Farewell Priory facts for kids

St Bartholomew's Church, Farewell, today. It incorporates some of the medieval stonework at the eastern end.

|

|

| Monastery information | |

|---|---|

| Full name | Convent of St. Mary, Farewell |

| Order | Benedictine |

| Established | Mid-12th century |

| Disestablished | 1527 |

| Dedicated to | Mary, mother of Jesus |

| Diocese | Diocese of Coventry and Lichfield |

| Controlled churches | Farewell |

| People | |

| Founder(s) | Roger de Clinton |

| Important associated figures |

|

| Site | |

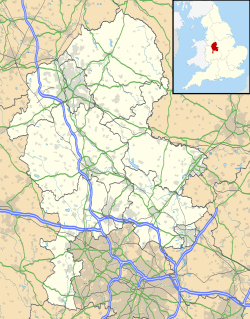

| Location | Farewell near Lichfield |

| Coordinates | 52°42′08″N 1°52′42″W / 52.7023°N 1.8783°W |

| Public access | Site open to public. Church in use. |

|

Listed Building – Grade II*

|

|

| Official name: Church of St Bartholomew | |

| Designated: | 27 February 1964 |

| Reference #: | 1374273 |

Farewell Priory was a Benedictine nunnery (a place where nuns lived) located near Lichfield in Staffordshire, England. It was a small and not very wealthy priory. Even though it received support from bishops, it was closed down in 1527. This happened because Cardinal Wolsey wanted to create a new college at Oxford University.

Contents

Discovering Farewell Priory's History

How Farewell Priory Started

A religious community began at Farewell around the mid-1100s. It was founded by Roger de Clinton, who was the Bishop of Lichfield and Coventry from 1129 to 1148.

At first, this place was called an abbey and was home to male hermits (people who lived alone for religious reasons). Bishop Roger's early documents suggest they were canons regular, possibly Augustinian monks. They lived in an area called Chirstalleia, which is now Chestall, near Cannock Wood.

Later, Bishop Roger decided to change things. He transferred the church and lands to a community of women, making it a nunnery. It's not clear what happened to the male hermits.

What Kind of Order Was It?

Farewell Priory was officially known as a Benedictine priory in church records. When it closed, the nuns were sent to other Benedictine houses.

However, there was some confusion. In 1425, it was called Cistercian in a bishop's register. This might have been because Langley Priory, a daughter house of Farewell, sometimes claimed to be Cistercian. They did this to avoid paying tithes (church taxes) that Cistercian houses didn't have to pay.

Pope Alexander III even ordered an investigation into this claim. In the end, Langley Priory had to give up some land and pay money to keep their tax exemption.

Royal Support for the Priory

In 1398, King Richard II said Farewell Priory was "in the king's patronage." This meant the king supported it. However, this was a rare event. The priory was mainly supported by the bishop, who also played a big part in its closing.

Farewell Priory and Its Daughter House

Langley Priory was started with nuns from Farewell. This was confirmed in a document from William de Ferrers, 3rd Earl of Derby around 1180.

Farewell Priory had some control over Langley. Around 1210, the prioress (the head nun) of Farewell could take part in choosing the new prioress of Langley. But if she didn't show up, the election would still happen.

Later, in 1248, an agreement was made. Langley Priory had to pay Farewell 4 marks (a type of money) each year. This helped settle their disagreements.

Lands and Property of Farewell Priory

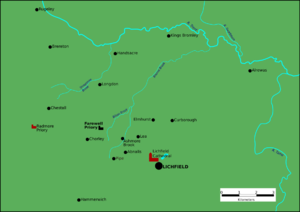

Bishop Roger de Clinton's first gift to the nuns included the church of St Mary at Farewell, a mill, and a wood. They also received land between two streams and the service of six families of serfs (people who worked the land for a lord).

Other people also donated land. Hugh, the bishop's chaplain, gave land at Pipe. Hamminch of Hammerwich gave half a hide of land (an old measure of land).

Walter Durdent, the next bishop, added more land and services to the priory. These gifts were clearly for the "nuns of Farewell."

Royal Confirmations of Land

King Henry II also supported the nuns. In 1155, he confirmed their ownership of several properties and rights:

- Their abbey at Farewell in the royal forest of Cannock.

- Land at Farewell with mills.

- More land at Farewell given by Robert the reeve and his son.

- Marshland that could be used for meadows.

- Land at Pipe and Hammerwich, including people who lived there.

- 40 acres at Lindhurst in the king's manor of Alrewas.

- A promise to accept any future gifts to the priory.

- Freedom from many taxes and court duties.

Around 1170, Geoffrey Peche gave land at "Morhale" as a dowry for his daughter, Sara, when she joined Farewell. This was a common way for nunneries to receive small gifts.

On April 3, 1200, King John confirmed all the grants his father, Henry II, had made. He also referred to the nunnery as an "abbey." In the same year, Farewell was one of the nunneries that received money from the king.

Later Land Acquisitions

In 1251, King Henry III confirmed that Farewell Priory did not have to pay certain fees for their animals in Cannock Forest.

The priory also held other small estates. They had land at Chorley and a house in Lichfield. They also owned land at Curborough.

In the 1300s, the priory continued to gain and protect its lands. By 1399, they had six properties in Lichfield. In 1321, Philip de Somerville gave them 20 acres of land at Alrewas.

In 1353, Prioress Margaret tried to get back land at Elmhurst. She claimed that John West of Elmhurst had held the land from her.

In 1375, King Edward III confirmed Henry II's charter again. In 1398, the priory was allowed to acquire more properties worth 10 marks a year.

Priory Holdings at Dissolution

When the priory closed in 1527, its lands included:

- Farewell and Chorley: three houses, a cottage, a water-mill, and 1400 acres of land.

- Curborough, Elmhurst, Lea, Lenthurst, Alrewas: two houses and 470 acres.

- Hammerwich: a house and 50 acres.

- Ashmore Brook: a house and 40 acres.

- Lichfield: three houses.

- Kings Bromley: 11 acres.

- Water Eaton: one house, a small field, and 22 acres.

- Cannock, Abnalls, Pipe and Burntwood: 140 acres.

- Rugeley, Brereton, Handsacre: 20 acres.

- Oakley: 6 acres of meadow.

- Tipton: a mill and 26 acres.

The priory's estates were mostly close together. In the early 1300s, they farmed their own land at Farewell, Curborough, and Hammerwich. Later, they started raising sheep, which was a common change as labor costs increased.

Life at Farewell Priory

We know about the daily life at Farewell Priory mainly from two official visits by bishops in the 1300s. These visits often focused on areas that needed improvement.

Bishop Northburgh's Visit (1331)

Roger Northburgh visited in 1331. He wrote his instructions in French because the nuns did not understand Latin. It seems they had not followed earlier Latin rules.

- Two nuns had left the convent.

- The bishop wanted proper financial records from the convent officials.

- He told the nuns to stop wearing fancy clothes like silk belts and purses. They should choose an older nun to manage their clothing.

- Nuns were not allowed to sleep with each other or with young girls in the dormitory.

- Two servants had to leave the house. Only young women who planned to become nuns could stay there.

- A back door had to be kept locked to prevent problems.

Bishop Stretton's Visit (1357)

Robert de Stretton visited in 1357 and issued his rules in 1358. Some of the same issues came up again.

- Nuns were warned not to go to Lichfield without permission from the prioress. They had to be with two other nuns and couldn't stay long in town.

- Nuns were not allowed to leave the priory grounds at all without permission.

- No non-religious women should live on the premises without the bishop's permission.

- The same rule applied to unauthorized children. Each nun could keep one child for education with the bishop's permission, but boys over seven years old were not allowed.

- The bishop demanded that nuns follow their vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience.

- The prioress and officials had to present financial accounts at least once a year.

- Nuns were to eat together in the prioress's hall, as separate food portions were too expensive.

- The only fire allowed was in the building for guests or the sick.

- Priory property could not be given away without the bishop's permission.

- The bishop's rules were to be read and explained in English by a literate cleric.

The End of Farewell Priory

Cardinal Wolsey was a powerful figure who didn't like how many monasteries were run in the early 1500s. In 1518, he received permission from the Pope to visit all monasteries in England.

In 1524, Wolsey, who was also the Lord Chancellor and Archbishop of York, wanted to close the Priory of St Frideswide in Oxford. He planned to use its money to fund a new college at Oxford University called Cardinal College, named after himself.

To get enough money for his college, he decided to close several other monasteries across the country. In September 1524, Pope Clement VII approved Wolsey's plan to take over more religious houses. At first, Farewell Priory was not on the list.

However, in 1527, Farewell Priory was closed. Its income was given to Lichfield Cathedral to support its choristers (choir singers). The main reason for this seems to be that Wolsey needed to pay a debt he owed to Lichfield related to his college plan.

Wolsey's order to close Farewell Priory was issued on March 20, 1527, with approval from King Henry VIII. The order stated that the nuns should be moved to other Benedictine houses. The priory's assets were to go to the dean and chapter of Lichfield Cathedral.

The closure happened on April 13, 1527. The last prioress, Elizabeth Kilshawe, had lands and properties worth about £33. It seems the nuns were indeed transferred. One nun, Felicia Bagshawe, went to Black Ladies Priory. She stayed there until it also closed in 1538, receiving a small payment and then a yearly pension. Prioress Elizabeth was moved to Nuneaton Priory.

On August 18, 1527, Farewell Priory and all its possessions were formally given to the dean and chapter of Lichfield Cathedral. This shows that the bishop continued to support Farewell, as it returned to the diocese after it closed.

In 1535, a survey called the Valor Ecclesiasticus valued the choristers' endowment at almost £40. Most of this, nearly £25, came from the former Farewell Priory estates.

In 1550, the Dean and Chapter of Lichfield granted the lands of the former priory to William, Lord Paget. In 1564, his son, Henry Paget, 2nd Baron Paget, officially registered his right to the old priory lands.

The priory buildings themselves seem to have disappeared by the 1700s. The local parish church was changed a lot in the 1740s and again in the mid-1800s. Only the eastern part of the original structure remains. During the 1700s renovation, some old earthenware pots were found in the church walls. A sketch of one was published in The Gentleman's Magazine in 1771.

Prioresses of Farewell Priory

Here is a list of the known prioresses of Farewell Priory:

- Serena (around 1248): She made an agreement with Langley Priory.

- Julia (during Henry III's reign): Mentioned in a lawsuit.

- Maud (early 1270s).

- Margery (1293).

- Mabel (died 1313).

- Iseult of Pipe (elected 1313, resigned 1321).

- Margaret de Muneworth (appointed 1321): She sued for land in 1353.

- Sibyl (around 1357).

- Agnes Foljambe (around 1367): Sued over land.

- Agnes Turville (resigned 1398).

- Agnes Kyngheley (elected 1398).

- Margaret Podmore (died 1425).

- Alice Wolaston (elected 1425): She sued someone in 1462.

- Anne (1476).

- Elizabeth Kylshaw (first mentioned 1523): She was the last prioress when the priory closed in 1527. She was then moved to Nuneaton Priory.

Images for kids