Hamites facts for kids

Hamites was a name used in the past for some groups of people in North Africa and the Horn of Africa. This term came from an old idea about dividing humanity into different races. This idea was developed by Europeans and was used to support colonialism (when one country takes control of another) and slavery. The word "Hamites" comes from the Book of Genesis in the Bible, referring to the descendants of Ham, who was one of Noah's sons.

The term "Hamitic" was used to describe certain languages like Berber, Cushitic, and Egyptian. These languages, along with Semitic languages, were once grouped together as "Hamito-Semitic." However, today, linguists no longer use the term "Hamitic" for languages. This is because these language groups don't form a single, exclusive family separate from other Afroasiatic languages. Instead, each is now seen as its own independent part of the larger Afroasiatic family.

Starting in the 1800s, scholars began to classify the Hamitic race as a subgroup of the Caucasian race. This group included non-Semitic people from North Africa and the Horn of Africa, like the Ancient Egyptians. According to the Hamitic theory, this "Hamitic race" was thought to be more advanced than the "Negroid" populations of Sub-Saharan Africa. In its most extreme form, this theory claimed that almost all important achievements in African history were made by "Hamites."

Since the 1960s, the Hamitic hypothesis and Hamitic theory, along with other ideas from "race science," have been proven wrong by scientists. They are no longer accepted.

Contents

History of the Idea

The "Curse of Ham"

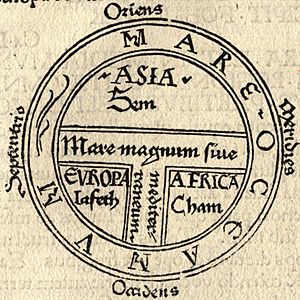

The word Hamitic first referred to people believed to be descendants of Ham, one of Noah's sons in the Bible. The Book of Genesis tells a story where Noah became drunk, and Ham disrespected him. When Noah woke up, he cursed Ham's youngest son, Canaan, saying his children would be "servants of servants." Ham had four sons: Canaan, Mizraim (who fathered the Egyptians), Cush (who fathered the Cushites), and Phut (who fathered the Libyans).

During the Middle Ages, some people believed Ham was the ancestor of all Africans. Some theologians (people who study religion) started to interpret Noah's curse on Canaan as causing visible racial features, especially dark skin, in all of Ham's descendants. Later, some traders and slave owners in the West and in Islamic lands used this idea of the "Curse of Ham" to try and justify enslaving Africans.

A big change in how Westerners viewed Africans happened after Napoleon's invasion of Egypt in 1798. This invasion brought attention to the amazing achievements of Ancient Egypt. These achievements were hard to explain if Africans were considered inferior or cursed. Because of this, some theologians in the 19th century pointed out that the biblical curse only applied to Canaan, Ham's youngest son, and not to Mizraim, the ancestor of the Egyptians.

Creating the "Hamitic Race"

After the Age of Enlightenment, many Western scholars were not satisfied with just the biblical stories to explain early human history. They started to create new theories that were not based on faith. These theories were developed at a time when many Western nations were still making money from enslaving Africans. Because of this, many books published about Egypt after Napoleon's trip seemed to try and prove that the Egyptians were not "Negroes." This helped to separate the advanced civilization of Ancient Egypt from what they wanted to see as an inferior race. Authors like William George Browne insisted that the Egyptians were white.

In the mid-1800s, the term Hamitic gained a new meaning in anthropology (the study of human societies and cultures). Scholars claimed they could identify a "Hamitic race" that was different from the "Negroid" populations of Sub-Saharan Africa. Richard Lepsius used the name Hamitic for languages that are now known as Berber, Cushitic, and Egyptian branches of the Afroasiatic family.

Some American anthropologists tried to scientifically prove that Egyptians were Caucasian, very different from the "inferior Negro." They did this by measuring thousands of human skulls. Samuel George Morton argued that the differences between races were too big to have come from one common ancestor. In his book Crania Aegyptiaca (1844), Morton studied over a hundred skulls from the Nile Valley. He concluded that ancient Egyptians were racially similar to Europeans. His findings helped create the American School of anthropology and influenced ideas that races had separate origins.

The Hamitic Hypothesis

The Hamitic hypothesis became very popular through the work of C. G. Seligman. In his book The Races of Africa (1930), he claimed that: "The civilizations of Africa are the civilizations of the Hamites... The incoming Hamites were pastoral Caucasians – arriving wave after wave – better armed as well as quicker witted than the dark agricultural Negroes."

Seligman believed that the "Negro race" was mostly unchanging and focused on farming. He thought that the traveling "pastoral Hamitic" people brought most of the advanced features found in central African cultures. These included metal working, irrigation (watering crops), and complex social structures. Even with criticism, Seligman kept his ideas in new editions of his book until the 1960s.

The idea of a "Hamite" racial and language group was strongly criticized as the concept of Hamitic languages was no longer used. In 1974, Christopher Ehret described the Hamitic hypothesis as the idea that "almost everything more un-'primitive', sophisticated or more elaborate in East Africa [was] brought by culturally and politically dominant Hamites." He called this a "monothematic" (one-topic) model that was "romantic, but unlikely" and "has been all but discarded, and rightly so." He argued that there were many different contacts and influences between various African peoples over time, which the "one-directional" Hamitic model ignored.

Subdivisions and Physical Traits

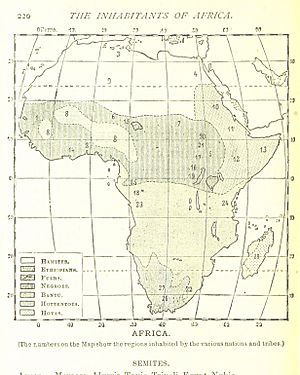

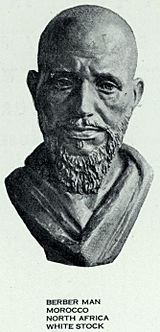

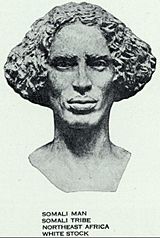

Giuseppe Sergi described the physical types of "Hamites." These descriptions were later used by writers like Carleton Coon and C. G. Seligman. In his book The Mediterranean Race (1901), Sergi wrote that there was a distinct "Hamitic" ancestral group. He divided it into two subgroups: the Western Hamites (including Berbers, Tibbu, Fula, and extinct Guanches) and the Eastern Hamites (including Ancient and Modern Egyptians, Nubians, Beja, Abyssinians, Galla, Danakil, Somalis, Masai, Bahima, and Watusi).

According to Coon, typical "Hamitic" physical traits were thought to include narrow facial features, a straight face, light to dark brown skin, wavy, curly, or straight hair, and a long to medium-long head shape.

"Hamiticised Negroes"

In the African Great Lakes region, Europeans based some of their migration theories on local stories from groups like the Tutsi and Hima. These groups claimed their founders were "white" migrants from the north (interpreted as the Horn of Africa or North Africa). They supposedly "lost" their original language, culture, and much of their physical appearance as they married local Bantus.

Explorer John Hanning Speke believed his travels showed a link between "civilized" North Africa and "primitive" central Africa. He argued that the "barbaric civilization" of the Ugandan Kingdom of Buganda came from a nomadic group of herders who had moved from the north and were related to the "Hamitic" Oromo of Ethiopia. Speke also tried to explain how the Empire of Kitara in the African Great Lakes region might have been started by a "Hamitic" ruling family. These ideas, presented as science, led some Europeans to claim that the Tutsi were superior to the Hutu. Even though both groups spoke Bantu languages, Speke thought the Tutsi had some "Hamitic" influence, partly because their facial features were narrower than those of the Hutu. Later writers agreed with Speke, arguing that the Tutsis had originally moved into the lake region as herders and became the dominant group. They supposedly lost their language as they adopted Bantu culture.

Seligman and other early scholars believed that in the African Great Lakes and parts of Central Africa, "Hamites" from North Africa and the Horn of Africa had mixed with local "Negro" women. This mixing supposedly created several "Hamiticised Negro" populations. These "Hamiticised Negroes" were divided into three groups based on language and how much "Hamitic" influence they had: the "Negro-Hamites" or "Half-Hamites" (like the Maasai, Nandi, and Turkana), the Nilotes (like the Shilluk and Nuer), and the Bantus (like the Hima and Tutsi).

European colonial powers in Africa used the Hamitic hypothesis to guide their policies in the 20th century. For example, in Rwanda, German and Belgian officials during the colonial period showed favoritism towards the Tutsis over the Hutu. Some scholars argue that this bias contributed to serious conflicts later on, including the 1994 Rwandan genocide.

See also

In Spanish: Lenguas camito-semíticas para niños

In Spanish: Lenguas camito-semíticas para niños

- Afroasiatic languages

- Generations of Noah

- Japhetites

- Semites

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |