Device Forts facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Device Forts |

|

|---|---|

| English and Welsh coasts | |

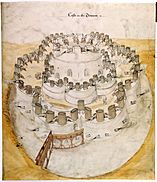

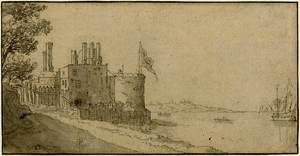

16th-century keep and gun platform at Pendennis Castle

|

|

| Type | Artillery castles, blockhouses and bulwarks |

| Site information | |

| Open to the public |

Most |

| Condition | Varied |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1539–47 |

| Built by | Henry VIII |

| In use | 16th–20th centuries |

| Materials | Stone, brick, earth |

| Events | English Civil War, Anglo-Dutch Wars, Napoleonic Wars, First and Second World Wars |

The Device Forts, also known as Henrician castles, were a group of artillery fortifications built to protect the coasts of England and Wales. They were ordered by Henry VIII between 1539 and 1547. Before this, local lords and communities usually handled coastal defences. However, the threat of invasion from France and Spain made King Henry VIII decide to build a strong new defence system.

These forts included large stone castles, smaller blockhouses, and earthwork defences called bulwarks. Some forts worked alone, while others were built to support each other. Building these forts was very expensive, costing about £376,000 at the time. Much of this money came from the King closing down monasteries a few years earlier.

These forts were armed with cannons to stop enemy ships from landing soldiers or attacking harbours. The first forts, built between 1539 and 1543, had round bastions and multiple levels for guns. They also kept some older medieval castle features. Later forts, built until 1547, used new designs with angled bastions, possibly inspired by ideas from Europe. The King appointed captains to lead small groups of professional gunners and soldiers at each fort. Local volunteer soldiers would join them if there was an emergency.

The Device Forts did not see much fighting before peace was made in 1546. Some forts were left to fall apart and were even closed down soon after they were built. When war with Spain began in 1569, Elizabeth I improved many of the remaining forts, especially during the attack of the Spanish Armada in 1588. By the end of the 1500s, the forts were becoming old-fashioned. Many were left to decay in the early 1600s.

Most of the forts were used during the English Civil War in the 1640s. They continued to protect England's coast against the Dutch after Charles II became king in 1660. Many forts fell into ruin again in the 1700s. However, they were updated and rearmed during the Napoleonic Wars until peace was declared in 1815.

In the 1800s, fears of a French invasion returned. New technologies like steamships and shell guns in the 1840s, and rifled cannon and iron-clad warships in the 1850s, changed warfare. This led to new money being spent on the Device Forts that were still useful. Others were closed down. By 1900, most of the Device Forts were too small for modern coastal defence. They were used again during the First and Second World Wars. However, by the 1950s, they were no longer needed and were permanently closed. Over time, Coastal erosion damaged or destroyed some sites. Many others were restored and opened to the public as tourist attractions.

Contents

- Building Henry VIII's Coastal Forts

- The Forts Through the Centuries

- Images for kids

- See also

Building Henry VIII's Coastal Forts

Why Henry VIII Built the Forts

England's Changing Defences

In the early 1500s, England's military defences changed a lot. Old medieval castles were not as useful because new cannons could easily destroy their stone walls. New castles were built, but they often looked more like symbols of power than strong forts. Many older castles were simply left to decay.

When Henry VII became king in 1485, he didn't worry much about invasions. He spent little on coastal defences. There were some small forts, mostly in the south, but they were not very big or strong.

His son, Henry VIII, became king in 1509. He was more involved in European wars, fighting France and Spain. But a full-scale invasion of England still seemed unlikely. The government usually left coastal defence to local communities. Henry VIII ordered reviews of the defences in 1513 and 1533, but not much was done.

The Threat of Invasion

In 1533, Henry VIII broke away from the Pope to end his marriage. This angered the Pope and King Charles V of Spain, who was his former wife's nephew. In 1538, France and Spain formed an alliance against Henry. The Pope encouraged them to attack England.

An invasion of England now seemed very likely. That summer, Henry personally checked some of his coastal defences. He was determined to make big, urgent improvements.

First Building Phase: 1539–1543

In 1539, Henry VIII ordered new defences to be built along England's coasts. This started a huge building project that lasted until 1547. The King's order was called a "device," which meant a detailed plan. This is why the forts became known as the "Device Forts."

The first orders were to build forts along the southern coast of England. They also improved defences in Calais and Guisnes, which were English towns in France. Experts were sent to inspect existing defences and suggest new fort locations.

In 1539, 30 new forts of different sizes were built. For example, the stone castles of Deal, Sandown, and Walmer were built in Kent. They protected an important anchorage called the Downs, where enemy ships could land. These castles were supported by four earthwork forts and a long ditch. Sandgate Castle guarded the route inland.

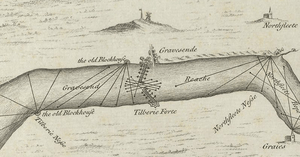

The Thames estuary, which was vital for trade, was protected by a network of blockhouses. These included forts at Gravesend, Milton, and Higham on one side, and West Tilbury and East Tilbury on the other. Camber Castle protected the ports of Rye and Winchelsea. Defences were also built in Harwich and around Dover.

Work also began on Calshot Castle and blockhouses at East and West Cowes on the Isle of Wight. These protected the Solent, which led to the port of Southampton. New castles at Portland and Sandsfoot protected the Portland Roads anchorage in Dorset. Two blockhouses were started to protect Milford Haven Waterway in Pembrokeshire.

In 1540, more work was ordered for Cornwall. Pendennis and St Mawes castles were built to protect the important Carrick Roads anchorage. In 1541, Hurst Castle and Netley Castle were built to further protect the Solent. The defences around Hull were upgraded in 1542 with a castle and two blockhouses. More forts were built in Essex in 1543.

The work was done very quickly. By the end of 1540, 24 sites were finished. Most of the rest were done by the end of 1543. However, by then, the alliance between France and Spain had broken, and the immediate threat of invasion was over.

Second Building Phase: 1544–1547

In 1543, Henry VIII joined Spain against France again. But in 1544, Spain and France made peace, leaving England open to a French invasion. Henry ordered more improvements to England's defences, especially along the south coast.

Work began on Southsea Castle in 1544 and Sandown Castle in 1545. Brownsea Castle in Dorset was started in 1545.

In July 1545, a French fleet arrived off the Solent. Henry's fleet retreated behind the forts. The French landed troops on the Isle of Wight, even taking the site of Sandown Castle, which was still being built. The French then moved along the coast, ending the immediate invasion threat. A peace treaty was signed in June 1546. By the time Henry died in 1547, a huge £376,000 had been spent on the Device Forts.

Who Designed and Built the Forts?

English engineers designed and built some of the Device Forts. John Rogers worked on the Hull defences. Sir Richard Lee may have helped build Sandown and Southsea. Sir Richard Morris and James Needham led the work along the Thames. The team from Hampton Court Palace also helped, ensuring high-quality construction.

King Henry VIII himself was very interested in the designs. He sometimes changed his engineers' plans. Southsea Castle was even described as being "of his Majesty's own device," meaning Henry played a personal role in its design. He was likely the main person guiding the whole project.

England also hired expert engineers from other countries, especially Italy. Italians were known for their advanced fortification designs. Stefan von Haschenperg from Moravia worked on Camber, Pendennis, Sandgate, and St Mawes. He tried to use Italian designs, but sometimes struggled because he didn't have much personal experience with them. Books from Europe also influenced the designs, showing new ways to build forts.

How the Forts Were Designed

The Device Forts were a huge and new building project for England. One historian called it "one of the largest construction programmes in Britain since the Romans." These forts were different from older medieval castles. Medieval castles were often homes and managed land. Henry's forts were built only for military purposes in important locations. They were plain and practical, not fancy.

The forts were placed to protect harbours and anchorages. They were designed to fire cannons at enemy ships and protect the gun crews. Some large forts, like those in Kent, could defend themselves from land attacks. Smaller blockhouses mainly focused on threats from the sea. While each fort was unique, they shared common features and a consistent style.

Larger forts like Deal or Camber were low and wide, with very thick walls to protect against enemy fire. They usually had a central keep, like older castles, with curved, circular bastions spreading out. The main guns were placed on multiple levels to hit targets at different distances. There were more gunports than actual guns. The walls had wide openings called embrasures, allowing guns to move and fire easily. The inside had space for gun operations and vents to remove gunpowder smoke. Moats often surrounded the forts to protect against land attacks. They also had medieval defence features like portcullises and reinforced doors.

These new forts were the most advanced in England at the time. They were good at focusing firepower on enemy ships. However, they had some weaknesses compared to forts in Europe. Their multiple gun levels made them tall targets. The curved bastions were also vulnerable to cannon fire.

Some of these problems were fixed in the second building phase from 1544. New ideas from Italy were used. The European approach used angled, "arrow-head" bastions that supported each other. Yarmouth Castle, finished by 1547, was the first English fort to use this new arrow-head design. However, not all forts in the second phase used these new Italian ideas.

How the Forts Were Paid For

The cost of building the forts varied a lot. A small blockhouse cost about £500, while a medium-sized castle like Sandgate or Portland cost about £5,000. The three castles in Kent (Deal, Sandown, Walmer) cost a total of £27,092.

Many officials managed each project, including a paymaster and an overseer. Some forts were paid for by local people. For example, St Catherine's Castle was reportedly paid for by the town and local gentry.

Most of the money went to the construction teams, called "crews." The number of workers changed, but teams were large. Sandgate Castle had an average of 640 men working daily in June 1540. Skilled workers earned 7 to 8 pence a day, and labourers earned 5 to 6 pence. It was hard to find enough workers, and some had to be forced to work. There were even strikes over low pay, but these were quickly stopped.

A lot of raw materials were needed, like stone, timber, and lead. Some materials came from nearby, but coal was shipped from northern England. Many prefabricated items came from London.

Most of the money for the first forts came from Henry VIII closing down monasteries a few years earlier. This also provided many building materials from the torn-down monastery buildings. For example, Netley Castle reused stones from an old abbey. By the second phase of building, most of this money was gone, and Henry had to borrow funds.

Life in the Forts: Garrisons and Weapons

Who Lived in the Forts?

The Device Forts had small groups of men called garrisons who lived and worked there. They maintained the buildings and cannons during peacetime. In a crisis, more soldiers and local volunteers would join them. The size of the garrisons varied. Camber Castle had 29 men, Walmer Castle had 18, and West Tilbury Blockhouse had only 9.

Ordinary soldiers lived in basic conditions, usually on the ground floor. The captains had nicer rooms, often on the upper levels of the keeps. Soldiers ate meat and fish, some of which they might have hunted or caught themselves.

Life in the forts was often "tedious" and "isolated." Soldiers had to provide their own handguns and could be fined if they didn't. There were only about 200 gunners in England in the 1540s. They were important specialists, and people saw them as mysterious and dangerous.

In 1540, a captain earned 1 or 2 shillings a day. His deputy earned 8 pence, porters 8 pence, and soldiers and gunners 6 pence each. That year, 2,220 men were paid, costing the King £2,208. While the King usually paid the garrisons, some local communities also helped. For example, the town of Brownsea provided 6 men for its fort.

What Weapons Did They Use?

The cannons in the Device Forts belonged to the King. They were managed from the Tower of London, which moved them between forts as needed. This often led to complaints from the local captains. Records show the number of guns at each fort. In the late 1540s, Hurst and Calshot had 26 and 36 guns, respectively. Portland only had 11. Some forts had more guns than their regular peacetime garrison could use.

Many types of cannons were used. There were heavy weapons like cannons and culverins, and smaller ones like sakers and falcons. Older guns were also used, but they were less effective. The heaviest guns were usually placed higher up in the fort, with smaller ones closer to the ground. The largest cannons could hit targets up to 2,743 metres (8,999 ft) away.

The forts had both brass and iron cannons. Brass guns fired faster and were safer, but they were expensive. In the 1530s, Henry started a new English gun-making industry. This industry could make cast-iron weapons. A breakthrough in 1543 greatly increased England's ability to make iron cannons. Few guns from this time survive. One iron gun, "Henry's Gun," was found at Hull in 1997 and is now in a museum.

Besides cannons, the forts also had weapons for soldiers. Handguns, like early matchlock arquebuses, were used for close defence. Many forts also had bows, arrows, and polearms like pikes and halberds. Longbows were still used by English armies in the 1540s. These weapons would have been used by local volunteers when they were called to action.

The Forts Through the Centuries

The 1500s: Decline and Revival

After Henry VIII died, there was a period of peace with France. Many new forts were allowed to fall apart. There wasn't much money for repairs, and the number of soldiers was reduced. East Cowes was abandoned around 1547. The earthwork defences along the Downs were damaged, and their guns were removed. They were officially taken out of service in 1550. In 1552, the Essex forts were closed, and some were pulled down.

The importance of south-east England decreased after peace with France in 1558. Military focus shifted to the Spanish threat in the south-west. When war broke out with Spain in 1569, improvements were made to Pendennis and St Mawes castles in Cornwall. Repairs were also done at Calshot, Camber, and Portland.

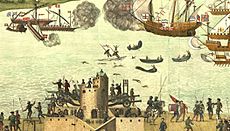

In 1588, the Spanish Armada sailed towards England. The Device Forts were prepared for battle. West Tilbury was brought back into use and supported by a quickly gathered army, which Queen Elizabeth I visited. Gravesend was improved, and some Essex forts were temporarily used again.

Even after the Armada was defeated, the Spanish threat continued. The castles in Kent remained ready for action. In 1596, a Spanish invasion fleet headed for Pendennis, but bad weather forced them back. Elizabeth I reviewed the defences and greatly expanded Pendennis with more modern bastions. However, by the end of the 1500s, most Device Forts were outdated compared to European standards.

The 1600s: Civil War and Restoration

English Civil War

When James I became king in 1603, England made peace with France and Spain. His government didn't pay much attention to coastal defences. Many Device Forts were neglected and fell into disrepair. Soldiers' wages were not paid. Hurst Castle, for example, couldn't stop Flemish ships from passing because it lacked ammunition. Some forts, like Camber Castle, were no longer needed due to changes in the coastline and were closed down.

The English Civil War began in 1642 between King Charles I's supporters and Parliament. Forts and cannons were very important in this war. Most Device Forts were used. Parliament quickly gained control of southern and eastern England. The blockhouses at Gravesend and Tilbury were used by Parliament to control access to London. The castles along the Kent coast were also taken by Parliament.

The Device Forts along the Solent also fell to Parliament early on. Calshot and Brownsea were garrisoned and strengthened. West Cowes and Yarmouth quickly surrendered. Southsea Castle was stormed by Parliamentary forces. Pendennis Castle, a Royalist stronghold, was besieged for a long time and finally surrendered in August 1646.

After the Civil War

Unlike many castles, the Device Forts were not deliberately destroyed by Parliament after the war. Many forts remained guarded by soldiers because there were fears of a Royalist invasion. Netley Castle was even brought back into use. Many forts, including Hull, Mersea, and Portland, were used to hold prisoners of war or political prisoners.

During the Anglo-Dutch Wars, forts like Deal were reinforced. Portland saw action during a naval battle. Some forts were closed, like Little Dennis Blockhouse and Mersea. Brownsea Castle was sold to private owners.

When Charles II became king in 1660, he reduced the size and pay of the garrisons. The Device Forts were still important for defence, but their design was old-fashioned. Deal continued to defend the Downs during the Dutch Wars. Hurst, Portland, and Sandgate remained guarded. However, Sandsfoot closed in 1665, and Netley was abandoned.

After a Dutch naval raid in 1667, Charles II made big improvements to his coastal defences. Pendennis, Southsea, and Yarmouth were updated. Tilbury was greatly expanded with new walls and moats. In the 1680s, Hull's castle and blockhouse were made part of a huge new fort called the Citadel.

Some Device Forts played a role in the Glorious Revolution of 1688. The people of Deal took over their castle to support William of Orange. Southsea Castle surrendered as the King's cause failed.

The 1700s and 1800s: Modernisation and Obsolescence

1700–1791: Changing Uses

The military importance of the Device Forts decreased in the 1700s. Some forts were changed to be more comfortable homes. Cowes Castle was partly rebuilt in 1716 to add living areas and gardens. Brownsea Castle became a country house. Walmer Castle became the home of the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports.

Many forts were criticized for having few soldiers and being in bad repair. Southsea Castle was said to have only "an old sergeant and three or four men who sell cakes and ale." Portland suffered from coastal erosion and was not repaired for many years. A 1714 survey found Pendennis Castle to be "in a very ruinous condition." French military experts in 1767 called Deal, Walmer, and Sandown "very old and little more than gun platforms." Mersea Fort and East Tilbury fell into ruin. However, Pendennis was updated in the 1730s, and Calshot in the 1770s.

1792–1849: Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars in the late 1700s and early 1800s led to some castles being re-manned and improved. Forts like Sandgate, Southsea, Hurst, and Pendennis, which were in important locations, were greatly modernized. Hurst was redesigned with heavier guns. Pendennis was equipped with up to 48 guns. Sandgate's keep was rebuilt as a Martello tower. New gun batteries were built at Deal, Sandown, and Tilbury. Fort Mersea was brought back into use.

Some Device Forts worked with volunteer units during the wars. Walmer Castle was used by William Pitt the Younger, who was Prime Minister, as a base for volunteer cavalry and armed fishing boats. Deal also had volunteer soldiers. Calshot stored ammunition for local Sea Fencibles. Pendennis trained a new volunteer artillery unit.

After the wars, some forts were used by the HM Coastguard to fight smuggling. Calshot was a good place for interception vessels. Sandown Castle in Kent was also used for anti-smuggling operations. Some forts became obsolete. Portland was disarmed and became a private house. Gravesend was demolished in 1844. Netley Castle ruins were turned into a Gothic-style house.

1850–1899: New Technologies

From the mid-1800s, new military technology constantly changed Britain's coastal defences. The invention of shell guns and steam ships created new risks. Fears of a French attack grew in the 1850s. Southsea Castle and St Mawes were extended with new gun batteries. Pendennis was re-equipped with heavier guns, and Hurst was greatly redeveloped.

New worries about France, along with rifled cannons and iron-clad warships, led to a review of defences in 1859. Sandgate was re-equipped with heavier guns. Hurst was fitted with huge batteries of heavy, iron-plated guns to fight fast enemy warships. Tilbury Blockhouse was destroyed to make way for heavier guns.

More concerns about France in the 1880s, combined with even more powerful naval guns and torpedo boats, led to another wave of modernization. An electronic minefield was laid at Carrick Roads, controlled from St Mawes and Pendennis. New, quick-firing guns were installed at Hurst. Calshot was brought back into service as a coastal fort. However, the original 16th-century parts of forts like Southsea and Calshot were too small for modern weapons. They were used for searchlights or range finding, and sometimes left to decay.

Some sites were no longer useful at all. West Cowes was closed in 1854 and became a club house. Sandown Castle in Kent was demolished from 1863 due to coastal erosion. Hull Citadel was demolished in 1864 to make way for docks. Yarmouth was closed in 1885 and became a coastguard station. Sandgate was sold off in 1888.

The 1900s and 2000s: End of Military Use

1900–1945: World Wars

By the early 1900s, most Device Forts were too small for modern guns and equipment. A 1905 review found that the guns at St Mawes were no longer needed. The castle was disarmed. In 1913, Calshot's naval guns were also deemed unnecessary, and the site became a seaplane station.

The War Office, which managed military buildings, was criticized for not taking care of historic sites. Yarmouth Castle was given to the Commissioners of Woods and Forests in 1901. Walmer and Deal castles were transferred to the Office of Works in 1904 and opened to visitors. Portland Castle continued to be used by the army, but with advice on repairs.

During the First World War, Pendennis's defences were strengthened. Southsea became part of the defence plan for the Solent. Calshot was a base for anti-submarine warfare. St Mawes and Portland were used as barracks. Walmer became a weekend retreat for the Prime Minister, Asquith.

In the Second World War, several Device Forts were used again. Pendennis, St Catherine's, St Mawes, and Walmer were equipped with naval guns. Calshot and Hurst were rearmed with naval guns and anti-aircraft defences. Sandsfoot was an anti-aircraft battery. Southsea was involved in Operation Grasp, which seized the French fleet in 1940. Others were used for support. Yarmouth was used by the military. Portland was used for housing and storage. West Cowes was a naval headquarters for part of the D-Day landings.

1946–Present: Public Access

After World War II, coastal defences became less important as nuclear weapons changed warfare. The remaining Device Forts were first guarded by reserve units, then closed as military sites. St Catherine's and Portland closed in the late 1940s. Hurst, Pendennis, and Yarmouth closed in the 1950s. Southsea closed in 1960, and Calshot in 1961.

Much restoration work was done. At Calshot, Deal, Hurst, Pendennis, Portland, St Catherine's, and Southsea, newer additions were removed to make the castles look like they did in earlier times. This led to more research into the forts' histories.

Many forts were opened to the public. Deal, Hurst, Pendennis, and Portland opened in the 1950s. Southsea opened in 1967. Calshot opened in the 1980s, and Camber in 1994. Sandsfoot reopened in 2012. Some forts were used for other purposes. Netley became a nursing home and then private flats. Brownsea became a hotel. Sandgate was restored in the 1970s as a private home.

By the 2000s, many Device Forts had been damaged or lost entirely due to coastal erosion. This problem has existed since the 1500s and still affects places like Hurst. East Cowes Castle and East Tilbury Fort are completely gone. East Blockhouse, Mersea, and Sandsfoot are badly damaged. Almost a third of Sandgate and most of St Andrews have been washed away. Other sites were demolished or simply eroded over time. Today, the remaining sites are protected by UK conservation laws.

Images for kids

-

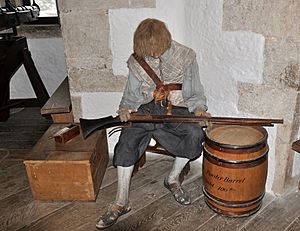

Reconstruction of a 16th-century cannon and gun crew at Pendennis Castle

See also

In Spanish: Device Forts para niños

In Spanish: Device Forts para niños