Government in medieval England facts for kids

Imagine a time when kings ruled England, making all the big decisions! In the Middle Ages, the government of the Kingdom of England was a monarchy. This meant a king or queen was in charge. Their power was based on a system called feudalism. The king held the most power in making laws, running the country, and judging cases.

However, by the 1200s, some limits were placed on the king's power. The famous Magna Carta document said that new taxes needed everyone's agreement. Also, the Parliament started to gain power over taxes during this time.

The King's Power

How Kings Inherited the Throne

In the early Middle Ages, there weren't always clear rules about who would become king next. For example, William the Conqueror gave his oldest son, Robert, the land of Normandy. But he gave England to his third son, William II. This often led to fights within the royal family.

When Henry I lost his only son, he decided his daughter, Empress Matilda, should be queen. But many people didn't want a woman ruler, especially since she was married to a French count. After Henry died, Matilda's cousin, Stephen, quickly became king. This started a civil war called the Anarchy. Peace only returned when Stephen agreed to make Matilda's son, Henry II, his heir.

Back then, a new king didn't officially start ruling until his coronation (crowning ceremony). This waiting period could be risky for the country. Sometimes, it was very short, like when Henry I was crowned just three days after William II died. He wanted to secure the throne quickly! Before being crowned, a future king might call himself "Lord of England."

Later, under the Plantagenets family, the rules became clearer. The oldest son usually inherited the throne. A new king was considered to be ruling the moment the old king died. For example, when Henry III died in 1272, his son Edward I became king right away. Edward was away on a Crusade and wasn't crowned until 1274, but he was still king.

English kings were traditionally crowned by the Archbishop of Canterbury at Westminster Abbey. During the ceremony, the king promised to protect the church and his people. He also promised to stop crime and rule fairly. The people present would then agree to him as king. The king was then anointed with special oil, which showed his special connection to God. After this, he was crowned.

What Powers Did the King Have?

Medieval England was a feudal monarchy. This meant the king was like a top boss, and other powerful lords (called vassals) owed him loyalty and service. The king had many rights and powers over these lords. The physical crown became a symbol of all the king's rights.

As the main feudal lord, the king had rights like:

- Taking care of young heirs who were not old enough to rule.

- Arranging or selling marriages for young female heirs and widows.

- Asking for soldiers to fight in his army.

- Asking for special payments (called feudal aid) when his oldest daughter married or his oldest son became a knight.

Kings also had special powers that other lords didn't. Only the king could:

- Make money (coinage).

- Control the main roads.

- Declare war (though it was smart to get Parliament's agreement).

- Not be sued in court.

- Be the only one to judge certain serious crimes.

The king also had a special area around him called the verge. This was a 12-mile zone where only the king's own household courts could hear cases.

Kings could also demand help from their subjects if there was an urgent need. For example, Edward I once took wool from people, saying it was needed for a "certain and urgent necessity."

Limits on the King's Power

Even with all this power, kings faced challenges. Some thinkers believed the king was also under the law. They thought that if a king went too far, his powerful lords should "bridle" him, meaning control him.

Over time, people started to see a difference between the king as a person and the "Crown" as a symbol of royal power. By the time of Edward III, it was clear that royal lands belonged to the Crown, not just to the king himself. This meant kings shouldn't sell off royal lands.

During Edward II's reign, a powerful earl argued that loyalty was owed more to the "Crown" (the idea of kingship) than to the king as a person. One reason Edward II was later removed from power was that he was seen as not protecting the rights of the Crown.

The King's Council

The king had a special group of expert advisers called the king's council. They helped him govern the country. This council dealt with legal matters, money, and talking with other countries. They could even make decisions without following all the usual laws. They could also create new rules.

The council included the king's closest advisers, like judges and important officials such as the chancellor and the treasurer. Members promised to give the king good advice. They often met in a room called the Star Chamber at Westminster Palace.

The Royal Household

The royal household was the heart of the king's government. In the Middle Ages, the king's court and his household were very similar. The household was the group of people who served the king directly. Kings traveled a lot around the country. For example, King John's household moved about 13 times a month! So, the household had to travel with him.

There were about 500 people in the household. The most important part was the wardrobe. It managed the household's money and paid for war expenses. The person in charge of the wardrobe was one of the king's most important ministers. The wardrobe also controlled the privy seal, a special stamp used to send orders to other government offices.

The military part of the household included knights and squires. Besides fighting, they also helped with administration and talking to other countries.

Government Departments

The main office for money was the exchequer. It started under Henry I (1100–1135). The exchequer checked the money records of sheriffs and other royal officials. It later moved to Westminster Hall. The lower exchequer took payments and gave out receipts using tally sticks. The upper exchequer was a court called the Exchequer of Pleas. Its judges, called barons of the exchequer, checked the yearly accounts.

In theory, the exchequer controlled all government money. All royal income was supposed to go there. But sometimes, like during Edward I's reign, the wardrobe (the king's household finance office) worked outside the exchequer's control. Household officials sometimes kept royal money before it reached the exchequer.

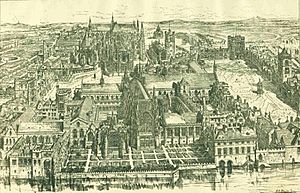

The chancellor was in charge of the chancery, which was the government's writing office. It used to be part of the royal chapel. The clerks there helped with both religious and secretarial tasks for the king. By the time of Edward III, it was permanently based at Westminster.

By 1324, there were about a hundred clerks in the chancery. They produced around 29,000 official documents called writs. Government work could be complicated. Sometimes, three different documents were needed for one royal order, which could cause long delays.

Parliament

Early Councils (924–1215)

Since England became one country in the 900s, kings held national meetings. These meetings included powerful lords and church leaders. The Anglo-Saxons called them witans. These councils helped kings stay connected with important men across the country. They also helped make laws and decide about war and peace. Important trials also happened here.

After the Norman Conquest, this tradition continued. The king regularly got advice from his small "royal court" (curia regis). But he also called larger meetings called "great councils" (magnum concilium). These larger meetings included many lords, bishops, and abbots. They discussed national issues and made laws. For example, the Domesday survey was planned at a council in 1085.

However, these early councils were not like today's parliaments. They were not elected or democratic. They were feudal meetings where lords gave advice to their king. Kings used them to talk with their powerful subjects. But these talks rarely changed the king's plans. Also, these great councils didn't approve taxes. The king could collect taxes whenever he wanted.

Between 1189 and 1215, the great council started to change. This was because the king needed more money for crusades, to pay a ransom for Richard I, and for wars with France. In 1188, the great council agreed to a tax called the Saladin tithe. By doing this, the council was acting for all taxpayers.

It became important for kings to get agreement for national taxes. It was helpful for kings to present the great council as a group that could agree for everyone in the kingdom. People started calling the kingdom the "community of the realm." The powerful lords were seen as their natural representatives. But this also led to more arguments between kings and the lords. The lords wanted to protect what they saw as the rights of the king's subjects.

King John's reign saw the first Magna Carta. A key part, Clause 12, was the start of the idea of "no taxation without representation". It said that certain taxes could only be collected "through the common counsel of our kingdom." Clause 14 said this common counsel should come from bishops, earls, and barons.

Parliament Grows (1215–1307)

Parliament grew out of the great council. It met sometimes when the king called it. Parliament was different because it was seen as an institution for the whole community, not just the king. It represented the people and would "talk" with the king and his council.

Before 1258, making laws wasn't a big part of Parliament's job. It was during Edward I's reign that Parliament passed the first major laws. But these laws weren't actually made by Parliament itself. The king and his council did the real work of law-making. The finished laws were then shown to Parliament for approval.

Parliament successfully gained the right to agree to taxes. A pattern developed: the king would make promises (like confirming Magna Carta) in exchange for Parliament agreeing to new taxes. This was Parliament's main way to influence the king. However, the king could still raise smaller amounts of money without Parliament's approval. These included:

- Money from managing royal lands.

- Profits from royal court visits.

- Taxes on royal lands, towns, foreign traders, and Jewish people.

- Payments from knights instead of military service.

- Feudal fees and fines.

- Money from taking care of young heirs or empty church positions.

Local Government

Counties and Sheriffs

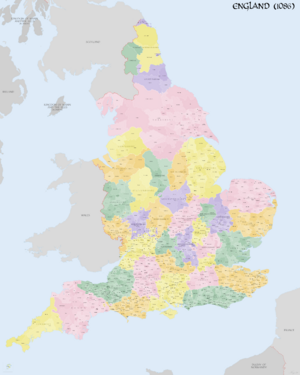

England was divided into 39 areas called counties. These areas stayed mostly the same until 1974.

The most important official in a county was the sheriff. The king chose sheriffs, and they served as long as the king wanted them. The sheriff was in charge of the county court, collected taxes, and paid a fixed amount of money to the king from the county. Sheriffs were the main link between the king and the counties. They announced the king's orders. They had assistants, clerks, and bailiffs.

Being a sheriff was a good way to make money. Sheriffs often kept any extra money they collected after paying the king. Sheriffs were chosen from powerful lords, royal officials, or local wealthy families. Early Norman kings chose local lords. But Henry I preferred to use clerks and knights from his own household. Later, Henry III chose local knights for the job.

The king also appointed officials called escheators. They made sure the king's rights over young heirs were enforced. They also managed lands that returned to the Crown when a lord died without heirs.

Hundreds and Vills

Counties were divided into smaller areas called hundreds. There were 628 hundreds. The hundred court met every two to four weeks. Local landowners attended these meetings. Twice a year, the sheriff would lead the hundred court. He made sure every free adult male was part of a group called a tithing. Members of a tithing were responsible for each other's good behavior. If a tithing failed to catch criminals, they could be fined.

The smallest area was the vill (or township). A group from each vill, including the priest, a local official, and four important men, might have to attend the county court.

Special Local Areas

Sometimes, kings gave counties to relatives for a short time. For example, Henry I gave his wife the county of Shropshire. Richard I gave his brother John six counties, but John lost them after rebelling.

Two counties, Cheshire and Durham, had special freedom from direct royal control. They were called palatine counties. The lord of Chester and the bishop of Durham chose their own sheriffs. By the end of the 1200s, over half of all hundreds were given to powerful lords, bishops, or abbeys. In these areas, the lord's representative ran the hundred court and kept the money from legal fees.

Justice System

Royal Courts

The king was the source of all justice. At first, important cases were heard "in the presence of the king himself." But as the legal system grew, it became more specialized. The king's court split into two main courts at Westminster Hall.

The Court of Common Pleas handled civil cases. These included arguments about debts, property rights, and damage to property. It had a chief justice and several other judges.

In the 1230s, the king's own court became the Court of King's Bench. It used to travel with the king but stayed at Westminster Hall by the 1300s. This court heard appeals from lower courts. It also handled civil cases involving the king and serious criminal cases. It had a chief justice and other judges.

Local Courts

The hundred court dealt with smaller crimes and property arguments. Before Henry II, the county court handled many types of cases. Most land disputes and serious criminal cases were heard there. Henry I even said that land arguments between people from different lords should go to the county court.

County courts met twice a year in Anglo-Saxon times. But by the 1200s, some met every three weeks. The sheriff led the court, and local landowners attended. Local customs played a big role in how these courts worked, and customs varied from county to county.

Henry II also started the general eyres. These were groups of traveling judges who visited different counties. They covered almost the whole country, except for Chester and Durham, which had special status. These judges stayed in a county for several weeks to hear cases. Their cases included royal matters, criminal cases, and issues about the king's rights. By 1189, there were about 35 traveling judges.

The lord of a manor (a local estate owner) could also hold a manorial court for his tenants. These courts handled smaller issues like debts, property damage, and minor fights. Some lords or churches were given special permission to run courts for entire hundreds. These courts could punish minor crimes and even hang thieves caught in the act.

How Trials Worked

In Norman times, court cases involved people making their arguments, information from juries, documents, and witnesses. Often, people would agree to a settlement. If not, they used methods that called on God to show the truth. These included trial by oath (where people swore on the Bible) and trial by ordeal.

In criminal cases, three types of ordeal were used: trial by hot iron, trial by cold water, and trial by combat. Trial by combat was brought by the Normans. It was often used when someone accused another of theft or murder. Civil cases about property could also be decided by combat.

Henry II made important changes that led to the common law. He expanded the use of juries in both criminal and civil cases. A jury was a group of men who swore to tell the truth. In 1166, the Assize of Clarendon said that special juries should identify people suspected of being robbers, murderers, or thieves. They gave this information to the traveling judges. At this time, the jury didn't decide if someone was guilty. That was still done by ordeal.

In civil cases, like land disputes, Henry II introduced the Grand Assize in 1179. This gave people the choice to have a jury of twelve knights decide the matter instead of fighting. He also created "petty assizes" for quick solutions to land arguments. These included procedures where a person could buy a special document (writ) from the chancery. This writ told the sheriff to choose a jury of 12 free men. The jury would then answer a question about the dispute.

In 1215, the Church stopped clergy from taking part in trials by ordeal. So, in 1219, the king ordered judges to find another way. The jury trial was chosen. The first recorded criminal jury trial happened in 1220. Early juries were different from modern ones. Jurors were local people who often knew about the case. Their job was to use their own knowledge to decide the facts, not just weigh evidence.

Punishments

Smaller crimes were punished with amercements, which were financial penalties or fines. The royal Fleet Prison in London opened as early as the 1130s. The Assize of Clarendon also required each county to have a jail in a town or royal castle.

See also

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |