Fitzroy Iron Works facts for kids

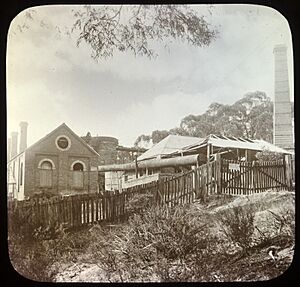

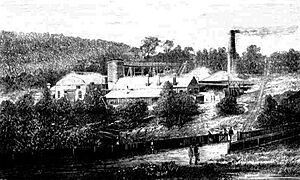

The Fitzroy Iron Works near Mittagong, New South Wales, was Australia's very first factory to commercially smelt iron. It started working in 1848.

For many years, from 1848 to about 1910, different owners tried to make the iron works profitable. But sadly, none of them succeeded. It seemed like new managers often made the same mistakes as the old ones. Because of this, the Fitzroy Iron Works became known for missed chances, repeated failures, and money lost.

Even though it faced many challenges and closed several times, the Fitzroy Iron Works was important. It helped set the stage for Australia's future success in making iron and steel. It also played a big part in helping the town of Mittagong grow.

In 2004, during building work, parts of the old iron works were found. These old pieces have been saved and are now on display. You can also see some remains and a special monument at the site of the old blast furnace.

Contents

- Where was the Fitzroy Iron Works?

- History of the Iron Works

- Finding the Iron Ore (1833)

- Early Days and First Iron (1848–1851)

- New Company, More Problems (1851–1854)

- Iron & Coal Mining Company (1854–1858)

- Fitzroy Iron Works Company (1859–1869)

- Lattin and Hughes (1863-1864)

- The First Blast Furnace (1864–1866)

- Ebenezer Vickery's Influence

- Local Competition

- Operational Problems (1865–1866)

- Levick's Furnace Changes (1868–1869)

- Hughes Brothers (1868)

- Bladen and Company (1868)

- Puddling, Shingling, and Rolling (1868)

- Casting Operations (1865–1866)

- Brickmaking

- Looking for New Money (1870–1872)

- Fitzroy Bessemer Steel, Hematite, Iron and Coal Company (1873–1883)

- Mittagong Land Company and Final Years (1883–1910)

- Finding Old Remains

- Legacy and What's Left

- Images for kids

Where was the Fitzroy Iron Works?

The Fitzroy Iron Works was located just southwest of the modern-day Mittagong town. The original iron ore was found south of the Main Road. The factory itself was built on the north side of the Old Hume Highway and Mt Alexander.

History of the Iron Works

Finding the Iron Ore (1833)

In 1833, a surveyor named Jacques noticed iron ore while working on a new road to Berrima. The ore was found near a bridge, which was later called Ironstone Bridge. This area also had special mineral springs rich in iron. The iron ore here was very good, with 44% to 57% pure iron. This was a high amount compared to other places at the time.

Early Days and First Iron (1848–1851)

In 1848, a local man, John Thomas Neale, and two brothers, Thomas Tipple Smith and William Tipple Smith, teamed up with a Sydney businessman, Thomas Holmes. They wanted to use the iron ore. William Tipple Smith was known for finding gold in 1848, even before the famous New South Wales gold rush started in 1851.

They hired William Povey, an expert in iron works, to manage the factory. By late 1848, they had sent some iron samples to Sydney. This was not the first time iron was made from Australian ore. But it was the first time it was made for sale in Australia.

In February 1849, a report said they were using a "Cataline furnace." This was a type of bloomery furnace called a Catalan forge. It blew air under pressure, making it more advanced than older bloomery furnaces. They used charcoal as fuel. A Catalan forge didn't melt the iron completely. Instead, it made "sponge iron," which was a semi-solid lump called a "bloom." This sponge iron could then be shaped into wrought iron or melted to make cast-iron products. By the mid-1800s, this type of furnace was already old-fashioned. But it was simple to build and use.

The first iron samples in 1848 were probably shaped by hand, like a blacksmith would. This is because the factory didn't have a large mechanical hammer, called a tilt hammer, until 1852.

Governor FitzRoy visited the works in January 1849. He was given a special knife with many tools, made from local steel and mounted in local gold. The partners named their factory the Fitz Roy Iron Mine in his honor. Before that, it was called the Ironstone Bridge Ironworks.

The partners then tried to get more money to make the factory bigger. They released a plan for the Fitz Roy Iron Mine Company in February 1849.

By March 1850, when Governor FitzRoy visited again, they were digging ore, making bricks, and building a larger Catalan forge. They had also built a cupola furnace and a foundry to make cast-iron. A tilt hammer was on its way from England. A tilt hammer was a big, powerful hammer used to shape the sponge iron into wrought iron. This process was called "shingling."

To celebrate Governor FitzRoy's visit in March 1850, they made fifty cast-iron doorstops. They were shaped like a lion standing up. The lion was a symbol of the FitzRoy family. These doorstops were made from imported iron melted in the cupola furnace.

New Company, More Problems (1851–1854)

One of the first partners, John Neale, left. Fifteen new shareholders joined the Fitzroy Iron Mine Company, which officially started on September 16, 1851. William Tipple Smith had a stroke in 1849 and was not active in the new company. He died in 1852.

By September 1852, the tilt hammer and its powerful engine were being set up. The company had made about 100 iron lumps (blooms), weighing two tons in total. But then, the tilt hammer, which was very important, broke and couldn't be fixed. It also became clear that using charcoal as fuel was too expensive. They needed to produce much more iron to make a profit.

Iron & Coal Mining Company (1854–1858)

In 1854, the company got more money and changed its name to the Fitz Roy Iron & Coal Mining Company. This was so they could order rolling equipment from England. A Sydney merchant, Frederick John Rothery, became the biggest shareholder and chairman. They tried to sell more shares to the public, but it didn't go as well as they hoped. So, they took out a loan for £6,000, with the directors personally responsible for it. Rothery later lent the company another £3,500.

The company bought three new tilt hammers from Mr. Povey for £1,000. Povey had brought them from England 16 months earlier. He also agreed to buy £500 worth of shares in the new company.

In 1855, the company used its cupola furnace as a small blast furnace to make some pig-iron from iron ore. This pig-iron was then "puddled" (cleaned) and sent to P. N. Russell & Co. in Sydney. There, it was used to make anchors, which were shown at the 1855 Paris Exhibition. This was likely the first time pig-iron was made from Australian iron ore.

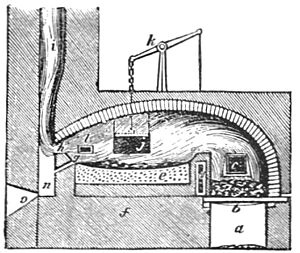

The new directors asked James Henry Thomas, an engineer, to report on the mines and machinery. In August 1855, the board decided not to build a large blast furnace because it was too expensive. Instead, they decided to build six puddling furnaces and one reheat furnace. They planned to use these puddling furnaces to directly smelt the ore. Thomas explained that this method was cheaper to set up than a blast furnace.

A reverberatory furnace used coal as fuel, which was easier than making coke for a blast furnace. This might have been another reason for their decision. The main goal was to get iron to the Sydney market, even if it was in small amounts.

The company started looking for coal supplies for the new furnaces and rolling mills. Getting the iron to Sydney was also hard because there was no railway yet.

Then, there was a lot of disagreement between the directors and other shareholders. The factory kept working, but no real improvements were made. By 1855, only three tons of wrought iron had been made in total. When the chairman resigned in 1856 and tried to take over the factory due to the loan, operations stopped.

In April 1856, William Povey became the first person to go bankrupt because of his involvement with the iron works.

In 1857, a shareholder named William Henry Johnson bought the factory's assets. He couldn't restart the company, but he did install the rolling mill that had been ordered earlier. This was the first rolling mill in Australia for making wrought iron products. But it sat idle and wasn't the first to actually produce iron.

Around July 1858, they tried smelting ore again. They made 16 hundredweight of "No. 1 iron" from about 2.5 tons of ore. This "blast furnace" was probably the existing cupola furnace. The factory still didn't have a proper blast furnace, which was the most important first step in making iron commercially. However, it had all the other parts of an iron works.

The discovery of coal nearby in 1853 and the railway getting closer to Mittagong made people hopeful again. They thought a blast furnace could finally make a profit. Johnson got promises of money from others and kept trying to start a new company. More money was always needed for any progress.

Fitzroy Iron Works Company (1859–1869)

Even with past failures, people saw the potential of the mine and the growing railways. They thought the factory could make iron rails and be successful. In December 1859, a plan for the 'Fitz Roy Ironworks Company' was published. It included a report praising the ore and the iron made from it. It also mentioned that the iron would be used to fix railway machines.

The new company didn't raise enough money. It was restarted in 1862–1863 as the Fitz Roy Iron Works Company. Four important new shareholders joined: John Keep, John Frazer, Simon Zöllner, and Ebenezer Vickery. Only Simon Zöllner had worked in the iron industry before. John Keep was an ironmonger (someone who sells iron goods), and Vickery had learned about ironmongery when he was young.

In late 1862, the company tried to get a contract from the New South Wales Government to supply 10,000 tons of iron rails for new railways. The price was to be £12 per ton, the same as imported English rails. But the factory needed more investment to start making iron on a larger scale.

Lattin and Hughes (1863-1864)

Benjamin Wright Lattin, a former grocer from Melbourne, leased the Fitzroy Iron Works in early 1863. He agreed to build a blast furnace that could make 120 to 150 tons of iron per week. In return, he would get shares in the company. Lattin chose Enoch Hughes to oversee the furnace's construction. Hughes was already the works manager in October 1862.

The company's deal with Lattin was that he would fix up the works to produce a certain amount of iron. If he succeeded, he would get 2,000 paid-up shares. If not, he would get nothing. Lattin expected to spend £12,000 to £13,000.

They planned to start the rail contract in April 1863, but no rails were made during Lattin's 12-month lease. The blast furnace took longer to build than Hughes thought. Lattin needed money quickly. So, they bought scrap iron for £4 per ton and used the existing factory to re-roll it into bars. The first iron bars made at Fitzroy Iron Works were available in Sydney in December 1863. They were making about 36 tons per week, which later dropped to 30 tons per week.

As the blast furnace was being built, they prepared for its operation. They advertised for limestone and coal miners in early 1864. A 2.5-mile-long tramway, pulled by horses, was built to bring coal from the Nattai Gorge.

The blast furnace was not finished when Lattin's contract ended on April 1, 1864. Hughes left around this time. The directors hired Joseph Kaye Hampshire, an experienced English ironmaster, and engineer Frederick Davy. Hampshire had helped build the blowing equipment for Lattin in England.

Lattin stayed for a short time but left when his financial problems grew. In August 1864, soon after the blast furnace was first lit, Lattin was in serious debt. He claimed he had spent over £25,000 on the furnace and other works, which was double what was expected, and he had lost it all.

The First Blast Furnace (1864–1866)

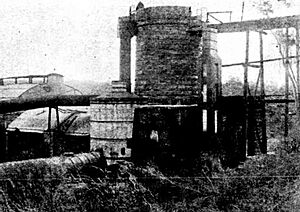

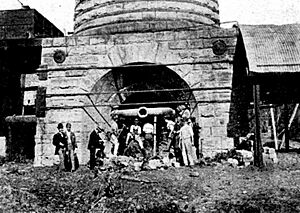

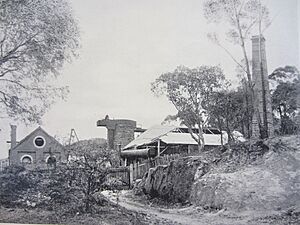

Enoch Hughes knew about iron working, but not much about operating blast furnaces. The furnace he built was an old design, similar to Scottish ones from the 1830s. It was a "cold blast" furnace with an open top. The outside was made of sandstone blocks, standing 46 feet tall. It was lined with fire-bricks made at the factory from local clay.

The blast furnace was at the bottom of a hill, about 250 yards east of the rest of the factory (puddling furnaces, foundry, and rolling mill). This area became known as 'the top works'. Workers could reach the top of the furnace from the hill using a wooden walkway. The furnace top had a platform and three openings to add ore and other materials.

On July 30, 1864, Australia's first blast furnace made pig-iron under Hampshire's management. But problems started right away. Moisture in the foundations and lining turned into steam, cooling the iron and stopping it from flowing out. The furnace had to be shut down. They had to pull out the half-melted iron with hooks and bars. In September 1864, the company admitted to "difficulties" and said they were changing the furnace to "hot-blast" operation. Only 80 tons of iron were made using the cold-blast method.

They dug drainage trenches around the furnace base. The furnace was relined with new fire-bricks, and one 'stove' was added to heat the air blast. Hampshire designed and oversaw these hot-blast changes himself, improving the old cold-blast furnace.

The upgraded blast furnace first made pig-iron with a hot blast on May 2, 1865. Even though problems would come later, the furnace initially made about 90 tons of iron per week. Hampshire said the ore, after being roasted to remove moisture, produced 60% metal, showing its high iron content.

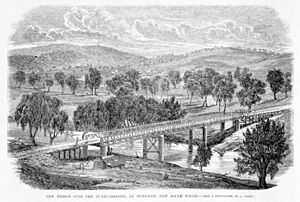

This early success was just in time. The factory had a contract to supply castings for the columns of the Prince Alfred Bridge at Gundagai. They had been so slow that bridge construction was affected. The first castings were made with cold-blast iron, but more iron was needed to finish the job.

The blast furnace had made 2,394 tons of iron before it was shut down in January 1866.

Ebenezer Vickery's Influence

Ebenezer Vickery, a Sydney businessman, became chairman of the Fitzroy Iron Works Company. He was the main leader after Benjamin Lattin's contract ended. Vickery was a Methodist. He believed in good morals for his workers and the town. During his time, public buildings were built in Mittagong. Between 600 and 700 people (workers and their families) depended on the factory's wages.

Vickery promoted Fitzroy iron by using it himself. He used it for the roof trusses of Mittagong's Methodist church and in his own building in Sydney.

He tried to improve the company's finances. In August 1864, they took out a £6,000 loan on the factory. In 1865, they sold building plots in the town of 'New Sheffield' to raise more money. In February 1865, the company's capital was cut in half, which meant writing off much of the earlier investments.

In November 1865, reports said the factory was selling iron to P. N. Russell & Co. and other customers in Melbourne for manufacturing. Larger puddling furnaces were being built, and the rolling mill was being reinstalled on stronger foundations.

However, in December 1865, with ongoing problems at the blast furnace, shareholders voted to merge with P. N. Russell & Co, a large Sydney foundry. This company was a big customer of Fitzroy iron. The merger would have meant George Russell taking over management. An attempt to raise new money in early 1866 to expand the factory (add more blast furnaces and stronger rolling mills) failed. So, the merger didn't happen. Although the factory kept working partly for a few more years, it was completely idle by 1869.

They had tried to keep good relations with the New South Wales Government. The Governor, Sir John Young, visited twice. But when Vickery and his co-directors tried to get a government guarantee for a £50,000 loan in May 1867, it failed. The Premier, James Martin, blamed the company's past problems. This was not helped by Benjamin Lattin revealing his huge losses around this time. Some newspapers also suggested that the main shareholders hadn't risked much of their own money but expected government help. This was denied. The guarantee also faced opposition from those who supported free-trade, fearing the Fitzroy Iron Works would become a monopoly if it got government backing.

The company asked shareholders for more money in August 1868. The end came when the Bank of New South Wales took over the factory due to unpaid loans. The works, 1,000 acres of land, and 3,000 tons of iron were put up for sale in late 1869.

The Fitzroy Iron Works was one of the few failures in Vickery's otherwise very successful business career. He owned parts of several coal mines. He kept an interest in Mittagong and was involved in later companies there. He died in 1906.

Local Competition

In 1865, a large rolling factory called the City Iron Works was set up in Pyrmont, Sydney, by Enoch Hughes. It bought local scrap iron and rolled it into bars, just like Hughes had done at Fitzroy. Being closer to its market and scrap iron, it was immediately successful, making about 20 tons of bars per week.

Operational Problems (1865–1866)

Even after the blast furnace was changed to 'hot-blast', it still had problems. It was an open-top furnace, meaning it couldn't use the waste gases (like carbon monoxide) to fuel boilers or heat the blast. This made it more expensive to run. It also only had one 'stove', so it couldn't apply the hot-blast all the time. This made the iron expensive. In 1865, imported pig-iron cost £5 per ton, while Fitzroy's cost £5 17s 6d.

There were also issues with the furnace itself. Soon after it started, deposits called 'scaffolding' began to build up inside, making the space smaller. Production dropped to just 26 tons per week.

The local coal wouldn't turn into coke, so it was put directly into the blast furnace. This coal was called 'anthracite', perhaps because it was hard to burn or wouldn't form coke. True anthracite coal is rare in New South Wales. It was probably poor quality coal with a lot of ash, which made the furnace problems worse. By June 1865, people were complaining about the coal. Hampshire reportedly had to add charcoal or wood to keep the furnace working.

Limestone, used to help the smelting process, was found at Marulan. But without a railway, it had to be carried by horse-drawn carts. A railway connection to Sydney, the main market, didn't reach Mittagong until March 1867.

In January 1866, the blast furnace was shut down. But other parts of the factory kept working. The company planned to lease out its new puddling furnaces and rolling mill while they fixed the blast furnace, found better coal, and got more money.

The big contract from 1862 to supply 10,000 tons of iron rails, which had led to Lattin's involvement, seemed to be forgotten by both the government and the company.

Joseph Hampshire left the works and died in 1870.

Levick's Furnace Changes (1868–1869)

In December 1867, a new ironmaster, Thomas Levick, arrived from England. He added a second 'stove' to the blast furnace, allowing a continuous hot-blast. He also changed the old furnace to a "closed-top" design. This meant the waste gases could be used as fuel for boilers and to heat the blast. He also fixed the lower part of the furnace, which was cracked and damaged.

Levick's changes were a big improvement, and his knowledge was very helpful. However, in mid-1869, he resigned due to poor health. The blast furnace had not yet restarted when the bank took over the factory in late 1869. The benefits of Levick's changes would only be seen when the furnace was lit again in the 1870s under new management.

Hughes Brothers (1868)

The brothers Enoch and William Hughes, with John Salter, leased the puddling furnaces and rolling mill from February to June 1868. Enoch Hughes had managed for Benjamin Lattin earlier and knew how to roll iron bars from scrap. They processed leftover pig-iron and rolled it into bars. But they found it wasn't profitable. While there, Hughes made the first iron plate rolled in Australia and claimed to have rolled the first rails. Their contract ended in June 1868 because they couldn't get enough money. They produced 164 tons of bars and 30 tons of plate iron, but only sold 66 tons.

Bladen and Company (1868)

Bladen and Co., led by Thomas Bladen, leased the works next. They also processed and rolled iron into bars. They too found it unprofitable. It was reported that Bladen & Co. employed 22 workers in the rolling section.

Puddling, Shingling, and Rolling (1868)

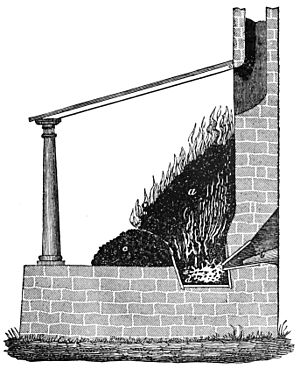

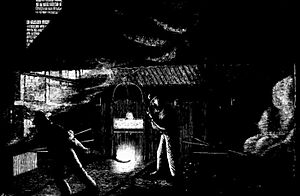

The "puddling" process involved melting pig-iron in a furnace and stirring it to remove carbon. In 1868, there were four puddling furnaces. Two were in use, one was being repaired, and another was used for heating.

The engraving of the puddling furnace shows how molten metal was stirred to mix with air, causing chemical changes. The iron would become pasty, then rolled into balls. These balls weighed 80 to 100 pounds each.

After puddling, the iron balls went to a large "tilt hammer." This hammer weighed about a ton and hit the iron 70 to 80 times a minute. This process, called "shingling," squeezed out waste and impurities. The iron balls became "blooms."

The "blooms" were then passed through rollers to create "puddled bars." These bars were cut into smaller pieces, reheated, and rolled again to make the final products like merchant bars or plates. Different rollers were used for different shapes and sizes.

Casting Operations (1865–1866)

Besides making pig-iron, the factory also cast iron items. The foundry and its cupola furnaces were at the 'top works', near the blast furnace. They cast parts for their own machines, including a seven-ton 'sole plate' for the tilt hammer.

The company also cast the cylindrical casings for the supporting columns of the Prince Alfred Bridge at Gundagai. They also made cast-iron parts for buildings. Casting stopped by April 1866. The last columns for the Gundagai bridge had to be finished by P & N Russell in Sydney.

Brickmaking

The factory made its own bricks from clay found on its land. The clay was ground in a 'Chilean mill'. Bricks were needed to repair the many furnaces.

Looking for New Money (1870–1872)

Why Things Looked Better

When the Fitzroy Iron Works was put up for sale in late 1869, it seemed like the end. But in the early 1870s, things actually looked better for the iron works.

There was a high demand for iron worldwide. In Australia, many factories and foundries were making iron products. But most of the raw iron (pig-iron and wrought iron) was still imported. The New South Wales government generally supported free trade over protecting local industry. However, the demand for iron in Australia became so strong that the price of imported pig-iron jumped from £4 10s per ton in 1870 to £9 per ton in 1873. This made local iron much more competitive.

The railway network in New South Wales was growing, which meant more demand for rails and cheaper, faster transport. The railway reached Mittagong in March 1867 and Marulan (where the old company got its limestone) in August 1868.

The blast furnace had been improved by Levick before the works closed in 1869. Even though it was an old design, it was now much more efficient. The puddling furnaces and rolling mills had been working recently, and there were still experienced workers in the Mittagong area.

Coal was still a problem. But by July 1868, the Cataract Coal Mine had opened near Berrima, and the company saw potential in its coal.

Making rails for the expanding railway network was a big opportunity. But iron rails were becoming old-fashioned. Steel rails were more expensive but lasted longer. In the 1870s, New South Wales railways started using steel rails, which had to be imported from England. Fitzroy's old factory could make wrought iron, but not steel. And its production was small. Making rails would need a lot of money, especially to make steel using the Bessemer process and roll it into heavy rails.

It had always been hard to raise money for the factory in Australia. This became even harder after the bank took over and the factory failed to sell in 1869. In March 1870, the company was ordered to pay back £12,452 11s 6d to the Bank of New South Wales. A meeting was held in February 1870 to close down the Fitzroy Iron Works Company. If the factory was to restart, new money was needed to pay off debts, buy the assets, and cover running costs.

John Frazer's Efforts

Some of the old company's directors still wanted to restart the factory. One of them, John Frazer, a rich Sydney merchant, was in England in July 1870. He tried to get English investors interested in the Mittagong works. By August 1870, it was reported that an English company was being formed. Frazer paid £10,000 to the bank in 1872, clearing the debt. In April 1872, it was announced that the works had been sold to an English company, and an English manager was on his way.

Fitzroy Bessemer Steel, Hematite, Iron and Coal Company (1873–1883)

From 1873 to 1883, the factory was owned by an English company called Fitzroy Bessemer Steel, Hematite, Iron and Coal Company. The company's plan was published in April 1873. The previous owners received cash and shares. So, Ebenezer Vickery, John Frazer, and Simon Zöllner still had an interest in the new company, but they weren't running it day-to-day.

David Smith's Management (1873–1875)

In July 1873, a new English manager, David Smith, arrived with 15 skilled workers and their families. Smith was also a main shareholder. Almost immediately, there were problems between Smith and his new workers.

The new company planned to install a Bessemer Convertor to make steel rails, as its name suggested. But they didn't go ahead with it. Instead, Smith tried to improve the existing factory. Smith finished changing the blast furnace to a "closed-top" design, adding the 'bell top' and its winding equipment. The dam at Lake Alexandra was also built during Smith's time to provide water for the factory.

Smith tried to solve the problems with coking coal that had troubled previous owners. First, he tried to use coal from Black Bob's Creek. But after spending £3,000 on a tramway and winding equipment, he found the coal wasn't suitable for the furnace. It seems the blast furnace was lit in 1874 to test this coal, but it didn't work well. In 1874, the company bought 80 acres near Berrima to access thick seams of coking coal and started digging a mine.

Smith and others in the Berrima area then pushed the government to build a tramway from their Berrima mine to the main railway line. They offered cheaper coal for the government railways. Other mining areas weren't happy, saying other mines had paid for their own tramways and even ports. The government's policy was that branch lines should be paid for by the users. People were also surprised that a line was needed at all, as the factory's managers had always praised the quality of the coal on their Mittagong land, only to now say it was useless for ironmaking.

In October 1875, Smith complained bitterly about the New South Wales Government's "shabby treatment." He was upset that they didn't build the branch line to the Berrima coal mine, bought lower quality imported rails, and charged high rates for rail freight. He also noted the shareholders had spent £60,000 for no return. The company had spent most of its English money in two and a half years under Smith's management without being able to start production. It seems the directors lost patience, and a new English manager, David Lawson, took over from Smith in November 1875.

David Smith was still a major shareholder and continued to argue for the Berrima branch line as late as April 1877, as it was needed for cheaper coal.

Iron Production (1876 – March 1877)

In January 1876, Lawson was getting the blast furnace ready. It started smelting iron on February 5, 1876. Thanks to Levick's earlier changes (especially the second 'stove') and the closed-top conversion finished by Smith, the blast furnace produced about 100 tons of pig-iron per week from the start, and soon reached 120 tons per week.

The blast furnace used coke made from Bulli coal. The quality of coke is very important for blast furnaces, and Bulli coal was excellent for coking. There were no coke ovens at the factory. The coal was coked by setting it on fire in open piles on the hilltop near the furnace, covered by ashes from earlier batches. This was a wasteful process because the valuable coke oven gas couldn't be used as fuel.

There was no railway to Bulli. So, the coal was shipped from the Bulli Jetty to Sydney. There, it was transferred to railway wagons and sent to Mittagong. The same coal seams as Bulli passed under Mittagong, but they were over 600 feet deep. These seams were also exposed in the Wingecaribee River gorge near Berrima, where Smith had started a mine. Smith and others had pushed for a short railway line from the Berrima mine to the main railway line in 1874 and 1875. The first Berrima railway line was built and privately funded, but not until 1881, long after the iron works closed. In 1876–1877, this meant the factory relied on very expensive coal from Bulli or Bowenfels. Although the Berrima mine eventually opened in 1881, the closure of the iron works meant it lost a big local customer. The mine later closed in 1889.

In April 1876, the factory had to shut down due to a water shortage. The works needed a lot of water for cooling and to make steam.

The company advertised its pig-iron in June 1876, with letters from Sydney foundries praising its quality. In September 1876, the factory was making iron, but the rolling mills weren't working. This was again due to poor foundations, and they would be expensive to fix. The mills were also not powerful enough to roll large rails. Lawson had the rolling mills rebuilt in November 1876 and hired experienced rollers from England. But by the time the works closed in March 1877, the mills had only produced 52 tons of iron bars.

The factory needed to make higher-priced finished iron products (like bars, plates, or rails) to be profitable. Selling ordinary pig-iron was not profitable because imported pig-iron had become cheap. Around this time, other local iron producers started to appear. By 1876, pig-iron was being made at Lithgow in New South Wales, Lal Lal in Victoria, and in Tasmania.

In 1876, New South Wales produced 2,679 tons of pig-iron, worth £13,399. Most of this came from the Fitzroy Iron Works. However, the small, old-fashioned factory couldn't compete with imported iron. Iron smelting stopped on March 16, 1877. The blast furnace had produced 3,273 tons in the previous nine months, but it never made pig-iron again. There was a pile of unsold pig-iron left when the factory closed.

Larkin, Hunter, and Henshaw (1877–1878)

Three partners, Larkin, Hunter, and Henshaw, bought the unsold pig-iron and leased the factory in late 1877. They processed the leftover pig-iron and rolled it into bars. Hunter and Henshaw left in January 1878. Edward G. Larkin continued the business until he finished a contract to supply the Joadja oil shale mine with 50 tons of light wrought-iron rails for a tramway. After this, 106 tons of Fitzroy iron were sent to the Eskbank Ironworks at Lithgow. This was the last iron smelted and processed at the Fitzroy works.

Larkin and Jeavons (1879-1880)

Edward Larkin was the first to mine the Mittagong iron ore (limonite) for purifying town gas in 1879.

Larkin then worked with David Jeavons (from a famous English company) to try and make steel at the Fitzroy works. These experiments, using hydrogen gas, ended tragically on October 5, 1880, when a gas explosion killed Jeavons instantly and injured Larkin. It was reported that Jeavons had paid for the experiments himself and was very close to success. His death left a newly married wife.

Larkin continued to be involved with the now-closed works. He later worked for William Sandford and the Mittagong Land Company.

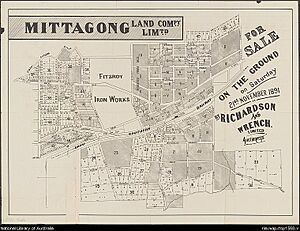

Mittagong Land Company and Final Years (1883–1910)

The 1,600-acre landholding, including the old factory, was sold to a new company, The Mittagong Land Company, in 1883 for £27,100. This also included 40 acres of the limestone quarry at Marulan. The new company kept the iron works intact but focused on selling the land. The first land sale happened in 1884.

While working for the Mittagong Land Company in 1884, Edward Larkin improved the recreational area at the Chalybeate Spring, which was on the company's land. He added a pipe to make it easier for visitors to get the water.

The company looked for coal on the property, hoping that if coal was found, others might be interested in taking over the iron mine and works. In 1887, they found a 14-foot thick seam of good coking coal at a depth of 657 feet by drilling. However, an attempt to dig a shaft to these seams failed in 1893 due to water. So, the long-sought coking coal was there, but they couldn't mine it.

The company also dug some shafts into the iron ore in 1888, probably to see how big the deposit was.

Various groups leased the works from the Mittagong Land Company or experimented with iron-making at Mittagong between 1886 and 1910.

William Sandford (1886–1887)

William Sandford leased the iron works in March 1886. He planned to re-roll old iron rails for a contract with the New South Wales Government, which he shared with the Eskbank Iron Works at Lithgow.

Sandford hired Enoch Hughes as his manager for the first four months, and Larkin as his engineer. Production started in August 1886. Around September 1886, he also made galvanised iron sheets.

Sandford might have thought about restarting the blast furnace. He bought a blowing cylinder from the old blast furnace at the Eskbank Ironworks in October 1886, but he never installed it.

The rolling mill at Mittagong was not powerful enough to roll the heavy rails needed for the contract. After nine months, Sandford moved the work to the Eskbank Ironworks. This was the end of production at the Fitzroy Iron Works. No more iron products were ever made there after 1887.

Sandford was more successful at Lithgow, at least at first. He is seen as the founder of Australia's modern iron and steel industry.

Brazenall and Son (1889)

William Brazenall was a blacksmith who came to Mittagong in 1873 with the company. He later set up his own blacksmith shop. In 1889, he and his son, William Brazenall, Junior, experimented with making iron pipes from Mittagong iron ore. They were helped by Joseph Rowley, who had blast furnace experience. Working from their small shop near the old works, they were interested only in the iron ore, not restarting the Fitzroy Iron Works. They smelted the ore in a small blast furnace they built themselves. They successfully cast a sample pipe, nine feet long and four inches wide, and also made some pig-iron.

Their first experiments used charcoal as fuel. Later, they used the 'anthracite' coal from Mittagong directly in the furnace without coking it.

Plans to start a company to use the ore led to public demonstrations of pipe casting and a public meeting. Samples were shown at the London Mining Exhibition in 1891. But the timing was bad. Australia was entering an economic downturn, and imported pig-iron was duty-free before 1893. The failure to start the company disappointed William Brazenall, Sen., who left Mittagong. He later went bankrupt but continued to invent things.

William Brazenall, Jun., stayed in Mittagong and started a successful foundry business. He made cast-iron lamp posts, verandah posts, and iron lacework for buildings. Some of these still exist today.

End of the Bessemer Company (1893)

In 1893, the Fitzroy Bessemer Steel, Hematite, Iron and Coal Company, which had been inactive for a long time, was officially closed. By then, its shares were worthless.

Alfred Lambert and 'Lambert Brothers' (1896)

In 1896, a company called 'Lambert Brothers' (claiming to be linked to a famous English firm) came to New South Wales. They were interested in a large government contract to make 150,000 tons of steel rails locally. Alfred Lambert said he had talked to Sir George Dibbs, the Premier, in London in 1892. Dibbs had encouraged him to set up operations in New South Wales.

Lambert moved to Mittagong in April 1896 and leased the ironworks property for 21 years. It was reported that a railway branch line to the works would be built.

In May 1896, it was confidently predicted that the works would reopen on a scale "never before attempted." Lambert said the works would employ a thousand men by January 1897 and export products worldwide. All this was to be done "without any assistance from the State," fitting the free-trade policy of Premier George Reid's government.

It was strange why a British industrialist wanting to make steel rails would choose an old, unused ironworks. Some people in the area were suspicious, but their concerns were dismissed. Some newspapers questioned Mittagong as a site for a steelworks and doubted if 'Lambert Brothers' could succeed without government protection.

By June 1896, Alfred Lambert had arranged to use the Fitzroy Iron Works. Lambert said he had found more iron ore, was digging for coal, and preparing the site, including cleaning out the old blast furnace. The old blast furnace would be used to smelt pig-iron and melt down old equipment for the new machinery. Smoke was seen from the chimneys by mid-June, and workers got their first pay on June 13, 1896. However, work suddenly stopped on July 1, 1896. Lambert wrote to the Minister of Works, complaining about the rail contract conditions and effectively withdrawing. 'Lambert Brothers' never restarted work at the Fitzroy Iron Works.

The closure was sudden. Money, or the lack of it, was again a problem. On September 1, 1896, Alfred Lambert was sent to Berrima gaol for not paying wages. He owed money from the Fitzroy Iron Works. He was given eleven weeks in jail. A cheque he wrote in July 1896 bounced, leading to a charge of getting money by false pretenses. He couldn't pay his debts and soon went bankrupt.

His bankruptcy hearing began on November 19, 1896, after he was released from Berrima Gaol. Lambert gave strange and unbelievable evidence about his background and wealth. He claimed to be backed by very rich people who had died. He also admitted there was no company called 'Lambert Brothers'. This suggested he was a confidence-artist. He had tricked the government, the local press, his unpaid employees, and creditors. He avoided further punishment after his acquittal.

Daniel Flood (1904–1910)

In the very last attempt to restart the works, a Sydney company, 'Flood and Co.', bought the machinery and buildings in 1904. They hoped to form a company to restart the works before taking them apart. Daniel Flood, the man behind this, seemed to be a difficult person. Old equipment was being removed in November 1904, and Flood was seriously injured during the demolition.

Reports said new equipment was set up by August 1910. They expected to make pig iron using a "new process" and do other foundry work. Flood said his "patent" was a success and he was waiting for more new equipment to arrive in December 1910 to start production. But these plans never happened. Meanwhile, Australia's first modern blast furnace had started working at Lithgow in May 1907.

After the Iron Works

From about 1879 and into the 1900s, iron ore (limonite) was dug up at Mittagong. It was used to remove hydrogen sulphide in the process of making town gas. In February 1920, Michael Cosgrove got a license to look for iron and coal on 22 acres of land owned by the Mittagong Land Company. He planned to work the old iron mine again, probably for gas purification.

The blast furnace structure was taken down in 1922 (some sources say 1927). The buildings around it were gone by 1913.

The Mittagong Land Company officially closed down in 1924, ending the long story of the Fitzroy Iron Works and its many owners.

In 1941, iron ore was briefly mined again at Mittagong for iron-making, but this time it was for the Port Kembla steelworks.

Finding Old Remains

The location of the blast furnace was always known, but people didn't know that other parts of the iron works still existed.

During digging for a new Woolworths store in 2004, the remains of the Iron Works were found.

The site was carefully dug up and studied. The new building project was changed to include these historic items. You can now see the displays in the underground car park. Two stone rolls from the Chilean mill, used to grind clay, are also on display.

Legacy and What's Left

The Fitzroy Iron Works helped the town of Mittagong grow, especially the area once called 'New Sheffield'. Building plots in 'New Sheffield' were sold by the company in 1865 to raise money. The name of Bessemer Street in this area reminds us of Mittagong's iron-making past. So do Ironmines Oval and Iron Mines Creek, which are between the old iron works and the blast furnace sites. Lake Alexandra, a man-made lake, was also built by the Fitzroy Iron Works. More building plots were sold when the Mittagong Land Company owned the land.

The lion is the symbol of Mittagong and its public school. Some of Mittagong's sports teams are called the Mittagong Lions and use the lion as their symbol. The specific lion design they use, known as the 'Fitzroy lion', is very similar to the commemorative doorstops made at the Fitzroy Iron Works in 1850.

At the site of the old blast furnace, you can see a drain and the foundations for the blast machinery, both cut into the solid sandstone. Nothing remains of the furnace structure itself.

Also at the blast furnace site are four rough pieces of rusty iron. These are almost certainly parts of a 'bosh skull' from the old furnace. Two of these pieces have large bits of coal inside them. This might be from when they tried to smelt iron using poor-quality local coal instead of coke.

The delicate roof trusses of the Uniting Church in Albert Street, Mittagong (originally the Methodist Church), are made of iron from the Fitzroy Iron Works. The foundation stone was laid by the company's chairman on May 24, 1865.

The cast-iron cylindrical casings used in the supporting columns of the Prince Alfred Bridge over the Murrumbidgee River at Gundagai were made in the Fitzroy Iron Works foundry from iron smelted there. The bridge, opened in 1867, still stands and carries local traffic, though it's no longer part of the Hume Highway.

The cast-iron cylindrical casings for the supporting columns of the Denison Bridge across the Macquarie River at Bathurst (built 1869–1870) were cast at P. N. Russell & Co.'s foundry in Sydney. They mainly used pig-iron from the Fitzroy Iron Works, which was found to be stronger than imported iron. The Denison Bridge still stands but is now only used by pedestrians.

The Fitzroy Iron Works itself didn't make a profit, but it helped lay the groundwork for Australia's later successful iron and steel industry.

The blast furnace built at the Fitzroy Iron Works in 1863–64 was the first blast furnace in Australia. Enoch Hughes, who oversaw its construction, later worked at the Lithgow Valley Iron Works (Eskbank Ironworks) at Lithgow. In 1875, he built another blast furnace at Lithgow, which operated until 1882. During his second time at Mittagong in 1868, the Fitzroy Iron Works rolling mills produced the first iron plate rolled in Australia. Hughes also claimed to have rolled the first iron rails there. After Hughes, Thomas Bladen worked at Fitzroy and later became a government inspector at Eskbank Ironworks, where he had disagreements with Hughes.

William Sandford leased the Fitzroy Iron Works to roll iron rails in 1886. After nine months, in 1887, he moved his operations to the Eskbank Ironworks at Lithgow. He owned the Eskbank Ironworks in 1901 when it first made steel and when its new blast furnace (the first truly modern one in Australia) started in May 1907. Sandford is rightly seen as the founder of the iron and steel industry in Australia. A later owner of the Lithgow works moved the operations to Port Kembla between 1928 and 1931, where steel is still made today.

Hughes, Bladen, and Sandford were just some of the people who worked at Fitzroy and later went to Eskbank Ironworks. This shows a clear connection from the early efforts at Fitzroy Iron Works, through Eskbank Ironworks, to Port Kembla and Australia's modern iron and steel industry.

In the late 1800s, there was a push for federation of the Australian colonies. This would remove taxes between colonies and protect local industries. From January 1, 1893, the New South Wales government put a tax of 10 shillings per ton on imported pig-iron. No significant amount of pig-iron had been smelted from ore in New South Wales since 1882, so this tax encouraged local production. The New South Wales iron and steel industry benefited from politicians who supported protection, like George Dibbs, William Lyne, and John See, especially as the cost of locally rolled iron became cheaper than imports for some wrought iron products. New South Wales joined the new Commonwealth of Australia as the only state with a large iron and steel industry, and it remained so for the first four decades of the 1900s.

The change in government policy to protect industry came too late to help the Fitzroy Iron Works. But Fitzroy had already proven that good quality iron could be made from local ore. The lessons learned at Fitzroy influenced later decisions to build iron and steel works close to coking coal deposits and good transport. Marulan, the same source of limestone used by Fitzroy, has been used by the Port Kembla steelworks since 1928.

The Fitzroy Iron Works is remembered by a monument built in 1948 at the blast furnace site. The remains found in 2004 also have signs explaining their history.

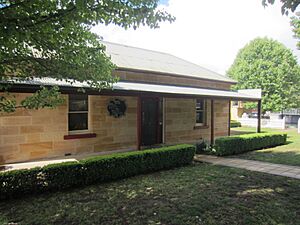

The only complete building left from the iron works is 'Ironstone Cottage'. This sandstone cottage on the Old Hume Highway was once used by the iron works managers.

Images for kids

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |