Castles in Great Britain and Ireland facts for kids

Castles are strong, fortified homes that have been very important in Great Britain and Ireland for a long time. They became common after the Normans invaded England in 1066. Before that, some castles were built in England in the 1050s.

The Normans quickly built many castles, like motte and bailey and ring-work castles. These helped them control the new lands they had taken over in England and near Wales. By the 12th century, Normans started building more castles from stone. These stone castles often had a big square tower called a keep. They were used for both military control and political power.

Royal castles helped control important towns and valuable forests. Castles owned by powerful Norman lords, called barons, helped them manage their large lands. In the early 12th century, King David I of Scotland invited Norman lords to his country. They brought castle-building skills, and wooden castles began to appear in southern Scotland. After the Norman invasion of Ireland in the 1170s, castles were also built there.

Castles became more advanced for military use and more comfortable for living during the 12th century. This made sieges (when an army surrounds a castle to take it) much harder and longer in England. In Ireland and Wales, castles continued to be built like those in England. But in Scotland, after King Alexander III died, people started building smaller tower houses instead of large castles. This style later spread to northern England and Ireland.

In North Wales, King Edward I built many strong castles after defeating the Welsh in the 1270s. By the 14th century, castles combined strong defenses with fancy living spaces and beautiful gardens.

Many royal and baron castles were later left to fall apart. By the 15th century, only a few were kept for defense. Some castles in England and Scotland were turned into grand Renaissance palaces. These hosted huge parties and showed off amazing architecture. But only kings and the richest lords could afford such places.

Gunpowder weapons were used to defend castles from the late 14th century. However, by the 16th century, it was clear that cannons could also be used to attack castles if they could be moved close enough. Coastal castles around Britain and Ireland improved their defenses against these new threats. But investment in castles went down again by the end of the 16th century.

Even so, during the civil wars in the 1640s and 1650s, castles were very important in England. Old medieval defenses were quickly updated, and many castles successfully survived several sieges. In Ireland, Oliver Cromwell brought heavy cannons in 1649, which quickly made castles less useful in the war. In Scotland, the popular tower houses were not good for defending against civil war cannons, though big castles like Edinburgh Castle fought hard. After the war, many castles were damaged on purpose to stop them from being used again.

Military use of castles quickly decreased after this. Some were still used by soldiers in Scotland and at important border spots for many years, even during the Second World War. Other castles became county jails until laws in the 19th century closed most of them. For a while in the early 1700s, castles were not popular. People preferred Palladian architecture (a classical style). But then castles became important again in England, Wales, and Scotland. Many were "improved" in the 18th and 19th centuries.

These changes led to concerns about protecting castles. Today, castles across Britain and Ireland are protected by laws. They are mostly used as tourist attractions and are a big part of the national heritage industry. Historians and archaeologists are still learning more about British castles. Recent debates have even questioned how we understand their original building and use.

Contents

Norman Invasion and Early Castles

Before the Normans: Anglo-Saxon Forts

The word "castle" comes from the Latin word castellum. It means a strong, private home for a lord or noble. Most castles in Britain and Ireland appeared after the Norman invasion in 1066. Before the Normans, the Anglo-Saxons built fortified places called burhs. These were often large, walled towns, not private castles. Rural burhs were smaller, with a wooden hall and a wall. They were more for ceremonies than strong defense.

However, a few castles were built in England in the 1050s, likely by Norman knights working for Edward the Confessor. These included Hereford, Clavering, and Dover.

The Norman Invasion and Castle Building

William, the Duke of Normandy, invaded England in 1066. One of his first acts was to build Hastings Castle to protect his supplies. After winning the battle of Hastings, the Normans built castles in three stages.

First, the new king built royal castles in key places. These castles helped control England's towns, cities, and important roads. Examples include Cambridge, Lincoln, and York. Many of these urban castles were built in towns that had Anglo-Saxon mints (where coins were made). Building them often meant tearing down local houses. In Lincoln, 166 houses were destroyed! Some castles were built on top of important local buildings to show the new Norman rulers were in charge.

The second and third stages of castle building were done by powerful lords (magnates) and then by smaller knights on their new lands. Where castles were built depended on how the king divided the conquered lands. In some areas, like Sussex and Chester, lords' castles were close together. This was to protect routes to Normandy or the Welsh border. But in most of England, castles were spread out. As the Normans moved into South Wales, they built castles in valleys, using larger castles as bases.

Norman castle building in England and Wales didn't follow a big plan. It depended on local needs, like military factors or existing land layouts. Castles were often placed along old Roman roads to control travel and connect estates. Many were near river ports or at river mouths on the coast. Some groups of castles worked together for defense, like those around Gloucester. Fewer castles were built in East Anglia because it was more peaceful and had fewer workers.

Not all castles were used at the same time. Some were built during the invasion and then left. Experts think between 500 and 600 castles were in use at any one time after the conquest.

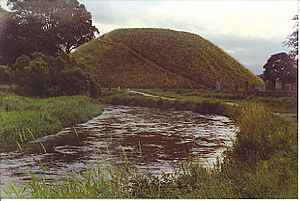

Castle Architecture: Motte and Bailey

Norman castles in England and Wales varied in size and shape. A popular type was the motte and bailey. This had a large earth mound (the motte) with a wooden tower on top, and a wider fenced area (the bailey) next to it. Stafford Castle is a good example. Another common design was the ringwork, a circular or oval earth bank topped with a wooden wall. Folkestone Castle is a Norman ringwork. About 80% of Norman castles were motte and bailey. Ringworks were popular in areas with shallow soil, as they were easier to build there.

The White Tower in London and Colchester Castle were the only stone castles built right after the conquest. Both had the classic square Norman keep. They were built in the Romanesque style to impress people and offer protection. In Wales, the first Norman castles were mostly wood, except for Chepstow Castle. Chepstow used materials from a nearby Roman town to look grand and ancient.

The size of castles depended on the land, the builder's choices, and available resources. Larger earthworks, especially mottes, needed many more workers. So, they were usually built by the king or the most powerful lords. Motte and bailey and ring-work castles took a lot of effort but needed few skilled workers. This meant they could be built quickly, often in one season, using local workers. Each castle was unique; some had two baileys, some ringworks had extra towers, and some ringworks were later turned into motte-and-bailey castles.

Castles in the 12th Century

Castle Life and Economy

In England, castles were either owned by the king (royal castles) or by Anglo-Norman lords (baronial castles). Royal castles were seen as the "bones of the kingdom." Many royal castles, like Winchester Castle, were also "shrieval" castles. This meant they were the main office for a county's royal sheriff, who made sure royal laws were followed.

Some royal castles were connected to forests and other important resources. Royal forests had special laws and provided the king with hunting grounds, materials, and money. Castles like Peveril Castle (for lead mining) and St Briavels (for the Forest of Dean) helped enforce these laws and store goods. In the southwest, castles like Restormel Castle managed local mining courts.

Baronial castles varied in size. The main stronghold of a lord was called a caput. These were usually bigger and stronger. The king could still use any castle in the kingdom if there was a threat. He also had to give permission to build new castles, called a license to crenellate. Even bishops could build or control castles, like Devizes Castle.

In the 12th century, a system called castle-guard started. Land was given to local lords if they provided knights or soldiers to defend a specific castle. At Dover Castle, this was so organized that certain castle towers were named after families who owed castle-guard duty.

Castles were also closely linked to the lands around them. Many castles, both royal and baronial, had deer parks or hunting grounds. These were often managed for hunting.

The Anarchy: A Time of Civil War

A civil war happened in England between 1139 and 1153. This was a difficult time when King Stephen and the Empress Matilda fought for power. There weren't many big battles. Instead, the fighting involved raids and sieges to control important castles.

During this "Castle War," both sides tried to win by taking castles. They used basic stone-throwing machines like ballistae and mangonels, along with siege towers and mining (digging tunnels under walls). They also tried blockades or direct attacks. Stephen tried to take Wallingford Castle, and Geoffrey de Mandeville tried to seize East Anglia by taking Cambridge Castle.

Both sides built many new castles during the war. Matilda's supporters built castles in the southwest, usually motte and bailey designs. Stephen built a chain of castles around Cambridge. Many of these were called "adulterine" (unauthorized) because they were built without royal permission. Some people at the time were worried about this. One writer said 1,115 such castles were built, though this was probably too high.

Another feature was "counter-castles." These were simple castles built during a siege, near the main target. They were usually motte and bailey or ringwork designs, about 200-300 yards away. They could be used to fire siege weapons or as bases to control the area. Most were destroyed after use, but some earthworks, like Jew's Mount outside Oxford Castle, still exist.

When Matilda's son, Henry II, became king, he wanted to destroy these unauthorized castles. It's not clear how successful he was. Many of the new castles were temporary. About 56% of castles built during Stephen's reign have "completely vanished."

Castles Spread to Scotland, Wales, and Ireland

Castles appeared in Scotland as the king gained more power in the 12th century. Before the 1120s, there's little proof of castles in Scotland. King David I wanted to expand royal power and modernize Scotland's military, so he brought in castles. He encouraged Norman and French nobles to settle in Scotland. They introduced a feudal system of land ownership and used castles to control the lowlands. The region of Galloway, which had resisted David's rule, was a key area for this. Scottish castles were mostly wooden motte-and-bailey designs, ranging from large ones like the Bass of Inverurie to smaller ones like Balmaclellan. Castles in Scotland were more about "establishing a governing system" than just conquest.

The Norman expansion into Wales slowed in the 12th century, but it was still a threat to Welsh rulers. In response, Welsh princes began building their own castles, usually made of wood. This might have started around 1111. These wooden castles were as good as Norman ones, and it can be hard to tell who built some sites just from the ruins. By the end of the 12th century, Welsh rulers started building stone castles, especially in North Wales.

Ireland was ruled by native kings until the 12th century, mostly without castles. There were Irish fortifications called ráths, which were ringforts, but they are not usually considered castles. The kings of Connacht built fortifications from 1124 called caistel or caislen, meaning castle. Experts still debate how much these looked like European castles.

The Norman invasion of Ireland began between 1166 and 1171. Anglo-Norman lords quickly took over southern and eastern Ireland. Their fast success was due to their economic and military advantages. Castles helped them control the new lands. The new lords quickly built castles, many of them motte-and-bailey designs. In Louth, at least 23 were built. Other castles, like Trim and Carrickfergus, were built in stone as main centers for powerful lords. These stone castles weren't just for defense; they also showed the lords' importance and provided space for managing the new territories. Unlike in Wales, Irish lords didn't build many of their own castles during this time.

Castles in the 13th and 14th Centuries

Life and Changes in Castles

From the 12th century onwards, royal castles became important storehouses for many goods. These included food, drinks, weapons, and raw materials. Castles like Southampton, Winchester, and the Tower of London were used to store and distribute royal wines. English royal castles also became jails. By 1166, royal sheriffs had to set up their own jails, and county jails were placed in all royal castles. Conditions in these jails were often very bad, with common complaints of poor treatment.

Baronial castles in England changed due to economic shifts. In the 13th and 14th centuries, rich lords became even richer, but there were fewer of them. Also, it cost more to keep and staff a modern castle. So, even though there were about 400 castles in England in 1216, the number decreased. Richer lords often let some castles fall apart to focus their money on others. The castle-guard system, where land was given for castle defense, slowly ended in England, replaced by money payments.

The remaining English castles became much more comfortable. Their insides were often painted and decorated with tapestries, which nobles carried with them as they traveled. More garderobes (toilets) were built inside castles. In richer castles, floors could be tiled, and windows had glass, allowing for window seats for reading. Food could be brought from far away; fish came to Okehampton Castle from the sea, about 25 miles away. Venison (deer meat) was the most common food, especially in castles with large parks.

By the late 13th century, some castles were built within carefully "designed landscapes." These might include a small, enclosed garden (a herber) with orchards and ponds, and a larger outer area with more ponds and fancy buildings. A gloriette, a set of small rooms, might be built in the castle to enjoy the view. At Leeds Castle, the redesigned castle in the 1280s was set in a large water garden. At Ravensworth in the late 14th century, an artificial lake and park made a beautiful entrance.

Welsh Castles and Edward I's Strongholds

During the 13th century, native Welsh princes built several stone castles. These varied from smaller forts like Dinas Emrys to larger ones like Dinefwr and Castell y Bere. Welsh castles often used high, rocky mountain sites for defense, with irregular shapes to fit the land. Most had deep ditches cut from rock. They usually had a short keep for living and distinctive D-shaped towers along the walls. Their gatehouses were weaker than Norman ones, with few portcullises or spiral staircases. The stonework was also generally not as good. Later Welsh castles, built in the 1260s, looked more like Norman designs, with round towers and twin-towered gatehouses.

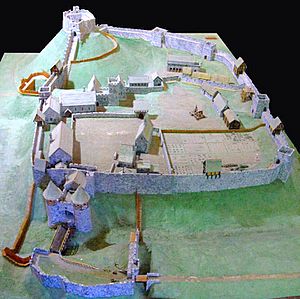

In 1277, King Edward I launched a final invasion of North Wales. He wanted to rule the region permanently. As part of this, he ordered eight new castles to be built: Aberystwyth, Builth, Beaumaris, Conwy, Caernarfon, Flint, Harlech, and Rhuddlan Castle. These are considered some of the best medieval military buildings in England and Wales. They had strong towers along the walls, many firing points, and very well-defended barbicans (outer defenses). The castles also had fancy living spaces for the king. Edward also built new English towns, and some castles were designed to work with the town walls for defense.

James of Saint George, a famous architect from Savoy, likely designed most of these castles. They were very expensive to build. Workers, masons, carpenters, and materials had to be brought from all over England. The total cost was at least £80,000, which was four times the usual royal spending on castles.

Edwardian castles also sent strong messages. For example, Caernarfon was decorated with carved eagles and had polygonal towers and striped stone, like the grand walls of Constantinople. This was meant to show imperial power. The castle's location near an old Roman fort was also important. Its elaborate gatehouse, with five sets of doors and six portcullises, was designed to impress visitors and remind them of King Arthur's legendary castles.

Palace-Fortresses: Luxury and Defense Combined

In the mid-13th century, King Henry III started redesigning his favorite castles, like Winchester and Windsor. He added larger halls, grander chapels, glass windows, and painted walls. This began a trend of building grand castles for fancy, elite living. Earlier keeps had one main hall, with the owner's family living on an upper floor for privacy. By the 14th century, nobles traveled less but brought bigger households and entertained more guests.

Castles like Goodrich were redesigned in the 1320s for more privacy and comfort, while still being strong defensively. This influenced later changes at Berkeley Castle. By the time Bolton Castle was built in the 1380s, it could hold up to eight different noble families, each with their own rooms. Royal castles like Beaumaris Castle, though built for defense, could hold up to eleven households.

Kings and the wealthiest lords could afford to turn castles into palace-fortresses. Edward III spent £51,000 on renovating Windsor Castle, which was more than one and a half times his usual yearly income. The result was a "great and unified palace" that looked grand but wasn't truly defensive. The rich John of Gaunt redesigned Kenilworth Castle. This work also focused on a unified, rectangular design, separating service areas from lavish living spaces. By the end of the 14th century, a unique English perpendicular style of architecture had appeared.

In southern England, new wealthy families built private castles. These castles used older military designs but weren't meant for serious defense. They were influenced by French designs, with rectangular shapes, corner towers, gatehouses, and moats. The walls enclosed a comfortable courtyard, similar to an unfortified manor house. Bodiam Castle, built in the 1380s, had a moat, towers, and gunports. But it was mainly for show and luxurious living, reminding people of Edward I's great castle at Beaumaris.

In northern England, improved security on the Scottish border and the rise of powerful families like the Percies led to more castle building in the late 14th century. Palace-fortresses like Raby, Bolton, and Warkworth Castle combined the southern quadrangular style with very large towers or keeps, creating a unique northern style. These castles, built by major noble families, were even more luxurious than those in the south. They marked a "second peak of castle building in England and Wales."

The Arrival of Gunpowder Weapons

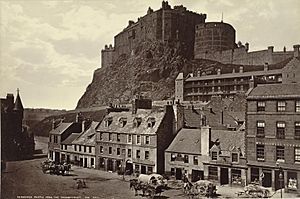

Early gunpowder weapons arrived in England around the 1320s and in Scotland by the 1330s. By the 1340s, the English king was regularly buying them. New cannons were installed in English castles by the 1360s and 1370s, and in Scottish castles by the 1380s. Cannons came in different sizes, from small hand cannons to large ones firing stone balls up to 7.6 inches. Medium-sized cannons (around 20 kg) were best for defending castles. However, King Richard II had 600-pound guns at the Tower of London, and the huge 15,366-pound Mons Meg bombard was at Edinburgh Castle.

Early cannons had limited range and were unreliable. Stone cannonballs were not very effective against stone castle walls. So, early cannons were most useful for defense, especially against foot soldiers or enemy siege machines. They could also be dangerous to their own side; James II of Scotland was killed in 1460 when his cannon exploded. Early cannons were expensive, so mostly kings used them, not nobles.

Cannons were first placed in English castles along the south coast. This was because French raids threatened the Channel ports, which were vital for English trade and military actions in Europe. Castles like Carisbrooke, Dover, and Portchester received cannons in the late 14th century. Small, circular "keyhole" gunports were built into the walls for these new weapons. Carisbrooke Castle was attacked by the French in 1377. The king responded by giving the castle cannons and a gunpowder mill in 1379. Some other English castles on the Welsh and Scottish borders were also equipped. The Tower of London and Pontefract Castle became supply centers for these new weapons. In Scotland, the first castle cannon was bought for Edinburgh in 1384, which also became a weapons storage place.

Castles in the 15th and 16th Centuries

The Decline of English Castles

By the 15th century, very few castles were well looked after. Many royal castles didn't get enough money for upkeep. Roofs leaked, stonework crumbled, and lead or wood was stolen. The king chose only a few royal castles to maintain, letting others decay. By the 15th century, only Windsor, Leeds, and Rockingham were kept as comfortable homes. Nottingham and York were important for royal power in the north. Even major forts like those in North Wales and border castles like Carlisle had less funding. Many royal castles continued to be used as county jails, often using the gatehouse as the main prison.

The number of powerful lords also decreased in the 15th century. This meant a smaller group of very wealthy lords, but most others had less money. Many baronial castles also fell into disrepair. Records from the 16th century describe castles as "sore decayed," their defenses "in ruine," or with good walls but "decayed" living spaces inside. English castles didn't play a major role in the Wars of the Roses (1455-1485). These wars were mostly fought in big battles between the Lancastrians and Yorkists.

Renaissance Palaces: Grand and Luxurious Castles

In the 15th and 16th centuries, a few British castles became even grander. They often used Renaissance ideas, which were popular in Europe. Large, solid tower keeps for private living, possibly inspired by French designs, appeared in the 14th century at Dudley and Warkworth. In the 15th century, this fashion spread with very expensive, French-style palace castles like Wardour, Tattershall, and Raglan Castle. In central and eastern England, castles started being built with brick, like Caister and Kirby Muxloe. In Scotland, the Holyrood Great Tower (1528-1532) followed this English tradition but added French influences. It became a very secure yet comfortable castle with cannons.

Scottish royal builders were leaders in using European Renaissance styles for castles. King James IV and King James V used special funds to strengthen their power across the kingdom. This included building grander castles like Linlithgow, usually by making existing forts bigger and better. These Scottish palace-castles used Italian Renaissance designs, especially the popular quadrangular court with stair-turrets at each corner. They used harling (a roughcast plaster) to give them a clean, Italian look. Later, castles like Falkland and Stirling Castle used French Renaissance designs. This change in style showed changing political friendships, as James V had a close alliance with France. These were the "earliest examples of coherent Renaissance design in Britain."

These changes also involved new social and cultural ideas. The old feudal system was breaking down, monasteries were destroyed, and the economy changed. This affected how castles were linked to the lands around them. Inside castles, the Renaissance brought the idea of public and private spaces. Castles now needed private rooms for the lord or guests, away from public view. Even though the elite in Britain and Ireland kept building castles in the old style, there was a growing understanding that homes were different from military forts built to resist gunpowder. Castles continued to be built to "invoke values seen as being under threat." For example, Kenilworth Castle was redesigned to look old and chivalrous, but it had private rooms, Italian loggias, and modern luxury.

Although noble households became slightly smaller in the 16th century, the number of guests at the biggest castle events kept growing. 2,000 people came to a feast at Cawood Castle in 1466. The Duke of Buckingham often entertained up to 519 people at Thornbury Castle. When Queen Elizabeth I visited Kenilworth in 1575, she brought 31 lords and 400 staff for an amazing 19-day visit. The owner, Leicester, entertained the Queen with shows, fireworks, bear baiting, plays, hunting, and huge banquets. With such grand living, finding more space in older castles became a big challenge in both England and Scotland.

Tower Houses: Strong Homes for Troubled Times

Tower houses were a common type of castle in Britain and Ireland in the late medieval period. Over 3,000 were built in Ireland, about 800 in Scotland, and over 250 in England. A tower house was usually a tall, square, stone building with crenellations (notches on the top of walls). Scottish and Ulster tower houses often had a barmkyn or bawn, which was a walled courtyard for keeping valuable animals safe. Many gateways had yetts, which were metal bar doors. Smaller tower houses in northern England and southern Scotland were called Peel towers. They were built on both sides of the border. It was once thought that Irish tower houses copied Scottish designs, but this isn't supported by evidence.

Tower houses were mainly for protection against small raiding parties, not against organized military attacks. They were "defensible rather than defensive." Some Scottish tower houses had gunports for heavier guns by the 16th century, but lighter gunpowder weapons like muskets were more common. Irish tower houses mostly used light handguns and often reused older arrowloops to save money.

Why were so many tower houses built? Two main reasons stand out. First, their construction seems linked to times of trouble and insecurity. In Scotland, King James IV's actions in 1494 led to a burst of castle building and more clan warfare. Wars with England in the 1540s also increased insecurity. Irish tower houses were built from the late 14th century as the countryside became unstable with many small lordships. King Henry VI even offered money to encourage their building to improve security. English tower houses were built along the dangerous border with Scotland.

Second, and surprisingly, tower houses also appeared during times of prosperity. One historian noted that in northern England and Scotland, "there is not a man amongst them of a better sort that hath not his little tower or pile." Many tower houses seem to have been built as much for status symbols as for defense. Along the English-Scottish borders, building patterns followed wealth: English lords built them in the early 15th century when northern England was rich, while Scots built them in the late 15th and early 16th centuries, when Scotland's economy was booming. In Ireland, the rise of tower houses in the 15th century matches the growth of cattle herding, which brought wealth to many smaller lords.

The Wars of the Three Kingdoms: Castles in Civil War

In 1603, James VI of Scotland became king of England, bringing peace between the two countries. The royal court moved to London, and building work on royal castles in Scotland mostly stopped. Investment in English castles, especially royal ones, dropped sharply. James sold many royal castles in England, including York and Southampton Castle. A royal inspection in 1609 found that the Edwardian castles of North Wales, like Conwy and Caernarfon, were "utterly decayed." A 1635 inspection found similar problems in English counties: many castles were falling apart. In 1642, a pamphlet said many English castles were "much decayed" and needed "much provision" for "warlike defense."

Those kept as private homes, like Arundel and Berkeley, were in better shape but not always defensible. Some, like Bolsover, were redesigned as modern homes in a Palladian style. Only a few coastal forts and castles, like Dover Castle, remained in good military condition.

In 1642, the English Civil War began between Parliament and Royalist supporters of King Charles I. The war spread to Ireland and Scotland. It was the first long conflict in Britain to use artillery and gunpowder. English castles were used in many ways. York Castle was a key part of city defenses. Rural castles like Goodrich were bases for raids. Larger castles, like Windsor, held prisoners or served as military headquarters.

During the war, castles were often quickly repaired. Existing defenses were fixed, and walls were "countermured" (backed with earth) to protect against cannons. Towers and keeps were filled with earth to make gun platforms, as at Carlisle and Oxford Castle. New earth defenses could be added, like at Cambridge. The costs could be high; work at Skipton Castle cost over £1000.

Sieges were a big part of the war, with over 300 happening, many involving castles. Castles played a much bigger military role than in medieval times. Artillery was essential in these sieges. There were more guns than in previous conflicts, sometimes one cannon for every nine defenders. The growth in artillery favored those who could afford these weapons. Cannons had improved by the 1640s but were not always decisive, as lighter cannons struggled to break earth and timber defenses, as seen at Corfe. Mortars, which could lob fire over tall walls, were very effective against castles, especially smaller ones with open courtyards, like Stirling Castle.

Heavy artillery eventually spread to the rest of Britain and Ireland. While Irish soldiers with European siege experience returned, it was Oliver Cromwell's arrival with his siege guns in 1649 that changed the war. No Irish castles could withstand these Parliamentary weapons, and most quickly surrendered. In 1650, Cromwell invaded Scotland, and his heavy artillery again proved decisive.

The Restoration: After the Wars

After the English Civil War, Parliament ordered many castles to be damaged or "slighted," especially in royal areas. This happened mostly between 1646 and 1651, with a peak in 1647. About 150 forts were slighted, including many castles. Slighting was expensive, so damage was usually done in the most cost-effective way, destroying only key walls. In some cases, the damage was almost total, like at Wallingford Castle or Pontefract Castle, which had been involved in three major sieges. The townspeople even asked for Pontefract to be destroyed to avoid future conflict.

By the time Charles II became king again in 1660, the major palace-fortresses in England that survived were in poor condition. Royal tastes were changing; people wanted different features in a successful castle. Palladian architecture was popular, which didn't fit well with medieval castle designs. Also, the fashionable French court needed many connected rooms, which was hard to fit into older buildings. A lack of money limited Charles II's efforts to remodel his castles. Only Windsor was fully completed during this time.

Many castles still had a defensive role. Castles in England, like Chepstow and York Castle, were repaired and had soldiers stationed there. As military technology advanced, upgrading older castles became very expensive. For example, converting York Castle in 1682 would have cost an estimated £30,000 (about £4 million today). Castles played a small role in the Glorious Revolution of 1688. However, some forts like Dover Castle were attacked by angry mobs. In Ireland, the sieges of King John's Castle in Limerick were part of the war's end.

In northern Britain, security problems continued in Scotland. Cromwell's forces had built new modern forts. But royal castles like Edinburgh, Dumbarton, and Stirling continued to be used as forts. Tower houses were built until the 1640s. After the Restoration, fortified tower houses went out of style. But because the Scottish economy was weak, many smaller castles were adapted as homes instead of being rebuilt. In Ireland, tower houses and castles were used until after the Glorious Revolution. Then, land ownership changed, and many Palladian country houses were built, often using wood from older, abandoned castles.

Castles in the 18th Century

Military and Government Uses

Some castles in Britain and Ireland continued to have minor military uses into the 18th century. Until 1745, a series of Jacobite risings (rebellions to restore the Stuart kings) threatened the Crown in Scotland. The last big rebellion was in 1745. Various royal castles were kept up as part of English border defenses, like Carlisle, or for security in Scotland, like Stirling Castle. Stirling withstood the Jacobite attack in 1745, though Carlisle was taken. The siege of Blair Castle in 1746 was the last castle siege in the British Isles. After the conflict, castles like Corgaff were used as barracks for soldiers in the Scottish Highlands. Some castles, like Portchester, held prisoners of war during the Napoleonic Wars at the end of the century. In Ireland, Dublin Castle was rebuilt and became the center of British power.

Many castles were still used as county jails, often run as private businesses. The gatehouse was usually the main prison building, as at Cambridge and St Briavels. In the 1770s, prison reformer John Howard surveyed prisons. His 1777 book, The State of the Prisons, showed how bad these castle jails were. Prisoners at Norwich Castle lived in a dungeon often covered by an inch of water. Oxford was "close and offensive." Worcester had so much "jail fever" (typhus) that the surgeon wouldn't enter. Howard's work changed public opinion against using old castles as jails.

Social and Cultural Uses

By the mid-18th century, medieval ruined castles became fashionable again. They were seen as an interesting contrast to the popular classical architecture and added a medieval charm to their owners. The ideal castle image by the 1750s included "broken, soft silhouettes and a decayed, rough appearance." Sometimes, the land around castles was changed to highlight the ruins, as at Henderskelfe Castle or "Capability" Brown's work at Wardour Castle. Ruins might also be repaired to look better, like at Harewood Castle. Old earth mounds (mottes) were sometimes used as bases for dramatic follies (buildings built just for decoration). New castle follies were also created, sometimes using old stonework, like at Conygar Tower.

At the same time, castles became tourist attractions. By the 1740s, Windsor Castle was an early tourist spot. Wealthy visitors could pay to enter and see curiosities. By the 1750s, the first guidebooks were sold. The first guidebook to Kenilworth Castle came out in 1777. By the 1780s and 1790s, visitors went as far as Chepstow, where a guide showed them around the ruins as part of the popular Wye Tour. In Scotland, Blair Castle and Stirling Castle became popular. Caernarfon in North Wales attracted many visitors, especially artists. Irish castles were less popular because tourists thought the country was behind the times.

The appreciation of castles grew. In the 1770s and 1780s, the idea of the "picturesque" ruin became popular, thanks to William Gilpin. Gilpin wrote about his travels, explaining what made a landscape "correctly picturesque." He believed such a landscape needed a building like a castle ruin to add "consequence." Paintings in this style showed castles as soft, distant shapes. Written accounts focused on first impressions rather than details. The ruins of Goodrich were very appealing to Gilpin. However, Conwy was too well preserved and not interesting enough for him. In contrast, the detailed work of antiquarians James Bentham and James Essex at the end of the century provided a lot of architectural detail on medieval castles.

Castles in the 19th Century

Military and Government Uses Decline

The military use of castles in Britain and Ireland continued to decrease. Some castles became military depots, like Carlisle Castle and Chester Castle. Carrickfergus Castle was updated with gunports for coastal defense after the Napoleonic Wars. Political unrest was a big issue in the early 19th century. The Chartist movement (a working-class political movement) led to ideas of refortifying the Tower of London in case of civil unrest. In Ireland, Dublin Castle became more important as Fenian groups pushed for independence.

The way local prisons, including those in castles, were run had been criticized since the 1770s. Pressure for reform grew in the 1850s and 1860s. Changes in laws about debt in 1869 largely ended imprisonment for unpaid debts, which removed the purpose of debtor's prisons in castles like St Briavels. Attempts to improve prison conditions failed, leading to prison reform in 1877. This law made British prisons national, including those at castles like York. Former owners were paid, but not if the facilities were so bad they needed complete rebuilding. This led to a big reduction in prisons, including famous castle prisons like Norwich. Over time, most remaining castle prisons closed.

Castles as Tourist Attractions and Homes

Many castles saw more visitors, helped by better transport and the growth of railways. The armories at the Tower of London opened to tourists in 1828, with 40,000 visitors in the first year. By 1858, this grew to over 100,000 a year. Attractions like Warwick Castle had 6,000 visitors in 1825-1826, many from nearby industrial towns. Victorian tourists paid six-pence to explore the ruins of Goodrich Castle. The railway system in Wales and the Marches greatly increased tourist flow to castles there. In Scotland, tours became popular, often starting at Edinburgh Castle and then going north by rail and steamer. Blair Castle remained popular, and others like Cawdor Castle became popular once railways reached them.

Buying and reading guidebooks became a key part of visiting castles. By the 1820s, visitors could buy a guidebook at Goodrich. The first guidebook to the Tower of London was published in 1841. Scottish castle guidebooks were known for long historical accounts, often using details from Romantic novels. Sir Walter Scott's novels Ivanhoe and Kenilworth helped create the popular Victorian image of a Gothic medieval castle. Scott's Scottish novels also made northern castles like Tantallon popular. Histories of Ireland began to emphasize castles' role in the rise of Protestantism and "British values," though tourism remained limited.

One result of this popularity was building replica castles. These were popular in the early 19th century and again later in the Victorian period. Design manuals showed how to create new Gothic castles. This led to buildings like Eastnor Castle (1815), the fake Norman castle of Penrhyn (1827-1837), and the imitation Edwardian castle of Goodrich Court (1828). Later Victorians built the Welsh Castell Coch in the 1880s as a fantasy Gothic castle. The last such replica, Castle Drogo, was built as late as 1911.

Another response was to improve existing castles, making their historical features fit a more unified architectural style, often called Gothic Revivalism. Many tried to restore or rebuild castles to create a consistent Gothic look, using real medieval details. Architect Anthony Salvin was famous for this, seen in his work at Alnwick and Windsor Castle. A similar trend is at Rothesay, where William Burges renovated the old castle for a more "authentic" design, influenced by French architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc. In Scotland, this led to the unique Scots Baronial Style architecture, which took French and traditional Scottish features and remade them in a grand style. This style was also popular in Ireland. Architects often "improved" existing castles; Floors Castle was transformed in 1838 with grand turrets. Similarly, the 16th-century tower house of Lauriston Castle became a Victorian "rambling medieval house." The style spread south, and architect Edward Blore added a Scots Baronial touch to his work at Windsor.

With all these changes, concerns grew by the mid-century about the threat to medieval buildings. In 1877, William Morris started the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings. Public pressure led to the Ancient Monuments Protection Act 1882, but this law focused on unoccupied prehistoric structures. Medieval buildings like castles were not protected, leaving no legal safeguards.

Castles in the 20th and 21st Centuries

1900–1945: Castles in Modern Conflicts

In the first half of the 20th century, some castles were maintained or brought back into military use. During the Irish War of Independence, Dublin Castle remained the center of British administration in Ireland until 1922. During the Second World War, the Tower of London held and executed suspected spies. It also briefly held Rudolf Hess, Adolf Hitler's deputy, in 1941. Edinburgh Castle was a prisoner of war camp. Windsor Castle was emptied of valuable royal treasures and used to protect the British royal family from the Blitz. Some coastal castles supported naval operations: Dover Castle's medieval forts were used for defenses across the Dover Strait. Pitreavie Castle in Scotland supported the Royal Navy, and Carrickfergus Castle in Ireland was a coastal defense base. Some castles, like Cambridge, were included in local defense plans in case of a German invasion. A few castles kept a military role after the war; Dover was a nuclear war command center into the 1950s, and Pitreavie was used by NATO until the 21st century.

Strong cultural interest in British castles continued. Sometimes, this led to problems as rich collectors bought and removed architectural features from castles for their own collections. This caused official concern. Notable cases included St Donat's Castle, bought by William Randolph Hearst in 1925 and decorated with medieval buildings moved from other sites. Also, at Hornby, many parts of the castle were sold to buyers in the United States. Because of these events, more laws were passed to protect castles. Acts of Parliament in 1900 and 1910 expanded earlier laws to include castles. An act in 1913 introduced preservation orders, and these powers were extended in 1931. After the Irish Civil War, the new Irish state also quickly strengthened laws to protect Irish national monuments.

Around the start of the century, there were major restoration projects on British castles. Before World War I, work was done at Chepstow, Bodiam, and Caernarfon. After the war, major state-funded restoration projects happened in the 1920s, including at Pembroke, Caerphilly, and Goodrich. This work usually involved clearing plants like ivy and removing damaged stonework. Moats at castles like Beaumaris were cleaned and refilled. Some castles, like Eilean Donan in Scotland, were largely rebuilt between the wars. The early UK film industry used castles as sets, starting with Ivanhoe filmed at Chepstow Castle in 1913.

1945–Present: Castles as Heritage and Tourism

After the Second World War, picturesque castle ruins became less popular. The focus shifted to restoring castles to be "meticulously cared for, with neat lawns and a highly regulated, visitor-friendly environment." However, rebuilding castles to look exactly as they did originally was not encouraged. As a result, the stonework of today's castles, used as tourist attractions, is usually in much better condition than in medieval times. Preserving the wider historical landscapes also became important. The UNESCO World Heritage Site program recognized several British castles, including Beaumaris, Caernarfon, Conwy, Harlech, Durham, and the Tower of London, as having special international cultural importance in the 1980s.

The largest group of English castles are now owned by English Heritage, created in 1983. The National Trust acquired many castle properties in England in the 1950s and is the second largest owner, followed by local authorities and a few private owners. Royal castles like the Tower of London and Windsor are owned by the nation. Similar organizations exist in Scotland, like the National Trust for Scotland (1931), and in Ireland, like An Taisce (1948), which works with the Irish Ministry of Works to maintain castles. New organizations like the Landmark Trust and the Irish Landmark Trust have also restored castles in Britain and Ireland.

Castles remain very popular attractions. In 2018, nearly 2.9 million people visited the Tower of London, 2.1 million visited Edinburgh Castle, and hundreds of thousands visited Leeds Castle and Dover Castle. Ireland, which had not fully used its castle heritage for tourism, began to encourage more tourists in the 1960s and 1970s. Irish castles are now a core part of the Irish tourist industry. British and Irish castles are also closely linked to the international film industry. Tourist visits often involve seeing not just a historic site, but also a location from a popular film.

Managing Britain's historic castles has sometimes been debated. Castles today are part of the heritage industry, where historic sites are presented as visitor attractions. Some experts criticize how these histories are constantly changed and how sites like the Tower of London are made too commercial. The challenge of managing these properties often requires practical decisions. For example, owners of smaller decaying castles used as private homes, like Picton Castle, have faced problems with damp. At the other end of the scale, the fire at Windsor Castle in 1992 led to a national debate about how to rebuild the burnt wing, how much modern design to include, and who should pay the £37 million cost. At Kenilworth, rebuilding the castle gardens in an Elizabethan style led to a lively academic debate about how to interpret historical evidence. Conservation trends have changed. Unlike the post-war approach, recent work at castles like Wigmore, acquired by English Heritage in 1995, tries to do as little as possible to the site.

Understanding Castle History

The earliest histories of British and Irish castles were written by John Leland in the 16th century. By the 19th century, studying castles became popular. Victorian historians believed British castles were built for military defense. They thought the mottes (earth mounds) across the countryside were built by the Romans or Celts.

The study of castles by historians and archaeologists grew a lot in the 20th century. In 1912, historian Ella Armitage published a book arguing that British castles were actually introduced by the Normans. Another historian, Alexander Thompson, also wrote about the military development of English castles through the Middle Ages. The Victoria County History of England began to document the country's castles in great detail, providing more information for historical analysis.

After World War II, the study of British castles was led by Arnold Taylor, R. Allen Brown, and D. J. Cathcart King. These experts used more and more archaeological evidence. The 1940s saw more excavations of motte and bailey castles, and the number of castle excavations doubled in the 1960s. With more castle sites threatened in cities, a public concern in 1972 about the Baynard's Castle site in London led to reforms and more funding for rescue archaeology (saving historical sites from destruction). Despite this, castle excavations decreased between 1974 and 1984, with work focusing on many small sites rather than a few large ones. The study of British castles still mainly focused on their military role, following the idea of improvements over time.

In the 1990s, there was a big change in how British castles were understood. A strong academic discussion about the history of Bodiam Castle led to a debate. It concluded that many castle features previously seen as military were actually built for status and political power. As historian Robert Liddiard put it, the old idea of "Norman militarism" as the main reason for castles was replaced by a model of "peaceable power." The next twenty years saw many major books on castle studies, looking at the social and political aspects of fortifications, and their role in the historical landscape. This "revisionist" (new way of looking at things) perspective is still the main idea in academic writing today.

Images for kids

-

The Norman square keep of Goodrich Castle in England, with the original first-floor doorway still visible above its later replacement

-

Dover Castle in England, built to a concentric design

-

A reconstruction of a trebuchet

-

A contemporary sketch of Lincoln Castle in England at the start of the 13th century, defended by a crossbowman

-

A reconstruction of Edward I's chambers at the Tower of London in England

-

Ravenscraig Castle in Scotland, showing its curved, low-profile fortifications designed to resist cannon fire

-

St Mawes Castle in England, one of Henry VIII's Device Forts

See also

In Spanish: Castillos de Gran Bretaña e Irlanda para niños

In Spanish: Castillos de Gran Bretaña e Irlanda para niños

| May Edward Chinn |

| Rebecca Cole |

| Alexa Canady |

| Dorothy Lavinia Brown |