Eiji Tsuburaya facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Eiji Tsuburaya

|

|

|---|---|

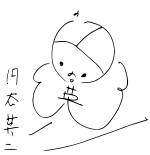

| 円谷 英二 | |

Tsuburaya in 1959

|

|

| Born |

Eiichi Tsumuraya

July 7, 1901 Sukagawa, Fukushima, Empire of Japan

|

| Died | January 25, 1970 (aged 68) Itō, Shizuoka, Japan

|

| Resting place | Catholic Fuchū Cemetery |

| Alma mater | Tokyo Kanda Electrical Engineering School |

| Occupation |

|

| Years active | 1919–1969 |

|

Works

|

Filmography |

| Spouse(s) |

Masano Araki

(m. 1930; |

| Children | 4, including Hajime and Noboru |

| Relatives | Aōdō Denzen (ancestor) Hiroshi Tsuburaya (grandson) |

| Awards | 6 Japan Technical Awards |

| Signature | |

|

|

Eiji Tsuburaya (Japanese: 円谷 英二, Hepburn: Tsuburaya Eiji, July 7, 1901 – January 25, 1970) was a Japanese special effects director, filmmaker, and inventor. He is known as one of the most important people in Japanese movies. He was the genius behind the famous Godzilla and Ultraman series.

People often called him the "Father of Tokusatsu" (special effects) or "God of Monsters" in Japan. He created many new ways to make movies look amazing. Over 50 years, he worked on about 250 films and won many awards.

After a short time as an inventor, Tsuburaya started working for filmmaker Yoshirō Edamasa in 1919. He began as an assistant cameraman. Later, he worked on many films, like Teinosuke Kinugasa's A Page of Madness. When he was 32, Tsuburaya watched King Kong. This movie greatly inspired him to work on special effects. In 1935, he worked on Princess Kaguya, one of Japan's first big movies to use special effects. His first truly successful film for effects was The Daughter of the Samurai (1937). It famously used the first full-scale rear projection in Japan.

In 1937, Tsuburaya joined Toho studio and started their special effects department. He directed the effects for The War at Sea from Hawaii to Malaya in 1942. This film became the highest-earning Japanese movie ever at the time. His amazing effects were a big reason for the film's success. He even won an award for his work. In 1948, Tsuburaya left Toho and started his own company, Tsuburaya Special Technology Laboratory, with his oldest son Hajime. He then worked for other major Japanese studios, creating effects for movies like Daiei's The Invisible Man Appears (1949).

In 1950, Tsuburaya and his effects team officially returned to Toho. At age 53, he became famous worldwide. He won his first Japan Technical Award for his special effects in Ishirō Honda's monster film Godzilla (1954). He continued to direct special effects for many successful science fiction films from Toho. These included Rodan (1956), The Mysterians (1957), Mothra, The Last War (both 1961), King Kong vs. Godzilla (1962), and Mothra vs. Godzilla (1964). King Kong vs. Godzilla became the second-highest-earning Japanese film when it came out. It also restarted the Godzilla series, which is now the longest-running film series ever.

In April 1963, Tsuburaya started Tsuburaya Special Effects Productions. His company later made the TV shows Ultra Q, Ultraman (both 1966), Ultraseven (1967–1968), and Mighty Jack (1968). Ultra Q and Ultraman were very popular when they aired in 1966. Ultra Q made him a household name in Japan. During this time, he also worked on films like The War of the Gargantuas (1966), King Kong Escapes (1967), and the monster movie Destroy All Monsters (1968). Tsuburaya worked on many Toho films and ran his company. However, his health got worse, and he passed away in January 1970.

Contents

Eiji Tsuburaya: Master of Movie Magic

Early Life and Dreams

Childhood and Youth (1901–1919)

Eiji Tsuburaya was born Eiichi Tsumuraya on July 7, 1901. He was born in Sukagawa, Fukushima, where his family ran a business. When he was three, his mother passed away. His father then left the family. Eiji was raised by his grandmother, Natsu. Through her, he was related to a famous painter named Aōdō Denzen. This painter brought Western art to Japan. Tsuburaya believed he got his clever hands from him. His uncle Ichirō was like an older brother to him. Eiji started using the nickname "Eiji" (meaning second-born) instead of "Eiichi" (meaning first-born).

He started elementary school in 1908. People soon saw he was good at drawing. Tsuburaya often dreamed of flying during school. In 1910, he became very interested in flight because Japanese pilots were doing amazing things. Two years later, he started building model airplanes as a hobby. He used a newspaper photo to help him. He loved building models his whole life.

He saw his first movie in 1913. It showed a volcano erupting. Tsuburaya was more interested in the movie projector than the film itself! In 1958, Tsuburaya said he was so fascinated by the projector that he bought a "toy movie viewer." He made his own films by drawing stick figures frame by frame on paper. Because of his early craftwork, he became a local celebrity. A newspaper even interviewed him.

In 1915, at age 14, he finished high school. He really wanted to join the Nippon Flying School. But the school closed in 1917 after its founder died. So, Tsuburaya went to the Tokyo Kanda Electrical Engineering School. While there, he became an inventor for a toy company. He created successful products still used today. His inventions included the first battery-powered phone and an "automatic skate."

Early Career and Marriage (1919–1934)

In 1919, filmmaker Yoshirō Edamasa hired Tsuburaya. Tsuburaya worked as Edamasa's camera assistant on films like A Tune of Pity (1919). He also reportedly wrote screenplays. He worked at the studio until he had to join the Imperial Japanese Army in December 1922.

After leaving the army in 1923, Tsuburaya returned home. He thought about his future in filmmaking. One morning, he left a note saying, "I won't return home until I succeed in the motion picture business, even if I die trying." The next year, he worked as a cameraman on a film. In 1925, Tsuburaya joined Shochiku studio. He had his big break as a cameraman and assistant director on A Page of Madness (1926). Because his films were successful, Tsuburaya became one of Kyoto's top cameramen.

In 1928, Tsuburaya started using new camera tricks. These included double-exposure and slow-motion. The next year, he built his own smaller version of a shooting crane. He used this wooden crane to improve camera movement. It worked well until one day it collapsed, and he fell. A witness named Masano Araki was one of the first to help him. She visited him daily while he was recovering. They soon started a relationship. On February 27, 1930, Tsuburaya married Masano. Their first child, Hajime, was born the next year.

In 1932, Tsuburaya and others started the Japan Cameraman Association. This group later became the Japanese Society of Cinematographers. Soon after, Tsuburaya left Shochiku and joined Nikkatsu Futosou Studios. Around this time, he began using his professional name, "Eiji Tsuburaya."

In 1933, Tsuburaya saw the amazing American film King Kong. This movie inspired him to work on special effects films. He tried to convince Nikkatsu to learn these new techniques. But they were not interested. He managed to get a copy of the film. He studied its special effects frame by frame. He did this without any guides or manuals. In October 1933, Tsuburaya wrote an article about the film's effects.

In the same year, Masano gave birth to their second child, a daughter named Miyako. Sadly, she passed away in 1935. Tsuburaya kept working on projects and improving his camerawork.

In December 1933, Nikkatsu let Tsuburaya use new screen projection technology. He wanted to project films onto real locations. But not all his new ideas were approved. In February 1934, Tsuburaya had a big disagreement with Nikkatsu's CEO. The CEO thought Tsuburaya was wasting money. After the argument, Tsuburaya quit his job at Nikkatsu.

J.O. Studios and Toho (1934–1940)

After leaving Nikkatsu, Tsuburaya joined J.O. Talkies. He researched optical printing and screen projection there. In October 1934, Tsuburaya and his team finished the first iron shooting crane. This crane was on a truck that moved on tracks. This allowed the camera to change position very quickly. The studio was renamed J.O. Studios. Tsuburaya became its chief cameraman in December.

From February to August 1935, he traveled to Hawaii, the Philippines, Australia, and New Zealand. He was directing his first film, Three Thousand Miles Across the Equator. This was a propaganda documentary. During this trip, his second son, Noboru, was born.

When he returned, Tsuburaya started working on Princess Kaguya. This film was based on an old Japanese story. He was the cameraman and also in charge of special effects for the first time. He worked with an animator to create miniatures, puppets, and special scenes. A shorter version of the film was found in 2015. It was shown in Japan in 2021 to celebrate Tsuburaya's 120th birthday.

In March 1936, his first drama film, Folk Song Collection: Oichi of Torioi Village, was released. It was an adventure film with political themes. After this, Tsuburaya worked on The Daughter of the Samurai (1937). This was the first German-Japanese movie. It was Tsuburaya's first big success in effects. It featured the first full-scale rear projection. The German crew was very impressed by his detailed miniature work.

In September 1936, Ichizō Kobayashi combined P.C.L. Studios and J.O. Studios to create Toho studio. A film producer named Iwao Mori knew how important special effects were. So, in 1937, Mori hired Tsuburaya at Toho's Tokyo Studio. He started the special effects department on November 27, 1937, and made Tsuburaya its manager. Tsuburaya then began studying optical printers to create Japan's first version of the device.

Some of Tsuburaya's first films at Toho were The Abe Clan and The Song of Major Nanjo (both 1938). In 1939, he joined the Imperial Army Corps' aviation academy. He was asked to film flight-training movies. He impressed his superiors with his aerial photography.

In November 1939, Tsuburaya became head of Toho's Special Arts Department. A month later, he was asked to film a science movie. In May 1940, Tsuburaya started directing the documentary The Imperial Way of Japan. He also filmed the effects for Navy Bomber Squadron. This film had a bombing scene with a miniature airplane, a first for him. He received his first credit for special effects.

In September 1940, The Burning Sky was released. Tsuburaya was in charge of its effects. He received his first award from the Japan Motion Picture Cinematographers Association. His next film, Son Gokū, was released in November 1940. Tsuburaya said he had to create a "monkey-like monster which was supposed to fly through the air." He added, "I managed the job with some success and this assignment set the pattern for my future work."

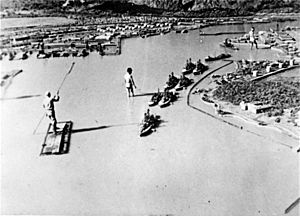

War Years (1941–1945)

On December 7, 1941, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. This made people in Japan feel very proud. The government asked Toho to make a film to encourage the nation. The film, The War at Sea from Hawaii to Malaya (1942), became the highest-earning Japanese film ever. Tsuburaya directed its effects. He used navy photos of the Pearl Harbor attack to help him. His amazing effects were a big reason for the film's success. He won an award for it. The film showed the attack so realistically that parts of it were later used in documentaries.

Around the same time, Toho's effects department was making Japan's first puppet film called Ramayana. Tsuburaya's next big projects were all war films. While making General Kato's Falcon Fighters (1944), Tsuburaya met Ishirō Honda for the first time. Honda would later direct many Godzilla films.

In February 1944, Masano and Tsuburaya's third son, Akira, was born. Akira was the first of their sons to be baptized. His mother had become a Catholic. Masano later convinced her husband to convert as well.

In late 1945, Tsuburaya made effects for Five Men from Tokyo. This was a comedy about men struggling after the war. During the Tokyo air raids in March 1945, Tsuburaya told his sons fairy tales in their bomb shelter to keep them calm.

The Birth of Godzilla and Beyond

Early Postwar Work (1946–1954)

Even though Toho was not hit by the Tokyo bombings, fewer films were made because of the Occupation of Japan. In 1946, Toho made only 18 films, and Tsuburaya worked on eight of them. Since his team had less work, Tsuburaya started trying out matte painting and optical printing.

Toho was facing problems because of labor disputes in the late 1940s. Tsuburaya had to sneak past police and U.S. tanks to get to work. These events led to the creation of Shintoho studio. Tsuburaya created effects for Shintoho's first film, A Thousand and One Nights with Toho (1947).

In March 1948, Tsuburaya was removed from Toho. This was because of his detailed miniatures in The War at Sea from Hawaii to Malaya. So, Toho closed its special effects division. Tsuburaya and his son Hajime started their own effects company. He then worked for other major film studios.

In 1949, Tsuburaya directed effects for five big Daiei Film movies. These included The Invisible Man Appears. This film was Japan's first big science fiction movie. It was also the country's first movie based on H. G. Wells' book The Invisible Man. Daiei wanted Tsuburaya's effects to be better than those in the American Invisible Man films. Tsuburaya was not happy with his work on the project. He gave up his dream of working for Daiei after The Invisible Man Appears was finished.

In 1950, Tsuburaya moved his company back to Toho. He slowly rebuilt the studio's Special Arts Department. He filmed all the title cards, trailers, and logos for Toho's films from 1950 to 1954.

In February 1952, Tsuburaya was allowed to work in public again. That same month, Ishirō Honda's film, The Skin of the South, was released. Tsuburaya directed the effects for the typhoon and landslide scenes. This was his first time working as an effects director for Honda. Tsuburaya, Honda, and producer Tomoyuki Tanaka worked together on The Man Who Came to Port later that year. This was the first time this trio, who created Godzilla, collaborated.

During World War II, Toho started researching 3D films. They created a 3D film process called "Tovision." This project was later brought back when the 3D film Bwana Devil (1952) became a hit in the United States. So, Toho made its first 3D film, The Sunday That Jumped Out (1953). Tsuburaya was the cameraman for this short film.

After this, Takeo Murata talked about making a tokusatsu film about a giant whale attacking Tokyo. Tsuburaya had thought of this idea the year before. He presented the idea to producer Iwao Mori. This project never happened, but parts of it were used in early ideas for Godzilla the next year.

Tsuburaya's next project was the war film Eagle of the Pacific (1953). This was his first big partnership with Ishirō Honda. The film used many effects scenes from The War at Sea from Hawaii to Malaya. So, Tsuburaya used a small team for the new effects. When it was released, the film earned a lot of money. The next year, he and Honda worked on another war film, Farewell Rabaul (1954). Its effects were even more advanced than in Eagle of the Pacific. Because of these successes, Tomoyuki Tanaka believed Tsuburaya should make more special effects films with Honda. Tsuburaya's next film would become Japan's first global hit.

International Recognition (1954–1959)

Producer Tomoyuki Tanaka decided to make a giant monster (or kaiju) film. He was inspired by The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953) and a real-life incident with a fishing boat. He thought monster films would be popular because of fears about nuclear power. Tsuburaya agreed to create the effects. So, the film, called Godzilla, was approved in April 1954. Ishirō Honda became the director. Tsuburaya thought about using stop motion for Godzilla. But he decided to use the "costume method" instead. This technique is now known as "suitmation."

Tsuburaya's special effects team filmed Godzilla in 71 days. They worked very hard, often from morning until the next morning. After Tsuburaya finished filming the effects, the movie was shown to the crew and cast. When it was released on November 3, Tsuburaya's effects were praised. The film became a huge hit. Godzilla made Toho the most successful effects company in the world. Tsuburaya won his first Japan Technical Award for his work.

Right after Godzilla, Tsuburaya started working on another science fiction film, The Invisible Avenger (1954). This film also had an invisible character. Tsuburaya used and improved the technology from his earlier film, The Invisible Man Appears. He told his team to show the character's invisibility in different ways, like using optical effects.

Because Godzilla was so successful, Toho quickly made a sequel, Godzilla Raids Again. Tsuburaya was officially called the special effects director for this film. Before, he was credited under "special technique." The film was shot in less than three months and opened in April 1955. A month later, Tsuburaya began directing effects for Half Human, his second monster film with Ishirō Honda. For this film, he created stop-motion animation and miniature avalanche scenes.

In April 1956, Godzilla became the first Japanese film to be widely shown in the United States. It was later released worldwide, making Tsuburaya famous internationally.

Tsuburaya's next big project was The Legend of the White Serpent. This was Toho's first special effects film fully made in color. Tsuburaya and his team spent a month training with color technology for this film. After this, Tsuburaya created the famous Toho logo. He also made the opening credits for most of the company's films.

Toho's next film for Tsuburaya was Rodan, the first monster film made in color. A lot of Rodan's budget was spent on Tsuburaya's effects. He used optical animation, matte paintings, and very detailed miniature sets. These sets were built to be destroyed or flown over by the monster Rodan. Rodan needed many model sets in different sizes. The film premiered in Japan in December 1956. When it was released in the United States the next year, it earned more money than any science fiction film before it.

Throne of Blood, a film by famous director Akira Kurosawa, was Tsuburaya's first film release of 1957. Kurosawa cut some of Tsuburaya's scenes. Tsuburaya then directed the effects for The Mysterians, a science fiction film by Ishirō Honda. It was the first color Cinemascope film by Honda and Tsuburaya. He won another Japan Technical Award for his widescreen effects in The Mysterians.

A new type of film for Toho started with Tsuburaya's first movie of 1958, The H-Man. This was the first in the "Transforming Human Series." He then directed effects for Honda's Varan the Unbelievable. This film was about a giant monster that wakes up in the mountains and appears in Tokyo Bay. Tsuburaya's last film released in 1958 was Kurosawa's The Hidden Fortress.

Tsuburaya started 1959 by directing special effects for a storm scene in Honda's Inao: Story of an Iron Arm. He also built the miniature for the main character's boat. Next, he worked on Monkey Sun, a remake of his 1940 film. He was inspired by soybean paste in his wife's soup. He created scenes with storm clouds and smoke from volcanoes. His effects in the film were called "comical and surreal." Tsuburaya then worked on Submarine I-57 Will Not Surrender, his first war film in six years. He built a model seabed for the submarine scenes.

Tsuburaya's next big film was The Three Treasures (1959). It was Toho's 1000th film. It was based on old Japanese legends. Tsuburaya and his team filmed big scenes like a battle between a character and an eight-headed dragon. They also filmed a volcano eruption. Tsuburaya used the "Toho Versatile Process" for the first time. He developed this for widescreen color films. The film earned a lot of money. He won another Japan Technical Award. Tsuburaya was happy with the film's success. But he was disappointed when he saw a newspaper photo of the dragon prop held up by wires. He felt it "broke children's dreams."

When the Space Race started in the late 1950s, Tsuburaya told Toho to make a film about a moon trip. He believed such a film would soon become real. So, his next film, Battle in Outer Space, was about astronauts fighting aliens on the moon. Tsuburaya paid tribute to another producer's film, Destination Moon (1950). Because his films were popular worldwide, a company filmed Tsuburaya directing the effects. He received a special award before the film's release.

From The Secret of the Telegian to Chūshingura (1960–1962)

In 1960, Tsuburaya's first project was a smaller science fiction film, The Secret of the Telegian. Next, Tsuburaya worked on a much bigger project, Storm Over the Pacific, the first color war film. The "Big Pool" was built at Toho Studios and used for the first time for this film. It was later used for almost every Godzilla film until it was taken down. Storm Over the Pacific was praised when it was released. Many of Tsuburaya's effects scenes were later used in another war film, Midway (1976). Later that year, he worked on The Human Vapor. He also oversaw the creation of a very detailed miniature of Osaka Castle and directed its destruction in The Story of Osaka Castle.

Next, Tsuburaya directed the effects for Mothra, another big monster film with Ishirō Honda. Tsuburaya created the giant divine moth monster, Mothra. Mothra became a famous Japanese movie icon, like Godzilla and Rodan. Even though the film had a huge budget for effects, Tsuburaya was not happy with some scenes. But he decided to keep them. The film opened on July 30, 1961. It became a huge hit and an "instant classic."

After directing dream scenes for The Youth and His Amulet (1961), Tsuburaya directed effects for the big special effects film The Last War. The Last War was a major hit in October 1961. Tsuburaya's effects were highly praised. He later called this film one of his "masterpieces." Producer Tomoyuki Tanaka gave Honda and Tsuburaya their biggest budget yet for their next science fiction film, Gorath. Even though Gorath has some of his best work, it did not do well at the box office when released in March 1962.

"My movie company came up with a very interesting script that combines King Kong and Godzilla, so I couldn't help working on this production instead of my new fantasy films. This script is very special to me; it struck a deep emotional chord because it was seeing King Kong back in 1933 that sparked my interest in the world of special visual effects."

After Gorath, Tsuburaya planned to work on other projects. But he put them aside to direct the special effects for Honda's King Kong vs. Godzilla. Early ideas for the script asked for the monster fights to be "funny." Tsuburaya liked this idea. He wanted to make the genre appeal to children. Much of the monster battle was filmed to be humorous. But some of the effects crew did not like it. They "couldn't believe" some of the things Tsuburaya asked them to do, like Kong and Godzilla throwing a giant rock back and forth. Tsuburaya let the actors playing Godzilla and King Kong create their own moves. Tsuburaya filmed scenes of a giant octopus attacking a village. He even ate some of the octopus props for dinner! When it was released in August 1962, King Kong vs. Godzilla became the second-highest-earning Japanese film ever. It was watched by 11.2 million people. This made it the most-watched film in the Godzilla series.

Tsuburaya's final film of 1962 was Chūshingura: Hana no Maki, Yuki no Maki. For this film, he and his team made special stages and optical effects. This film was also made to celebrate Toho's 30th anniversary.

Creating His Own Company

Birth of a Company and Career Expansion (1963–1965)

The first film in 1963 with Tsuburaya's effects was Attack Squadron!. This war film featured many miniature Japanese and American aircraft. The only new miniature battleship built for the film was the Yamato. It was a huge motorized model, 17.5 meters (57.5 feet) long.

After visiting Hollywood to see special effects, Tsuburaya started his own company. It was called Tsuburaya Special Effects Productions (later just Tsuburaya Productions). This happened on April 12, 1963. His family ran the company. Tsuburaya was the director, his wife Masano was on the board, and his second son Noboru was the accountant. His oldest son Hajime also joined. Tsuburaya hired Koichi Takano for his company's first big special effects film, Alone Across the Pacific (1963). Tsuburaya worked for his new company and Toho at the same time.

Tsuburaya's next film was The Siege of Fort Bismarck. This was a "lighthearted World War I adventure." His team made new models for the film. These included large miniatures and full-size copies of early airplanes. Tsuburaya enjoyed working on this film.

After finishing The Siege of Fort Bismarck in April 1963, he started working on Matango. This was another film with Ishirō Honda. It was the last in the Transforming Human Series. For this film, actors could physically interact with the monsters. Tsuburaya made Toho buy a special "Optical Printer 1900 Series." This helped with the film's effects. The film did not do well at the box office.

Tsuburaya soon started filming miniatures and creating optical animation for The Lost World of Sinbad. This film had an acclaimed chase scene between a wizard and a witch. This scene earned Tsuburaya another Japan Technical Award.

Tsuburaya immediately started working on another Honda-directed science fiction movie, Atragon (1963). This film was about an ancient undersea civilization invading the surface world. Toho wanted to release the film quickly. So, Tsuburaya had only about two months to film the effects. He split his special effects team into two units to finish the work faster. Four miniatures were built for the Gotengo battleship. The largest was a radio-controlled model, 4.5 meters (15 feet) long. Even though it was made quickly, the film is still considered "one of the cornerstones of Japanese cinema."

This was a very busy time for Tsuburaya. He was finishing effects for Whirlwind and Atragon at the same time. He often fell asleep in his chair during filming because of lack of sleep.

The third Godzilla film, Mothra vs. Godzilla (1964), was Tsuburaya's next movie. Many people think it is Tsuburaya's best monster film. It was made to celebrate 10 years of Toho's monster films. It shows a battle between Godzilla and Mothra. He used his optical printer to fix problems in the shots and to create Godzilla's atomic breath. Tsuburaya filmed some scenes of Nagoya Castle for the part where Godzilla destroyed it. The first model of the castle was too strong. So, Tsuburaya had to reshoot the scene with a new model that would crumble more easily.

In spring 1964, Tsuburaya was visited by Ishirō Honda in Hawaii. Tsuburaya was filming a dogfight and plane crash scene for Frank Sinatra's movie None but the Brave (1965). This was Sinatra's only film as a director. It was the first Japanese-American co-production. Tsuburaya told Honda he was planning his first TV series, Unbalance. But he was having trouble finding a main actor. Honda convinced Kenji Sahara to play the team leader for the show. This show later became Ultra Q (1966).

In January 1964, Tsuburaya ordered a special optical printer from New York. Only one other studio in the world, Disney, owned one. It cost a lot of money. Tsuburaya wanted it for Tsuburaya Productions because it was a very useful tool. He used this technology on Ultra Q, his company's first TV series. Filming for Ultra Q began in September 1964. The series aired from January to July 1966. It was about a trio who investigated strange things like monsters. When it aired, 30% of Japanese homes with TVs watched the show. This made Eiji Tsuburaya a household name. The media started calling him the "God of Tokusatsu."

After directing effects for Honda's monster film Dogora (1964), he worked on another Honda-directed monster film, Ghidorah, the Three-Headed Monster. This made 1964 the only year two Godzilla films were released. This film had a dragon monster, King Ghidorah, who fought Godzilla, Rodan, and Mothra. Screenwriter Shinichi Sekizawa suggested making the Ghidorah suit from light material for more movement. Tsuburaya and Toho decided to make the monsters more human-like. During filming, a part of the water tank was accidentally shown. Tsuburaya hid this mistake by adding trees in the area. Released in December 1964, Ghidorah was a huge hit. King Ghidorah became a frequent enemy in the Godzilla series.

Tsuburaya's next film, Frankenstein vs. Baragon, had a long history. It started as an American idea for King Kong fighting Frankenstein. This idea came to Toho, but they made King Kong fight Godzilla instead. Later, a writer suggested Frankenstein fighting Godzilla. This idea was changed to Frankenstein fighting a new monster called Baragon. Tsuburaya was excited about this film. The monsters were smaller than usual, so his team could build bigger model sets. Also, an actor in makeup played Frankenstein, not a stuntman in a suit. The film had very large and detailed model sets. Tsuburaya also made a scene showing the atomic bomb falling on Hiroshima.

After the film was finished for its Japanese release in August 1965, the American co-producer asked for a new ending. He wanted Frankenstein to fight a giant octopus. Tsuburaya and Honda filmed this new ending. But it was not used in the final movie.

After directing effects for the war film Retreat From Kiska (1965), Tsuburaya began work on Honda's Invasion of Astro-Monster (1965). This was the sixth Godzilla film. It was about two astronauts who land on a planet where aliens ask for help fighting King Ghidorah. The aliens then try to use Godzilla, Rodan, and Ghidorah to conquer Earth. This film famously features Godzilla's "Shie" victory dance. An actor suggested it to Tsuburaya, who liked making monsters more human-like and comical. Tsuburaya won awards for his work on both Kiska and Invasion of Astro-Monster.

Ultraman and Beyond (1966–1967)

In 1966, Tsuburaya's company aired the first Ultra series for television, Ultra Q, starting in January. This was followed by the very popular Ultraman in July. They also premiered a comedy-monster series, Monster Booska, in November. Ultraman became the first live-action Japanese TV series to be shown worldwide. It started the Ultra series, which is still going strong today.

Final Works and Last Years (1968–1970)

Toward the end of his life, Tsuburaya planned a film called Japan Airplane Guy. But it was never made. Tsuburaya was told to work less because his health was getting worse. But he kept taking on more projects. He divided his time between Tsuburaya Productions and directing special effects for two Toho films, Latitude Zero and Battle of the Japan Sea. He was also hired to oversee a special exhibit at Expo '70 in Osaka. On January 25, 1970, he passed away from a heart attack caused by asthma. He was sleeping with his wife at their home. Five days later, on January 30, 1970, Emperor Hirohito gave him the "Order of the Sacred Treasure." His funeral was held at Toho Studios. He was later buried at Catholic Cemetery in Fuchū, Tokyo, Japan.

Filmmaking

Filming and Editing

According to special effects cameraman Sadamasa Arikawa, Tsuburaya also edited his own film work. Tsuburaya's assistant director said that he remembered where all his filmed cuts were stored. A writer named Keiko Suzuki said Tsuburaya had his own editing plan. He often filmed scenes without a script. So, for example, scenes were changed to become "Battle 1" and "Aerial Battle 2."

Legacy

Tsuburaya Productions called Tsuburaya the "Father of Tokusatsu" because of his "amazing balance of technique and entertainment." Doug Bolton from The Independent wrote that even "people not familiar with Japanese science fiction will easily recognise the legacy of Tsuburaya's work." The Tokusatsu Network said that Tsuburaya was "possibly the most influential figure in the Japanese film industry." They said his work "lives on to this day through his creations." He has even been compared to Walt Disney.

Posthumous Works

Tsuburaya had planned to work on Space Amoeba (1970). But he passed away shortly after filming began. The film was finished in his honor. However, Toho executives did not give him a dedication in its opening credits.

Many works have been created based on Tsuburaya's ideas that were never filmed. Tsuburaya wrote a script for a project called Princess Kaguya before he died. His son Hajime tried to make Princess Kaguya into a film for Tsuburaya Productions' 10th anniversary. Tsuburaya had wanted to make a film that children around the world would enjoy. But Hajime passed away before production could begin. In 1987, producer Tomoyuki Tanaka made Eiji Tsuburaya's dream into a live-action movie called Princess from the Moon. It featured effects directed by Tsuburaya's student, Teruyoshi Nakano.

In 2020, filmmaker Minoru Kawasaki made a film based on Tsuburaya's unmade film about a giant octopus.

Portrayals

Many actors have played Tsuburaya in TV shows. In the 1989 TV drama The Men Who Made Ultraman, a famous Toho actor was first chosen to play Tsuburaya. But he declined, saying he didn't look enough like Tsuburaya. So, actor Kō Nishimura was cast instead. In 1993, filmmaker Seijun Suzuki played Tsuburaya in the TV drama I Loved Ultraseven. For The Pair of Ultraman (2022), he was played by Toshiki Ayada.

Tributes

To honor his 114th birthday, Google made an animated doodle of his special effects skills on July 7, 2015. On January 11, 2019, the Eiji Tsuburaya Museum opened in his hometown of Sukagawa. It is a tribute to his life and work in film and television.

Selected Filmography

Films

- A Page of Madness (1926)

- Princess Kaguya (1935)

- The New Land (1937)

- The Abe Clan (1938)

- The Burning Sky (1940)

- The War at Sea from Hawaii to Malaya (1942)

- General Kato's Falcon Fighters (1944)

- A Thousand and One Nights with Toho (1947)

- Lady from Hell (1949)

- The Invisible Man Appears (1949)

- Escape at Dawn (1950)

- The Skin of the South (1952)

- The Man Who Came to Port (1952)

- Anatahan (1953)

- Eagle of the Pacific (1953)

- Farewell Rabaul (1954)

- Godzilla (1954)

- The Invisible Avenger (1954)

- Godzilla Raids Again (1955)

- Half Human (1955)

- The Legend of the White Serpent (1956)

- Rodan (1956)

- Throne of Blood (1957)

- The Mysterians (1957)

- The H-Man (1958)

- Varan (1958)

- The Hidden Fortress (1958)

- Monkey Sun (1959)

- Submarine I-57 Will Not Surrender (1959)

- The Three Treasures (1959)

- Battle in Outer Space (1959)

- The Secret of the Telegian (1960)

- Storm Over the Pacific (1960)

- The Human Vapor (1960)

- The Story of Osaka Castle (1961)

- Mothra (1961)

- The Last War (1961)

- Gorath (1962)

- King Kong vs. Godzilla (1962)

- Chūshingura: Hana no Maki, Yuki no Maki (1962)

- Attack Squadron! (1963)

- Matango (1963)

- The Lost World of Sinbad (1963)

- Atragon (1963)

- Whirlwind (1964)

- Mothra vs. Godzilla (1964)

- Dogora (1964)

- Ghidorah, the Three-Headed Monster (1964)

- None but the Brave (1965)

- Frankenstein vs. Baragon (1965)

- Invasion of Astro-Monster (1965)

- The War of the Gargantuas (1966)

- Ebirah, Horror of the Deep (1966)

- King Kong Escapes (1967)

- Son of Godzilla (1967)

- Destroy All Monsters (1968)

- Latitude Zero (1969)

- Battle of the Japan Sea (1969)

- All Monsters Attack (1969)

Television

- Ultra Q (1966)

- Modern Leaders [episode, "The Father of Ultra Q"] (1966)

- Ultraman (1966-1967)

- Monster Booska (1966-1967)

- Mighty Jack (1968)

- Fight! Mighty Jack (1968)

Awards and Honors

| Year | Award | Category | Nominated work | Result | Ref(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1940 | Japan Motion Picture Cinematographers Association | Special Technology Award | The Burning Sky | Won | |

| 1942 | Technical Research Award | The War at Sea from Hawaii to Malaya |

|||

| 1954 | 8th Japan Technical Awards | Special Skill | Godzilla | ||

| 1957 | 11th Japan Technical Awards | The Mysterians | |||

| 1959 | 13th Japan Technical Awards | The Three Treasures | |||

| 4th Movie Day | Special Award of Merit | N/A | |||

| 1963 | 17th Japan Technical Awards | Special Skill | The Lost World of Sinbad | ||

| 1965 | 19th Japan Technical Awards | Retreat From Kiska | |||

| 1966 | 20th Japan Technical Awards | Invasion of Astro-Monster | |||

| 1970 | N/A | 4th Class Medal of Order of the Sacred Treasure |

N/A | ||

| Japanese Society of Cinematographers | Honorary Chairman Award |

See also

In Spanish: Eiji Tsuburaya para niños

In Spanish: Eiji Tsuburaya para niños

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |