Georg Brandes facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Georg Brandes

|

|

|---|---|

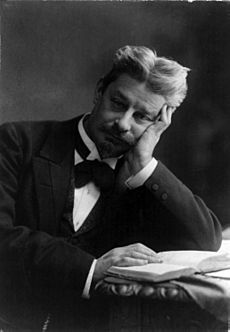

Georg Brandes, sketch, 1900

|

|

| Born | Georg Morris Cohen Brandes 4 February 1842 Copenhagen, Denmark |

| Died | 19 February 1927 (aged 85) Copenhagen, Denmark |

| Occupation | Critic |

| Education | University of Copenhagen |

| Relatives | Edvard Brandes (brother) |

| Signature | |

|

|

Georg Morris Cohen Brandes (born February 4, 1842 – died February 19, 1927) was a Danish writer and thinker. He was a very important critic, someone who studies and judges books and art. He had a huge impact on literature in Scandinavia (countries like Denmark, Norway, and Sweden) and the rest of Europe. This influence lasted from the 1870s into the early 1900s.

Brandes is known as the main thinker behind the "Modern Breakthrough" in Scandinavian culture. When he was 30, he shared his ideas for a new way of writing. He wanted literature to be more about real life (called realism) and nature (called naturalism). He didn't like writing that was too focused on beauty or fantasy. Other writers, like the Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen, shared his goals.

In 1871, Georg Brandes gave a series of lectures called "Main Currents in 19th-century Literature." These talks officially started the "Modern Breakthrough" movement. Later, in 1884, Brandes, his brother Edvard Brandes, and Viggo Hørup started a newspaper called Politiken. Its goal was to bring "greater enlightenment" to people. This newspaper and their political discussions even led to a new political party in Denmark.

Contents

About Georg Brandes

Georg Brandes was born in Copenhagen, Denmark. His family was Jewish, but they didn't strictly follow religious rules. He was the older brother of two other well-known Danes, Ernst Brandes and Edvard Brandes.

In 1859, he started studying at the University of Copenhagen. At first, he studied law, but he soon became more interested in philosophy (the study of knowledge and existence) and aesthetics (the study of beauty and art). In 1862, he won a gold medal from the university for an essay. He also showed a talent for writing poems from 1858, but he didn't publish them until much later, in 1898. When he left the university in 1864, he was greatly influenced by the writer Heiberg and the philosopher Søren Kierkegaard. These influences stayed with him throughout his life.

From 1865 to 1871, Brandes traveled a lot around Europe. He learned about the literature in important cities. His first major book was Aesthetic Studies (1868). This book showed his new way of looking at Danish poets. In 1870, he published more important books. These included The French Aesthetics of the Present Day, which was about the writer Hippolyte Taine. He also published Criticisms and Portraits and translated The Subjection of Women by John Stuart Mill. Brandes had met Mill during a visit to England that year.

The Modern Breakthrough Movement

Brandes quickly became the most important critic in Northern Europe. He used new ways of thinking to look at Danish literature and ideas. He became a teacher of aesthetics at the University of Copenhagen. His lectures were very popular, and many people came to listen.

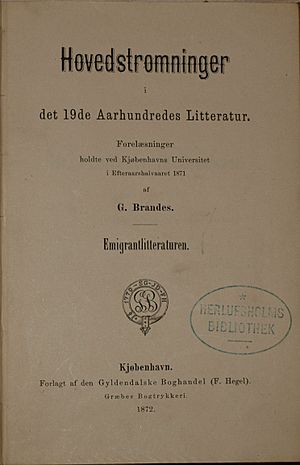

His most famous lecture was on November 3, 1871. It was called Hovedstrømninger i det 19de Aarhundredes Litteratur, which means Main Currents in the Literature of the Nineteenth Century. This lecture marked the start of his long effort to make Danish literature more modern.

When the professor of aesthetics left in 1872, everyone expected Brandes to get the job. However, Brandes had upset many people with his strong support for new ideas. He was seen as a Radical thinker and was even thought to be an atheist (someone who doesn't believe in God). Because of this, the university leaders refused to hire him. But Brandes was so clearly the best person for the job that the position stayed empty for years. No one else wanted to be compared to him.

While these arguments were happening, Brandes started publishing his most important work. It was also called Main Currents in the Literature of the Nineteenth Century. Four volumes came out between 1872 and 1875. This brilliant new way of looking at European literature in the early 1800s quickly gained attention outside Denmark. The excitement around Brandes made his work even more popular, and his fame grew, especially in Germany and Russia.

In 1877, Brandes left Copenhagen and moved to Berlin. He became a big part of the art and literature scene there. But his political ideas made the government in Prussia uncomfortable. So, in 1883, he returned to Copenhagen. There, he found many new writers and thinkers who looked up to him as their leader. He led a group called "Det moderne Gjennembruds Mænd" (The Men of the Modern Breakthrough). This group included writers like J. P. Jacobsen, Holger Drachmann, Edvard Brandes, and the Norwegians Henrik Ibsen and Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson. However, around 1883, some people, led by Holger Drachmann, started to push back against Brandes' "realistic" ideas.

Later Writings

Brandes wrote many books about important people. These include studies on Søren Kierkegaard (1877), Esaias Tegnér (1878), Benjamin Disraeli (1878), Ferdinand Lassalle (1877), Ludvig Holberg (1884), Henrik Ibsen (1899), and Anatole France (1905).

Brandes wrote deeply about the main poets and novelists of Denmark and Norway. For a long time, he and his followers decided which writers would be successful in the Nordic countries. His books like Danish Poets (1877), Men of the Modern Transition (1883), and Essays (1889) are very important for understanding modern Scandinavian literature. He also wrote an excellent book about Poland (1888).

One of his most important later works was his study of William Shakespeare (1897–1898). This book was translated into English and was highly praised. It was one of the most respected books about Shakespeare not originally written for English speakers. Brandes was also working on a history of modern Scandinavian literature.

In all his critical work, Brandes had a wonderful writing style. It was clear and sensible, full of excitement but not over-the-top. He collected his works for the first time in a complete edition in 1900. He also started a German edition, which was finished in 1902. His book Main Currents in Nineteenth-Century Literature was published in 1906. This book was even chosen as one of the 100 best books for education in 1929 by Will Durant.

Personal Life and Final Years

In the late 1880s, Brandes started focusing on "great personalities" as the source of culture. During this time, he discovered the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche. Brandes not only introduced Nietzsche to Scandinavian culture but also, indirectly, to the rest of the world. He gave a series of lectures on Nietzsche's ideas, which he called "aristocratic radicalism." These were the first lectures to show Nietzsche as a major world thinker. Nietzsche himself said that Brandes' description of his philosophy was "very good" and "the cleverest thing that I have yet read about myself."

In 1909, these lectures were published as a book called Friedrich Nietzsche. This book included letters between Nietzsche and Brandes. It was translated into English in 1911, helping Nietzsche's ideas reach many English-speaking readers before World War I. It was Brandes who, in 1888, suggested to Nietzsche that he read the works of Søren Kierkegaard, as their ideas had much in common. However, there is no proof that Nietzsche ever read Kierkegaard's books.

The idea of "aristocratic radicalism" influenced most of Brandes' later works. He wrote long biographies about famous figures like Goethe (1914–15), Voltaire (1916–17), Gaius Julius Cæsar (1918), and Michelangelo (1921).

In the 1900s, Brandes often disagreed with the Danish political system. He had to calm down his strong criticisms sometimes. However, his fame around the world continued to grow. He was like Voltaire, speaking out against old ways of thinking, dishonesty, and false morality. He spoke against the bad treatment of minorities and the unfair trial of Alfred Dreyfus. During World War I, he criticized the aggression and imperialism of all sides. In his last years, he focused on arguing against religion. He also connected with other thinkers like Henri Barbusse and Romain Rolland.

Brandes also argued that Jesus was not a real historical person, but a myth. He published a book called Sagnet om Jesus, which was translated as Jesus: A Myth in 1926. He was an atheist.

Legacy

Brandes is seen as one of the most important people who shaped Danish culture. Many people who supported him believed his work helped free them from strict rules, authority, and dishonesty. He inspired many writers of his time.

His brother Edvard (1847–1931) was also a well-known critic. He wrote plays and two psychological novels. He became an important political figure in the party Det Radikale Venstre.

See also

In Spanish: Georg Brandes para niños

In Spanish: Georg Brandes para niños

- Helen Zelezny-Scholz