François Rabelais facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

François Rabelais

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | between 1483 and 1494 Chinon, Touraine, France |

| Died | prior to 14 March 1553 (aged between 61 and 70) Paris, France |

| Occupation | Writer, physician, humanist, clergyman |

| Alma mater |

|

| Literary movement | Renaissance humanism |

| Notable works | Gargantua and Pantagruel |

François Rabelais (born between 1483 and 1494; died 1553) was a famous French writer, doctor, and scholar during the Renaissance period. He is best known for his funny and often silly stories, especially those about giants. His books often made fun of things and used lots of jokes.

Rabelais was a complex person. He was a monk but also questioned some church ideas. He was a doctor but also loved to have fun. He lived during a time of big changes, like the Reformation, and he wrote about the important ideas of his era in his novels.

He looked up to another famous scholar named Erasmus. Rabelais believed in Renaissance humanism, which meant he valued learning from ancient Greece and Rome. He often criticized the old ways of thinking and the powerful leaders of his time. His funny stories were so popular that the word Rabelaisian is still used today to describe something with "big, funny humor" or "wild imagination."

Contents

Biography

We don't know the exact place or date of François Rabelais's birth. He was likely born in November 1494 near Chinon, France. His father was a lawyer. Today, there's a museum about Rabelais at La Devinière in Seuilly, which some believe was his birthplace.

Rabelais first joined the Franciscan monks. Later, he went to Fontenay-le-Comte where he studied Greek and Latin, as well as science and law. He became known and respected by other smart people of his time. The Franciscan order didn't allow the study of Greek, which frustrated Rabelais. So, he got permission from Pope Clement VII to leave the Franciscans and join the Benedictine Order.

After some time, he left the monastery to study medicine at the University of Poitiers and the University of Montpellier. In 1532, he moved to Lyon, a major center for learning during the Renaissance. He started working as a doctor at the Hôtel-Dieu de Lyon hospital.

While in Lyon, Rabelais also helped a printer named Sebastian Gryphius. He wrote a letter to Erasmus and helped publish medical texts. In his free time, he wrote and published funny stories. These stories often criticized the rules and ideas of the time, especially about education and monasteries.

In 1532, Rabelais published his first book, Pantagruel King of the Dipsodes. He used the fake name Alcofribas Nasier, which was an anagram of his own name. He got the idea for giants from popular stories sold at fairs. His books were about a fun-loving way of life, which made them popular. However, church leaders didn't like them. This first book introduced new words into French, like encyclopédie and utopie. Even though his books were popular, the Sorbonne (a famous university in Paris) and other church officials banned them in 1543 and 1545.

Rabelais taught medicine in Montpellier in 1534 and 1539. In 1537, he even gave an anatomy lesson using the body of a hanged man.

Rabelais often traveled to Rome with his friend and patient, Cardinal Jean du Bellay. He also lived in Turin for a short time. Rabelais sometimes had to hide because he was in danger of being accused of heresy (having beliefs against the church). Only the protection of du Bellay saved him after his novel was banned by the Sorbonne.

Between 1545 and 1547, Rabelais lived in Metz to avoid problems with the University of Paris. In 1547, he became a priest in two different places near Paris.

With help from the powerful du Bellay family, Rabelais got permission from King Francis I to keep publishing his books. But after the king died in 1547, many important scholars didn't like Rabelais's work. The French Parliament stopped the sale of his fourth book, published in 1552.

Rabelais stopped being a priest in January 1553 and died in Paris later that year.

Novels

Gargantua and Pantagruel

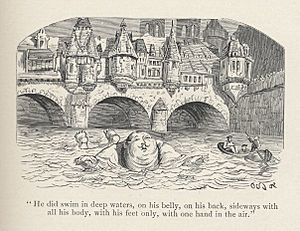

Gargantua and Pantagruel tells the exciting and funny adventures of a giant named Gargantua and his son, Pantagruel. The stories are full of learning, celebrations, and silly moments. The first book was Pantagruel: King of the Dipsodes. In the first chapter, Pantagruel's family tree goes back 60 generations to a giant named Chalbroth. The narrator even jokes that a giant named Hurtaly rode Noah's Ark like a toy!

Most chapters are humorous and wild, but some serious parts share Rabelais's ideas about education. For example, the chapters about Gargantua's childhood and his father's letter to Pantagruel show a detailed vision of how children should be taught.

Thélème

In the second novel, Gargantua, the giant builds a special place called the Abbey of Thélème. This abbey is very different from normal monasteries. It's open to both men and women, has a swimming pool, and no clocks! Only good-looking people are allowed to enter. The rules at the gate say who is not welcome, like hypocrites or mean judges.

The people in the Abbey of Thélème live by one simple rule: DO WHAT YOU WANT

- Fay ce que vouldras

The Third Book

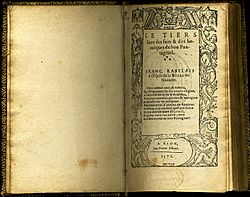

The Third Book was published in 1546. Like his earlier books, it was banned by the Sorbonne. In this book, Rabelais discussed ideas he had explored before, like the "woman question" (debates about women's roles).

This book has much more talking between the characters than action. The main question is whether Panurge should get married. Panurge asks many different people for advice, including wise people, friends, and even a jester. The story is funny because Pantagruel and Panurge often disagree on what the advice means. Panurge is very stubborn and only wants to hear what he wants to hear. Pantagruel, on the other hand, becomes wiser in this book.

At the end of The Third Book, the characters decide to sail off to find the Oracle of the Divine Bottle. The last chapters talk a lot about "Pantagruelion" (hemp), a plant used for ropes and medicine in the 1500s. The narrator describes the plant in great detail and praises its many uses.

The Fourth Book

A first version of The Fourth Book came out in 1548. This book was about a journey, inspired by ancient Greek myths and the voyages of explorers like Jacques Cartier to Canada. It included some of the most famous parts of Rabelais's work, like a big storm at sea and Panurge's sheep.

Use of Language

The French Renaissance was a time when the French language was changing and developing. The first French grammar book was published in 1530, and the first dictionary came out nine years later. Spelling was not set in stone yet. Rabelais liked to spell words in a way that showed where they came from.

Rabelais used words from Latin, Greek, and different French regions. He also made up new words and used puns, funny creatures, and silly songs. Many words and phrases from Rabelais are still used in modern French. Some of his words even made their way into English through translations of his work.

Scholarly views

Most experts today agree that Rabelais wrote from a viewpoint of Christian humanism. This means he valued classical learning and believed the church needed to be reformed to be more like its original, simple form. Rabelais criticized what he saw as fake Christian ideas from both Catholics and Protestants. Because of this, he was attacked by both sides and sometimes called a threat to religion. For example, Catholic leaders asked for all four of his books to be banned. On the other hand, John Calvin, a Protestant leader, thought Rabelais didn't go far enough in his criticisms.

Experts have debated Rabelais's work for a long time. Some saw him as a humanist, while others focused on the funny, rebellious side of his humor. Today, some discussions also look at whether Rabelais was fair to women in his stories.

In literature

Many famous writers have been influenced by Rabelais:

- In his novel Tristram Shandy, Laurence Sterne often quoted Rabelais.

- James Joyce mentioned "Master Francois somebody" in his 1922 novel Ulysses.

- Mikhail Bakhtin, a Russian thinker, developed his ideas about "carnival" and "grotesque body" from Rabelais's world. He saw Rabelais's humor as a way for people to express themselves together.

- Aldous Huxley admired Rabelais's work, saying he "accepted reality in its entirety."

- George Orwell, however, was not a fan, calling him "an exceptionally perverse, morbid writer."

- Milan Kundera, a famous novelist, said that Rabelais, along with Cervantes, was a founder of the art of the novel.

- Rabelais is seen as a very important writer in Kenzaburō Ōe's 1994 Nobel Prize in Literature speech.

- In the musical The Music Man, Rabelais's name is mentioned as evidence that the town librarian has "dirty books."

Honours, tributes and legacy

- The public university in Tours, France is named Université François Rabelais after him.

- Honoré de Balzac, another famous French writer, was inspired by Rabelais and quoted him often in his own novels.

- At the University of Montpellier's Faculty of Medicine, new doctors take an oath under Rabelais's robe.

- An asteroid (a small rocky body in space) was named '5666 Rabelais' in his honor in 1982.

- In 2008, J. M. G. Le Clézio called Rabelais "the greatest writer in the French language" in his Nobel Prize speech.

- In France, when a waiter brings the bill at a restaurant, it's sometimes called le quart d'heure de Rabelais (The fifteen minutes of Rabelais). This is a funny saying from a story about Rabelais tricking someone to avoid paying a bill.

Works

- Gargantua and Pantagruel, a series of books including:

- Pantagruel (1532)

- La vie très horrifique du grand Gargantua, usually called Gargantua (1534)

- Le Tiers Livre ("The third book", 1546)

- Le Quart Livre ("The fourth book", 1552)

- Le Cinquième Livre (a fifth book, but it's not certain if Rabelais wrote it)

See also

In Spanish: François Rabelais para niños

In Spanish: François Rabelais para niños

- Rabelais and His World

- Thomas Urquhart

- Peter Anthony Motteux

- The Great Mare

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |