Compendium ferculorum, albo Zebranie potraw facts for kids

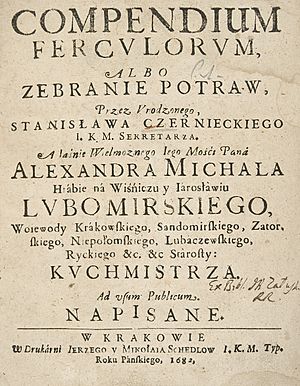

Title page of the first edition, 1682

|

|

| Author | Stanisław Czerniecki |

|---|---|

| Country | Poland |

| Language | Polish |

| Subject | Cookbook |

| Publisher | Drukarnia Jerzego i Mikołaja Schedlów (Jerzy and Mikołaj Schedels' Print Shop), Kraków |

|

Publication date

|

1682 |

| Pages | 96 (first edition) |

Compendium ferculorum, albo Zebranie potraw (which means A Collection of Dishes) is a very old cookbook written by Stanisław Czerniecki. It was first printed in 1682. This makes it the earliest known cookbook originally published in the Polish language. Czerniecki wrote this book while working as the main chef for the powerful Lubomirski family. He dedicated it to Princess Helena Tekla Lubomirska. The book contains more than 300 recipes. These are split into three main parts, with about 100 recipes in each.

The book's chapters cover meat, fish, and other dishes. Each chapter ends with a special "master chef's secret" recipe. Czerniecki's cooking style, shown in his book, was typical of the rich Polish Baroque period. This style still had older, medieval ideas, but it was slowly starting to use new cooking ideas from France. His recipes often used a lot of vinegar, sugar, and interesting spices. They also focused on making food look amazing rather than saving money.

The book was printed many times during the 1700s and 1800s. Sometimes it even had new titles. It had a big impact on how Polish cuisine developed. It also inspired a famous scene in Pan Tadeusz, Poland's national epic poem. This scene describes an old Polish feast.

Contents

Discovering an Old Polish Cookbook

Stanisław Czerniecki was a common person who became a nobleman. He worked for three generations of the powerful Lubomirski family. He was their property manager and main chef. He started working for them around 1645. First, he worked for Stanisław Lubomirski. Then, he worked for Stanisław's son, Aleksander Michał Lubomirski. Finally, he worked for Aleksander Michał's grandson, Józef Karol Lubomirski. Even though Czerniecki's book was printed in 1682, he likely finished writing it before Aleksander Michał Lubomirski died in 1677.

Compendium ferculorum was published about 30 years after a French cookbook called Le Cuisinier françois (The French Cook). This French book, published in 1651 by François Pierre de La Varenne, started a big change in cooking across Europe. French cooking began to use local herbs instead of many exotic spices. The goal was to bring out the natural taste of the food. Rich Polish families often hired French chefs. Some even had copies of Le Cuisinier françois in their libraries. King John III Sobieski, who was married to a Frenchwoman, had one too.

Czerniecki's book, written in Polish, promoted traditional Polish cooking. This style was still quite old-fashioned. His book can be seen as a way to stand up for Polish traditions against the new French cooking ideas.

What's Inside the Book

Title and Dedication

The book's title is in two languages: Latin and Polish. Compendium ferculorum and zebranie potraw both mean "a collection of dishes." The Polish word albo means "or." So, the full title means "A Collection of Dishes, or A Collection of Dishes."

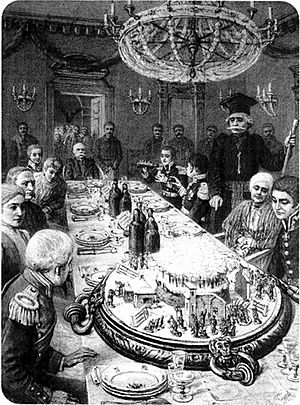

The book starts with Czerniecki dedicating it to Princess Helena Tekla Lubomirska. He calls her his "most kind lady and helper." He mentions a famous feast her father, Prince Jerzy Ossoliński, gave for Pope Urban VIII in Rome in 1633. Ossoliński's trip was known for being very fancy and showing off how grand and rich the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was. He even put loose golden horseshoes on his horse. They fell off as he entered Rome, showing off his wealth even more.

In the dedication, Czerniecki said he had already worked for the Lubomirski family for 32 years. He also mentioned Helena Tekla's husband and son, wishing them good health.

Czerniecki knew his book was the first cookbook in Polish. He wrote, "No one before me has wanted to share such useful knowledge in our Polish language. So, I have dared... to offer the Polish world my compendium ferculorum, or collection of dishes." Some people thought an older Polish cookbook existed, but no copies have survived. So, Czerniecki's work is definitely the oldest known cookbook originally published in Polish.

Kitchen Inventory

After the dedication, there's a detailed list. It includes all the food items, kitchen tools, and staff needed to host a big feast. The food list starts with meats from farms and wild game birds. It also lists different grains and pasta. Then come fruits and mushrooms, both fresh and dried. The vegetable list includes some old vegetables like cardoon and Jerusalem artichoke. Under "spices," Czerniecki lists things like saffron, black pepper, ginger, and cinnamon. But he also includes powdered sugar, rice, raisins, and citrus fruits like lemons and oranges. Even smoked ham and beef tongue are listed as seasonings!

Chef's Advice

Czerniecki then shares his thoughts and advice for the kuchmistrz, or "master chef." He was very proud of being a chef. He saw himself as an artist and a teacher for younger cooks. He believed a good chef should be "clean, sober, watchful, loyal, and most of all, kind to his lord and quick."

He wrote that a chef should be "neat and tidy, with good hair, well-combed, short at the back and sides. He should have clean hands, trimmed fingernails, and wear a white apron. He should not argue, be sober, obedient, and quick. He should understand flavors well and know his ingredients and tools. He should also be willing to serve everyone."

Czerniecki ended these notes by saying not to sprinkle food with bread crumbs. He also promised to focus on "Old Polish dishes." This was so readers could experience local cooking before trying foreign foods.

How the Book is Organized

The main part of the book is well-structured. It has three chapters. Each chapter has 100 numbered recipes. After these, there's an appendix with ten more recipes. Then, there's an extra special recipe called a "master chef's secret." So, each chapter seems to have 111 recipes, making a total of 333.

The first chapter is about meat dishes. It starts with a recipe for "Polish broth." The second chapter has fish recipes. This even includes beaver tail, which was considered a fish for religious reasons. The last chapter is more varied. It has recipes for dairy dishes, pies, tarts, cakes, and soups.

| Chapter 1 | Chapter 2 | Chapter 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Opening | 16 kinds of broth (listed, but without recipes) | 5 recipes for thick sauces for fish dishes (not counted in total) | |

| Main Part | 100 recipes for meat dishes | 100 recipes for fish dishes | 100 recipes for dairy dishes, pies, tarts and cakes |

| Appendix | 10 recipes for French potage (soups) and cold starters; 10 recipes for sauces for roast meat (not counted) |

10 recipes for fish marinades, escargots, turtles, oysters and truffles | 10 recipes for charcuterie (cured meats), smoked fish and mustard |

| Master Chef's Secret | Whole capon (a type of chicken) in a bottle | Whole pike that is partly fried, partly boiled and partly baked | Broth with pearls and a gold coin for sick people |

| Total Recipes | 100 + 10 + 1 | 100 + 10 + 1 | 100 + 10 + 1 |

| 333 | |||

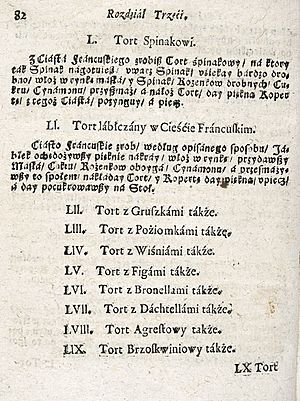

The actual number of recipes is a bit different from what the author claimed. Sometimes, one numbered heading has more than one recipe. For example, under number 4 in chapter 1, there are three different recipes. Other times, a numbered heading doesn't have a recipe at all. It just says that different dishes can be made using the same basic method. For example, in chapter 3, after the apple tart recipe, there are eleven headings like "pear tart likewise" or "sour cherry tart likewise." This means you can make those tarts the same way as the apple tart.

How Czerniecki Cooked

Writing Style

The instructions in Compendium ferculorum are short and often not very clear. They don't list ingredients, measurements, or cooking times like modern recipes. This is because they were meant for a professional chef, not someone new to cooking. The recipe for stewed meat in saffron sauce is a good example:

Take a hazel grouse or a partridge, small birds or pigeons, a capon or veal, or whatever [kind of meat] you want. Soak it in water, put it in a pot, add salt, and bring to a boil. Debone it, cover it again with the broth, and add parsley. When it's boiling, add thick sauce, vinegar, sugar, saffron, pepper, cinnamon, both kinds of raisins, and limes. Bring to a boil and serve in a bowl.

All recipes are written as commands, like "Take this" or "Add that." This way of writing was probably meant for the head chef to read aloud to younger kitchen staff. They would then follow the instructions. This is different from how cookbooks were written later, which used more general language.

Cooking Style

Czerniecki's cooking style, as shown in his book, was about rich, fancy meals. It was also about making food look amazing and having strong, contrasting flavors. When it came to spending, the author warned against wasting food but also against being too cheap.

An old saying goes, it's better to lose a thaler (an old coin) than to be embarrassed by being too cheap. A skilled chef should remember this, so he doesn't shame his lord with foolish saving.

A big feast was meant to impress guests and show off the host's wealth. Using lots of expensive spices was one way to do this. Black pepper, ginger, saffron, cinnamon, and nutmeg were added to most dishes in large amounts. Czerniecki even considered sugar a spice and used it that way. His book has few dessert recipes, but sugar is used a lot in meat, fish, and egg dishes. Vinegar was also used in huge quantities. This mix of very spicy, sweet, and sour tastes was typical of old Polish cooking. Czerniecki called it "saffrony and peppery." Modern Poles would probably find these tastes very unusual today.

The greatest cooking success was a dish that surprised or puzzled the diners. The "secrets" at the end of each chapter are examples of such recipes. One secret is for a capon (a type of chicken) in a bottle. The trick was to skin the bird, put the skin inside a bottle, fill it with a mix of milk and eggs, and boil the bottle. As the mixture heated up, it expanded, making it look like a whole capon was inside the bottle! Another "secret" is a recipe for a whole pike fish that is partly fried, partly baked, and partly boiled. The last recipe is for a broth boiled with pearls and a gold coin. This was supposed to cure sick people and those who had "given up hope for their health."

Czerniecki wanted to show "Old Polish dishes" rather than foreign ones. However, he did mention foreign influences, especially from French cuisine and "Imperial cuisine" (cooking styles from Bohemia and Hungary). He had mixed feelings about French cooking. He thought French potage (creamy soups) were not Polish. He also didn't like using wine in cooking. He wrote, "Every dish can be cooked without wine; it's enough to season it with vinegar and sweetness."

But Czerniecki did include recipes for French soups, dishes with wine, and other French ideas like puff pastry. He argued that a good chef must be able to cook dishes for foreign visitors. In fact, he included more French recipes than he admitted. Even his "secret" capon in a bottle recipe was adapted from a similar one in Le cuisinier françois.

The Book's Lasting Impact

On Cooking

For over 100 years after it was first printed, Compendium ferculorum was the only cookbook in Polish. A new Polish cookbook, Kucharz doskonały (The Perfect Cook), wasn't published until 1783. This new book was mostly a shorter translation of a popular French cookbook. However, one part of Kucharz doskonały was directly based on Czerniecki's work. The author of Kucharz doskonały added his own list of cooking terms, which explained terms (and sometimes whole recipes) from Compendium ferculorum.

So, Kucharz doskonały mixed French cooking, which was becoming popular, with old Polish cooking from Czerniecki's book. Later editions of Kucharz doskonały added even more old Polish and German recipes. This blend of national traditions and new French cooking helped create modern Polish cuisine.

On Literature

In 1834, Compendium ferculorum inspired Adam Mickiewicz to write about "the last Old Polish feast" in Pan Tadeusz. This long poem is set in 1811–1812 and is considered Poland's national epic. In his description of a fictional feast, Mickiewicz included names of dishes from Czerniecki's cookbook, like "royal borscht". He also included two of the master chef's secrets: the broth with pearls and a coin, and the three-way fish.

To show that the feast was from an old, lost world, Mickiewicz added a list of random dishes and ingredients. He found their names in Compendium ferculorum. These foods were already forgotten in his time. This list included things like kontuza (a soup of boiled meat), arkas (sweet milk jelly), and blemas (blancmange). He also listed various fish names from Czerniecki's book. A description of a chef in a white apron and a mention of Prince Ossoliński's banquet in Rome were also inspired by Czerniecki's book.

It's interesting that Mickiewicz seemed to mix up the title of Czerniecki's book with Kucharz doskonały. This happened in the poem and in his notes. We don't know if this was a mistake or if he did it on purpose. A friend of the poet said Mickiewicz always carried an "old and torn book" called Doskonały kucharz. Some historians think it was actually Czerniecki's book, but it was missing its title page. So, Mickiewicz knew the recipes but not the exact title.

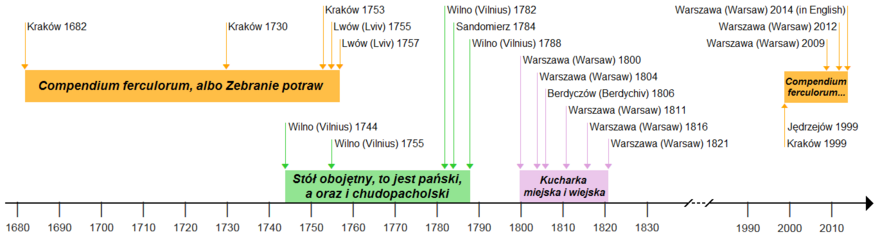

How the Book Was Published

The first edition in 1682 was the only one published during Czerniecki's lifetime. But after he died, Compendium ferculorum was printed about 20 more times until 1821. Some later editions had new titles. This showed that more and more people were reading the book.

The second edition, from 1730, was very similar to the first. Both were printed in an old-fashioned style. Later editions used a more modern print style.

The third edition, published in Wilno (now Vilnius, Lithuania) in 1744, was the first printed outside Kraków. It was also the first to get a new title: Stół obojętny, to jest pański, a oraz i chudopacholski (The Indifferent Table, that is, Both Lordly and Common). The 1784 edition was even bigger. It added 40 new recipes for sauces and other foods. These new recipes were copied from another book and were very different from Czerniecki's original style. They didn't appear in later editions.

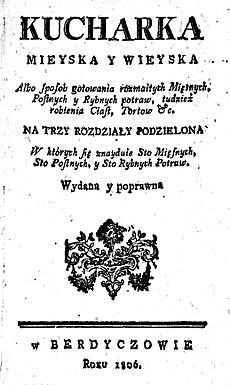

Editions from the early 1800s used yet another title: Kucharka miejska i wiejska (The Urban and Rural [female] Cook). These title changes show that the cooking style of the Lubomirski family's chef, which started in a rich court, eventually became part of everyday cooking for housewives in towns and the countryside across Poland.

Today, people are again interested in old Polish cooking. This has led to new reprints of the book since the year 2000. In 2009, the Wilanów Palace Museum in Warsaw published a special edition. It included a lot of information about Czerniecki's life and work from a food historian.

List of Editions

- 1682: Compendium ferculorum, albo Zebranie potraw (1st ed.)

- 1730: Compendium ferculorum, albo Zebranie potraw (2nd ed.)

- 1744: Stół obojętny, to jest pański, a oraz i chudopacholski (3rd ed.)

- 1784: Stół obojętny, to jest pański, a oraz i chudopacholski (Sandomierz ed.)

- 1806: Kucharka miejska i wiejska (Warsaw ed.)

- 2002: Compendium ferculorum (Limited bibliophile edition)

- 2009: Compendium ferculorum (Wilanów Palace Museum critical edition)

- 2014: Compendium ferculorum (English translation of Wilanów edition)

Translations

In the late 1600s, Compendium ferculorum was translated into Russian. This translation was never printed and only exists as a handwritten copy. In 2014, an English version of the Wilanów edition was published. A French translation is also planned.