Hector's dolphin facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Hector's dolphin |

|

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

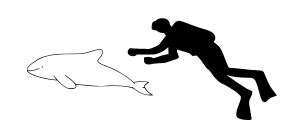

| Size compared to an average human | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Infraorder: | Cetacea |

| Family: | Delphinidae |

| Genus: | Cephalorhynchus |

| Species: |

C. hectori

|

| Binomial name | |

| Cephalorhynchus hectori Van Beneden, 1881

|

|

| Subspecies | |

|

|

|

|

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The Hector's dolphin (Cephalorhynchus hectori) is a small and special type of dolphin. It is one of only four dolphin species in the Cephalorhynchus group. What makes it truly unique is that it's the only cetacean (a group that includes whales, dolphins, and porpoises) that lives only in New Zealand.

There are two main kinds, or subspecies, of Hector's dolphin:

- The C. h. hectori, also known as the South Island Hector's dolphin, which is more common.

- The Māui dolphin (C. h. maui), which is very rare and lives off the West Coast of the North Island. It is in critical danger of disappearing forever.

Contents

Naming the Hector's Dolphin

The Hector's dolphin got its name from Sir James Hector (1834–1907). He was in charge of the Colonial Museum in Wellington, which is now the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Sir James Hector was the first person to study a Hector's dolphin specimen.

A Belgian scientist named Pierre-Joseph van Beneden officially described the species in 1881. The Māori people have their own names for these dolphins, including tutumairekurai, tupoupou, and popoto.

What Hector's Dolphins Look Like

Hector's dolphins are the smallest dolphin species in the world. Adult dolphins are usually about 1.2 to 1.6 meters (4 to 5 feet) long. They weigh between 40 and 60 kilograms (88 to 132 pounds). Female dolphins are a little bit longer than males, by about 5-7%.

They have a strong, chunky body shape and do not have a long, pointed nose like some other dolphins. Their most special feature is their rounded dorsal fin, which looks a bit like a Mickey Mouse ear.

Their bodies are mostly light grey. However, if you look closely, you'll see a mix of colors. Their back, sides, dorsal fin, flippers, and tail (flukes) are black. They have a black "mask" around their eyes that goes to their nose and back to their flippers. A dark, curved band crosses their head behind the blowhole. Their throat and belly are creamy white, with dark grey bands separating them. A white stripe also runs from their belly up each side, just below the dorsal fin.

When a Hector's dolphin calf is born, it is about 60 to 80 centimeters (2 to 2.6 feet) long. They weigh about 8 to 10 kilograms (18 to 22 pounds). Their colors are similar to adults, but the grey is a bit darker. Young calves also have faint stripes on their sides from being folded in the womb. These stripes fade away after about six months.

Life Cycle and Reproduction

Scientists have learned a lot about Hector's dolphins by studying them in the wild. They also learn from dolphins found on beaches or caught in fishing nets. Hector's dolphins can live for at least 22 years.

Male dolphins are ready to have babies when they are 6 to 9 years old. Females start having calves (baby dolphins) when they are 7 to 9 years old. A female dolphin usually has a calf every 2 to 3 years. This means she might have 4 to 7 calves in her whole life.

Calves are born during spring and summer. They stop drinking their mother's milk when they are about one year old. Sadly, about 36% of calves do not survive their first six months.

Because they have babies slowly, Hector's dolphin populations grow very slowly. Their population can only increase by about 3-7% each year.

Where Hector's Dolphins Live and What They Eat

Habitat

Hector's dolphins live in the murky coastal waters of New Zealand. They usually stay in waters shallower than 50 meters (164 feet) deep, but can be found in waters up to 100 meters (328 feet) deep.

They move closer to shore in spring and summer. Then, they move further out into deeper waters during autumn and winter. They often return to the same places each summer to find food. Scientists think their movements are linked to how clear the water is and where their prey (food) is found during different seasons.

Diet

Hector's dolphins eat many different kinds of small sea creatures. They usually choose prey that is less than 10 centimeters (4 inches) long. They also tend to avoid spiny fish. The biggest food item found in a Hector's dolphin's stomach was a red cod, weighing 500 grams (1.1 pounds) and 35 centimeters (14 inches) long.

Their diet includes fish that swim near the surface, fish that live in the middle of the water, squid, and creatures that live on the seafloor. Important foods for them include red cod, flatfish, ahuru, New Zealand sprat, arrow squid, and young giant stargazers.

Predators

Hector's dolphins can be hunted by larger sharks. Their remains have been found in the stomachs of broadnose sevengill sharks, great white sharks, and blue sharks. Killer whales (orcas), mako sharks, and bronze whaler sharks are also thought to hunt them.

Behaviour

Group Dynamics

Hector's dolphins usually form small groups of fewer than 5 individuals. The average group size is about 3.8 dolphins. These small groups are often made up of dolphins of the same sex. Larger groups are not as common.

You might also see "nursery groups." These are usually all-female groups with mothers and their young, typically fewer than 7 dolphins.

Hector's dolphins don't form very strong, lasting friendships with other individual dolphins. Instead, they form small groups based on their sex and age. For example, there are nursery groups, groups of young dolphins, and groups of adult males and females. These small groups tend to be separated by sex.

Echolocation

Hector's dolphins use high-frequency sounds, called echolocation clicks, to find their way around and hunt for food. They make quieter clicks than some other dolphins. This means they can only spot prey at about half the distance compared to a dolphin like the hourglass dolphin.

They have a very simple set of clicks and don't make many other sounds. When they are in larger groups, they might make more complex clicks.

Where They Live and How Many There Are

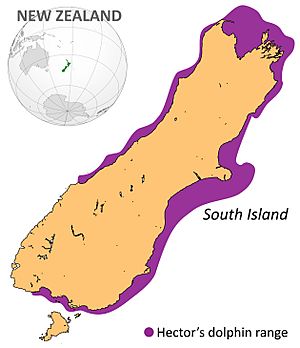

Hector's and Māui dolphins live only along the coast of New Zealand. Hector's dolphins are most common in areas with cloudy water around the South Island. They are found a lot off the East Coast and West Coast, especially around Banks Peninsula. Smaller groups live off the North Coast and South Coast, like at Te Waewae Bay.

Other smaller groups are scattered around the South Island in places like Cook Strait, Kaikoura, Catlins (including Porpoise Bay and Curio Bay), and the Otago coasts (like Karitane, Oamaru, Moeraki, Otago Harbour, and Blueskin Bay).

Māui dolphins live on the west coast of the North Island, between Maunganui Bluff and Whanganui.

Recent surveys have estimated that there are about 14,849 South Island Hector's dolphins. This is almost double what scientists thought before! This is mainly because more dolphins were found along the East Coast, further offshore than expected.

However, the Māui dolphin subspecies is still in great danger. The latest estimate is only about 63 Māui dolphins that are one year old or older.

Mixing of Dolphin Types

Sometimes, South Island Hector's dolphins are seen around the North Island, even as far as Bay of Plenty or Hawke's Bay. Scientists have found South Island Hector's dolphins living off the West Coast of the North Island, where Māui dolphins usually live.

For a long time, the deep waters of the Cook Strait were thought to keep the South Island Hector's and North Island Māui dolphins apart. This separation happened around 15,000 to 16,000 years ago, when the North and South Islands of New Zealand became separate.

Even though they are closely related, there is no proof yet that South Island Hector's dolphins and Māui dolphins have had babies together. If they did, it could help increase the number of dolphins in the Māui area and reduce problems from inbreeding (when closely related animals have babies). However, it could also mean that the Māui dolphin might eventually mix so much with the Hector's dolphin that it would no longer be seen as its own unique subspecies.

Threats to Hector's Dolphins

Fishing Dangers

Hector's and Māui dolphins often die because they get tangled or caught in fishing nets, especially gillnets and trawls. This usually causes them to suffocate. They can also get injured. Since the 1970s, gillnets have been made from thin, clear material that dolphins find hard to see. Hector's dolphins are sometimes attracted to fishing boats and might swim towards the nets, which can lead to them getting caught by accident.

In the past, fishing nets were the biggest danger to these dolphins. Scientists believe that many more dolphins have died in gillnets than have been reported. It's estimated that the current population is only about 30% of what it was in 1970, when there were around 50,000 dolphins.

Recent estimates (from 2014-2017) suggest that 19-93 South Island Hector's dolphins and 0-0.3 Māui dolphins die each year in commercial gillnets. For commercial trawls, the numbers are 0.2-26.6 Hector's dolphins and 0-0.05 Māui dolphins annually. While these numbers are lower for Māui dolphins now, fishing still poses a risk, especially to smaller groups of Hector's dolphins in certain areas.

Fishing Rules to Help Dolphins

New Zealand has created special marine protected areas (MPAs) to help Hector's dolphins. The first one was set up in 1988 at Banks Peninsula. In this area, commercial gill-netting was mostly stopped, and recreational gill-netting had rules for different seasons. Another MPA was created on the west coast of the North Island in 2003.

More protection was added in 2008. Gill-netting was banned in many areas around the South Island's east and south coasts. It was also banned further offshore on the South Island's west coast and extended on the North Island's west coast. Rules were also put in place for trawling in some of these areas. You can find more details on the Ministry of Fisheries website.

In 2008, five marine mammal sanctuaries were also created. These places help manage other dangers to dolphins, like mining and loud underwater surveys. More rules were added in 2012 and 2013 in Taranaki waters to protect Māui dolphins.

Experts from the International Whaling Commission and the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) have suggested even more protection. They recommend extending the protected areas for Māui dolphins further south and offshore. They also suggest protecting both Hector's and Māui dolphins from gill-net and trawl fishing from the shore out to where the water is 100 meters (328 feet) deep.

Loss of Genetic Diversity

Hector's dolphins often form small groups that are separated by sex. This can make it harder for males and females to find each other and have babies. When a population is very small and spread out, it can lead to a problem called the Allee effect. This means that low numbers can cause even lower birth rates, making the population shrink faster.

Also, Hector's dolphins tend to stay in the same feeding spots and don't travel much along the coast. This means there isn't much "gene flow" (the sharing of genes) between different groups. Over time, this can lead to a loss of genetic diversity, making the dolphins less healthy and less able to adapt to changes.

Studies of dolphin samples from the 1870s to today show how the population has declined. The loss of nearby dolphin groups due to fishing deaths has reduced gene flow. This has made the dolphin populations more separated and isolated, which can lead to inbreeding. The areas where they live have shrunk so much that gene flow between Māui dolphins and Hector's dolphins might not be possible anymore.

Some scientists think that if Hector's and Māui dolphins did have babies together, it could help the Māui dolphin population grow and reduce problems from inbreeding. However, others worry that too much mixing could cause the Māui dolphin to lose its unique identity as a subspecies.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Delfín de Héctor para niños

In Spanish: Delfín de Héctor para niños

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |