History of monarchy in the United Kingdom facts for kids

The history of the British monarchy shows how it changed from powerful kings and queens to a constitutional monarchy. This means the monarch's power is limited by laws and Parliament. The story of the British monarchy began with small kingdoms in Anglo-Saxon England and early medieval Scotland around the 10th century.

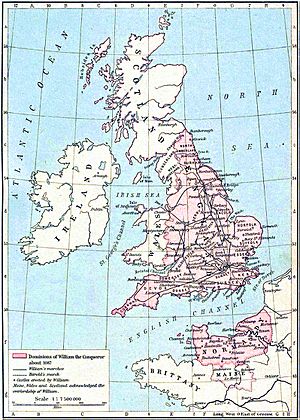

In 1066, the Normans conquered England. They changed how kings were chosen, making it so the eldest son usually inherited the throne. Over time, kings expanded their power across the British Isles, taking over Wales and creating the Lordship of Ireland.

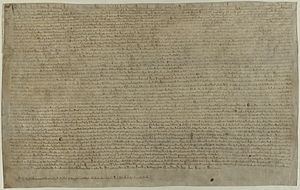

A big change happened in 1215 when King John agreed to Magna Carta. This document limited the king's power. To get support for taxes, English kings started calling meetings of Parliament. Slowly, Parliament gained more power, while the king's power became less.

In 1603, England and Scotland were ruled by the same king, an event called the Union of the Crowns. For a short time, from 1649 to 1660, England became a republic after the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. This meant there was no king or queen. But the monarchy was brought back.

After the Glorious Revolution in 1688, William and Mary became co-monarchs. This firmly established a constitutional monarchy, giving more power to Parliament. The Bill of Rights 1689 further limited the monarch's power and said that only Protestants could become king or queen.

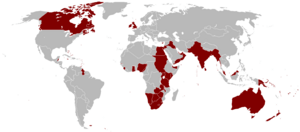

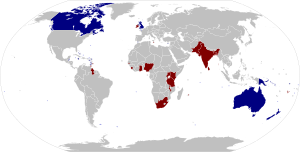

In 1707, England and Scotland joined to form the Kingdom of Great Britain. Then, in 1801, Ireland joined, creating the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. The British monarch was the leader of the huge British Empire, which once covered a quarter of the world's land.

After the Second World War, most British colonies became independent. The British Empire ended, but the monarch still holds the title Head of the Commonwealth. This is a symbol of the free group of independent countries called the Commonwealth of Nations. The United Kingdom and fourteen other countries share the same monarch. These are called Commonwealth realms. Even though they share a monarch, each country is independent.

Contents

- English Monarchy

- Scottish Monarchy

- Irish Monarchy

- Union of the Crowns and Republican Phase

- After the 1707 Acts of Union

- Shared Monarchy and Modern Status

- See also

English Monarchy

Anglo-Saxon Period (800s–1066)

The English monarchy started with the Anglo-Saxons in the 5th and 6th centuries. By the 7th century, they had formed seven kingdoms, sometimes called the Heptarchy. Sometimes, one king was strong enough to be called "bretwalda," meaning "over-king."

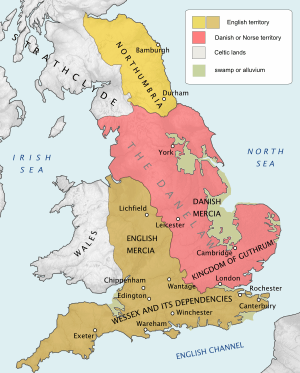

After 865, Viking invaders took over all Anglo-Saxon kingdoms except Wessex. Wessex survived thanks to Alfred the Great (871–899). Alfred called himself "king of the Anglo-Saxons." His son, Edward the Elder (899–924), continued to unite the kingdoms. Alfred's grandsons, Æthelstan (924–939), Edmund I (939–946), and Eadred (946–955), finished taking back the remaining Viking lands. This led to a single Kingdom of England.

In theory, the king had all the power. He made laws, minted coins, collected taxes, and decided foreign policy. But kings needed the support of the Church and the nobles. The king ruled with a council called the Witan, made up of bishops and nobles. The Witan also elected new kings from the royal family. The rule of primogeniture (eldest son inherits) was not yet fixed.

A king's rule was only official after a coronation by the Church. This ceremony gave the ruler a special, almost holy, status. The coronation of Edgar the Peaceful (959–975) became a model for later British coronations. The king promised to protect the Church, defend his people, and be fair.

The capital was Winchester, but the king traveled with his court to different royal estates. The king's money came from his lands, court fines, and trade. A land tax called the geld was also important. Locally, England was divided into shires and hundreds, managed by royal officials.

House of Wessex

Alfred the Great's grandson, Æthelstan (924–939), was the first to use the title "king of the English." He is seen as the founder of the English monarchy. He died without children. His half-brother, Edmund I (939–946), succeeded him. After Edmund's murder, his young sons were passed over for their uncle, Eadred (946–955).

Eadwig (955–959), the eldest nephew, became king. But his younger brother, Edgar (959–975), was soon declared king of Mercia. A civil war was avoided when Eadwig died, and Edgar became king of all England in 959.

Edgar was followed by his son, Edward the Martyr (975–978), who was murdered by his younger brother, Æthelred the Unready (978–1016). Vikings started raiding England again in the 990s. Æthelred tried to pay them off with the Danegeld. In 1013, Sweyn Forkbeard, king of Denmark, conquered England.

After Sweyn's death in 1014, the English invited Æthelred back. He agreed to address complaints about high taxes. This agreement was called "the first constitutional settlement in English history." Æthelred died in 1016, and his son, Edmund Ironside, became king. Sweyn's son, Cnut, invaded and defeated Edmund. They divided England, but Edmund died, and Cnut became king of all England.

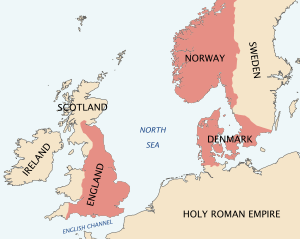

Cnut the Great and His Sons

After Edmund Ironside's death, Cnut (1016–1035) became king of all England. He married Æthelred's widow, Emma of Normandy. Cnut's reign united England with Denmark and Norway, forming what historians call the North Sea Empire. Since Cnut was often away, he divided England into four parts and appointed trusted earls to rule them. The most powerful earl was Godwin of Wessex.

When Cnut died in 1035, his sons fought for the throne: Harthacnut (in Denmark) and Harold Harefoot (in England). Harold became king of Mercia and Northumbria, and Harthacnut became king of Wessex. When Harold died in 1040, Harthacnut reunited England. He ruled until his death in 1042.

Edward the Confessor

Edward the Confessor (1042–1066) was the only surviving son of Æthelred and Emma. He had lived most of his life in Normandy and was more French than English. As king, Edward invited his nephew, Edward the Exile, back to England. Edward the Exile died, but his children, Edgar Ætheling and Margaret, returned. Margaret later married Malcolm III of Scotland.

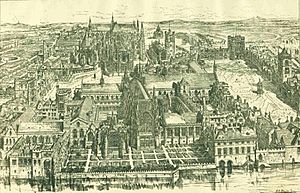

England had a well-organized government. Priests in the king's chapel acted as royal secretaries. Edward appointed the first chancellor, who kept the king's seal. The treasury was also a permanent institution. London became the political and business capital. Edward helped this by building Westminster Palace and Westminster Abbey.

Edward had less land and wealth than Earl Godwin and his sons. To balance their power, Edward created a "French party" loyal to him. He made his nephew, Ralph of Mantes, an earl. In 1051, Edward outlawed the entire Godwinson family, forcing them into exile.

Around this time, Edward invited his relative, William, duke of Normandy, to England. Norman sources say Edward promised William the throne. But Edward's favoritism toward the French was unpopular. With public support, Godwin returned in 1052, and Edward had to give the Godwinsons their lands back.

In 1066, Edward died without children. Edward the Exile's children had the best claim by birth. But Harold Godwinson, Earl of Wessex, claimed King Edward promised him the throne. Harold had more support among the English and was made king by the Witan.

House of Normandy (1066–1154)

William the Conqueror

William, Duke of Normandy, challenged Harold's claim. He said Edward the Confessor promised him the throne. In 1066, William invaded England. Harold was killed at the Battle of Hastings. The English then chose Edgar Ætheling, the Confessor's great-nephew, as king, but he was never crowned. After English resistance failed, Edgar submitted to William. William was crowned king on Christmas Day 1066 at Westminster Abbey.

It took five years of fighting to secure the Norman Conquest. Normans built castles across England for defense and to show their power. In London, William built the White Tower, part of the Tower of London. It was a huge symbol of royal power.

The Conquest brought big changes. Old English became the language of the poor, while French became the language of government. The English nobles were almost completely replaced by new Norman nobles. Most English people lost their land.

The Normans kept the English government, which was more organized than in Normandy. The king's court, called the curia regis, continued the Witan's role of advice. Local courts remained, but the king's court handled serious crimes and appeals. William also kept the Anglo-Saxon practice of sending royal judges to local courts.

English feudalism grew under Norman rule. William I claimed ownership of all land in England. He gave land to his followers, called tenants-in-chief or barons. In return, they promised loyalty and military service. The king also collected money from his estates and taxes.

The Norman kings made nearly a third of England into royal forests for hunting. Special forest laws protected these areas. These laws were unpopular because they limited the rights of other landowners.

The Church was very important to William's conquest. It owned a lot of land. William received the Pope's blessing for his invasion. He separated church cases (like marriage and wills) from secular courts, giving them to church courts. But William also increased royal control over the Church.

Henry I

When William I died in 1087, there were no clear rules for who would be king next. William gave Normandy to his oldest son, Robert, and England to his second son, William II (1087–1100). The Great Hall at Westminster Palace, the king's main home, was built during this time.

On August 2, 1100, William II was killed while hunting. His younger brother, Henry I (1100–1135), was quickly chosen king by the barons and crowned. Henry promised to rule well and restore the laws of Edward the Confessor. This promise was written down as the Coronation Charter, which influenced later documents like Magna Carta.

During Henry's reign, the royal household became more organized. It had departments for royal documents, finances, and travel. The king's closest advisors formed the curia regis. Three times a year, the king met with all his bishops and nobles in a "great council."

The office of justiciar—the king's chief minister—developed. This person acted as a viceroy when the king was in Normandy. The Exchequer was set up to manage royal money, keeping annual records called pipe rolls.

Royal justice became easier to access. Local judges were appointed in each shire, and traveling judges went to different shires. This gave the king more control over local government. Henry I's reforms made the government more organized and efficient.

Succession Crisis

Henry I married Matilda of Scotland, who was related to the old Anglo-Saxon kings. This marriage was seen as uniting the Norman and Wessex royal families. They had two children: Matilda and William Adelin. But in 1120, William Adelin died in a shipwreck, causing a succession crisis.

In 1126, Henry I made the controversial decision to name his daughter, Empress Matilda, as his heir. He forced the nobles to swear loyalty to her. In 1128, Matilda married Geoffrey of Anjou.

Despite the oaths, Matilda was unpopular because she was a woman and because of her marriage to Anjou, an enemy of Normandy. After Henry's death in 1135, his nephew, Stephen of Blois (1135–1154), claimed the throne with the support of most barons. Matilda challenged him, leading to a civil war known as the Anarchy (1138–1153). Stephen kept power, but eventually, they agreed to the Treaty of Wallingford. Stephen adopted Matilda's son, Henry FitzEmpress, as his heir.

Plantagenets (1154–1399)

Henry II

On December 19, 1154, Henry II (1154–1189) became the first king of the new House of Plantagenet. He was also the first king crowned King of England. Henry created the Angevin Empire, which controlled almost half of France.

Henry's first job was to restore royal power after years of civil war. He expelled foreign soldiers and ordered the destruction of illegal castles. He quickly dealt with rebellious lords.

Henry's legal reforms greatly impacted English government. He established the supremacy of royal courts over local and church courts. His reforms made the king's role in justice more organized. Traveling royal judges went across the kingdom. In 1178, the Court of King's Bench was created to hear legal cases full time at Westminster. People could buy royal orders called writs to get royal justice without the king's personal involvement.

Church courts claimed the right to try clergy. These courts had lighter punishments. In 1164, Henry issued the Constitutions of Clarendon, which said that clergy who had been defrocked (removed from their religious office) should be handed over to royal courts for punishment. This also tried to stop appeals to the Pope. Archbishop Thomas Becket opposed these rules, leading to his murder in 1170. Henry later reached an agreement with the Church, allowing appeals to Rome.

Henry also expanded his power outside England. He invaded Wales and received the submission of Welsh leaders. The Scottish king, William the Lion, was forced to accept the English king as his feudal overlord. The Treaty of Windsor in 1175 confirmed Henry as the feudal overlord of most of Ireland.

Richard the Lionheart

After Henry's death, his eldest surviving son, Richard I (1189–1199), known as the Lionheart, became king. He spent only six months in England during his reign. In 1190, Richard left England with a large army to join the Third Crusade to take back Jerusalem. He paid for this by taxes and selling offices and land. While he was away, England was governed by William de Longchamp, who held many powerful positions.

Richard was imprisoned by the Holy Roman Emperor Henry VI for over a year while returning from the Crusade. England had to pay a huge ransom to free him. In 1193, Richard's brother, John, sided with Philip II of France to try and take Richard's lands in France. Richard returned to England in 1194 but soon left to fight Philip II. By 1198, Richard had won back most of his territory. In 1199, Richard died from wounds received during a siege. Before he died, he named John as his successor.

After Richard returned from the Crusade, he created the office of coroner. Coroners were royal officers who, along with sheriffs, helped administer justice in each shire.

John

In May 1199, John (1199–1216) was crowned King of England. In 1204, John lost Normandy and his other lands in France. The rest of his reign was spent trying to regain his military reputation and fund wars. Traditionally, the king paid for government from his own income. But this was hard, especially during war. To fund his campaigns, John introduced a 13% tax on income and goods. He also charged high court fees and, in his barons' opinion, unfairly used his feudal rights. These actions and his paranoia made his relationship with the barons very bad.

After arguing with the king about choosing a new Archbishop of Canterbury, Pope Innocent III placed England under a papal interdict in 1208. For six years, priests could not hold mass or perform marriages. John responded by taking Church property. In 1209, the Pope excommunicated John. John finally made peace with the Pope in 1213, even making England a papal fief, meaning he was the Pope's vassal.

The war with France in 1213–1214 was fought to restore the Angevin Empire, but John was defeated. His military and financial losses in 1214 weakened him greatly. The barons demanded that he rule according to Henry I's Coronation Charter. On May 5, 1215, a group of barons rebelled and chose Robert Fitzwalter as their leader. After a month of talks, they agreed to the Magna Carta (Latin for "Great Charter") at Runnymede on June 15.

This document defined and limited the king's powers. It said that "No free man shall be taken or imprisoned... except by lawful judgment of his peers or by the law of the land." It also said, "To no one will we sell, to no one will we deny or delay right or justice." These clauses were meant to stop the king from using his power unfairly.

Magna Carta included a way to enforce it: a council of 25 barons could rebel if the king broke the charter. But John had no intention of following it. He appealed to Pope Innocent, who cancelled the agreement and excommunicated the rebel barons. This started the First Barons' War. The rebels offered the crown to Philip II's son, Louis VIII of France. By June 1216, Louis controlled half of England, including London. John died suddenly on October 19.

Henry III

After John's death, his nine-year-old son, Henry III (1216–1272), was quickly crowned. This set the rule that the eldest son became king regardless of age. William Marshal, Earl of Pembroke, served as regent (ruler for a young king) until 1219. Marshal led royal forces to victory against the rebels and French invaders.

During Henry's reign, the idea that kings must follow the law became accepted. To gain support, his government re-issued Magna Carta in 1216 and 1217. In 1225, Magna Carta was re-issued in exchange for a tax to fund wars in France. This set a new rule: military campaigns would be paid for in return for political freedoms. In 1236, Henry started calling these meetings Parliament. By the 1240s, Parliament could grant taxes and nobles could complain about government.

In 1227, Henry was 18, and the regency ended. But he often favored foreign friends. After his chief minister, Hubert de Burgh, fell from power, Bishop Peter des Roches became influential. He gave many offices to his relatives, who were foreigners. This angered the English nobles. The bishops threatened Henry with excommunication, forcing him to remove the foreign party from power.

Henry then favored his half-brothers from Lusignan. By the 1250s, there was widespread anger against them. There was also opposition to Henry's plans to conquer Sicily for his second son. In 1258, the king was forced to accept a reform program at the Oxford Parliament. The Provisions of Oxford transferred royal power to a council of fifteen barons. Parliament would meet three times a year and appoint all royal officers. The new government was led by Simon de Montfort, the king's brother-in-law.

When the king tried to overturn the Provisions of Oxford, Montfort led a rebellion, the Second Barons' War. In 1265, Montfort called a Parliament that included knights and citizens from important towns for the first time. This was a big step in Parliament's development. Montfort was killed in 1265, and royal authority was restored.

Henry III spent a lot of money on royal palaces, especially rebuilding Westminster Palace and Abbey. These projects nearly bankrupted the king. Henry III died in 1272, after ruling for 56 years.

Edward I

Edward I (1272–1307), known as Longshanks, was in Italy when his father died. His reign officially began on November 20, the day his father was buried. Regents were appointed to rule until he returned. Edward wanted to restore royal authority. He ordered a survey to find out what lands and rights the Crown had lost.

Edward understood the importance of Parliament. He usually called Parliament twice a year. He passed many laws through Parliament. In 1297, he reissued Magna Carta. In 1295, Edward called the Model Parliament, which included knights and citizens to represent the counties and towns. These "middle earners" were important taxpayers, and Edward wanted their financial support for an invasion of Scotland.

Edward used Parliament to fund his military campaigns in Wales and Scotland. He successfully conquered Wales, built castles, and brought the country under English law. In 1301, the king's eldest son, Edward of Caernarfon, was made Prince of Wales. This title is still given to the heirs of British monarchs.

When Alexander III of Scotland died in 1286, and his granddaughter Margaret died in 1290, the Scottish throne was empty. Scottish leaders asked Edward to decide who should be king. Edward chose John Balliol but treated him as a vassal. When Balliol renounced his loyalty, Edward I invaded, starting the First War of Scottish Independence. Edward died in 1307 on his way to invade Scotland again.

Edward II

At his coronation, Edward II (1307–1327) promised to uphold the laws chosen by the "community of the realm." This meant he accepted that he needed to rule with Parliament. The new king inherited debt and a failing war in Scotland. He made things worse by angering the nobles, mainly because he relied too much on royal favorites like Piers Gaveston and Hugh Despenser the Younger.

The nobles blamed these favorites for unpopular policies. In 1308, Parliament made a clear distinction between the king as a person and the Crown as an institution. In 1310, Parliament complained that the kingdom had gotten worse since Edward I's death. They accused Edward II of being guided by bad advisors, wasting royal money, breaking Magna Carta, and losing Scotland.

The nobles elected 21 "ordainers" to reform the government. Their reforms, called the Ordinances of 1311, tried to limit the king's power. They banned going to war without Parliament's consent and said Parliament should meet at least once a year. They also said Parliament should appoint royal ministers.

The Ordinances required Gaveston to be exiled. But Edward brought him back. Earl Thomas of Lancaster, the king's cousin, led nobles who captured and executed Gaveston. This almost caused a civil war.

After Gaveston's death, Hugh Despenser and his son, Hugh the Younger, became the most influential men around the king. Edward's favoritism toward the Despensers continued to upset the kingdom. The Despensers controlled access to the king and used their power to take land from their enemies. In 1321, nobles invaded the Despenser estates, starting the Despenser War. Edward defeated the nobles in 1322 and overturned the Ordinances. For a few years, Edward ruled like a tyrant.

In 1324, Edward's wife, Isabella, and their son, Prince Edward, went to France. There, the Queen allied with Roger Mortimer, a noble who had fought against Edward. They invaded England in 1326. Many nobles joined the Queen, and London revolted. The King and the Despensers fled but were captured.

It was clear Edward II could not remain king, but there was no legal way to remove a crowned king. At the Parliament of 1327, accusations were made against the king for breaking his coronation oath. On January 20, Edward II was forced to abdicate (give up his throne). This was the first time an English monarch was formally removed. The former king died on September 21, likely murdered.

Edward III

Five days after his father's abdication, the 14-year-old Edward III (1327–1377) was crowned king. But Isabella and Mortimer truly held power. Their rule weakened the monarchy. They made a bad treaty with France and failed to claim the French throne. They also gave up England's claim to overlordship of Scotland. At home, Mortimer used his power to get rich, while the country faced crime and debt. In 1330, Mortimer had the King's uncle arrested and executed.

On October 19, 1330, the 17-year-old Edward staged a coup at Nottingham Castle. Mortimer was arrested, tried by Parliament, and executed. The young King, now in full control, realized he needed to work with the English nobles. He strengthened ties between the king and nobles, especially through frequent tournaments where Edward himself took part. Edward was the first king since the Conquest to speak English.

In 1333, Edward invaded Scotland and won a major victory. He placed Edward Balliol on the Scottish throne as his vassal. But with French help, the Scots continued to resist.

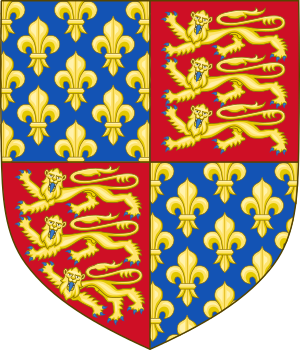

In 1337, Edward created six new earldoms to gain military support for a war against France. His eldest son, Edward of Woodstock, was made Duke of Cornwall, the first duchy in England. In May 1337, the French king took back English lands in France. In 1340, Edward claimed the French throne. To show this, he added the French fleur-de-lis to the royal arms of England.

In 1346, Edward invaded France, starting the Hundred Years' War. The English won the Battle of Crécy and took Calais, which remained English for two centuries. After a successful campaign, Edward founded the Order of the Garter at Windsor Castle in 1348. He spent a lot of money transforming Windsor into a magnificent castle.

The King's eldest son, Edward the Black Prince, won the Battle of Poitiers in 1356, capturing the French king. In the Treaty of Brétigny of 1360, Edward gave up his claims to the French throne in return for full control over some French territories. He also made peace with Scotland.

Edward worked with Parliament to get support for his wars, which helped Parliament grow. Parliament was consulted on war and peace treaties. The long wars made taxation normal. Direct taxes were for war, but indirect taxes on trade became permanent, increasing royal power.

In Edward's last years, there were setbacks. The French drove the Black Prince out of Aquitaine. Prince Edward returned to England in poor health and died at 45. The elderly King's illness created a power vacuum. In the Good Parliament of 1376, the House of Commons refused to fund the war until corrupt ministers and the king's mistress were removed. The accused ministers were arrested and tried by Parliament in the first impeachment proceedings.

Edward's new heir was his nine-year-old grandson, Richard of Bordeaux. To strengthen the boy's position, he was recognized in Parliament as heir apparent and given royal titles. Edward III died in 1377.

Richard II

Richard II (1377–1399) was ten years old when he became king. No regent was set up because his uncle, John of Gaunt, was unpopular. Richard theoretically ruled with an advisory council, but his uncles and courtiers held much power. In 1381, anger over taxes led to the Peasants' Revolt. The 14-year-old king's brave leadership ended the revolt, showing he was ready to rule. But the revolt also made him believe that disobedience was a threat to order.

After the revolt, Parliament appointed Michael de la Pole to advise the King. Pole became chancellor. The King's most important favorite was Robert de Vere. Richard gave de Vere new titles, placing him above other nobles. This favoritism angered other aristocrats, including the King's uncles.

Another complaint was the situation in France. England had lost most of its French lands. Richard led an invasion of Scotland in 1385 that achieved nothing. He spent a lot on palace renovations and court entertainment.

In 1386, Pole asked for more money to defend England. But Parliament, led by Richard's uncle Thomas of Woodstock, refused until Pole was removed. Richard refused but gave in after being threatened with removal. A council was set up to manage royal finances and power. At 19, the King was again a figurehead. Richard defied them and toured the country to gather an army.

Richard returned to London in November 1387. Three nobles, including his uncle Thomas, accused Pole, de Vere, and other royal associates of treason. These Lords Appellant defeated Richard's army. The King had to agree to their demands. At the Merciless Parliament of 1388, Richard's favorites were found guilty of treason.

After his favorites were removed, the Lords Appellant were content. In 1389, Richard regained royal authority and made peace with John of Gaunt. For a time, Richard ruled well. He led a successful trip to Ireland in 1394 and made a 28-year truce with France in 1396. In July 1397, Richard finally moved against his enemies. The three Lords Appellant were arrested and found guilty of treason.

For the next two years, Richard ruled like a tyrant, forcing loans from his subjects. The king had no children, making the succession uncertain. The strongest claim was Henry Bolingbroke, John of Gaunt's son. In 1397, Bolingbroke was banished from England for 10 years. When John of Gaunt died in 1399, Richard took his lands and extended Bolingbroke's banishment for life.

In May 1399, Richard went on a second invasion of Ireland. Bolingbroke returned to England in July with a small force but quickly gained support from powerful nobles. Richard returned to England, but his army disappeared. By September 2, Richard was a prisoner in the Tower.

On September 30, an assembly of the House of Lords and House of Commons met. They said Richard had agreed to abdicate. When asked if they accepted, the lords agreed, and the Commons shouted their agreement. Thirty-nine articles of deposition accused Richard of breaking his coronation oath. After Richard's removal was announced, Bolingbroke claimed the Crown. He was seated on the empty throne to shouts of approval.

Richard II was not the first English monarch to be removed. Edward II was also removed, but he abdicated in favor of his son. In Richard's case, Parliament deliberately broke the line of succession. This created a dangerous situation for future kings.

House of Lancaster (1399–1461)

Henry IV

Bolingbroke was crowned Henry IV (1399–1413) two weeks after Richard II's removal. His family was known as the House of Lancaster. At his coronation, Henry started the tradition of creating Knights of the Bath. He was also the first English monarch crowned on the Stone of Scone, which Edward I had taken from Scotland.

In January 1400, a rebellion tried to free Richard and restore him. Henry realized he would not be safe as long as Richard lived, so he ordered his death. Henry's reign was always affected by the removal and murder of a king. He constantly fought plots and rebellions. In 1400, the Welsh Revolt began. Henry Hotspur joined the revolt in 1403 but was defeated.

When he overthrew Richard, Henry had promised lower taxes. Parliament held him to this, refusing to raise taxes even when the king was in debt. Henry benefited from inheriting his father's large Lancastrian estates. He kept these lands separate from the Crown lands, a practice continued by later monarchs.

Charles VI of France, Richard's father-in-law, refused to recognize Henry. The French attacked Calais and helped the Welsh Revolt. But in 1407, a civil war divided France, and the English tried to take advantage. As the king's health declined, his eldest son, Henry of Monmouth, took a greater role in government.

Henry V

Henry IV died in 1413, and his son became King Henry V (1413–1422). He made peace with his father's enemies. He also honored the deceased Richard II by giving him a royal re-burial.

Henry V's reign was mostly free from internal conflict, allowing him to focus on the war with France. The war was popular, and Parliament readily gave money to fund the campaign, which began in August 1415. Henry won a famous victory at the Battle of Agincourt. The triumphant king returned home to a nation eager for more conquests. Parliament granted him lifetime duties on wine imports and other taxes.

In 1419, he conquered Normandy. In 1420, the Treaty of Troyes recognized Henry as the heir and regent of the French king, Charles VI. This peace was sealed by Henry's marriage to the French princess Catherine of Valois. Charles's son, the Dauphin, was disinherited but continued to claim the French throne.

Henry V was a popular king who restored royal authority and reduced crime. England prospered under him. He kept his personal expenses low and managed royal finances well. But Henry's frequent absences in France caused problems. He insisted on dealing with Parliament's requests personally, causing delays. By 1420, the House of Commons was complaining, and it was harder to get funds for more wars. On August 31, 1422, the king fell ill and died during another campaign in France.

Henry VI

Only nine months old when his father died, Henry VI was the youngest person to inherit the English crown. On October 21, 1422, Charles VI of France died. The infant Henry was now king of England and France, creating a dual monarchy.

Henry V's will put his brother, John, duke of Bedford, in charge of France. In England, his other brother, Humphrey, duke of Gloucester, was made lord protector and head of a regency council that ruled in the king's name.

Henry VI's young age gave the French a chance to overthrow English rule. The unpopularity of Henry VI's advisors and his wife, Margaret of Anjou, along with his own weak leadership, weakened the House of Lancaster. The Lancastrians faced a challenge from the House of York, led by Richard, Duke of York, who was at odds with the Queen.

House of York (1461–1485)

Although the Duke of York died in battle in 1460, his eldest son, Edward IV, led the Yorkists to victory in 1461. He overthrew Henry VI and Margaret of Anjou. Edward IV constantly fought with the Lancastrians and his own advisors after marrying Elizabeth Woodville. Henry VI briefly returned to power. Edward IV won back the throne and killed the Lancastrian heir. He captured Margaret of Anjou and later killed Henry VI while he was a prisoner. The Wars of the Roses continued during his reign and those of his son Edward V and brother Richard III. Edward V disappeared, likely murdered by Richard. Finally, Henry Tudor, a Lancastrian, won in 1485 when Richard III was killed at the Battle of Bosworth Field.

Tudors (1485–1603)

King Henry VII then dealt with the remaining Yorkist forces, partly by marrying Elizabeth of York, a Yorkist heir. Henry skillfully re-established strong royal power, and the conflicts with the nobles that had troubled earlier kings ended. The reign of the second Tudor king, Henry VIII, brought great political change. Religious unrest and disagreements with the Pope, along with the fact that his marriage to Catherine of Aragon produced only one surviving child (a daughter), led him to break from the Roman Catholic Church. He established the Church of England and divorced his wife to marry Anne Boleyn.

Wales, which had been conquered centuries earlier but remained separate, was joined with England under the Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542. Henry VIII's son, the young Edward VI, continued religious reforms. But his early death in 1553 caused a succession crisis. He did not want his Catholic elder half-sister, Mary I, to become queen. He named Lady Jane Grey as his heir. However, Jane's reign lasted only nine days. With huge popular support, Mary removed her and declared herself the rightful queen. Mary I married Philip of Spain, who was declared king and co-ruler. She tried to return England to Roman Catholicism, burning Protestants as heretics. When she died in 1558, her Protestant half-sister, Elizabeth I, succeeded her. England returned to Protestantism and grew into a major world power by building its navy and exploring new lands.

Scottish Monarchy

In Scotland, like in England, monarchies appeared after the Roman Empire left Britain in the 5th century. The three main groups living in Scotland were the Picts, the Britons, and the Gaels or Scotti. Kenneth MacAlpin is traditionally seen as the first king of a united Scotland. Scottish lands continued to expand over the next two centuries.

Early Scottish kings did not inherit the Crown directly. Instead, they followed a custom called tanistry, where the monarchy switched between different branches of the royal family. This often led to violent clashes. From 942 to 1005, seven kings were murdered or killed in battle. In 1005, Malcolm II became king after killing many rivals. He continued to remove opposition. When he died in 1034, his grandson, Duncan I, succeeded him, which was unusual. In 1040, Duncan was defeated and killed by Macbeth. Macbeth was killed in 1057 by Duncan's son, Malcolm. The next year, Malcolm became king as Malcolm III.

Five of Malcolm's sons and one of his brothers became king. Eventually, the Crown went to his youngest son, David I. David was succeeded by his grandsons, Malcolm IV and then William the Lion. William was the longest-reigning King of Scots before the Union of the Crowns. William rebelled against King Henry II of England but was captured. To be released, William had to recognize Henry as his feudal overlord. The English King Richard I ended this agreement in 1189 for a large sum of money. William died in 1214, and his son, Alexander II, became king. Alexander II and his successor, Alexander III, tried to take over the Western Isles, which were under Norway's rule. During Alexander III's reign, Norway invaded Scotland but failed. The Treaty of Perth recognized Scottish control of the Western Isles.

Alexander III's death in a riding accident in 1286 caused a major succession crisis. Scottish leaders asked King Edward I of England to help decide the rightful heir. Edward chose Alexander's three-year-old granddaughter, Margaret. But Margaret died at sea in 1290. Edward was again asked to choose between 13 rival claimants. After two years, John Balliol was chosen king. Edward treated Balliol as a vassal and tried to control Scotland. In 1295, Balliol renounced his loyalty, and Edward I invaded. For the next ten years, Scotland had no monarch, until Robert the Bruce declared himself king in 1306.

Robert's efforts led to Scottish independence being recognized in 1328. However, only a year later, Robert died. His five-year-old son, David II, succeeded him. The English invaded again in 1332, trying to restore John Balliol's heir, Edward Balliol. Balliol was crowned, removed, restored, and removed several times. David remained king for the next 35 years.

David II died childless in 1371. His nephew, Robert II of the House of Stuart, became king. The reigns of Robert II and his successor, Robert III, saw a decline in royal power. When Robert III died in 1406, regents had to rule because the king, Robert III's son James I, had been captured by the English. After paying a large ransom, James returned to Scotland in 1424. He used harsh methods to restore his authority and was assassinated by nobles. James II continued his father's policies but was killed in an accident at 30. A council of regents again took power. James III was defeated in battle against rebellious Scottish earls in 1488, leading to another boy-king: James IV.

In 1513, James IV invaded England, hoping to take advantage of King Henry VIII's absence. His forces were defeated at Flodden Field. The King, many nobles, and hundreds of soldiers were killed. His son and successor, James V, was an infant, so regents again governed. James V led another disastrous war with the English in 1542. His death that year left the Crown to his six-day-old daughter, Mary. A regency was established once more.

Mary, a Roman Catholic, ruled during a time of great religious change in Scotland. Protestantism grew strong. Mary caused alarm by marrying her Catholic cousin, Lord Darnley. After his murder in 1567, Mary married the Earl of Bothwell, who was suspected of Darnley's murder. The nobles rebelled, forcing Mary to give up her throne. She fled to England. The Crown went to her infant son, James VI, who was raised as a Protestant. Mary was imprisoned and later executed by the English queen Elizabeth I.

Irish Monarchy

Ireland was historically divided into small kingdoms. In 1155, the only English pope, Adrian IV, allowed Henry II of England to conquer Ireland and reform the Irish Church. However, Henry did not act until 1171. By then, English nobles had already invaded Ireland and controlled parts of it. In 1171, Henry landed in Ireland, and the Anglo-Norman lords and native Irish nobles swore loyalty to him. In 1185, Henry gave his youngest son, King John of England, the title Lord of Ireland. John was sent to Ireland to be crowned, but his behavior offended the Irish, and he left without being crowned. After that, English kings used the title Lord of Ireland but mostly ruled through lieutenants.

By 1541, King Henry VIII of England had broken with the Church of Rome. The Pope's grant of Ireland to the English monarch was no longer valid. So, Henry called a meeting of the Irish Parliament to change his title from Lord of Ireland to King of Ireland. In 1800, after the Irish Rebellion of 1798, the Act of Union merged the kingdom of Great Britain and the kingdom of Ireland into the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

Union of the Crowns and Republican Phase

Elizabeth I's death in 1603 ended Tudor rule in England. Since she had no children, the Scottish monarch James VI became king. He was the great-grandson of Henry VIII's older sister. James VI ruled in England as James I, in what was called the "Union of the Crowns". England and Scotland had the same king, but they remained separate kingdoms. James I & VI became the first monarch to call himself "King of Great Britain" in 1604.

James I & VI's successor, Charles I, often argued with the English Parliament about royal and parliamentary powers, especially taxes. He ruled without Parliament from 1629 to 1640, collecting taxes and making religious policies that offended Scottish Presbyterians and English Puritans. His attempts to enforce Anglicanism led to rebellion in Scotland and started the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. In 1642, the conflict between the King and Parliament led to the English Civil War.

The Civil War ended with the execution of the king in 1649. The English monarchy was overthrown, and the Commonwealth of England (a republic) was established. Charles I's son, Charles II, was proclaimed King in Scotland, but he had to flee abroad after being defeated in England. In 1653, Oliver Cromwell, a military leader, took power and declared himself Lord Protector. He ruled like a military dictator but refused the title of king. Cromwell ruled until his death in 1658, and his son Richard succeeded him. Richard had little interest in governing and soon resigned. This lack of leadership led to unrest and a desire to bring back the monarchy. In 1660, the monarchy was restored, and Charles II returned to Britain.

Charles II's reign saw the development of the first modern political parties. Charles had no legitimate children, and his Catholic brother, James, Duke of York, was next in line. Parliament tried to exclude James from the line of succession. The "Petitioners" who supported this became the Whig Party, and those who opposed it became the Tory Party. The exclusion bill failed. Charles II sometimes dissolved Parliament to prevent the bill from passing. After 1681, Charles ruled without Parliament until his death in 1685.

When James became king, he tried to offer religious tolerance to Roman Catholics, which angered many Protestants. Many opposed James's large army and his appointment of Catholics to high offices. A group of Protestants invited James II & VII's daughter Mary and her husband William III of Orange to remove the king. William arrived in England in 1688 with public support. James fled, and William and Mary were declared joint Sovereigns of England, Scotland, and Ireland.

James's overthrow, known as the Glorious Revolution, was very important for Parliament's power. The Bill of Rights 1689 confirmed Parliament's power. It said that English people had rights, including freedom from taxes without Parliament's consent. The Bill of Rights required future monarchs to be Protestants. After William and Mary's children, Mary's sister Anne would inherit the Crown. Mary II died childless in 1694, leaving William III & II as the sole monarch. By 1700, all of Anne's children had died, leaving her as the only person left in the line of succession. Parliament feared that James II or his supporters might try to reclaim the throne. Parliament passed the Act of Settlement 1701, which excluded James and his Catholic relatives from the succession. It made William's nearest Protestant relatives, the family of Sophia, Electress of Hanover, next in line after Anne. Soon after, William III & II died, and Anne became queen.

After Anne became queen, the succession problem reappeared. The Scottish Parliament was angry that the English Parliament did not consult them on the choice of Sophia's family as heirs. They passed the Act of Security 1704, threatening to end the personal union between England and Scotland. The English Parliament responded with the Alien Act 1705, threatening to harm the Scottish economy. The Scottish and English parliaments negotiated the Acts of Union 1707, which united England and Scotland into a single Kingdom of Great Britain. The succession would follow the rules of the Act of Settlement.

After the 1707 Acts of Union

In 1714, Queen Anne was succeeded by her second cousin, George I, who was also the Elector of Hanover (a German kingdom). He secured his position by defeating Jacobite rebellions. The new king was less involved in government than earlier British monarchs. Power shifted to his ministers, especially Sir Robert Walpole, who is often considered the first British prime minister. The next monarch, George II, saw the final end of the Jacobite threat in 1746. During the long reign of his grandson, George III, Britain lost its American colonies, which formed the United States of America. However, British influence grew elsewhere, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was created in 1801.

From 1811 to 1820, George III suffered from an illness that made him unable to rule. His son, the future George IV, ruled in his place as Prince Regent. During this period and his own reign, the monarchy's power declined. By the time of his successor, William IV, the monarch could no longer effectively interfere with Parliament. In 1834, William dismissed the Prime Minister, but the new one lost the elections, and the king had to recall the old Prime Minister. During William IV's reign, the Reform Act 1832 was passed, which changed how Parliament was represented. This led to more people being able to vote and the House of Commons becoming the most important part of Parliament.

The final shift to a constitutional monarchy happened during the long reign of William IV's successor, Victoria. As a woman, Victoria could not rule Hanover, which only allowed male succession. So, the personal union of the United Kingdom and Hanover ended. The Victorian era was a time of great cultural change, technological progress, and Britain becoming a leading world power. Victoria was declared Empress of India in 1876. However, her reign also saw increased support for a republic, partly because of Victoria's long period of mourning after her husband's death in 1861.

Victoria's son, Edward VII, became the first monarch of the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha in 1901. In 1917, the next monarch, George V, changed the family name to "Windsor" because of anti-German feelings during the First World War. George V's reign also saw Ireland separate into Northern Ireland (part of the UK) and the Irish Free State (an independent nation) in 1922.

In the 20th century, the British Empire evolved into the Commonwealth of Nations. Before 1926, the British Crown ruled the Empire as a whole. But the Balfour Declaration of 1926 gave complete self-government to the Dominions (self-governing countries within the Empire). This meant a single monarch acted independently in each separate Dominion. The idea was made official by the Statute of Westminster 1931.

So, the monarchy stopped being only a British institution. The monarch became separately the monarch of the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and so on. The independent countries in the Commonwealth share the same monarch, like a personal union.

George V's death in 1936 was followed by Edward VIII. He caused a public scandal by wanting to marry the divorced American Wallis Simpson, even though the Church of England opposed remarriage for divorced people. Edward decided to give up his throne. The Parliaments of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth countries agreed. Edward VIII and any children from his new wife were excluded from the line of succession. The Crown went to his brother, George VI. George was a symbol of strength for the British people during World War II, visiting troops and factories. In June 1948, George VI gave up the title Emperor of India.

At first, every Commonwealth member had the same monarch as the United Kingdom. But when India became a republic in 1950, it no longer shared a common monarchy. Instead, the British monarch was recognized as "Head of the Commonwealth" in all Commonwealth member states, whether they were realms or republics. This position is purely ceremonial and is not automatically inherited. Member states that share the same person as monarch are called Commonwealth realms.

In the 1990s, support for a republic in the United Kingdom grew, partly due to negative publicity about the Royal Family. However, polls from 2002 to 2007 showed that about 70–80% of the British public supported keeping the monarchy. This support has remained steady.

See also

- History of monarchy in Australia

- History of monarchy in Canada

- Family tree of British monarchs

- List of British royal residences

- List of English ministries

|

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |