and activists targeted railway lines. Near Belleville, Ontario, Mohawks blocked a Canadian National Railway line. This caused Via Rail to cancel trains on major routes. This line is very important for CNR in Eastern Canada. Other protests blocked Via Rail lines in Prince Rupert and Prince George. Protests west of Winnipeg blocked the only trans-Canada passenger rail route. Protests also disrupted local train lines in Toronto and Montreal. The Société du Chemin de fer de la Gaspésie freight railway was blocked in Quebec. These nationwide blockades caused Via Rail and CNR to shut down most service for weeks. Regular service returned by early March.

Talks with the government led to an agreement on land rights. This was between the Canadian government, the BC government, and the Wetʼsuwetʼen chiefs. However, this agreement did not address the pipeline. Construction and opposition by the Wetʼsuwetʼen have continued.

Protests in 2021

Construction of the CGL pipeline continued in 2021. Land defenders kept trying to stop construction directly.

In September, at least two people were arrested. Land defenders built blockades and chained themselves to machinery. This was at a drill site where CGL was preparing to drill under the Wedzin Kwa River.

In October, land defenders took a CGL excavator. They also removed construction workers from Wet'suwet'en territory.

On November 13, members of the Gidimt'en clan removed construction workers. When workers refused to leave, land defenders took an excavator. They also damaged a road and blocked a bridge. Defenders criticized the RCMP for past police actions.

Protests in 2022

On February 17, 2022, about twenty masked attackers forced nine workers to leave a work site near Houston, British Columbia. They also attacked and injured RCMP officers. Damage was estimated to be "in the millions of dollars."

What About Non-Compliance Orders?

Coastal GasLink has received several "non-compliance orders." These orders mean they did not follow rules. This has stopped construction in some areas. In 2019, they got an order for starting work without telling trapline hunters.

In spring 2020, Wetʼsuwetʼen groups told the BC Environmental Assessment Office (EAO) that CGL had damaged wetland areas. The EAO found that the company did not follow its wetland plan in 42 areas. They issued a non-compliance order on June 16. Another order was given that day for not protecting endangered Whitebark Pine trees. A third order was issued on June 22, 2020. This was for clearing wetlands without proper environmental surveys. These orders stopped construction within 30 meters of wetlands. The EAO also issued an order about dirty water going into Fraser Lake, which has fish. CGL's own reports have also shown rule violations.

Court Challenge to Environmental Approval

On October 1, 2020, a hearing began in the BC Supreme Court. The Office of the Wet’suwet’en asked the court to reject the EAO's decision. The EAO had extended CGL's environmental approval for five years. Lawyers for the Wet’suwet’en argued that the EAO did not properly consider the pipeline company's history of not following rules. The EAO said there was no reason for the court to review their decision.

In April 2021, the B.C. Supreme Court ruled that the Wet'suwet'en's concerns were not valid. The court approved the extension of CGL's environmental certificate.

See also

- Enbridge Northern Gateway Pipelines

- Trans Mountain Pipeline

- Tsilhqot'in Nation v British Columbia

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |