Frederick Barbarossa facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Frederick Barbarossa |

|

|---|---|

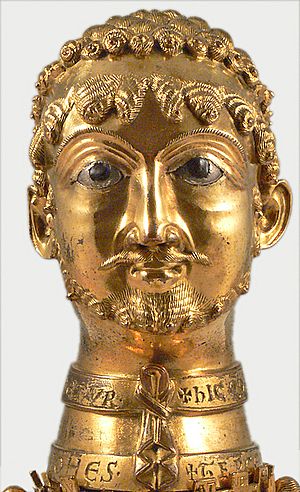

A golden bust of Frederick, given to his godfather Count Otto of Cappenberg in 1171. It was used as a reliquary in Cappenberg Abbey and is said in the deed of the gift to have been made "in the likeness of the emperor".

|

|

| Holy Roman Emperor | |

| Reign | 1155 – 10 June 1190 |

| Coronation | 18 June 1155, Rome |

| Predecessor | Lothair III |

| Successor | Henry VI |

| King of Italy | |

| Reign | 1155 – 10 June 1190 |

| Coronation | 24 April 1155, Pavia |

| Predecessor | Conrad III |

| Successor | Henry VI |

| King of Germany | |

| Reign | 4 March 1152 – 10 June 1190 |

| Coronation | 9 March 1152, Aachen |

| Predecessor | Conrad III |

| Successor | Henry VI |

| King of Burgundy | |

| Reign | 1152 – 10 June 1190 |

| Coronation | 30 June 1178, Arles |

| Duke of Swabia | |

| Reign | 6 April 1147 – 4 March 1152 |

| Predecessor | Frederick II |

| Successor | Frederick IV |

| Born | Mid-December 1122 Haguenau, Duchy of Swabia, Kingdom of Germany (modern-day France) |

| Died | 10 June 1190 (aged 67) Saleph River, Cilician Armenia (modern-day Göksu River, Silifke, Turkey) |

| Burial | |

| Spouse |

Adelheid of Vohburg

(m. 1147; annulled 1153) |

| Issue more... |

|

| House | Hohenstaufen |

| Father | Frederick II, Duke of Swabia |

| Mother | Judith of Bavaria |

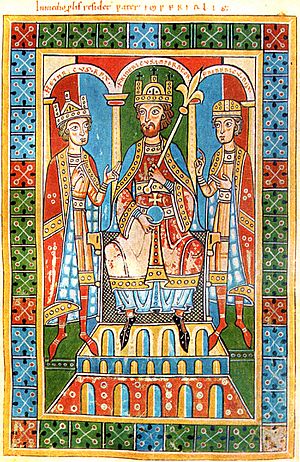

Frederick Barbarossa (born December 1122 – died 10 June 1190), also known as Frederick I, was a powerful Holy Roman Emperor. He ruled for 35 years, from 1155 until his death. He was first elected King of Germany in 1152 and later crowned King of Italy and then Emperor in Rome.

People called him "Barbarossa," which means "red beard" in Italian. In German, he was known as Kaiser Rotbart, meaning "Emperor Redbeard." This nickname stuck because his campaigns in Italy were a big part of his life.

Frederick came from two important German families: the Hohenstaufen (his father's side) and the Welf (his mother's side). This made him a good choice for the throne. He joined the Third Crusade and traveled by land to the Holy Land. Sadly, he drowned in the Saleph river in 1190, and many of his soldiers left the Crusade after his death.

Historians see Frederick as one of the greatest medieval emperors of the Holy Roman Empire. He was known for his long rule, big goals, great organizing skills, and smart decisions in battle and politics. He helped bring back Roman law, which balanced the power of the Pope in German states.

Because he was so famous, Frederick became a political symbol for many groups later on, like the German Empire and even the National Socialist (Nazi) movement. Today, historians try to understand the real Frederick, beyond the legends.

Contents

Frederick's Early Life and Adventures

Growing Up and Learning

Frederick was born in December 1122 in Haguenau. His parents were Frederick II, Duke of Swabia and Judith of Bavaria. He learned important skills like riding, hunting, and using weapons. However, he could not read or write, and he didn't speak Latin. As a young man, he attended important meetings called Hoftage with his uncle, King Conrad III of Germany.

Joining the Second Crusade

In 1147, Frederick joined the Second Crusade. His uncle, King Conrad III, had promised to go on the Crusade. Frederick's father was against his son going, as he was dying and wanted Frederick to care for his family.

Before the Crusade, Frederick married Adelaide of Vohburg. After his father died in April, Frederick became the Duke of Swabia. The German crusader army left Germany seven weeks later.

While traveling through the Byzantine Empire, some crusaders were attacked. Frederick was ordered to get revenge. He destroyed a monastery and punished the attackers.

Frederick and a few others were lucky to survive a flash flood that hit the main army's camp. They had camped on a hill, away from the main group.

The army tried to cross Anatolia by land, but it was too hard with constant attacks from the Turks. King Conrad got sick and returned by ship with Frederick. They later sailed to Acre and visited Jerusalem. Frederick was impressed by the Knights Hospitaller. He also took part in a meeting that decided to attack Damascus.

The Siege of Damascus in July 1148 was a quick defeat. Frederick was noted for his bravery in battle. After this, the German army left Acre. On their way home, Frederick was sent ahead to Germany, arriving in April 1149.

Becoming King and Emperor

How Frederick Became King

When King Conrad died in 1152, Frederick was one of the few people with him. They said Conrad chose Frederick to be the next king, even though Conrad had a young son. Frederick worked hard to get the crown. On March 4, 1152, important princes chose him as the new German king in Frankfurt.

He was crowned King of the Romans in Aachen a few days later. Frederick's family, the Hohenstaufens (also called Ghibellines), and his mother's family, the Welfs (also called Guelfs), were the two most powerful families in Germany.

For many years before Frederick, the German king had little real power. The princes chose the king and kept most of the power for themselves. When Frederick became king, he wanted to bring back the strong imperial power that existed under earlier emperors like Charlemagne.

Germany was made up of over 1,600 small states, each with its own ruler. Frederick aimed to unite them. He was a practical leader who worked with the princes by finding common goals. He wanted to restore the old feudal system, where everyone had a clear place in society.

Rise to Power and First Italian Trip

Frederick wanted to make the Empire as strong as it was under Charlemagne and Otto I the Great. He knew he needed to bring order to Germany first before he could control Italy. He made agreements with the nobles and helped settle a civil war in Denmark.

He also ended his marriage to Adelheid of Vohburg because they were distant relatives and had no children. In March 1153, Frederick made a deal with Pope Eugene III. He promised to protect the Pope and help him regain control of Rome, in exchange for being crowned Emperor.

In October 1154, Frederick began his first trip to Italy. He wanted to fight the Normans in Sicily. He quickly faced resistance. He took control of Milan and then successfully attacked Tortona, destroying it. He was crowned King of Italy in Pavia in April 1155.

He then moved towards Rome, where Pope Adrian IV was having trouble with a group led by Arnold of Brescia. Frederick helped the Pope by stopping the rebels. Arnold was captured and executed.

When Frederick met the Pope, there was a small argument about who should hold the Pope's stirrup. Frederick finally agreed, saying it was "for Peter, not for Adrian." On June 18, 1155, Pope Adrian IV crowned Frederick I Holy Roman Emperor in St Peter's Basilica. Romans rioted that day, and Frederick had to stop the uprising, which led to many deaths and injuries.

After this, Frederick had to return to Germany because of the hot Italian summer and his long absence from home. On his way back, he attacked Spoleto and met with ambassadors from the Byzantine Emperor, who gave him many gifts.

Back in Germany, Frederick brought peace to Bavaria. He gave the Duchy of Bavaria to his cousin, Henry the Lion, who was a powerful leader. In return, the previous Duke of Bavaria, Henry II Jasomirgott, was made Duke of Austria. Frederick made these deals to keep peace among the German princes.

On June 9, 1156, Frederick married Beatrice of Burgundy, which added her large lands to his empire. He also created the "Peace of the Land" to punish crimes and settle arguments. He declared himself the only true Roman Emperor, no longer recognizing the Byzantine Emperor in Constantinople.

Challenges and Further Italian Campaigns

Conflicts with the Pope and Italian Cities

Frederick was upset when Pope Adrian IV made a deal with King William I of Sicily, giving him lands Frederick believed were his. Frederick was also annoyed when papal messengers suggested the imperial crown was a gift from the Pope.

In 1158, Frederick began his second trip to Italy, joined by Henry the Lion. This trip led to the capture of Milan and new rules for the cities of northern Italy. It also started a long fight with Pope Alexander III.

When Pope Adrian IV died in 1159, two Popes were chosen: Alexander III and Victor IV. Both wanted Frederick's support. Frederick supported Victor IV, and in response, Alexander III removed both Frederick and Victor IV from the Church (excommunicated them).

Milan rebelled again and even humiliated Frederick's wife, Empress Beatrice. Milan finally surrendered in 1162 and was largely destroyed. Other Italian cities then submitted to Frederick. He returned to Germany to settle disputes among his princes.

In 1164, Frederick took what were believed to be the relics of the "Biblical Magi" (the Wise Men) from Milan and gave them to the Archbishop of Cologne. These relics were very important and attracted many pilgrims.

Frederick supported the antipope Paschal III after Victor IV died. In 1166, Frederick began his fourth Italian campaign. He wanted to secure Paschal III's claim and have his wife Beatrice crowned Empress. Henry the Lion refused to join him this time.

In 1167, Frederick's army won a big victory over the Romans. He had his wife crowned Empress and received a second coronation from Paschal III. However, his campaign was stopped by a sudden disease (like malaria or plague) that hit his army. Frederick had to flee back to Germany, where he stayed for six years. During this time, he settled church issues and improved relations with other European rulers. His eldest son, Henry, was crowned King of the Romans in 1169.

Later Years and Defeats

Anti-German feelings grew in Italy. In 1174, Frederick made his fifth trip to Italy. He faced the Lombard League, a group of northern Italian cities that had joined together against him. These cities had become very rich through trade.

In 1175, the Lombard cities defeated Frederick at Alessandria. This was a big shock. With Henry the Lion refusing to help, Frederick's campaign failed completely. He suffered a major defeat at the Battle of Legnano near Milan on May 29, 1176. He was wounded and thought to be dead for a while.

This battle changed everything for Frederick's claim to power. He had to negotiate for peace with Pope Alexander III and the Lombard League. In the Peace of Anagni (1176) and the Peace of Venice (1177), Frederick recognized Alexander III as the true Pope. He had to humble himself before the Pope, similar to what happened with Pope Gregory VII and Henry IV, Holy Roman Emperor a century earlier. This settled the long-running argument about whether the Emperor could name popes and bishops.

Frederick was formally crowned King of Burgundy in Arles on June 30, 1178, to strengthen his rule after his Italian defeats.

Frederick did not forgive Henry the Lion for not helping him in Italy. By 1180, Henry had built a very powerful state in Germany. Frederick used the anger of other German princes against Henry. In 1180, a court of bishops and princes declared Henry an outlaw and took away his lands. Frederick then invaded Saxony to force Henry to surrender. Henry's allies left him, and he finally gave in to Frederick in November 1181. Henry spent three years in exile before being allowed back to Germany, but with much less power.

Frederick still faced problems in Germany, with constant small wars between states. Italian unity under German rule was still a dream. The Pope remained the most powerful force in Italy.

In 1184, Frederick held a huge celebration called the Diet of Pentecost, where his two oldest sons became knights. Later that year, Frederick went to Italy again. In 1186, he arranged for his son Henry to marry Constance of Sicily, who was next in line to the throne of Sicily. This marriage was against the wishes of Pope Urban III.

The Third Crusade and Frederick's Death

Joining the Crusade

In November 1187, Frederick received letters from the Crusader states in the Near East, asking for help. He agreed to join the Third Crusade. On March 27, 1188, at a big meeting in Mainz, Frederick took the crusader's vow. His second son also joined. His eldest son, Henry VI, stayed in Germany to rule.

Frederick ordered a tax on the Jews of Germany to pay for the Crusade, but he also protected them. He forbade anyone from speaking against Jews and sent his marshal to stop mobs threatening Jews in Mainz. Frederick rode through the streets with a rabbi to show his protection. He successfully prevented the terrible massacres of Jews that had happened during earlier Crusades.

Frederick had signed a peace treaty with Saladin in 1175, so he sent a message to Saladin to end their agreement. He also received promises of supplies and safe travel from Hungary and the Seljuks.

On April 15, 1189, Frederick formally began his Crusade. His army was very well-planned and organized. Modern historians believe his army had about 12,000–15,000 men, including 3,000–4,000 knights.

The Crusaders marched through Hungary, Serbia, and Bulgaria, then entered Byzantine lands. The Byzantine Emperor, Isaac II Angelos, had a secret alliance with Saladin, which complicated things. A Hungarian army of 2,000 men joined Frederick's forces.

The Crusaders continued through Anatolia, winning battles against the Turks. They reached Cilician Armenia. Saladin was worried about Frederick's powerful army and had to send troops to stop them, weakening his forces at the Siege of Acre.

Frederick's Tragic End

On June 10, 1190, Frederick Barbarossa drowned in the Saleph river, near Silifke Castle. He had chosen a shortcut along the river, based on local advice.

Frederick's death caused thousands of German soldiers to leave the Crusade and return home. The remaining German-Hungarian army was hit by disease near Antioch. Only about 5,000 soldiers, a third of the original force, reached Acre. Frederick's son, Frederick VI, continued with the army, hoping to bury his father in Jerusalem.

Frederick's unexpected death left the Crusade without its main leader. The other leaders, Philip II of France and Richard the Lionheart, had traveled by sea. Richard continued fighting Saladin and won some lands along the coast of Palestine. However, he failed to conquer Jerusalem itself before returning home. He signed the Treaty of Ramla, which allowed Jerusalem to remain under Muslim control but let unarmed Christian pilgrims visit the city.

Frederick's Legacy and Legends

Bringing Back Roman Law

The rich trading cities of northern Italy led to a renewed interest in the Justinian Code, an old Roman legal system. Legal experts began using it again. Frederick was the first to use these new lawyers to help him rule his kingdom in a logical way. This legal system also helped him claim his right to rule both Germany and northern Italy.

The Justinian Code helped Frederick see himself as a new Roman emperor. It gave a logical reason for his power and goals, which was different from the Church's claims of authority through divine revelation. The Church often opposed Frederick because of these ideas. Frederick wanted to have a strong role over the Church, like the great emperors of old.

Economic Growth in Germany

Frederick encouraged economic growth and trade in Germany, especially after 1165. His reign saw a big increase in wealth and trade. The number of places where coins were made (mints) grew a lot during his rule. He also gave special rights to merchants from important cities, freeing them from many taxes within the Empire.

A Charismatic Leader

Frederick's uncle, Otto of Freising, wrote a history of his reign called Gesta Friderici I imperatoris. This book shows Frederick as a strong and hopeful leader.

Frederick was a very charismatic leader. For over 25 years, he managed to bring back imperial power in the German states. Even though he faced many powerful enemies and suffered defeats, he often came out on top. When he became king, Germany was divided, and the king had little power. Frederick, through his strength and ability to make peace, changed this.

The Kyffhäuser Legend

Frederick is part of many legends, including the famous Kyffhäuser legend. This story says he is not dead but sleeping with his knights in a cave in the Kyffhäuser mountains in Germany. The legend says that when ravens stop flying around the mountain, he will wake up and make Germany great again. His red beard is said to have grown through the table where he sits. Every now and then, he raises his hand and sends a boy to check if the ravens have stopped flying.

This legend was used later by leaders like Kaiser Wilhelm I, who was seen as a new Frederick. Even Adolf Hitler named his invasion of the Soviet Union "Operation Barbarossa" after him.

Children

Frederick's first marriage to Adelheid of Vohburg did not have any children and was ended.

With his second wife, Beatrice of Burgundy, he had the following children:

- Beatrice (born 1162/1163 – died 1174/1179).

- Frederick V, Duke of Swabia (born 1164 – died 1170).

- Henry VI, Holy Roman Emperor (born 1165 – died 1197).

- Conrad (born 1167 – died 1191), later called Frederick VI, Duke of Swabia.

- Gisela (born 1168 – died 1184).

- Otto I, Count of Burgundy (born 1170 – died 1200).

- Conrad II, Duke of Swabia (born 1172 – died 1196).

- Renaud (born 1173 – died before 1178).

- William (born 1175 – died soon after 1178).

- Philip (born 1177 – died 1208), who became King of Germany in 1198.

- Agnes (born 1179 – died 1184).

- Possibly Clemence, who married Sancho VII of Navarre.

Images for kids

-

The Frederick Barbarossa Memorial, near Silifke in Mersin Province, southern Turkey. The text explains in Turkish and German how Frederick drowned nearby.

-

13th-century stained glass image of Frederick I, Strasbourg Cathedral

See also

In Spanish: Federico I Barbarroja para niños

In Spanish: Federico I Barbarroja para niños

- German monarchs family tree

- Dukes of Swabia family tree

- Operation Barbarossa, the codename of the German invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941, named after the emperor by Hitler.