Franklin J. Moses Jr. facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

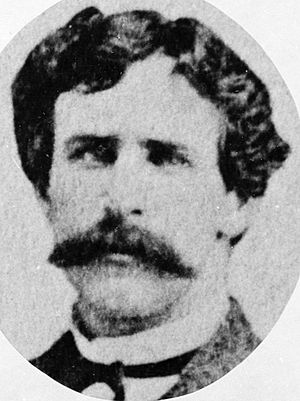

Franklin Moses

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| 75th Governor of South Carolina | |

| In office December 7, 1872 – December 1, 1874 |

|

| Lieutenant | Richard Howell Gleaves |

| Preceded by | Robert Kingston Scott |

| Succeeded by | Daniel Henry Chamberlain |

| 27th Speaker of the South Carolina House of Representatives | |

| In office November 24, 1868 – November 26, 1872 |

|

| Governor | Robert Kingston Scott |

| Preceded by | Charles Henry Simonton |

| Succeeded by | Samuel Lee |

| Adjutant-General of South Carolina | |

| In office July 6, 1868 – December 7, 1872 |

|

| Governor | Robert Kingston Scott |

| Preceded by | Albert Garlington |

| Succeeded by | Henry Purvis |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1838 Sumter District, South Carolina, U.S. |

| Died | (aged 67–68) Winthrop, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse | Emma Buford Richardson (1869–1878) |

| Children | 4 |

| Education | University of South Carolina |

Franklin Israel Moses Jr. (1838–December 11, 1906) was a South Carolina lawyer and editor. He became an important Republican politician in South Carolina during the Reconstruction Era. This was the time after the American Civil War when the Southern states were rebuilt.

Moses was elected to the state legislature in 1868. He then became governor in 1872, serving until 1874. Some people called him the 'Robber Governor' because of how he spent state money.

Before the Civil War, Moses supported the idea of states leaving the Union. After the war, he was willing to work with different groups. As speaker of the House, he supported making the state university open to all races. He also helped create new social programs and pensions for older people. He even started a Black militia to protect freedmen (formerly enslaved people) from white groups. He was also known for inviting African Americans to social events.

When Moses was young, his middle initial was often mistaken for "J." So, he became known as Franklin J. Moses Jr. His father, Franklin J. Moses Sr., was also a lawyer. He served as a state senator for over 20 years. Later, he became a judge and then the Chief Justice of the State Supreme Court.

Contents

Early Life and Family Background

Franklin Moses Jr. was born in 1838 in Sumter District, South Carolina. His parents were attorney Franklin J. Moses Sr. and Jane McLellan. His father came from a well-known Jewish family in Charleston. His mother was Methodist and of Scots-Irish background.

Moses Jr. was raised as an Episcopalian and was not connected to Judaism. However, many people thought he was Jewish because Southerners often focused on the father's family background. His political rivals tried to use this idea against him. He attended South Carolina College (now the University of South Carolina) in 1855. He left the college the same year.

After studying law, Moses became a lawyer in South Carolina. In 1860, he became the private secretary for Governor Francis Wilkinson Pickens. Governor Pickens supported the idea of states leaving the Union. When the Civil War began, Moses became a Colonel in the Confederate Army. He helped sign up soldiers for the Confederate army. Moses claimed he was the one who took down the United States flag from Fort Sumter in 1861.

Political Career and Public Service

In 1868, during the Reconstruction period, Moses was elected to a statewide office. He became the Adjutant and Inspector General as a Republican. He was also elected to the South Carolina House of Representatives from Charleston. He quickly became the speaker of the House. His father was elected Chief Justice of the State Supreme Court in the same year.

Protecting Voters and Public Safety

As Speaker of the House, Moses created a statewide militia. This group had about 14,000 men, mostly freedmen, led by white officers. He used this militia to protect Black voters. This was important because groups like the Ku Klux Klan used threats and violence before the 1870 elections. Moses also tried to stop Democratic Party meetings and voters. During this time, election results often depended on who had more armed force.

Opening Doors at the University of South Carolina

In 1869, the legislature made Moses a trustee for the University of South Carolina. He wanted to make the state university open to all races. Many white people were against this idea. Other trustees appointed that year included Francis L. Cardozo and Benjamin A. Boseman. They were the first men of color on the University Board of Trustees.

Moses encouraged Black students to apply. The college even started a special program to help Black students catch up. This was because they had not been allowed to get a formal education before. In 1873, Henry E. Hayne, the Republican secretary of state, became the first Black student admitted. This was a big event, and national newspapers like The New York Times wrote about it. Some professors resigned because they did not like this change. Moses then hired new teachers.

After Democrats took control of the state government in 1876, they closed the college. In 1877, a new law was passed that only allowed white students. The college reopened in 1880 as a white-only college. Claflin College in Orangeburg was set up for students of color. Black students were not admitted to the main state university again until 1963. This was years after the US Supreme Court said that segregated public schools were illegal in Brown v. Board of Education.

Supporting Social Programs

Moses also supported social programs and the idea of public money for old-age pensions. He organized the state militia, which was mostly made up of Black men. This militia helped protect freedmen when white groups tried to bring back white supremacy.

Moses was reelected to the House in 1870 and stayed as speaker. White Democrats accused the legislature of being very corrupt. However, the government was also spending money on important things like railroads and public services. These things had been ignored by the wealthy landowners before the war. The state's debt increased from about $5.4 million in 1868 to $18.3 million by 1872. Historians like W.E.B. Du Bois noted that this debt increase was partly because states were investing in public projects. Before the war, education was private, and there were few hospitals or railroads.

Becoming Governor

When Republicans chose Moses as their candidate for governor, some people in his own party tried to stop him. But with strong support from Black Republicans, Moses was elected in 1872. He became the 75th governor of South Carolina.

As governor, Moses was known for spending a lot of state money. He spent $40,000 to buy the Preston mansion as the official governor's home. During his two years as governor, he spent $40,000 on living expenses, including official parties. Many white Democrats were upset because he invited Black colleagues and politicians to the mansion.

In 1874, some allies of Wade Hampton III tried to charge Governor Moses with misusing state money. Hampton was a Democrat who would later become governor in 1876. Moses ordered the militia in Columbia to stop his arrest. The court decided that Moses could not be charged while he was governor. He could only be removed through impeachment by the state legislature.

Historians today recognize Moses for his important work in civil rights for African Americans. He is seen as someone who helped build alliances between African Americans and Jewish people in the future. He chose to work with the newly freed Black citizens to create a new society.

Later Life and Challenges

After leaving office in 1874, the General Assembly chose Moses for a seat on the circuit court. However, Republican Governor Chamberlain blocked his appointment. Many in his own party opposed it because of his reputation for spending state money.

In 1876, the Democrats took back control of state politics. Wade Hampton III was elected governor. He won by a small number of votes, even with reports of widespread fraud. For example, some counties counted more votes for Hampton than they had registered voters. When federal troops left the state in 1877, the Reconstruction era ended.

Moses faced difficulties in his later life. He left South Carolina. He later settled in Winthrop, Massachusetts. There, he became the editor of a local newspaper and led town meetings. He continued to face legal issues. He died on December 11, 1906, and was buried in Winthrop.

Personal Life

Franklin Moses Jr. married Emma Buford Richardson (1841–1920) on December 20, 1869. She was not Jewish, similar to his father's marriage. They had four children together: Franklin J. III (born 1860), Mary Richardson (born 1862), Jeannie McLellan (born 1867), and Emma Buford Moses (born 1872). Before his political career, from 1866 to 1867, Moses was the editor of the Sumter News newspaper.