Dutch Formosa facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Governorate of Formosa

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1624–1668 | |||||||||||||

|

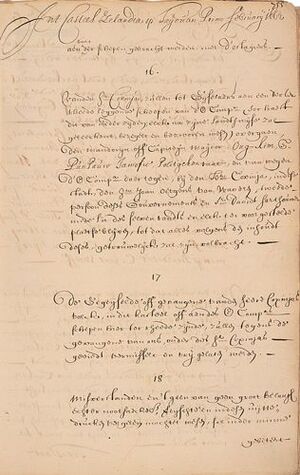

Flag of the Dutch East India Company

Emblem of the Dutch East India Company

|

|||||||||||||

The locations of Dutch Formosa, overlapping a map of the present-day island. Dutch Formosa

Kingdom of Middag

|

|||||||||||||

| Status | Dutch colony | ||||||||||||

| Capital | Zeelandia (now Anping, Tainan) |

||||||||||||

| Official languages | Dutch | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | East Formosan languages • Hokkien | ||||||||||||

| Religion | Dutch Reformed, native animistic religion, Chinese folk religion |

||||||||||||

| Government | Governorate | ||||||||||||

| Governor | |||||||||||||

|

• 1624–1625

|

Martinus Sonck | ||||||||||||

|

• 1656–1662

|

Frederick Coyett | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Age of Discovery | ||||||||||||

|

• Established

|

1624 | ||||||||||||

| 1661–1662 | |||||||||||||

|

• Abandonment of Keelung

|

1668 | ||||||||||||

| Currency | Dutch guilder | ||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

| Today part of | Republic of China (Taiwan) | ||||||||||||

The island of Taiwan, also known as Formosa, was partly controlled by the Dutch Republic from 1624 to 1662, and again from 1664 to 1668. During the Age of Discovery, the Dutch East India Company (VOC) came to Formosa. Their main goals were to trade with China and Japan. They also wanted to stop the Portuguese and Spanish from trading and setting up colonies in East Asia.

The local people and Chinese settlers did not always welcome the Dutch. There were several uprisings that the Dutch military had to put down. Later, the Dutch East India Company joined forces with the new Qing dynasty in China. This helped them get better access to important trade routes. Dutch rule ended after the siege of Fort Zeelandia in 1662. An army led by Koxinga took over the fort, expelled the Dutch, and started the Kingdom of Tungning.

Contents

History of Dutch Formosa

Why the Dutch Came to Formosa

In the early 1600s, the Dutch Republic and England started exploring the world's seas. They soon clashed with Spain and Portugal, who were already powerful. The Dutch were also fighting Spain for their independence in Europe.

The Dutch East India Company (VOC) first tried to trade with China in 1601. But China already traded with the Portuguese in Macau. In 1604, a Dutch fleet tried to attack Macau but was blown off course by a typhoon. They ended up in the Pescadores (Penghu), a group of islands west of Formosa. The Dutch tried to trade with China from there but were unsuccessful.

The Dutch wanted China to open a port for their trade. They also wanted China to kick out the Portuguese. The Dutch even raided Chinese ships to try and force them to agree.

In 1622, after failing to attack Macau again, the Dutch built a base in the Pescadores. They forced local Chinese people to build a fort there. Many workers died because of harsh conditions. China told the Dutch to leave the Pescadores because it was Chinese land. China suggested they go to Formosa instead, where they could trade. This led to a war between the Dutch and China from 1622 to 1624. China won, forcing the Dutch to leave the Pescadores and move to Formosa.

Starting the Colony

In 1624, the Dutch arrived in Taiwan. They found about 1,500 Chinese traders already living there. The Dutch built a temporary fort on a sandy area called Taoyuan. Four years later, they replaced it with a stronger fort, Fort Zeelandia.

The Dutch allied with a local village called Sinkan. In 1625, they bought land from the Sinkanders and built a town called Sakam for Dutch and Chinese merchants. At first, other villages were peaceful. But over time, things changed. In 1629, some Dutch soldiers were ambushed and killed by warriors from Mattau and Soulang villages.

The Dutch sent more soldiers to Taiwan in 1634 and 1635. They defeated Mattau and other villages that had caused trouble. In 1636, a large group of Dutch and their allies went to Liuqiu Island. They trapped about 300 people in caves and killed them. The remaining 1,100 people were taken from the island and enslaved. The Dutch wanted to control the outlying islands and work closely with friendly native groups.

Japanese Trade and Conflicts

Japanese traders were active in Taiwan even before the Dutch arrived. In 1593, Toyotomi Hideyoshi of Japan wanted to control Taiwan. In 1616, a Japanese official sent ships to conquer Taiwan, but a typhoon scattered them.

In 1625, the Dutch tried to stop Japanese trade in Taiwan. The Japanese paid more for Chinese silk, so Chinese merchants preferred them. The Dutch also limited Japanese trade with China. In response, the Japanese took 16 people from the Sinkan village to Japan. A Dutch official named Pieter Nuyts went to Japan to learn about this. The Japanese shogun (military ruler) refused to meet the Dutch.

Nuyts returned to Taiwan before the Sinkanders. He refused to let them land and had them jailed. The Japanese then took Nuyts hostage. They released him only when the Sinkanders were freed and their gifts returned. The Dutch blamed the Chinese for causing trouble with the Sinkanders.

The loss of Japanese trade made the Dutch colony less profitable. The Dutch considered leaving Taiwan. But in 1630, a new shogun allowed the Dutch to talk to him again. Nuyts was sent to Japan as a prisoner until 1636. After 1635, the shogun stopped Japanese people from going abroad. This removed the Japanese threat to the Dutch East India Company.

Piracy and Zheng Zhilong

Europeans sometimes worked with Chinese pirates and sometimes fought them. After a pirate leader named Li Dan died in 1625, Zheng Zhilong became the new pirate chief. The Dutch allowed him to raid ships under their flag.

Chinese officials asked the Dutch for help against Zheng Zhilong. The Dutch agreed, but they failed to stop him. Zheng Zhilong attacked the city of Xiamen, destroying many ships. In 1628, the Chinese government made him an official admiral to fight pirates. He used this power to get rid of his rivals and control trade.

In 1633, the Dutch and their pirate allies launched a surprise attack on Zheng Zhilong's fleet, destroying it. But Zheng quickly built a new fleet. In October 1633, Zheng defeated the Dutch fleet in an ambush. The Dutch then made peace with Zheng, and he helped increase Chinese trade in Taiwan. Zheng Zhilong continued to influence Taiwan's affairs and helped the Chinese population grow there.

Dutch Peace and Spanish Defeat (1636–1642)

After their military campaigns in 1635–1636, more and more villages in Taiwan swore loyalty to the Dutch. This was sometimes out of fear, but also for the benefits like food and safety. This period of relative peace is sometimes called the Pax Hollandica (Dutch Peace).

The northern part of Taiwan was controlled by the Spanish from 1626. They had settlements in Tamsui and Keelung. The Dutch saw the Spanish fort in Tamsui as a major obstacle.

In 1642, the Dutch returned with more soldiers and local warriors. They managed to defeat the Spanish and drive them off the island. After this victory, the Dutch worked to bring the northern villages under their control, just as they had done in the south.

Guo Huaiyi Rebellion (1652)

The Dutch encouraged many Chinese people, mostly from Fujian, to move to Taiwan. Most were young single men. In 1652, a large rebellion led by a Chinese farmer named Guo Huaiyi broke out. It was caused by anger over high taxes and corrupt officials.

On September 7, 1652, Guo Huaiyi gathered an army of farmers armed with bamboo spears and knives. They attacked Sakam the next morning. The Dutch soldiers fought back, scattering the large peasant army. The Dutch also got help from native warriors. Over a few days, about 4,000 Chinese rebels were killed, and Guo Huaiyi's head was displayed.

This rebellion, though easily put down, greatly reduced the number of Chinese farmers. However, thousands more Chinese moved to Taiwan later due to wars in mainland China. The Dutch then tried to limit contact between Chinese and native people.

Trade War and the End of Dutch Rule (1650s–1662)

Zheng Chenggong, also known as Koxinga, was the son of Zheng Zhilong. He became a powerful leader who fought against the Qing dynasty in China. Some Dutch officials thought he might be planning to take Taiwan.

In 1655, Koxinga sent a letter to the Dutch governor, calling the Chinese in Taiwan his subjects. He threatened to stop Chinese trade with Taiwan if the Dutch did not protect his ships. Koxinga's actions caused trade in Taiwan to slow down. Chinese merchants left, and farmers struggled to sell their crops.

In 1661, a Dutch employee named He Bin gave Koxinga a map of Taiwan. On March 23, 1661, Koxinga's fleet, with about 25,000 soldiers, sailed from Kinmen to Taiwan. They landed at the bay of Luermen. Koxinga's forces defeated the Dutch ships and took control of the waters around Taiwan.

On April 4, Fort Provintia surrendered to Koxinga's army. On April 7, Koxinga's army began a siege of Fort Zeelandia. An attack on the fort failed, so Koxinga decided to starve the defenders out. Dutch reinforcements tried to help but failed. In January 1662, a Dutch sergeant defected and told Koxinga about a weak spot in the fort's defenses. On January 12, Koxinga's ships attacked, and the Dutch surrendered. On February 9, the remaining Dutch left Taiwan.

The Dutch held onto Keelung in northern Taiwan until 1668. They tried to retake other parts of the island but failed. Due to resistance from local people and no progress, they finally left Taiwan completely in 1668.

How the Dutch Governed

The Dutch claimed all of Taiwan, but they mostly controlled the plains on the west coast. They also had a few small areas on the east coast. They gained this land between 1624 and 1642. Most villages had to promise loyalty to the Dutch but were largely allowed to govern themselves.

To show their loyalty, village leaders would bring a small plant from their town to the Dutch governor. This meant they were giving their land to the Dutch. In return, the governor gave the leader a special robe, a staff, and a Prinsenvlag (Prince's Flag) to display in their village.

The Governor of Formosa

The Governor of Formosa was the main leader of the Dutch government in Taiwan. He was chosen by the governor-general in Batavia (now Jakarta, Indonesia). The Governor of Formosa could make laws, collect taxes, and declare war or peace for the Dutch East India Company.

He was helped by the Council of Tayouan, a group of important people in the area. The governor lived in Fort Zeelandia. There were 12 governors during the Dutch colonial period.

Economy and Trade

The Dutch trading post in Taiwan became very profitable, second only to their post in Japan. It took 22 years for the colony to start making money. The Dutch benefited from trade between themselves, the Chinese, and the Japanese. They also used Taiwan's natural resources. They introduced a money-based economy and began to develop the island's economy seriously for the first time.

Trade Goods

The main reason for building Fort Zeelandia was to create a base for trading with China and Japan. It also helped them interfere with Portuguese and Spanish trade. Goods like silk from China and silver from Japan were traded.

The Dutch soon realized the value of the many Formosan sika deer on the island. The deer skins were highly valued by the Japanese, who used them for samurai armor. Other deer parts were sold to Chinese traders for meat and medicine. The Dutch paid the local people for the deer they brought. However, the deer population began to decrease, forcing the local people to find new ways to live.

Sugar cane was native to Taiwan, but the local people did not know how to make sugar granules. Chinese immigrants brought this skill. Sugar became the most important export. Taiwan's sugar made more profit than sugar from Java. A lot of sugar was sent to Persia and Japan. Tea was also a major export. Sulfur, found near Keelung and Tamsui, was another important export.

Taiwan, especially Taoyuan, became a key shipping center for trade in East Asia. Products from Japan, China, Vietnam, Thailand, and Indonesia were sent to Taiwan. From there, they were exported to other countries. The Dutch traded amber, spices, pepper, and other goods from Southeast Asia to China and Japan. They also carried silk, porcelain, and gold from China to Japan and Europe.

Farming and Taxes

The Dutch hired Chinese people to grow sugarcane and rice for export. Some of these crops were sent as far as Persia. The Dutch tried to get the local tribes to farm instead of hunt, but this was difficult. Farming was seen as women's work and was very hard.

So, the Dutch brought many Chinese laborers to the island. It's estimated that 50,000 to 60,000 Chinese settled in Taiwan during Dutch rule. The Dutch offered them free travel to the island, tools, oxen, and seeds to start farming. In return, the Dutch took one-tenth of their crops as tax.

The Dutch also collected taxes on imports and exports. They also had a poll tax, which was a tax on every person who was not Dutch and over six years old. This tax increased over time. They also taxed hunting licenses. By 1653, taxes became a very important way for the Dutch to make money in Taiwan.

People of Dutch Formosa

Before the Dutch arrived, Taiwan was mostly home to Taiwanese aborigines. These Austronesian groups lived by hunting and gathering, and also by simple farming. It's hard to know exactly how many native people lived there when the Dutch arrived. Even when the Dutch controlled the most land, large areas were still outside their rule.

Different Groups of People

The population of Dutch Formosa had three main groups: the native aborigines, the Dutch, and the Chinese. There were also some Spanish people in the north between 1626 and 1642. Sometimes, Japanese-Korean trader-pirates called Wakō also operated in coastal areas not controlled by the Dutch.

Native Aborigines

The native Formosan peoples had lived in Taiwan for thousands of years. A Dutch count in 1650 estimated there were between 64,000 and 68,000 aborigines. They lived in villages, with populations from a few hundred to about 2,000. Different groups spoke different Formosan languages that were not easy to understand by others.

A Swiss soldier named Captain Ripon, who was in Taiwan in 1623, wrote about his experiences. He described how he helped build a fort. He also wrote about the native people. He noted that men slept in large round buildings in the center of villages and trained in public squares. He saw headhunting, which happened between harvest and planting seasons. The heads of enemies were kept in these men's houses.

Ripon's group became friends with the people of Bacaloan by giving them small gifts. This angered the neighboring Mattau people, who were described as "like big giants." The Mattau and Bacaloan people later attacked the Dutch fort.

The Dutch

The Dutch group was mostly made up of soldiers. There were also some slaves and workers from other Dutch colonies. The number of soldiers changed depending on the colony's needs. It went from 180 troops at the start to 1,800 just before Koxinga's invasion. There were also traders, missionaries, and teachers. The Dutch brought slaves from other colonies, who mostly served important Dutch people.

After the Dutch were expelled in 1662, some Dutch women were taken as partners by the Chinese. They were never freed.

Chinese Settlers

The Dutch East India Company encouraged Chinese people to move to Taiwan. They offered free land, no taxes, and loans. Sometimes, they even paid Chinese people to move. As a result, thousands of Chinese came to Taiwan to grow rice and sugar. Most were young single men looking for new opportunities or hiding from Chinese authorities. They sometimes called Taiwan "The Gate of Hell" because of its dangers.

The Dutch allowed Chinese people to own land in certain areas. They tried to stop Chinese people from mixing with the native tribes. At first, the Dutch protected the Chinese from the natives. But later, they tried to keep the Chinese from influencing the natives.

Chinese traders sold salt, iron, and clothing to the native people in exchange for meat and hides. The Dutch tried to control the deer skin trade, forcing Chinese hunters to sell only to the company. This led to Chinese hunters moving into native lands where the Dutch had removed the natives.

The Dutch also started taxing the Chinese settlers more. They charged a residency permit tax for all Chinese males. Soldiers checked these permits, and Chinese people could not move without permission. These taxes and restrictions caused protests and discontent among the Chinese.

Taiwanese Natives Under Dutch Rule

Life and Culture

Before the Dutch arrived, Taiwanese aborigines lived in many separate tribes. They had populations ranging from a hundred to a thousand people. A Dutch count in 1650 estimated fewer than 50,000 native people in the plains. These tribes had different languages and ways of life. They were often suspicious of strangers and sometimes practiced head-hunting.

The first native groups the Dutch met were the Sinkang, Backloan, Soelangh, and Mattauw. Their initial relationship with the Dutch was hostile, with several uprisings. The Dutch eventually used a "divide-and-conquer" strategy. They allied with some tribes against others and conquered those who did not cooperate.

After these conflicts, the native aborigines were forced to accept Dutch rule. They were used for various labor activities, especially on sugar cane farms and for deer hunting. By 1650, the Dutch controlled 315 tribal villages with about 68,600 people.

Religion and Education

The Dutch East India Company set up a tax system and schools. These schools taught a romanized (Latin-based) script of aboriginal languages and spread Christianity.

The native Taiwanese religion was mainly animist, meaning they believed in spirits in nature. The Dutch saw some native practices as uncivilized. The Christian Bible was translated into native languages, and Christianity was introduced to the tribes for the first time in Taiwan's history.

The missionaries also set up schools. They taught not only religion but also reading and writing. Before the Dutch, the native people did not have a written language. The missionaries created writing systems for the different Formosan languages using the Latin alphabet.

New Technologies

Taiwan's unique trading resources, like deerskins, venison, and sugarcane, made it a very profitable market for the Dutch. The native people were used as manual labor on sugarcane farms and for hunting.

The Dutch also introduced new farming methods. They taught native tribes how to use more efficient ways of managing crops. This was partly because the land was being used more, and new methods were needed to keep deer and sugar resources from running out. The Dutch also brought oxen and cattle to the island and taught people how to dig wells.

Native People in the Military

Taiwanese aborigines became important for keeping peace during the later years of Dutch rule. The Dutch often hired men from nearby native tribes as soldiers. This helped them quickly increase their numbers during rebellions. For example, during the Guo Huaiyi rebellion in 1652, over a hundred native Taiwanese aborigines helped the Dutch defeat the Chinese rebels.

However, during the siege of Fort Zeelandia by Koxinga, some aboriginal tribes who had been allied with the Dutch turned against them. The Sincan aborigines joined Koxinga after he offered them peace. They then helped the Chinese and killed Dutch people. Other native groups also surrendered to the Chinese, celebrating their freedom from Dutch rule by hunting Dutch people and destroying their Christian schoolbooks.

Legacy and Contributions

Today, you can still see the Dutch legacy in Taiwan. In Anping District of Tainan City, you can find the remains of their Castle Zeelandia. In Tainan City, their Fort Provintia is now the main part of what is called Red-Topped Tower. In Tamsui, Fort Antonio (part of the Fort San Domingo museum) is the best-preserved small fort of the Dutch East India Company anywhere in the world.

The economic policies started by the Dutch also laid the groundwork for Taiwan's modern international trade. The port systems they developed helped begin Taiwan's history as a trading nation.

Perhaps the most lasting impact of Dutch rule is the large number of Chinese people who moved to the island. At the start of Dutch rule, there were only about 1,000 to 1,500 Chinese traders in Taiwan. The Dutch encouraged more Chinese to immigrate to help with farming and trade. By the end of Dutch rule, Taiwan had many Chinese villages with tens of thousands of people. The number of Chinese people on the island was growing much faster than the aboriginal tribes. The Dutch also opened up communication between the Chinese and native Taiwanese, which had not existed before.

The Dutch also introduced the domestic turkey to Taiwan.

Legend of Mermaids

According to Frederick Coyett, a Dutch governor, many people saw mermaids near Fort Zeelandia during Koxinga's attack. People searched for them, but they were gone. This was seen as a sign of coming disaster.

See also

- Dutch pacification campaign on Formosa

- Eighty Years' War

- History of Taiwan

- Landdag