French expedition to Ireland (1796) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Expédition d'Irlande |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of the First Coalition | |||||||

End of the Irish Invasion ; — or – the Destruction of the French Armada, James Gillray |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 13 warships | 15,000–20,000 44 warships |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Light, if any | 2,230 killed or drowned, 1,000 captured, 12 warships captured or wrecked |

||||||

The French expedition to Ireland was a large-scale plan by France to help Irish rebels fight against Great Britain. It was known in French as the Expédition d'Irlande. The goal was to land a big army in Ireland during the winter of 1796–1797. This army would then join with the Society of United Irishmen, a group of Irish people who wanted Ireland to be free.

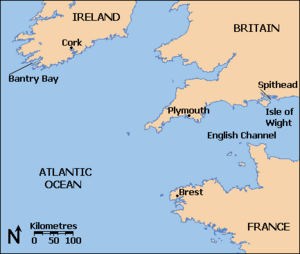

The French hoped this would be a major blow to British power. They also thought it could be the first step towards invading Britain itself. About 15,000 French soldiers were gathered at Brest under General Lazare Hoche. They planned to land at Bantry Bay in December.

However, the operation happened during one of the stormiest winters ever. The French fleet was not ready for such bad weather. British ships saw them leave and warned the British navy. The French fleet also got confused orders and scattered. One ship sank, and others were spread out.

Most of the French fleet reached Bantry Bay in late December. But their commanders were blown far off course. Without them, the fleet didn't know what to do. Landing troops was impossible due to the terrible weather. Within a week, the fleet broke up. Small groups of ships tried to return to Brest through storms, fog, and British patrols.

The British navy couldn't do much to stop the French. Only a few British ships captured isolated French vessels. Captain Edward Pellew was the only one to cause major damage. He forced the French ship Droits de l'Homme ashore, causing over 1,000 deaths. In total, France lost 12 ships and thousands of soldiers and sailors. Not a single French soldier landed in Ireland, except as prisoners of war.

Contents

Why Did France Invade Ireland?

Ireland's Desire for Freedom

After the French Revolution started in 1789, many countries became interested in republicanism. This idea of a country ruled by its people, not a king, spread to Ireland. At that time, Ireland was ruled by Great Britain.

Irish people had wanted freedom for centuries. But the French example, along with unfair laws called the Penal Laws, made things worse. These laws treated the Catholic majority and many Presbyterians unfairly.

This led to the creation of the Society of United Irishmen. This group wanted to create an Irish Republic. At first, they were peaceful. But when their group was made illegal in 1793, they became a secret society. They decided their only hope was an armed revolt.

Irish Rebels Seek French Help

The United Irishmen secretly began to organize and arm themselves. They looked for help from other countries. Two of their leaders, Lord Edward FitzGerald and Arthur O'Connor, met with French General Lazare Hoche.

A lawyer named Theobald Wolfe Tone also went to Paris. He asked the French government, called the French Directory, for help in person. During this time, the British government tried to calm things down. They removed some of the unfair Penal Laws.

France's Plan to Weaken Britain

The First French Republic had long wanted to invade the British Isles. But other wars and problems with their navy stopped them. The French Navy had lost many officers during the Revolution. They also suffered several defeats in battle.

In 1795, France made peace on several fronts. The new French Directory decided that Britain was their biggest enemy. They wanted to defeat Britain by invading.

The French Directory was very interested in Tone's request. They knew that attacking Ireland would hit Britain where it was weakest. Support for the British government was low in Ireland. The United Irishmen even claimed they could raise an army of 250,000 people to join the French. A free Ireland would also be a big win for France's ideas.

Most importantly, a large French army in Ireland could be a perfect starting point for invading Britain itself.

Getting Ready for the Invasion

Gathering Troops and Ships

With other wars ending, France had many soldiers available. General Hoche was chosen to lead the operation. He was a successful military commander. He was given a large group of experienced soldiers and the entire French Atlantic Fleet. They were based at Brest.

The exact number of soldiers for the invasion is not clear. The French Directory thought 25,000 men were needed. The Irish delegates said 15,000 would be enough. Estimates of the soldiers who actually went range from 13,500 to 20,000.

Delays and Problems

By August, the plan was already behind schedule. There were not enough supplies or money at the Brest shipyards. Soldiers also deserted in large numbers.

A practice trip for a smaller invasion fleet failed completely. The small ships couldn't handle the open sea. This plan was dropped. The good soldiers from that unit joined the Ireland expedition.

Ships from the French Mediterranean Fleet were also delayed. Seven ships had to hide from the British navy. They only arrived in Brest on December 8. Another group of ships arrived even later, after the main expedition had already left.

Throughout late 1796, the expedition kept getting delayed. General Hoche blamed the naval commander, Vice-Admiral Louis Thomas Villaret de Joyeuse. He said the admiral was more interested in invading India. In October, a new admiral, Justin Bonaventure Morard de Galles, took over. The India plans were cancelled. Hoche was put in charge of discipline for the fleet.

The Fleet is Ready

By the second week of December, the fleet was finally ready. It had 17 large warships (ships of the line), 13 smaller warships (frigates), and 14 other vessels. Some old frigates had their cannons removed to carry more cargo.

Each large warship carried 600 soldiers. Frigates carried 250. Transports carried about 400. The fleet also carried cavalry, artillery, and many military supplies. These supplies were meant to arm the thousands of Irish volunteers they expected.

Hoche was still not happy. He told the Directory on December 8 that he would rather lead his men anywhere else. Admiral Morard de Galles agreed. He said his sailors were so new to sea that they should avoid fighting the enemy if possible.

Leaving France: A Confused Start

British Spies and French Plans

Despite their worries, the fleet left Brest on December 15, 1796. This was one day before a message from the Directory arrived, calling off the whole operation!

Admiral de Galles knew the British were watching Brest. Their frigates were always nearby, blocking the port. To hide his plans, he first anchored in Camaret Bay. He ordered his ships to go through the Raz de Sein. This was a dangerous, narrow channel with rocks and strong waves. But it would also hide the size and direction of the French fleet from the British.

Pellew's Warning

The main British blockade fleet was not near Brest on December 15. Most of it had gone to British ports to avoid winter storms. The remaining British ships had moved far out into the Atlantic to avoid being pushed onto the French coast by a storm.

The only British ships near Brest were a group of frigates. They were led by Captain Edward Pellew in HMS Indefatigable. Pellew had seen the French getting ready on December 11. He immediately sent two of his frigates to warn the British navy. He stayed near Brest with the rest of his ships.

Pellew saw the main French fleet at 3:30 PM on December 15. He brought his frigates closer to see how big it was. At 3:30 PM on December 16, the French sailed from the Bay. Pellew watched closely and sent another frigate to help find the main British fleet.

Chaos in the Dark

Admiral Morard de Galles spent most of December 16 getting ready to go through the Raz de Sein. He placed temporary lightships to mark dangers. He also gave instructions for using signal rockets. But the fleet was so slow that it got dark before they were ready.

At about 4:00 PM, he gave up on the Raz de Sein plan. He signaled for the fleet to leave through the main channel. He led the way in his flagship, the frigate Fraternité. It was so dark that most ships didn't see the signal. Fraternité and another ship tried to tell them with rocket signals.

These signals were confusing. Many ships didn't understand and sailed for the Raz de Sein instead of the main channel. Captain Pellew made things worse. He sailed ahead of the French fleet, flashing blue lights and firing rockets. This confused the French captains even more about where they were.

A Fleet Scattered

When dawn broke on December 17, most of the French fleet was scattered. The largest group was led by Vice-Admiral François Joseph Bouvet. He had come through the Raz de Sein with nine warships, six frigates, and one transport ship. The other ships, including Fraternité (which carried General Hoche), were alone or in small groups.

The captains had to open their secret orders to find out their destination. One ship was lost: the 74-gun Séduisant hit a rock during the night and sank. About 680 people died. This ship also fired many rockets and signal guns, which only added to the confusion. Pellew, unable to fight such a large French force, sailed to Falmouth to send his report to the British Admiralty.

The Stormy Voyage to Ireland

Bouvet Reaches Bantry Bay

By December 19, Admiral Bouvet had gathered 33 ships. He set a course for Mizen Head in southern Ireland. This was the meeting point where his secret orders told him to wait five days. One of the missing ships was Fraternité, carrying the commanders.

Even though their commanders were missing, the French fleet continued towards Bantry Bay. They sailed through strong winds and thick fog. This delayed their arrival until December 21. While Bouvet sailed for Ireland, Fraternité searched for the fleet.

Admiral de Galles on Fraternité accidentally passed Bouvet's fleet in the fog. On December 21, he saw a British frigate right in front of him. Fraternité was chased far into the Atlantic before escaping. On the way back, de Galles faced strong winds. It took him eight days to get back to Mizen Head.

British Fleet Delays

The British response was slow. Captain Pellew's warning didn't reach Admiral Colpoys until December 19. Colpoys chased a French squadron, but they escaped in a gale. Colpoys' ships were damaged and had to go back for repairs.

The main British Channel Fleet, led by Lord Bridport, also struggled. News of the French leaving Brest didn't reach Plymouth until December 20. Many of Bridport's ships were not ready. It took days to get enough ships manned.

When Bridport finally tried to leave on December 25, his fleet immediately ran into trouble. Several large ships crashed into each other in strong winds. All five damaged ships needed major repairs. This delayed Bridport's departure even more. When he finally reached the departure point, the wind was blowing against him. His remaining eight ships were stuck until January 3.

Stuck in Bantry Bay

Without Admiral Morard de Galles and General Hoche, Admiral Bouvet and General Emmanuel de Grouchy gave orders on December 21. They told the fleet to anchor to prepare for landings the next day. Local boat pilots, thinking the fleet was British, rowed out to the ships. They were captured and forced to guide the French to the best landing spots.

During the night of December 21, the weather suddenly got much worse. Atlantic gales brought blizzards that hid the shoreline. The fleet had to anchor or risk being destroyed. They stayed in the Bay for four days in the coldest winter since 1708. The French sailors were new to sea and had no winter clothes. They couldn't operate their ships.

On shore, local Irish forces gathered, ready to fight if the French landed. On December 24, the wind calmed a little. The French officers decided to try landing despite the weather. They found a nearby creek as the safest spot. They planned to land at dawn on December 25.

But during the night, the weather got worse again. By morning, the waves were so violent they crashed over the ships. Anchors broke, and many ships were blown out of the Bay into the Atlantic. They couldn't return against the wind. In the storm, the largest warship, the Indomptable, crashed into the frigate Résolue. Both were badly damaged.

The Expedition Collapses

For four more days, Bouvet's ships were hit by strong winds. None could get close to shore without risking being destroyed on the rocky coast. Many ships lost their anchors and were forced to scatter into the Atlantic. Others were destroyed.

An American ship saw a French frigate, Impatiente, sinking on December 29. Only seven men survived from its 550 crew and passengers. The American captain also saw another French ship, Scévola, sinking. Its crew was being rescued before it was burned.

Admiral Bouvet's ship, Immortalité, was blown offshore during the storm. When the wind died down on December 29, he decided to give up. He ordered his remaining ships to sail back to Brest. Some ships didn't get the message and continued to a second meeting point. But they were few and scattered. No landing was possible in the continuing storms. With food running low, these ships also turned back to Brest.

As their fleet sailed home, Morard de Galles and Hoche finally arrived in Bantry Bay on December 30. They found that the fleet was gone. With their own food almost gone, Fraternité and Révolution also had to return to France.

The British response was still not good enough. Admiral Colpoys arrived back at Spithead on December 31 with only six ships. Only a few British ships based at Cork managed to interfere with the French. They captured a few French transport ships.

The Difficult Retreat Home

French Ships Return to Brest

The first French ships to return to Brest arrived on January 1. These included Bouvet's flagship Immortalité and several other large warships. They had avoided British ships and made good speed in calm weather.

In the following days, the French ships that had gathered off the River Shannon slowly returned. All were badly damaged by the rough seas and strong winds. Several ships did not make it back to France at all. The frigate Surveillante was sunk in Bantry Bay on January 2. Many people on board, including 600 cavalrymen, were rescued by other French boats. Others swam ashore and became prisoners of war.

On January 5, the British ship HMS Polyphemus captured the French frigate Tartu. The Royal Navy later used this ship themselves. Polyphemus also captured another transport ship, but it was too stormy to take it. The British captain thought it likely sank. This might have been the transport Fille-Unique, which sank on January 6.

On January 7, British frigates captured another French transport ship. The next day, two British frigates saw the damaged Révolution and Fraternité (carrying Hoche and de Galles). The British frigates retreated, leading the French ships away from their route back to France.

When the British frigates reappeared the next morning, they were scouting for Lord Bridport's fleet. Bridport's fleet had finally left port. Révolution and Fraternité escaped in a fog and sailed directly to France, arriving on January 13.

Most of the remaining French ships reached Brest on January 11 and 13. Losses continued as the French neared Brest. The disarmed Suffren was recaptured by a British ship and burned on January 8. Atalante was captured by HMS Phoebe on January 10. Another French supply ship was captured on January 12.

The Last Battle: Droits de l'Homme

By January 13, all French ships were accounted for except two. One was a small brig that ended up in the Canary Islands. The other was the 74-gun Droits de l'Homme. This ship had been with the fleet in Bantry Bay and then went to the Shannon. But it got separated.

With food running low and no way to land, Captain Jean-Baptiste Raymond de Lacrosse decided to return to France alone. Progress was slow because Droits de l'Homme was overloaded with 1,300 men, including 800 soldiers. It was further delayed when it captured a small British privateer ship.

As a result, Lacrosse only reached Ushant by January 13. There, he met the same fog that had helped Révolution and Fraternité escape.

At 1:00 PM, two ships appeared from the fog. Lacrosse turned away to avoid a fight. But the ships kept coming. They were the British frigates Indefatigable (Captain Sir Edward Pellew) and Amazon (Captain Robert Carthew Reynolds). They had resupplied and returned to their station near Brest.

As Droits de l'Homme sailed southwest, the winds grew stronger. The sea became rough. Lacrosse couldn't open his lower gunports without risking flooding. His topmasts broke, making his ship less stable. Pellew saw his enemy's problems. He moved closer and began a heavy attack.

The battle continued all night. The faster British ships would pull away to repair damage, then return to attack the French ship.

At 4:20 AM on January 14, lookouts on all three ships saw waves breaking to the east. Desperate to escape the strong waves, Indefatigable turned north and Amazon turned south. But the damaged Droits de l'Homme couldn't turn. It crashed onto a sandbar near the town of Plozévet. The waves rolled it onto its side.

Amazon also crashed, but in a more protected spot. It stayed upright. The only ship that survived was Indefatigable. It managed to get around the rocks and reach open water.

The French officers on Droits de l'Homme couldn't launch their boats. The waves destroyed every attempt, drowning hundreds of men. Losses grew as the storm continued. The ship's stern broke open, flooding the inside. On January 15, some prisoners from the captured British ship reached shore in a small boat. But other attempts failed. It wasn't until January 17 that the sea calmed enough for a small French naval ship to approach the wreck and rescue the remaining 290 survivors.

What Happened Next?

Failure and Future Attempts

The French attempt to invade Ireland was a complete failure. No French soldier successfully landed in Ireland, except as prisoners. Twelve ships were lost, and over two thousand soldiers and sailors drowned.

The invasion was called off. General Hoche and his remaining men returned to the army in Germany. Hoche died nine months later from natural causes.

The French Navy was criticized for not landing the troops. But they were also praised for reaching Ireland and returning without meeting the main British fleet. This encouraged them to try again. They made a small landing in Wales in February 1797 (Battle of Fishguard). They also tried a second invasion of Ireland in mid-1798.

British Response and Irish Rebellion

In Britain, the Royal Navy was heavily criticized. Both fleets sent to stop the invasion failed. The only losses for the French came from the small Cork squadron or Pellew's independent frigates.

In Ireland, the failure of the French expedition was very disappointing. Wolfe Tone, who was on board a French ship, felt he could have almost touched both sides of Bantry Bay. The planned uprising was delayed. Tone continued to seek support in Europe. He gathered a fleet in the Netherlands for another invasion attempt, but it was destroyed at the Battle of Camperdown.

In May 1798, the British arrested the leaders of the United Irishmen in Ireland. This caused the Irish Rebellion. By the time the French managed to send a small force to Ireland in August, the rebellion was almost over. The small French army surrendered in September at the Battle of Ballinamuck. Another invasion attempt the next month also failed. The French ships were stopped and defeated at the Battle of Tory Island.

Wolfe Tone was captured and died. His death, along with military defeats and harsh actions against the Irish rebels, ended both the Society of United Irishmen and French invasion plans for Ireland.

See also