Félix Houphouët-Boigny facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Félix Houphouët-Boigny

|

|

|---|---|

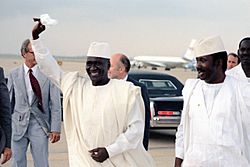

Houphouët-Boigny in 1962

|

|

| 1st President of Côte d'Ivoire | |

| In office 3 November 1960 – 7 December 1993 |

|

| Preceded by | None (position established) |

| Succeeded by | Henri Konan Bédié |

| 1st Prime Minister of Côte d'Ivoire | |

| In office 7 August 1960 – 27 November 1970 |

|

| Preceded by | None (position established) |

| Succeeded by | Position abolished Alassane Ouattara (1990) |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Dia Houphouët

18 October 1905 Yamoussoukro, French West Africa |

| Died | 7 December 1993 (aged 88) Yamoussoukro, Ivory Coast |

| Nationality | Ivorian |

| Political party | Democratic Party |

| Spouses | Kady Racine Sow (1930–1952; divorced) Marie-Thérèse Houphouët-Boigny (1962–1993; his death) |

Félix Houphouët-Boigny (born October 18, 1905 – died December 7, 1993) was the very first president of Ivory Coast. People often called him Papa Houphouët or Le Vieux ("The Old One"). He led the country from 1960 until he passed away in 1993.

Before becoming president, he was a tribal chief. He also worked as a medical helper, a leader for workers' groups, and a farmer. Later, he was elected to the French Parliament. He held several important jobs in the French government before Ivory Coast became independent in 1960. He played a big part in politics and in helping African countries gain freedom from colonial rule.

Under Houphouët-Boigny's leadership, Ivory Coast became very successful economically. This success was rare in West Africa and was called the "Ivorian miracle." It happened because of good planning, keeping strong connections with Western countries (especially France), and growing the country's coffee and cocoa industries. However, relying too much on farming caused problems in 1980 when coffee and cocoa prices dropped sharply.

He kept a close relationship with France, a policy known as Françafrique. He was also known as the "Sage of Africa" or the "Grand Old Man of Africa." Houphouët-Boigny moved the country's capital from Abidjan to his hometown of Yamoussoukro. There, he built the world's largest church, the Basilica of Our Lady of Peace of Yamoussoukro. When he died, he was the longest-serving leader in Africa. In 1989, UNESCO created the Félix Houphouët-Boigny Peace Prize to honor people who work for peace. After his death, Ivory Coast faced many challenges, including a civil war that started in 2002.

Contents

Early Life and Career

Birth and Education

Félix Houphouët-Boigny was likely born on October 18, 1905, in Yamoussoukro. He came from a family of traditional chiefs of the Baoulé people. Some unofficial stories say he might have been born a few years earlier. He was born into the Akouès tribe, which followed traditional African beliefs. His first name, Dia, meant "prophet" or "magician."

His great-aunt, Queen Yamousso, and the village chief, Kouassi N'Go, were important figures in his family. When N'Go was killed in 1910, Dia was chosen to become the next chief. Because he was so young, his stepfather, Gbro Diby, ruled as a temporary leader until Dia was old enough.

The French rulers wanted tribal leaders to go to school. So, Houphouët went to a military school in Bonzi, near his village, to prepare for his future role. In 1915, he moved to a secondary school in Bingerville. That same year, he became a Christian and chose the name Félix. He thought Christianity was a modern religion and could help stop the spread of Islam.

He was a top student and went to the École William Ponty in 1919, where he earned a teaching degree. In 1921, he studied at the French West Africa School of Medicine in French Senegal. He finished first in his class in 1925 and became a medical assistant. Since he didn't complete all his medical studies, he was called a médecin africain, which was a lower-paid doctor.

Medical Work and Activism

On October 26, 1925, Houphouët started working as a doctor's helper in a hospital in Abidjan. He tried to start a group for local medical workers, but the French rulers didn't like it. They saw it as a trade union and moved him to a smaller hospital in Guiglo in 1927.

However, he showed great skill and was promoted in 1929 to a job in Abengourou. This job was usually only for Europeans. In Abengourou, Houphouët saw how badly the French treated local cocoa farmers. In 1932, he decided to act. He led a movement of farmers against the powerful white landowners. He even wrote an article in an Ivorian newspaper called "They have stolen too much from us." He used a fake name for the article.

The next year, his tribe asked him to become the village chief. But he preferred his medical career and let his younger brother, Augustin, take the role. He moved closer to his village, working in Dimbokro and then Toumodi. In 1938, his boss told him to choose between his medical job and local politics. His brother died in 1939, so Houphouët became a chef de canton (a local leader appointed by the French to collect taxes). He ended his medical career the next year.

Leader of Farmers

As chef de canton, Houphouët was in charge of 36 villages in the Akouè area. He also managed his family's large plantation, growing rubber, cocoa, and coffee. He became one of the richest farmers in Africa.

In 1944, he started the African Agricultural Union (SAA) with the help of the French rulers. This union brought together African farmers who were unhappy with their working conditions. It aimed to protect their interests against European farmers. The SAA fought against unfair colonial practices and demanded better pay and an end to forced labor. The union quickly gained support from almost 20,000 plantation workers. Its success bothered the European colonists, who even tried to take legal action against Houphouët. However, he had friends in the French government who helped drop the charges.

In August 1945, Houphouët entered politics. He created a group called the African Bloc, which won many seats in the Abidjan city council elections. In October 1945, he became involved in national politics. The French government decided to have representatives from its colonies in the French Parliament. Houphouët ran for the seat representing the local population and won easily. At this point, he added "Boigny" to his name, which means "irresistible force" in Baoulé. This symbolized his strong leadership.

French Political Career

Member of Parliament

When Houphouët-Boigny took his seat in the National Assembly in Paris, he joined a small group of Communist sympathizers. He became part of the committee for overseas territories. During this time, he worked to help African farmers. He proposed a law to stop forced labor, which was a very unpopular part of French rule. This law, called Loi Houphouët-Boigny, was passed in April 1946. This made him very popular beyond Ivory Coast. He also worked to improve health care in African territories. Houphouët-Boigny supported the idea of a "French Union," which would connect French territories.

In 1946, new elections were held. Houphouët-Boigny started the Democratic Party of Côte d'Ivoire (PDCI). This party was very successful and he easily won the elections again. He was helped by a new governor who was more supportive of African rights.

He continued to work in the Assembly, proposing reforms to better represent African people. He also called for local assemblies in Africa so that Africans could learn to govern themselves.

Starting the RDA and Communist Alliance

African representatives felt that the French government was going back on its promises. They decided to form their own political group, separate from French parties. Houphouët-Boigny suggested this, and they formed the African Democratic Rally (RDA) in October 1946. Its goal was to free "Africa from colonial rule." Houphouët-Boigny became its first president. The PDCI became the Ivory Coast branch of the RDA.

The African representatives were too few to form their own group in Parliament. So, the RDA joined the French Communist Party (PCF). This was because the Communists were the only ones openly against colonialism. Houphouët-Boigny said this alliance helped them achieve things, like ending forced labor. He defended himself against being called a Communist, saying, "Can I, Houphouet, a traditional leader, doctor, big landowner, Catholic, can we say that I am a communist?"

As the Cold War began, the alliance with the Communists became a problem for the RDA. The French rulers became very hostile towards Houphouët-Boigny and his party, calling him a "Stalinist." His party faced more and more repression in Ivory Coast. Many party members were arrested, beaten, or lost their jobs. One important leader, Senator Biaka Boda, was found dead. Houphouët-Boigny feared for his life.

Tensions were very high in 1950. After some anti-colonial violence, almost all the PDCI leaders were arrested. Houphouët-Boigny managed to escape just before the police arrived. Riots broke out in Ivory Coast, and many Africans were killed or wounded. To calm things down, the French government asked Houphouët-Boigny to break ties with the Communists. In October 1950, he agreed. He later said he worked with the Communists because it was the only way for his voice to be heard.

Becoming a Government Minister

In the 1951 elections, Houphouët-Boigny still won a seat. In 1956, his party won a huge number of votes. From then on, his past connection with Communism was forgotten, and he was seen as a moderate leader.

On February 1, 1956, he became a Minister in the French government. This was the first time an African was elected to such a high position in France. One of his main achievements was creating an organization for the Sahara regions. This helped keep the French Union strong.

He also served as Minister of Public Health and Population in 1957. He helped create the Bureau of French Overseas Students and the University of Dakar. In 1958, he helped write the Constitution of the Fifth Republic. His last job in France was Minister-Counsellor until 1961.

Path to Independence

Until the mid-1950s, French colonies in West and Central Africa were grouped into two large federations. Ivory Coast was part of the French West Africa federation and paid for about two-thirds of its budget. Houphouët-Boigny wanted Ivory Coast to be free from this group. He believed in an Africa made of separate nations that could create their own wealth.

He helped create the Loi Cadre, a French law that gave African colonies more self-rule. This law also broke the ties between the different territories, giving them more independence through local assemblies. Not all African leaders agreed with this. Some, like Léopold Sédar Senghor of Senegal, thought it would weaken Africa by dividing it.

After the Loi Cadre was passed in 1956, the PDCI won many seats in Ivory Coast's elections in 1957. Houphouët-Boigny was already a minister in France, president of the local assembly, and mayor of Abidjan. He chose Auguste Denise to be the Vice President of the Government Council of Ivory Coast. Houphouët-Boigny was so popular that his photo was everywhere in Ivory Coast by 1956.

Unlike many African leaders who wanted immediate independence, Houphouët-Boigny wanted a careful transition. He believed that political independence was useless without economic independence. He even challenged Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana to see whose approach to independence would be better in 10 years.

On September 28, 1958, Charles de Gaulle proposed a referendum to the French-African community. Territories could either support a new constitution or declare independence and be cut off from France. Houphouët-Boigny's choice was clear: Ivory Coast would join the French-African community. Only Guinea chose full independence.

Two months after the referendum, seven French West African states, including Ivory Coast, became self-governing republics within the French Community. Houphouët-Boigny had won his goal of separate nations. This helped create the "Ivorian miracle" because the country's income grew greatly between 1957 and 1959.

Houphouët-Boigny wanted to stop Senegal from becoming too powerful in West Africa. He refused to join a conference in Dakar in 1958 that aimed to create a federation of French-speaking African states. Although that federation never happened, Senegal and Mali formed their own union. Houphouët-Boigny worked with France to convince Upper Volta, Dahomey, and Niger to leave the Mali Federation, which then collapsed in August 1960.

President of Côte d'Ivoire

First Years as President

Houphouët-Boigny officially became the head of Ivory Coast's government on May 1, 1959. Even though his party, the PDCI, was the main party, he faced some opposition from within his own government. Some radical nationalists, like Jean-Baptiste Mockey, didn't like his pro-French policies. To solve this, Houphouët-Boigny sent Mockey away in September 1959, claiming Mockey tried to harm him using voodoo in what he called the "black cat conspiracy."

After Ivory Coast gained independence from France on August 7, 1960, Houphouët-Boigny started writing a new constitution. It gave a lot of power to the president and limited the power of the legislature. On November 27, 1960, Houphouët-Boigny was elected President of the Republic without anyone running against him. His party's candidates were also elected to the National Assembly.

The year 1963 saw several alleged plots, which helped Houphouët-Boigny gain even more power. It's not clear if these plots were real or part of his plan to strengthen his control. Many political figures were arrested and tried in secret. There was also some unrest in the army.

For the next 27 years, almost all power in Ivory Coast was held by Houphouët-Boigny. From 1965 to 1985, he was reelected five times without opposition. He and his party believed that national unity was the same as supporting the PDCI. They thought a system with many parties would waste resources and harm the country. So, all adult citizens were required to be members of the PDCI. The media was also strictly controlled and mainly used to spread government messages.

Even though Houphouët-Boigny's rule was authoritarian, it was not as harsh as other African governments at the time. Once he had full power, he released political prisoners in 1967. He handled disagreements by offering government jobs to his critics instead of putting them in jail. Because of this, he was never seriously challenged after 1963. Ivory Coast under Houphouët-Boigny was more tolerant and open than many other post-colonial African countries.

To prevent any attempts to overthrow him, the president took control of the military and police, reducing their size. France helped with defense, keeping its armed forces in Ivory Coast. They could step in if Houphouët-Boigny asked or if French interests were at risk. They intervened during attempts by some groups to break away from the country.

Houphouët-Boigny married Marie-Thérèse Houphouët-Boigny in 1962, after divorcing his first wife in 1952. They did not have children together but adopted one, Olivier Antoine.

Leadership in Africa

Houphouët-Boigny did not agree with Kwame Nkrumah's idea of a "United States of Africa." He felt it would threaten Ivory Coast's newly gained independence. However, he was open to African organizations if he could influence them.

In 1959, he created the Conseil de l'Entente (Council of Understanding) with leaders from Niger, Upper Volta, and Dahomey. This group aimed to share public services, provide a fund for member countries (mostly paid for by Ivory Coast), and offer low-interest loans for development projects. In 1966, he even offered to give dual citizenship to people from these countries, but this idea was dropped after public protests.

He had bigger plans for French-speaking Africa. In 1961, he helped create the Union africaine et malgache (UAM), which included 12 French-speaking countries. They signed agreements on economic, military, and communication matters. However, when the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) was formed in 1963, it pushed for all regional groups like the UAM to be dissolved. Houphouët-Boigny reluctantly agreed and changed the UAM into an organization for economic and cultural cooperation.

Believing the OAU was not effective, Houphouët-Boigny created l'Organisation commune africaine et malgache (OCAM) in 1965. This group aimed to stop revolutionary ideas in Africa. But over time, it became too dependent on France, and many countries left.

In the mid-1970s, Houphouët-Boigny and Senghor worked together to counter Nigeria's growing influence in West Africa. They created the Economic Community of West Africa. Later, they decided to merge their organization into the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) in 1975.

=Françafrique and Foreign Relations

Throughout his presidency, Houphouët-Boigny relied on French advisors. This policy, called "Françafrique", meant he kept very close ties with France, making Ivory Coast France's main African ally. They supported each other unconditionally. He became close friends with Jacques Foccart, France's chief advisor on African policy.

Dealing with Other African Leaders

When Ahmed Sékou Touré of Guinea chose full independence from France in 1958, he challenged both de Gaulle and Houphouët-Boigny. Tensions grew between them. Houphouët-Boigny even helped groups trying to overthrow Sékou Touré.

His relationship with Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana also worsened. Nkrumah supported Sékou Touré and even helped a group trying to break away from Ivory Coast. Houphouët-Boigny accused Nkrumah of trying to destabilize Ivory Coast. When Nkrumah was overthrown in a military coup in 1966, Houphouët-Boigny allowed the plotters to use Ivory Coast as a base.

Houphouët-Boigny also supported efforts to fight against Marxist groups in Africa. He helped Jonas Savimbi's UNITA party in Angola during the Angolan Civil War.

Despite his involvement in some regime changes, Houphouët-Boigny gave refuge to Jean-Bédel Bokassa, the overthrown dictator of the Central African Republic, in 1979. This caused international criticism, and Bokassa became a burden, so he was expelled from Ivory Coast in 1983.

Relations with France and Other Countries

Houphouët-Boigny supported France's actions in Africa. He backed President Joseph Kasa-Vubu during the Congo Crisis in 1960 and later supported Moïse Tshombe. He also played a role in the tensions during the Nigerian Civil War. He supported Biafra's attempt to break away from Nigeria, believing it would weaken the former British colony. However, when other French-aligned countries stopped their support, he also ended his assistance to Biafra.

He began to build relations with South Africa in 1970, even though it had a segregationist government. He believed that problems of racial discrimination should not be solved by force. He met with South African Prime Minister B. J. Vorster in 1977.

Houphouët-Boigny had a difficult relationship with Thomas Sankara, the leader of Burkina Faso. Tensions were high, and Houphouët-Boigny was suspected of involvement in the 1987 coup that overthrew and killed Sankara. It is believed he worked with Blaise Compaoré to achieve this.

He also influenced France to support warlord Charles Taylor's rebels during the First Liberian Civil War. This was in hopes of gaining access to Liberia's resources after the war. He was also secretly involved in arms trafficking to the South African government during its conflict in Angola.

Against the Soviet Union and China

From the start of Ivory Coast's independence, Houphouët-Boigny saw the Soviet Union and China as bad influences on developing countries. He didn't establish diplomatic relations with Moscow until 1967 and then cut them off in 1969. This was after claims that the Soviets supported a student protest in 1968. The two countries didn't restore ties until 1986.

He was even more critical of China, fearing a "Chinese invasion" and colonization of Africa. He worried that Africans would see China's development problems and solutions as similar to their own. Because of this, Ivory Coast was one of the last countries to establish relations with China, doing so in 1983. This meant Ivory Coast stopped its diplomatic ties with Taiwan.

Economic Success and Challenges

Economic Policies in the 1960s and 1970s

Houphouët-Boigny used a system of economic liberalism in Ivory Coast. This helped gain the trust of foreign investors, especially from France. The laws he set up in 1959 allowed foreign businesses to send most of their profits back to their home countries. He also worked to modernize the country's infrastructure, building a business district in Abidjan with luxury hotels.

Ivory Coast's economy grew by 11–12% from 1960 to 1965. The country's total economic output (GDP) grew twelve times between 1960 and 1978. This success came from focusing on farming. Between 1960 and 1970, cocoa production tripled, and coffee production increased by almost 50%.

Because of this economic boom, many immigrants from other West African countries came to Ivory Coast. By 1980, foreign workers, mostly from Burkina Faso, made up over a quarter of the Ivorian population. Both Ivorians and foreigners called Houphouët-Boigny the "Sage of Africa" for this "Ivorian miracle." He was also respectfully nicknamed "The Old One."

However, this economic system, developed with France, had its flaws. Houphouët-Boigny himself said that the economy had "growth without development." It depended on foreign money and ideas and was not truly independent or self-sustaining.

Economic Crisis and Social Tensions

Starting in 1978, Ivory Coast's economy faced a serious decline. This was due to a sharp drop in the international prices of coffee and cocoa. The government tried to protect farmers from this decline, but the country lost a lot of money between 1980 and 1982. From 1983 to 1984, a drought destroyed many forests and coffee and cocoa plants. Houphouët-Boigny tried to negotiate prices with traders in London, but the agreement failed, leading to a major financial crisis.

Even the oil and petrochemical industries were affected by a worldwide economic recession in 1986. Ivory Coast, which had bought farmers' harvests for double the market price, fell into heavy debt. By May 1987, the foreign debt reached US$10 billion. Houphouët-Boigny stopped paying the debt. He also refused to sell his cocoa supply, hoping to raise world prices. This "embargo" did not work. In 1989, he sold his huge stock of cocoa to big businesses to restart the economy.

At this time, he was very ill. He appointed a Prime Minister, Alassane Ouattara, a position that had been empty since 1960. Ouattara put in place strict economic measures to help the country get out of debt.

The good economic times had helped Houphouët-Boigny keep political tensions under control. His relaxed authoritarian rule, with almost no political prisoners, was accepted by the people. However, the economic crisis of the 1980s caused living conditions to worsen for many people. The number of people living below the poverty line increased significantly. The government struggled to control rising unemployment and business failures.

Strong social unrest shook the country. The army had mutinies in 1990 and 1992. On March 2, 1990, large protests took place in Abidjan, with people calling Houphouët a "thief" and "corrupt." These protests led the president to allow multiple political parties and trade unions on May 31.

Political Opposition

Laurent Gbagbo became known as a leader of student protests in 1982. These protests led to the closing of universities. Soon after, he and his wife formed the Ivorian Popular Front (FPI). Gbagbo went to France later that year, where he promoted his party. The French government tried to ignore Gbagbo to please Houphouët-Boigny. Gbagbo eventually got political refugee status in France in 1985. However, the French government tried to pressure him to return to Ivory Coast, as Houphouët-Boigny felt Gbagbo would be less of a threat in Abidjan than in Paris.

In 1988, Gbagbo returned to Ivory Coast. In 1990, Houphouët-Boigny made opposition parties legal. On October 28, 1990, a presidential election was held. Gbagbo ran against Houphouët-Boigny, which was the first time Houphouët-Boigny faced a real challenge. Gbagbo pointed out the president's age, suggesting the 85-year-old wouldn't last another term. Houphouët-Boigny responded by showing old videos of himself looking young. He defeated Gbagbo with an overwhelming 81.7 percent of the votes.

Displays of Wealth

During his presidency, Houphouët-Boigny greatly benefited from Ivory Coast's wealth. By the time he died in 1993, his personal fortune was estimated to be between US$7 and $11 billion. He once said, "People are surprised that I like gold. It's just that I was born in it." He owned many properties in Paris, a property in Italy, and a house in Switzerland. He also owned real estate companies and had shares in famous jewelry and watch companies. He kept his money in Switzerland, saying, "is there any serious man on Earth not stocking parts of his fortune in Switzerland."

In 1983, Houphouët-Boigny moved the capital from Abidjan to Yamoussoukro, his hometown. There, he built many grand buildings at the state's expense, like a polytechnic institute and an international airport. The most lavish project was the Basilica of Our Lady of Peace of Yamoussoukro. It is currently the largest church in the world. Houphouët-Boigny personally paid for its construction, which cost about US$150–200 million. He offered it to Pope John Paul II as a "personal gift." The Pope consecrated it in 1990. However, because of the country's economic problems and the huge cost, the Basilica was criticized and called "the basilica in the bush" by some news agencies.

Death and Legacy

Succession and Passing

The country's political, social, and economic problems also affected who would take over after Houphouët-Boigny. After breaking ties with his previous chosen successor, Philippe Yacé, in 1980, Houphouët-Boigny waited a long time to officially name a new one. The president's health became very weak, and Prime Minister Alassane Ouattara managed the country from 1990 while the president was in the hospital in France.

There was a power struggle, which ended when Houphouët-Boigny chose Henri Konan Bédié, the President of the National Assembly, as his successor. In December 1993, Houphouët-Boigny, who had prostate cancer, was flown back to Ivory Coast so he could die in his home country. He was kept on life support to make sure his final wishes about his successor were clear. After his family agreed, Houphouët-Boigny was disconnected from life support on December 7, 1993. At the time of his death, he was the longest-serving leader in Africa and the third longest-serving in the world.

Houphouët-Boigny did not leave a written will or a clear plan for Ivory Coast after his death. His recognized heirs fought against the government to get back part of his huge fortune, claiming it was "private" and not state property.

Funeral and Impact

After Houphouët-Boigny's death, the country remained stable, which was shown by his impressive funeral on February 7, 1994. The funeral for this "doyen of francophone Africa" was held in the Basilica of Our Lady of Peace. There were 7,000 guests inside and tens of thousands outside. The two-month delay before the funeral is a tradition among the Baoulé ethnic group and allowed for many ceremonies. The funeral included traditional African customs, like a large choir singing in Baoulé and village chiefs displaying special cloths.

Over 140 countries and international organizations sent representatives to the funeral. However, many Ivorians were disappointed by the low attendance from some key allies, especially the United States. In contrast, Houphouët-Boigny's close ties with France were clear from the large French group that attended, including President François Mitterrand and many other important figures. His death marked the end of an era and perhaps the end of the very close French-African relationship he represented.

Félix Houphouët-Boigny Peace Prize

To leave a legacy as a man of peace, Houphouët-Boigny created an award in 1989. This prize is supported by UNESCO and funded by the Félix-Houphouët-Boigny Foundation. It honors people who work for peace. The prize is named after him because he was a "tireless advocate of peace, harmony, friendship, and dialogue to solve all conflicts."

It is given out every year along with €122,000. An international jury of 11 people from five continents, led by former United States Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, chooses the winner. The prize was first given in 1991 to Nelson Mandela and F. W. de Klerk of South Africa. It has been awarded every year since, except for 2001 and 2004.

Positions in Government

France

| Position | Start date | End date |

|---|---|---|

| Member of French National Assembly | various | various |

| Member of the Council of Ministers under Prime Minister Guy Mollet | 1 February 1956 | 13 June 1957 |

| Minister of State under Prime Minister Maurice Bourgès-Maunoury | 13 June 1957 | 6 November 1957 |

| Minister of Public Health and Population under Prime Minister Félix Gaillard | 6 November 1957 | 14 May 1958 |

| Minister of State under Prime Minister Pierre Pflimlin | 14 May 1958 | 17 May 1958 |

| Minister of State under Prime Minister Charles de Gaulle | 1 June 1958 | 8 January 1959 |

| Minister of State under Prime Minister Michel Debré | 8 January 1959 | 20 May 1959 |

| Advising minister under Prime Minister Debré | 23 July 1959 | 19 May 1961 |

Côte d'Ivoire

| Position | Start date | End date |

|---|---|---|

| President of the Territorial Assembly | 24 March 1953 | 30 November 1959 |

| Governor of Abidjan | 1956 | 1960 |

| Prime Minister | 1 May 1959 | 3 November 1960 |

| Minister of Interior | 8 September 1959 | 3 January 1961 |

| President of the Republic, Minister of Foreign Affairs | 3 January 1961 | 10 September 1963 |

| President of the Republic, Minister of Defense, Minister of Interior, Minister of Agriculture | 10 September 1963 | 21 January 1966 |

| President of the Republic, Minister of Economy and Finances, Minister of Defense, Minister of Agriculture | 21 January 1966 | 23 September 1968 |

| President of the Republic | 23 September 1968 | 5 January 1970 |

| President of the Republic | 5 January 1970 | 8 June 1971 |

| President of the Republic, Minister of National Education | 8 June 1971 | 1 December 1971 |

| President of the Republic | 1 December 1971 | 7 December 1993 |

See also

In Spanish: Félix Houphouët-Boigny para niños

In Spanish: Félix Houphouët-Boigny para niños