Dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire facts for kids

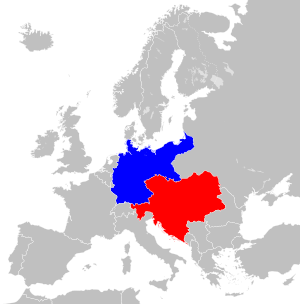

The Holy Roman Empire was a huge collection of lands and states in Central Europe that lasted for over 1,000 years. It was led by an emperor who was seen as the most important ruler in Europe, a bit like a successor to the ancient Roman Empire. But by the 18th century, the empire was often called "sick" because it didn't have a strong central army or treasury, and its emperors didn't have much real power over all the different states within it.

The empire finally came to an end on 6 August 1806. This happened when the last Holy Roman Emperor, Francis II, gave up his title. He also freed all the states and officials from their promises to the empire. This big change was mainly caused by the French Revolutionary Wars and the Napoleonic Wars, especially after Napoleon became very powerful in France.

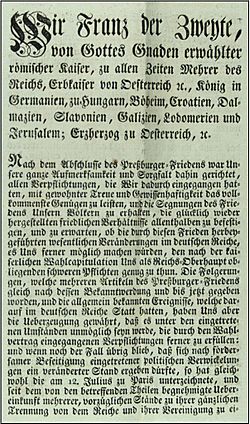

Printed version of the abdication of Emperor Francis II.

|

|

| Date | 6 August 1806 |

|---|---|

| Location | |

| Participants |

|

| Outcome |

|

In 1804, Napoleon declared himself the Emperor of the French. To keep his family's importance, Francis II then declared himself the Emperor of Austria, while still being the Holy Roman Emperor. This was a way to show that his Holy Roman title was still the most important.

However, Austria lost a major battle called the Battle of Austerlitz in December 1805. After this, many German states that were part of the Holy Roman Empire joined Napoleon to form the Confederation of the Rhine. This group was basically controlled by France. This event meant the Holy Roman Empire was effectively over. Francis II's decision to give up his title and dissolve the empire was also a way to stop Napoleon from becoming the Holy Roman Emperor himself. If Napoleon had taken that title, Francis II would have become his subordinate.

People reacted differently to the empire's end. Some were sad or even horrified, especially in Vienna, the capital of Francis II's family lands. Many people didn't think the emperor had the right to dissolve the whole empire. Some common people even thought the news was a trick by their local rulers. In Germany, some compared the empire's fall to the ancient Fall of Troy, a symbol of total destruction.

Contents

Why the Holy Roman Empire Ended

The Empire's Big Ideas

The Holy Roman Empire was special because its emperor was seen as the top ruler in Europe. People believed the empire was a true continuation of the old Roman Empire. Emperors thought they were the only real emperors in Europe. They even claimed to have power over all Christians, even outside their borders.

This idea of universal power was always more of a dream than reality. The empire never actually ruled all of Christian Europe. The emperor's power came from his role as the highest secular ruler and a defender of the Catholic Church. The empire didn't have one fixed capital or consistent lands. This helped the idea that the emperor's title was universal, not tied to one place.

For a long time, the Holy Roman Empire was very important in European politics. Emperors were seen as heirs to the Roman emperors and top Christian rulers. This often gave them special status over other kings.

Even though emperors were called "Elected Roman Emperor" after 1508, their power still reached beyond the empire's official borders. For example, the kings of Sweden and Denmark were vassals (like loyal subjects) for their German lands until 1806. The Reformation in the 1500s, which led to new Christian religions, made it harder to manage the empire. It also made its "holy" nature less clear.

The Holy Roman Empire and the papacy (the Pope's office) both claimed the right to rule universally. They were seen as the two main pillars of the Christian world. But after the Thirty Years' War ended in 1648, the empire and the papacy became separate. The Pope had no say in the peace talks. This marked the end of the old system where the Pope or Emperor solved international problems.

A big challenge to the emperor's traditional power came from new, strong sovereign states in the 1500s and 1600s. These states believed that a ruler's power only extended to the land they directly controlled. Kings who wanted to be free from the empire claimed they could rule their own lands like an emperor. Some ambitious emperors, like Charles V, tried to combine universal power with actual control. But this threatened the existence of other European countries.

The Empire in the 1700s

By the 1700s, many people thought the Holy Roman Empire was "sick." Historians described it as having an "unusual form of government." It didn't have a standing army or a central treasury. The emperor was elected, not born into the role, and had weak central control. All these things made people think it wasn't a unified German state.

Even so, many people hoped the "sick" empire could be healed and made modern. The early 1800s saw big changes within the empire. After a peace treaty with France in 1801, the empire lost control of lands in the Netherlands and Italy. Powerful German rulers in the north, like the Kings of Prussia, gained more land and power. These changes shook up the empire's old political system. But people at the time thought it was a new beginning, not the end.

The Habsburg dynasty, who ruled the Holy Roman Empire, sometimes focused more on their own family's interests than on the empire's. For example, Emperor Joseph II even thought about giving up his imperial title. He once considered trading his lands in Belgium for Bavaria and giving the imperial title to the Bavarian ruler. However, the empire wasn't necessarily doomed by this. When emperors showed less interest, powerful states within the empire often worked to strengthen German unity.

Despite being called "sick," the empire wasn't in total decline before the French Revolutionary Wars began in the 1790s. In the 1700s, the empire's institutions were actually getting stronger. It offered safety and rights to smaller states when Europe was becoming dominated by big, powerful nations. Because the central government was weak, the states within the empire had a lot of say in their own affairs. The central Reichstag (parliament) helped coordinate responses to threats like France. The empire's courts also helped solve conflicts between states.

Wars with France and Napoleon

Austria's Fight and Responses

The Holy Roman Empire fought well against France at first. But Prussia left the war to focus on its Polish lands, taking its strong army with it. This made things much harder for the empire. The war with France was the main reason the empire eventually fell apart.

The conflict started when France declared war on Emperor Francis II, but only as the King of Hungary. However, many parts of the empire, including powerful figures like the King of Prussia, joined the fight with Francis II. This showed that the idea of the empire was still important in the late 1700s.

Prussia's departure from the war was a turning point. Prussia had been the only real balance to Austria's power within the empire. Without Prussia, Austria was left alone to protect the southern German states. Many of these states then started making their own peace deals with France. When Austria found out, they disarmed the armies of Württemberg and Baden in 1796. This made these states resent the emperor and suggested that Austria could no longer protect its vassals.

After the wars with France, there was a big reorganization of the empire's territory. This was meant to repay princes who had lost land to France. Many church lands were taken over, and states like Bavaria and Baden gained a lot of territory. The most important changes were to the group that elected the emperor. Protestants gained a majority for the first time, which raised doubts about whether Francis II could work with his parliament. Many people at the time felt this reorganization had essentially destroyed the empire.

Napoleon's Coronation

In 1804, Napoleon declared himself "Emperor of the French." The Pope even attended his coronation. Napoleon clearly linked his new title to the old Roman emperors, especially Charlemagne. This worried Francis II because his own title, "Emperor of the Romans," was similar.

Napoleon's coronation caused mixed feelings in the Holy Roman Empire. People were happy that France was a monarchy again, but not that Napoleon chose an imperial title. This raised fears that other rulers, like the Russian Emperor or the British King, might also declare themselves emperors.

Austrian officials quickly realized that if they didn't accept Napoleon's title, war with France would start again. So, they decided to accept him as emperor but still keep their own emperor and empire as the most important. It was decided that Austria would also become an empire. This would keep Austria equal to France, while the Holy Roman Emperor would still be seen as superior to both.

The Austrian Empire

On 11 August 1804, Francis II declared himself Emperor of Austria. He already had an imperial coronation, so he didn't need a new one. This new title was meant to cover all of Francis II's personal lands, like Bohemia and Hungary, whether they were part of the Holy Roman Empire or not. The name "Austria" here referred to the Habsburg family, not just the geographical area.

The title of Holy Roman Emperor remained the most important, above both "Emperor of the French" and "Emperor of Austria." It represented the old idea of a universal Christian empire. The Austrian and French titles were seen more like royal titles because they were passed down through families. In Austria's view, there was still only one true empire and one true emperor in Europe. To show this, Francis II's official title put the Roman title first: "elected Roman Emperor, ever Augustus, hereditary Emperor of Austria."

Napoleon recognized Francis II's new title because he needed Austria's acceptance for his own title to be widely recognized. Other countries like Britain and Russia also recognized it. Only Sweden objected, saying it broke the empire's rules. But other states in the empire agreed to a long break, which stopped the debate.

Peace of Pressburg

Austria went to war with France again in September 1805. But they were badly defeated at the Battle of Austerlitz in December 1805. This forced Austria to sign the Peace of Pressburg on 26 December. This treaty created confusion about the empire's rules.

Bavaria, Baden, and Württemberg were given "full sovereignty" (meaning they were fully independent) but were still part of a "Germanic Confederation," a new name for the Holy Roman Empire. It was unclear if other lands taken by France would remain part of the empire.

The Free Imperial Knights, who were small independent territories, were also attacked and taken over by states allied with Napoleon. Their organization dissolved in January 1806. With the empire's end, these knights lost their special independent status.

People at the time saw the defeat at Austerlitz as a huge turning point in history. The Peace of Pressburg was also seen as a radical change. It seemed to make Bavaria, Baden, and Württemberg equal to the empire, while downgrading the empire itself to just a German confederation.

Forming the Confederation of the Rhine

In early 1806, Bavaria, Baden, and Württemberg tried to stay independent from both the empire and Napoleon. But in April 1806, Napoleon pushed for a treaty. He wanted these three states to be allies with France forever. They would also agree not to fight in future imperial wars. They would still be members of the empire, but under Napoleon's leadership. Württemberg refused to sign this.

In June 1806, Napoleon started pushing Bavaria, Baden, and Württemberg to create a "confederation of upper Germany" outside the empire. On 12 July 1806, these three states and thirteen other smaller German princes formed the Confederation of the Rhine. This group was basically a French-controlled state.

On 1 August, a French representative told the Holy Roman Empire's parliament that Napoleon no longer recognized the empire's existence. On the same day, nine princes from the Confederation of the Rhine announced that the Holy Roman Empire had already fallen apart after the Battle of Austerlitz.

Francis II Gives Up His Title

After Napoleon became "Emperor of the French" in 1804 and Austria lost the Battle of Austerlitz in 1805, the Habsburg family wondered if the Holy Roman Empire was worth defending. Many states that were supposed to serve the emperor had openly sided with Napoleon. Even so, the empire's importance was based on its prestige, not on actual control of resources.

Francis II's main goal in 1806 was to avoid more wars with Napoleon. One big worry was that Napoleon might try to become Holy Roman Emperor himself. Napoleon was fascinated by Charlemagne, an old emperor. He used Roman imperial symbols and wanted to create a new order in Europe, like the universal rule of the Roman emperors. Napoleon saw Charlemagne as a French conqueror who had expanded French rule, which he wanted to do too.

Austria was slow to react to these fast changes. Francis had already decided on 17 June to give up his title when the time was right for Austria. On 22 July, Napoleon gave an ultimatum, demanding Francis abdicate by 10 August. The Austrian government believed giving up the title was unavoidable. They also thought they should dissolve the empire at the same time. This would stop Napoleon from getting the imperial title. If the empire was just left without an emperor, two states allied with Napoleon could have taken over imperial power.

It's not certain if Napoleon actually wanted to be Holy Roman Emperor. He might have thought the title couldn't be combined with "Emperor of the French." But he did tell the Pope in early 1806, "Your Holiness is sovereign in Rome but I am its Emperor."

Giving up the title was also a way for Austria to gain time to recover from its losses. The old Roman title and the idea of a universal Christian monarchy were still respected, but they were also seen as belonging to the past. With the Holy Roman Empire dissolved, Francis II could focus on his new, hereditary Austrian Empire.

On the morning of 6 August 1806, the Holy Roman Empire's herald announced Francis II's official statement in Vienna. Copies were sent to diplomats on 11 August. The statement didn't mention Napoleon's demand. Instead, it said that the way the states interpreted the Peace of Pressburg made it impossible for Francis to fulfill his duties as emperor.

Holy Roman Emperors had given up their titles before, like Charles V in 1558. But Francis II's abdication was unique. Previous emperors gave the crown back to the electors to choose a new emperor. Francis II's abdication dissolved the empire itself, so there were no more electors.

What Happened Next

How People Reacted

Public Reactions

The Holy Roman Empire had lasted for over 1,000 years, so its end was a big deal. Many people in Germany felt anger, sadness, or shame. Even some states that joined Napoleon's Confederation of the Rhine were upset. The Bavarian representative said he was "furious" for signing the "destruction of the German name."

From a legal point of view, Francis II's actions were debated. Experts agreed he could give up his title. But they didn't think he had the power to dissolve the entire empire. So, some states refused to accept that the empire was gone. In October 1806, farmers in Thuringia thought the news was a trick by local authorities. For many, the empire's collapse made them worried about their future and Germany's future. People in Vienna were horrified and found the dissolution "incomprehensible."

However, some thinkers and artists saw Napoleon as bringing a new era, not just destroying the old. Some German nationalists believed the empire's fall freed Germany from old ideas. They thought it paved the way for Germany to become a unified nation 65 years later.

Many people worried about what would protect smaller German states now. The poet Christoph Martin Wieland said Germany had fallen into an "apocalyptic time." He asked, "Who can bear this disgrace, which weighs down upon a nation which was once so glorious?" Some saw the end of the Holy Roman Empire as the final end of the ancient Roman Empire. They compared it to the catastrophic fall of ancient Troy, a symbol of total destruction. The idea of the apocalypse was also used, linking the empire's collapse to the end of the world.

Criticism of the empire's dissolution was often censored, especially in areas controlled by France. Protests soon died down because of French suppression and harsh punishments for those who supported the empire.

Official and International Reactions

Officially, Prussia only expressed regret for the "termination of an honourable bond." Prussia's representative was sad but also grateful to the Habsburg family. He said, "So the emperor whom I helped elect was the last emperor!" The Austrian envoy to Hesse-Kassel reported that the local ruler cried and lamented the loss of "a constitution to which Germany had for so long owed its happiness and freedom."

Internationally, reactions were mixed or indifferent. Russia didn't respond. Denmark officially made its German lands part of its kingdom. King Gustav IV Adolf of Sweden issued a statement to his German subjects. He said the empire's dissolution "would not destroy the German nation." He hoped the empire might be revived.

Could the Empire Be Restored?

Francis II's abdication and the release of his vassals meant the Holy Roman Empire was dissolved. But the title of Holy Roman Emperor and the idea of the empire itself were never officially abolished. The idea of a universal empire, even without land or an emperor, sometimes appeared in the titles of later kings. For example, the Kings of Italy continued to claim a title related to the Holy Roman Empire until 1946.

After Napoleon's defeats in 1814 and 1815, many in Germany wanted to bring back the Holy Roman Empire. They wanted Francis I of Austria to lead it. But several things prevented this. Larger, stronger kingdoms had risen in Germany, like Bavaria and Saxony. Prussia also wanted to be a great power, not a vassal to the Habsburgs.

Even so, restoring the Holy Roman Empire with a new political structure was possible at the Congress of Vienna (1814–1815). This meeting decided Europe's borders after Napoleon's defeat. However, Emperor Francis decided that the old empire's structure wouldn't be better than the new order. He felt restoring it was not in Austria's best interest. The Pope was also upset that the Holy Roman Empire wasn't restored.

Instead of the Holy Roman Empire, the Congress of Vienna created the German Confederation. This group was led by the Austrian emperors but was not very effective. It was weakened by revolutions in 1848–1849. After this, a parliament elected by the people tried to create a new German Empire. They wanted the King of Prussia to be their emperor. But he didn't approve. He preferred to restore the Holy Roman Empire under the Habsburgs.

Successor Empires and Legacy

In the Austrian Empire, the Habsburg family continued to rule. Even though the German states were freed from their duties, Francis II and his successors still ruled many German-speaking people. The Holy Roman Imperial Regalia (crowns and symbols) are still kept in Vienna today. The Habsburg family remained important among European royal families. Many of their subjects still saw them as the only true imperial family. The new Austrian Empire was similar in many ways to the old Holy Roman Empire. Austrian emperors continued to protect the Catholic Church, just like the Holy Roman emperors had.

After Francis II gave up his title, the new Austrian Empire tried to distance itself from the old empire. They changed their symbols and titles to show Austria was a separate entity. They even dropped the word "hereditary" from "Empire of Austria" because it had been used to show the difference from the Holy Roman Empire.

Besides the Austrian Empire and France under Napoleon, the Kingdom of Prussia was another possible successor to the Holy Roman Empire's legacy in Germany. Prussia was a major power in Central Europe during the last century of the Holy Roman Empire. There were often rumors that Prussia wanted to be an empire. But Prussian kings usually said that more land and power were better than the imperial title.

In 1806, Prussia's view changed. They feared Napoleon might claim to be "Emperor of Germany." Plans were made to create an "imperial union" in northern Germany with a Hohenzollern (Prussian) emperor. But these plans were dropped because they didn't have much support. The Prussian rulers didn't see themselves as an imperial family because they lacked imperial ancestors.

Germany was finally united into the German Empire in 1871 under Emperor Wilhelm I of the Hohenzollern family. But the new empire's creation was tricky, and the Hohenzollerns were often uncomfortable with its meaning. They tried to link the German Empire to the Holy Roman Empire. But their emperors still listed themselves after the Kings of Prussia, not after the old Holy Roman Emperors.

Both the German Empire and Austria-Hungary (the Habsburg empire) fell in 1918 after World War I. Over the centuries, the many states of the Holy Roman Empire evolved into the 16 modern states of Germany. These German states, with their local control over things like culture and education, are seen by some as a link back to the old empire. Some historians even compare the Holy Roman Empire to the modern Federal Republic of Germany.

Even though the Holy Roman Empire couldn't stop war with France, its role in working for peace and forming loose partnerships offered a different path. It was an alternative to Napoleon's absolute monarchy and the ideas of revolutionary France. It also served as a model for future international organizations.

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |