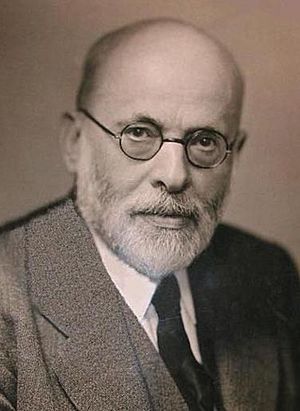

Gaetano Salvemini facts for kids

Gaetano Salvemini (born September 8, 1873 – died September 6, 1957) was an Italian politician, historian, and writer. He was a Socialist and strongly against fascism.

Salvemini came from a humble family but became a well-known historian. He was famous both in Italy and in other countries, especially the United States. He was forced to leave Italy by Benito Mussolini's fascist government.

He first joined the Italian Socialist Party. Later, he followed his own path of humanitarian socialism. He always worked for big political and social changes throughout his life. Salvemini was a key leader for Italian political refugees in the United States. His many writings influenced American leaders during and after the Second World War. His time living outside Italy gave him new ideas. It helped him explain how fascism grew and shaped how people remembered the war and politics in Italy after 1945.

After the war, he suggested a "third way" for Italy. This was a middle path between the Communists and the Christian Democrats.

Contents

Who Was Gaetano Salvemini?

His Early Life and Education

Salvemini was born in Molfetta, a town in Apulia, which is a poor region in southern Italy. He grew up in a large family of farmers and fishermen who didn't have much money. His father, Ilarione Salvemini, was a police officer (a carabiniere) and also taught part-time. His father was a strong supporter of a republic and had even fought with Giuseppe Garibaldi for Italian unification. His mother, Emanuela, was a socialist. His parents' political beliefs and the poverty of his home region shaped his own ideas about politics and society for his whole life.

He went to the University of Florence. There, he met students mostly from northern Italy. He also connected with young socialists who introduced him to Marxism. He later thought about Marxism in his own way. He also learned about the ideas of Carlo Cattaneo and read the socialist journal Critica Sociale by Filippo Turati. It was also in Florence that he met his first wife, Maria Minervini.

After finishing his studies in Florence in 1894, he became a respected historian. His historical studies focused on medieval Florence, the French Revolution, and Giuseppe Mazzini. In 1897, he married Maria Minervini. She was the daughter of an engineer from Apulia. They had five children together: Filippo, Leonida, Corrado, Ugo, and Elena.

A Life-Changing Event

In 1901, after teaching in high schools for several years, he became a professor. He taught medieval and modern history at the University of Messina. While he was in Messina, a terrible earthquake happened in 1908. He lost his wife, all five of his children, and his sister in the 1908 Messina earthquake. He saw it all happen while he was hiding under a window frame. This experience deeply affected his life. He wrote, "I am a miserable wretch, without home or hearth, who has seen the happiness of eleven years destroyed in two minutes."

After this tragedy, he went on to teach history at the University of Pisa. In 1916, he became a Professor of Modern History at the University of Florence. Over the years, he worked with the economist Luigi Einaudi. He developed a practical way of thinking and analyzing things, which he called concretismo. This idea combined values from the Enlightenment, liberalism, and socialism. It was different from the more philosophical ideas of thinkers like Benedetto Croce and Antonio Gramsci.

His Involvement in Politics

Joining the Socialist Movement

Salvemini became more and more interested in Italian politics. He joined the Italian Socialist Party (PSI). In 1910, he wrote an article in the socialist newspaper Avanti! called 'The Minister of the Underworld'. In this article, he strongly criticized the political system of the liberal Prime Minister Giovanni Giolitti. Giolitti was a very powerful figure in Italian politics in the early 1900s. Salvemini accused Giolitti of using the poverty of Southern Italy for his own political gain. He said Giolitti made deals with corrupt politicians who had ties to criminals. Salvemini believed Giolitti used "the miserable conditions of the Mezzogiorno (Southern Italy) to control many southern politicians."

Salvemini was against Italy's expensive military campaign in Libya during the Italo-Turkish War (1911–1912). He felt that this war did not help Italy's real needs. He thought the country needed big economic and social reforms instead. He saw the war as a dangerous mix of unrealistic nationalism and business interests. In 1911, Salvemini left the PSI. He felt the party was silent and didn't care enough about the war. He then started his own weekly political magazine called L'Unità. This magazine became the voice for democratic activists in Italy for the next ten years. He criticized the government's plans for an empire in Africa, calling them foolish.

World War I and Beyond

However, Salvemini supported Italy joining the First World War on the side of the Entente. He believed this would help ordinary people gain more political, economic, and social power in the nation. He also thought it would help achieve national self-determination for different groups. He became a leader of the "democratic interventionists" with Leonida Bissolati. He believed that by fighting for democracy abroad, Italy would remember its own democratic values. He even volunteered to fight in the first two years of the war. In 1916, he married Fernande Dauriac.

As a member of the PSI, he fought for universal suffrage, meaning everyone should have the right to vote. He also worked for the moral and economic improvement of Italy's Mezzogiorno (Southern Italy). He was against corruption in politics. As a meridionalist (someone focused on Southern Italy's issues), he criticized the PSI for not caring enough about the problems in the South. He left the Socialist Party but continued to believe in an independent humanitarian socialism. He always worked for big reforms. He was elected to the Italian Chamber of Deputies as an independent radical from 1919 to 1921. This was during a time of great change called the Biennio Rosso. He supported the international plan of national self-determination by US President Woodrow Wilson. This plan suggested adjusting Italy's borders based on clear national lines. This was different from the irredentist (claiming territories based on historical ties) policy of Foreign Minister Sidney Sonnino.

Standing Up to Fascism

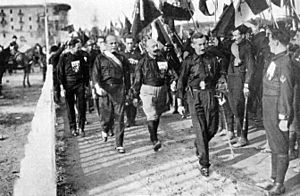

Right after World War I, Salvemini didn't say much about Italian fascism at first. But as a deputy, he soon disagreed with his political group. He started a strong argument against Benito Mussolini. Salvemini had once admired Mussolini as a socialist leader. Their disagreement became so strong that Mussolini even challenged him to a duel, but it never happened. Still, as late as 1922, Salvemini thought the fascist movement was too small to be a serious political threat. He was more against older politicians like Giolitti. He wrote, "A return to Giolitti would be a moral disaster for the whole country." He believed Mussolini was able to take power because "everybody was disgusted by the Chamber."

When Mussolini's March on Rome happened in October 1922, Salvemini was in Paris. This event started the fascist takeover of Italy. In 1923, he gave a series of talks in London about Italian foreign policy. This angered the fascist government and fascists in Florence. Posters appeared on walls in Florence saying, "The monkey from Molfetta should not return to Italy." But Salvemini did return home. He continued his lectures at the University, even with threats from fascist students. He joined the opposition after the murder of the socialist politician Giacomo Matteotti in June 1924. It then became clear that Mussolini wanted to create a one-party dictatorship.

Salvemini worked to keep a strong group of anti-fascist thinkers connected across Italy. This was at a time when much of the Italian academic world supported the fascist government. With his former students and followers Ernesto Rossi and Carlo Rosselli, he started the first secret anti-fascist newspaper. It was called Non mollare ("Don't Give Up") and began in January 1925. Six months later, he was arrested and put on trial. He was released because of a legal technicality, but he was still watched by the police. Threats against his life were printed in fascist newspapers. His lawyer was even beaten to death by fascist thugs. His name was at the top of the list for fascist death squads during raids in Florence in October 1925. However, Salvemini had already escaped to France in August 1925. He was fired from the University of Florence, and his Italian citizenship was taken away in 1926.

In exile, Salvemini continued to actively organize resistance against Mussolini. He worked from France, England, and later the United States. In 1927, he published The Fascist Dictatorship in Italy. This was a clear and important study of how fascism and Mussolini rose to power. In Paris, he helped found Concentrazione antifascista in 1927 and Giustizia e Libertà with Carlo and Nello Rosselli in 1929. Through these groups, Italian exiles helped anti-fascists in Italy and spread secret newspapers. This movement aimed to be a third option between fascism and communism. It wanted a free democratic republic based on social fairness.

Life in the United States

Salvemini first visited the United States in January 1927. He gave lectures with a clear anti-fascist message. His talks were sometimes interrupted by fascist opponents. However, his forced exile gave him a "sense of freedom, of spiritual independence." He preferred to be called a fuoruscito instead of an "exile" or "refugee." Fuoruscito was a term fascists used to insult political exiles, but these exiles adopted it as a symbol of honor. It meant "a man who has chosen to leave his country to continue a resistance which had become impossible at home." He published The Fascist Dictatorship in Italy (1927). This book went against the common belief that Mussolini had saved Italy from Bolshevism.

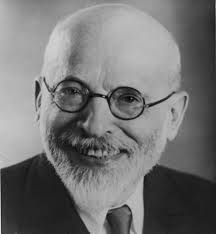

In 1934, Salvemini accepted a special teaching position. He taught Italian civilization at Harvard University, where he stayed until 1948. With Roberto Bolaffio, he started a North American branch of Giustizia e Libertà. He wrote articles in important journals like Foreign Affairs. He also traveled around the country to warn Americans about the dangers of fascism. When Second World War started after Hitler invaded Poland in September 1939, he and other Italian exiles founded the anti-fascist Mazzini Society in Northampton, Massachusetts. Salvemini also joined the Italian Emergency Rescue Committee (IERC). This committee raised money for Italian political refugees and worked to convince American authorities to let them into the country.

He became a US citizen in 1940. He believed this would give him more chances to influence US policies toward Italy. In fact, government agencies like the State Department and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) asked for his advice on fascism and Italian issues. Important books he wrote during his American years include Under the Axe of Fascism (1936). As a scholar, Salvemini greatly influenced the study of Italian history at Harvard and other universities. He changed their focus from just language, art, and literature to a careful and organized study of modern Italy.

As time went on, Max Ascoli, Carlo Sforza, and Alberto Tarchiani became more important in the Mazzini Society. This led to Salvemini becoming less involved in their main decisions. Salvemini worried that President Roosevelt would let Churchill and his conservative plans control Italy after the war. He feared this would benefit the monarchy and those who had worked with Mussolini. After Mussolini fell from power in July 1943, Salvemini became more concerned. He thought the Allies and moderate Italians favored bringing back old conservative ways in Italy. To offer a different idea, Salvemini and Harvard professor Giorgio La Piana wrote What to do with Italy?. In this book, they outlined a plan for Italy's reconstruction after the war. It suggested a republic with social democratic ideas.

Salvemini was also a familiar figure to a young Arthur Schlesinger Jr.. Schlesinger later became an editor for John F. Kennedy's campaign speeches.

Returning to Italy

Even though he was a US citizen, Salvemini returned to Italy in 1948. He was given back his old job as Professor of Modern History at the University of Florence. After 20 years of living in exile, he started his first speech at his old university by saying, "As we were saying in the last lecture." As a left-leaning republican, he was disappointed. The Christian Democratic party won the 1948 general election in Italy, and the Catholic Church had a lot of influence. Salvemini had hoped that the Action Party, a new party that came from Giustizia e Libertà, could be a "third force." He wanted a socialist-republican group that would unite reformist socialists and true democrats. This would be an alternative to the Communists and the Christian Democrats. However, his hopes for a new Italy faded as old ways and institutions returned with the start of the Cold War.

In 1953, his last major historical study was published. It was called Prelude to World War II and was about the Second Italo-Ethiopian War. As a historian, he mainly wrote about recent and modern history. But he was also known for his studies of medieval Italian city-states (called communes). His book The French Revolution: 1788–1792 is an excellent explanation of the social, political, and philosophical ideas (and the king's mistakes) that led to that huge event.

His Final Years and Impact

Salvemini spent his last years in Sorrento. He never stopped speaking out against Italy's old problems. These included inefficiency, scandals, and slow legal processes that often favored powerful people. He also worried about public schools, believing they were not teaching students to think critically. After a long illness, he died on September 6, 1957, at the age of 83.

Salvemini was one of the first and most effective people to oppose fascism. His strong beliefs meant that, according to his biographer Charles L. Killinger, "the Fascists were anti-Salvemini before he became anti-Fascist." Their efforts to silence him made his name stand for early Italian resistance against the new fascist government. Even though he was a very productive historian, he didn't separate his academic work from his political actions. During his exile, he actively organized resistance against Mussolini. He helped others escape Italy. He also played an important role in turning both leaders and the public in America against the fascist government.

Alexander De Grand, who wrote about Giolitti, described Salvemini as a "major historian, driven by an austere moralism." He also called him a "difficult man who attracted deep attachments and bitter enmity." De Grand noted that Salvemini "constantly sought to turn his ideas into practical policy, yet he was a mediocre – no, terrible – politician." Max Ascoli, another Italian exile, described Salvemini "as the greatest enemy of politics of all the men I have known." Despite this, Salvemini was a powerful force who left a lasting mark on Italian politics and the study of history. As a party activist, political writer, and public official, he championed social and political reform. His name is linked to the early Italian resistance against the fascist government. Salvemini often said he tried to live by the principle: "Do what you have to do, come what may."

See also

In Spanish: Gaetano Salvemini para niños

In Spanish: Gaetano Salvemini para niños

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |