Ferdinand Lassalle facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Ferdinand Lassalle

|

|

|---|---|

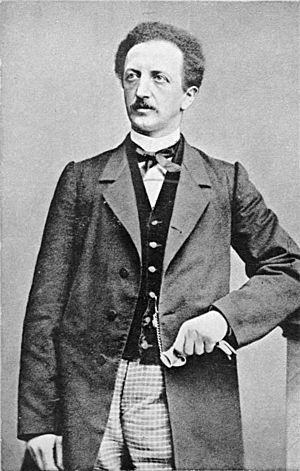

Lassalle in 1860

|

|

| Born |

Ferdinand Johann Gottlieb Lassal

11 April 1825 |

| Died | 31 August 1864 (aged 39) |

| Resting place | Old Jewish Cemetery, Wrocław |

| Nationality | German |

| Political party | General German Workers' Association |

|

Philosophy career |

|

| Era | 19th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy, German philosophy |

| School | Social democracy |

|

Main interests

|

Political philosophy, economics, history |

|

Notable ideas

|

Iron law of wages, Lassallism |

| Signature | |

Ferdinand Lassalle (German: [laˈsal]; 11 April 1825 – 31 August 1864) was a German lawyer, philosopher, and political activist. He is best known for starting the social democratic movement in Germany. He was the first person in Germany to successfully organize a political party focused on helping workers. Lassalle also created important terms like the "night-watchman state" and the "iron law of wages".

Biography

Early life and education

Ferdinand Lassalle was born on April 11, 1825, in Breslau, which is now in Poland. His father was a silk merchant. He wanted Ferdinand to work in business. So, he sent him to a business school in Leipzig.

However, Lassalle soon decided to go to university instead. He studied at the University of Breslau and later at the University of Berlin. He focused on philology (the study of language) and philosophy. He was a big fan of the philosopher Georg Hegel.

Lassalle finished his university studies with excellent grades in 1845. After that, he traveled to Paris. There, he planned to write a book about the ancient Greek philosopher Heraclitus. In Paris, he met the famous poet Heinrich Heine.

Legal work and early activism

When Lassalle returned to Berlin, he met Countess Sophie von Hatzfeldt. She was in her early 40s and was having a long legal fight with her husband over their property. Lassalle offered to help her, and she accepted.

He worked on her case for eight years. He defended her interests in 36 different courtrooms. In the end, the Countess won a lot of money. Because she was so grateful, she agreed to pay Lassalle a yearly income for the rest of his life.

Lassalle was a strong supporter of socialism from a young age. During the German Revolutions of 1848, he spoke at public meetings. He encouraged people in Düsseldorf to be ready to resist if the government became violent.

Because of this, Lassalle was arrested. He was charged with encouraging people to oppose the state. He was found not guilty of this serious charge. However, he was kept in prison for a lesser charge. He was found guilty of encouraging resistance against public officials and spent six months in prison.

Return to politics

After his time in prison, Lassalle was not allowed to live in Berlin. He moved to the Rhineland. There, he continued to work on Countess von Hatzfeldt's lawsuit. He also finished his book on the philosophy of Heraclitus. This book was published in 1858. Some people thought it was a very important work. Even those who disagreed with it admired how much research went into it. The book helped Lassalle become well-known among German thinkers.

For a few years, Lassalle was not very active in politics. He focused on writing a play called Franz von Sickingen, a Historical Tragedy. He wanted to live in Berlin again. In 1859, he returned secretly, dressed as a wagon driver. He asked his friend, the scholar Alexander von Humboldt, to help him. Humboldt spoke to the king, and Lassalle was allowed to live in Berlin again.

Lassalle then became a political writer. He wrote a book about the war in Italy. He also wrote a big book on legal theory in 1861. This book was called The System of Acquired Rights. It looked at when old laws might conflict with new ones.

Lassalle became very active in politics again in 1862. This was because of a struggle over the constitution in Prussia. The king, Wilhelm I, often disagreed with the liberal parliament. Lassalle, as a legal expert, was asked to give speeches about the constitution.

In one speech, he said that constitutional matters are really about who has power. The liberal newspapers were very angry about this. Lassalle gave the same speech two more times. In another speech in Berlin, known as the Workers' Program, Lassalle said that the working class was more important than the middle class. The government saw this as dangerous. They seized all 3,000 copies of his speech.

Lassalle was put on trial in January 1863. He defended himself. He was found guilty and sentenced to four months in prison. Later, this was changed to a fine. Lawsuits continued to affect his political work for the rest of his life.

Founding the socialist party

In October 1862, some workers who had visited London came back with new ideas. They published an open letter about the situation of the working class. Lassalle was excited to see workers with such strong socialist ideas. He wrote his own open letter. In it, he called for a workers' party that would be separate from the liberal German Progress Party.

Lassalle argued that the working class would not gain anything from the liberal party. This started a conflict between him and the liberal party and newspapers. Lassalle began a new role as a political speaker. He traveled around Germany, giving speeches and writing pamphlets. He wanted to organize and inspire the working class. He tried to get workers to break away from the liberals. This eventually led to an alliance with the conservative Prince Bismarck.

In 1864, Lassalle secretly asked Bismarck for help. He wanted Bismarck to support policies like universal suffrage (the right for everyone to vote). He also asked for his writings to be protected from police seizure. Lassalle tried to work with Bismarck. He even wrote a book, Herr Basitat-Schulze, saying it would destroy the liberals. The book was published without police problems. However, Bismarck did not meet with Lassalle again.

The main goal of Lassalle's party was to win equal, universal, and direct suffrage. They wanted to achieve this peacefully and legally.

Personality and influence

People who wrote about Lassalle said he was a complex person. He truly wanted to help ordinary people. But he also had a strong desire for personal success and was very proud.

Bertrand Russell said that Lassalle understood the power of political action and organization very well. Russell believed Lassalle's influence came from his strong will and his belief in his own power to fix problems.

Death and legacy

In the summer of 1864, Lassalle met a young woman named Helene von Dönniges. They decided to get married. However, Helene's family did not approve of Lassalle. Her father, a historian, stopped Helene from seeing him. Helene then chose to marry another man, a prince named Iancu Racoviță, whom she had been engaged to before.

Lassalle challenged both Helene's father and Racoviță to a duel. Racoviță accepted the challenge. Lassalle was not experienced with pistols. The duel took place on August 28 in Carouge, near Geneva. Lassalle was shot and died three days later, on August 31, 1864.

When Lassalle died, his political party had 4,610 members. It did not have a detailed political plan yet. However, the party continued after his death. It later helped to create the Social Democratic Party of Germany in 1875.

Ferdinand Lassalle is buried in Wrocław, Poland, in the Old Jewish Cemetery.

Political relations

Relations with Karl Marx

Lassalle and Marx became friends during the Revolutions of 1848. When the protests ended, Lassalle was imprisoned, and Marx left Germany. They continued to write letters to each other. They did not meet again until 1861.

Over time, Marx grew to distrust Lassalle. This was partly because of Friedrich Engels, who did not like Lassalle much. Marx often wrote friendly letters to Lassalle. But in his letters to Engels, he showed dislike for Lassalle. Lassalle, however, seemed to believe their friendship was real until at least 1862.

Their ideas about politics and theory also differed. Marx's famous essay, Critique of the Gotha Program, was partly a response to Lassalle's ideas within the socialist party. Lassalle was a German patriot. He supported Prussia in its goal of uniting Germany. In 1864, Lassalle wrote that he believed a "social monarchy" could have a great future.

Relations with Otto von Bismarck

On May 11, 1863, Otto von Bismarck, who was the Minister President of Prussia, wrote a letter to Lassalle. They met in person within two days. This was the first of several meetings. During these meetings, Bismarck and Lassalle talked openly about things they both cared about.

These letters and meetings between Bismarck and Lassalle were not made public until 1927. So, earlier biographers did not know about them.

Political ideas

Ferdinand Lassalle died at a young age, only two years after he became deeply involved in German politics. Because of this, his actual contributions to socialist theory are not very large.

The State

Lassalle had different ideas about the state compared to Marx. Marx believed the state was a tool for the ruling class to keep power. He thought it would eventually disappear in a classless society.

Lassalle, however, saw the state as an independent force. He believed it was a tool for justice. He thought the state was essential for achieving a socialist society.

Iron law of wages

Lassalle accepted an idea from the economist David Ricardo. This idea said that wages, over a long time, would only be enough to keep workers alive and allow them to have children. Lassalle called this his "iron law of wages."

He argued that workers trying to improve their lives on their own would fail. He believed that only cooperatives (businesses owned by workers) that received money from the state could truly improve workers' lives. Because of this, he thought that workers needed to take political action to gain control of the state. He felt that forming trade unions just to fight for small wage increases was not the main goal.

Philosophy

Lassalle greatly admired Johann Gottlieb Fichte. He called Fichte "one of the mightiest thinkers of all peoples and ages." In a speech in 1862, he praised Fichte's Addresses to the German Nation. He said it was one of the greatest works our people have, far better than anything similar from history.

Works

German editions

- Die Philosophie Herakleitos des Dunklen von Ephesos (The Philosophy of Heraclitus the Obscure of Ephesus) Berlin: Franz Duncker, 1858.

- Der italienische Krieg und die Aufgabe Preussens: eine Stimme aus der Demokratie (The Italian War and the Tasks of Prussia: A Voice of Democracy). Berlin: Franz Duncker, 1859.

- Das System der erworbenen Rechte (The System of Acquired Rights). Two volumes. Leipzig: 1861.

- Über Verfassungswesen: zwei Vorträge und ein offenes Sendschreiben (On Constitutional Systems: Two Lectures and an Open Letter). Berlin: 1862.

- Offenes Antwortschreiben an das Zentralkomitee zur Berufung eines Allgemeinen Deutschen Arbeiter-Kongresses zu Leipzig (Open Letter Answering the Central Committee on the Convening of a General German Workers' Congress in Leipzig). Zürich: Meyer and Zeller, 1863.

- Zur Arbeiterfrage: Lassalle's Rede bei der am 16. April in Leipzig abgehaltenen Arbeiterversammlung nebst Briefen der Herren Professoren Wuttke und Dr. Lothar Bucher. (On the Labor Problem: Lassalle's Speech on the 16th of April [1863] at a Leipzig Workers' Meeting, Together with the Letters of Professor Wuttke and Dr. Lothar Bucher). Leipzig: 1863.

- Herr Bastiat-Schulze von Delitzsch, der ökonomische Julian, oder Kapital und Arbeit (Mr. Bastiat-Schulze von Delitzsch, the Economic Julian, or, Capital and Labour). Berlin: Reinhold Schlingmann, 1864.

- Reden und Schriften (Speeches and Writings). In three volumes. New York: Wolff and Höhne, n.d. [1883].

- Gesammelte Reden und Schriften (Collected Speeches and Writings). In 12 volumes. Berlin: P. Cassirer, 1919–1920.

- vol. 1 | vol. 2 | vol. 3 | vol. 4 | vol. 5 | vol. 6 | vol. 7 | vol. 8 | vol. 9 | vol. 10 | vol. 11 | vol. 12

English translations

- The Working Man's Programme: An Address. Edward Peters, trans. London: The Modern Press, 1884.

- What is Capital? F. Keddell, trans. New York: New York Labor News Co., 1900.

- Lassalle's Open Letter to the National Labor Association of Germany. John Ehmann and Fred Bader, trans. New York: International Library Publishing, 1901. Originally published in US in 1879.

- Franz von Sickingen: A Tragedy in Five Acts. Daniel DeLeon, trans. New York: New York Labor News, 1904.

- Voices of Revolt, Volume 3: Speeches of Ferdinand Lassalle with a Biographical Sketch. Introduction by Jakob Altmaier. New York: International Publishers, 1927.

See also

In Spanish: Ferdinand Lassalle para niños

In Spanish: Ferdinand Lassalle para niños

- Friedrich Engels, German contemporary who explicitly references Lassalle in his preface to the 1890 German edition of The Communist Manifesto

- General German Workers' Association

- International Workingmen's Association

- Iron law of wages

- Lassallism

- Critique of the Gotha Programme

- Night-watchman state

- Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, French contemporary anarchist theorist

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |