Hells Gate (British Columbia) facts for kids

Hells Gate is a very narrow part of British Columbia's Fraser River. It's located in the southern Fraser Canyon, near Boston Bar. Here, the tall rock walls of the Fraser River squeeze together, forcing the water through a passage only about 35 metres (115 ft) wide. It's also the name of the small area around this spot.

For hundreds of years, this narrow passage has been a great place for Indigenous communities to fish. Later, European settlers also came here in the summer to fish. The Fraser Canyon became a popular route for gold rush miners. They used it to reach areas further up the Fraser and Thompson rivers where gold could be found.

In the 1880s, the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) built a transcontinental railroad along the riverbank at Hells Gate. Then, in 1911, the Canadian Northern Railway (CNoR) started building a second track. In 1914, a huge rockslide happened because of the CNoR construction. It fell into the river at Hells Gate, blocking the path for Pacific salmon that needed to swim upstream to lay their eggs.

The water became much faster, making it very hard for salmon to pass. More salmon started appearing downstream below Hells Gate and in other tributary rivers and streams where they hadn't been before. Workers tried to clear the debris in the winter of 1914. By 1915, the river was declared clear. However, many scientists believed the river was permanently changed, and the salmon migration would always be affected by the slide.

The drop in Fraser salmon caused problems between the Government of Canada and the Indigenous peoples. Not only did the cleanup work stop them from fishing, but the government also set new fishing rules. For example, they limited fishing to four days a week to try and save the salmon. The slide and these new rules really hurt the Indigenous fishing economy.

To help, the Canadian and United States governments created the Pacific Salmon Convention (PSC) in 1937. This led to the International Pacific Salmon Fisheries Commission (IPSFC), now called the Pacific Salmon Commission. The IPSFC did a lot of research. Based on what they found, they suggested building special fishways to help salmon pass through Hells Gate. Building these fishways started in 1944.

This decision caused a big debate among fishing experts and researchers. They were divided, often along national lines. An American researcher, William Thompson, was criticized by Canadian zoologist William Ricker. Ricker said the IPSFC's research wasn't reliable and that fishways wouldn't save the Fraser salmon. Ricker thought Hells Gate wasn't the main problem for salmon. He believed too much commercial fishing was the real issue. He argued for strict rules on salmon fishing instead.

The fishways at Hells Gate became a popular tourist spot in the 1970s. Visitors can ride an airtram, eat at food places, enjoy observation decks, and learn about fisheries at an exhibit.

Contents

History of Hells Gate

The name Hells Gate comes from the journal of explorer Simon Fraser. In 1808, he described this narrow passage as "a place where no human should venture, for surely these are the gates of Hell."

Long before Simon Fraser arrived, Hells Gate was a gathering place for First Nations people. They settled there and fished for salmon. Old archaeological finds show that where and when Indigenous people lived in the Canyon matched the seasonal journeys of Pacific salmon.

Thousands of years ago, during the last deglaciation (when glaciers melted), ice formed in the river's basin. This created large reservoirs and new lakes, which were perfect places for salmon to lay eggs. During this time, salmon began to fill the Fraser River. They used Hells Gate to reach their spawning grounds upstream.

The passage at Hells Gate is very narrow, squeezed by two steep rock walls. The water flows incredibly fast here. This made it very hard for salmon to swim upstream. They would often stay close to the riverbanks or rest in calmer spots called back-eddies. Because of this, Hells Gate was an excellent place for Indigenous fishers to catch salmon. They would use long dip nets from rocks or wooden platforms. Fishing was so good that the Indigenous culture along the Fraser River was built on a "salmon economy."

After Simon Fraser mapped the river in the early 1800s, Hells Gate became an important route between the Pacific Ocean and the interior of what is now British Columbia. However, as Fraser first noted, it was almost impossible to travel safely by water through the narrow 115-foot opening at Hells Gate.

The Hells Gate Slide

By the 1850s, the Fraser Canyon changed from a First Nations and fur trade route to a busy path called the Cariboo Road. Gold rush miners used it to reach gold areas further up the Fraser River. In the 1880s, the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) built a new railway to connect Canada's provinces. This project involved building tracks on the west riverbank at Hells Gate. Some people believe rocks and debris from this construction narrowed the river and made it harder for salmon to pass, but there's no clear proof.

In early 1911, the Canadian Northern Railway (CNoR) started building a second railway along the south and east bank of the canyon. This was finished in about a year. As they carved into the canyon walls, a lot of rock and debris fell into the river at various places, including Hells Gate.

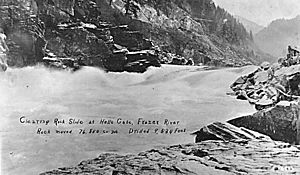

In early 1914, two years after the CNoR was finished, a huge rockslide fell into the river just above Hells Gate. This debris made the water 5 meters (about 16 feet) shallower and increased the water's velocity (speed) from five meters per second to 6.75 meters per second. Local people and later scientists noticed that the faster water seemed too strong for the salmon to swim through. This led to many salmon dying early and fewer young salmon (called fry) the next year.

To fix the changes at Hells Gate that were stopping salmon, tons of rocks and debris were removed from the river during the winter of 1914-1915. By early 1915, Hells Gate was declared clear. While government officials said the river was fully restored, many scientists still believe the slide permanently changed the river's environment.

How the Slide Affected Salmon

The rockslide at Hells Gate caused big changes that hurt salmon. The river became more turbulent (choppy) and dense. Salmon struggled to swim upstream, and many fish, tired from trying to get through Hells Gate, were swept back downstream. Daily changes in water levels also made it hard for some fish species to pass. One expert even compared the slide to "an enormous dam."

The effects of the slide were clear: fewer salmon were found upriver, while there was a constant supply of fish below Hells Gate. Salmon that couldn't swim upriver moved into other rivers and streams they hadn't used before. This led to more fish gathering several kilometers below Hells Gate. Pink salmon were affected more than sockeye because pinks are smaller and weaker swimmers. Salmon were forced to lay their eggs in new places, and many died without spawning or didn't produce many offspring because the new habitats weren't suitable.

In the short term, the salmon population went down. In the long term, these changes were even more serious. A "year's run once eliminated does not return." The decline in salmon was noticeable for about 14 years after the slide. Pacific salmon have a special four-year life cycle. For example, 1913 was a "big" year for salmon, and 1917 should have been too. However, salmon numbers were very low in 1917, showing a change in their normal cycle. The slide also destroyed many salmon from the Upper Adams River, where efforts to restore them had limited success.

Impacts on People and Politics

The changed river environment threatened the salmon, which then caused problems between the Canadian government and the Indigenous peoples of the area. The crisis at Hells Gate led to changes in Indigenous fishing rights in the canyon.

In July 1914, the Indigenous fishermen of the Nlaka'pamux people arrived for their traditional fishing season. But when they got to their usual fishing spot, they were stopped by the government's Public Works board. The board was clearing debris from the river after the slide. The Nlaka'pamux wrote to the Department of Indian Affairs about being treated unfairly and not being able to fish. A government official told them the slide had many causes, but the main goal was to protect the fish.

The Nlaka'pamux people blamed the Canadian Pacific Railway for the lack of fish. They argued that "all the fish [they] would catch in the year would not equal the number caught in one day by the white men at the mouth of the river." They had lost six days of important fishing and wanted the Department to pay them back. But the Department of Indian Affairs said they wouldn't do anything until an official report was written. This delay made the Nlaka'pamux even angrier, so they told their story to the newspapers, hoping for help. However, this didn't stop a federal Fisheries Officer from putting a new rule in place: fishing was limited to four days a week.

The Indigenous peoples felt that the government's cleanup efforts at Hells Gate were not good enough. In 1916, a group of Indigenous people offered ideas for improving the Gate's restoration, but government officials ignored them. Because of the new rules and fewer salmon, Indigenous communities faced local food shortages. Fishing became less important to their economy. They had to find other ways to get food, like going to the Skeena River system or hunting more moose.

Commercial fishing companies were less directly affected by the slide at first. They supported the government's actions to remove the blockages and to stop Indigenous people from fishing. The commercial fishery didn't feel the full impact of the slide until 1917. That year, the total catch was 6,883,401 sockeye, much lower than the 31,343,039 sockeye caught in 1913. Commercial fishing companies started to offer different types of fish products because of the slide's effects, while also trying to catch more fish. At the time, one person even said the Fraser fishery was "'practically a thing of the past.'"

The International Pacific Salmon Fisheries Commission (IPSFC) and Fishways

After many years of arguments over who should get how much of the Pacific Salmon catch, Canada and the United States agreed on a plan in 1937. It was called the Pacific Salmon Convention (PSC). This agreement created the International Pacific Salmon Fisheries Commission (IPSFC). Its job was to manage salmon and study Pacific salmon for eight years. The Commission would use this research to guide its work.

American researcher William Thompson led the IPSFC research team. They tagged fish at different places upstream to collect information. One of these places was Hells Gate. Scientists caught salmon along the banks, tagged them, took some scales for analysis, and then released them. In 1938, the IPSFC found what looked like a blockage of Fraser sockeye salmon at Hells Gate. Tagged fish were being caught more than once, held up behind the narrow river passage, and reappearing far downstream after being tagged. Based on this, Thompson decided to focus more on Hells Gate starting in 1939.

In 1941, something unusual happened with the Fraser salmon migration. In previous years, fish seemed to be blocked for about a week each spawning season. But this year, the blockage lasted for months, from July through October. Thompson used this chance to greatly increase tagging. He proudly said it was "'one of the most extensive tagging programs of its kind ever undertaken.'" By looking at old research, Thompson put his Hells Gate findings into a wider historical context. Using his own studies, he concluded that the rock blockage at Hells Gate was the main reason for the salmon decline in the Fraser River over many decades. To solve this problem, they started building several fishways in 1944.

A Big Disagreement

Canadian zoologist William Ricker, who had worked for the IPSFC, strongly disagreed with the decision to build fishways and with Thompson’s research. Ricker questioned Thompson’s main finding: that only 20% of fish could get through Hells Gate. He said this data was too selective and therefore unreliable. Ricker believed that the tagged fish might have been weaker than average, and that tagging itself could make it harder for a fish to swim through the fast water at Hells Gate. He argued that Thompson didn't properly address these issues, which could "completely invalidate the conclusion" that Hells Gate was a serious problem for salmon. Ricker also challenged other parts of Thompson’s research. He even suggested there was evidence (based on the number of male and female fish above and below Hells Gate) that no major blockage existed after the initial cleanup.

Ricker’s criticisms and Thompson’s replies caused a big debate among fisheries researchers. Many saw it as a national battle between Canadian and American scientists. Some thought Ricker was upset because Thompson and the IPSFC had found the Hells Gate blockage, which Ricker and the Canadian Biological Board should have discovered first. They saw Ricker's criticism as a result of this anger. Thompson also believed Ricker’s reasons were not scientific. He felt it was his duty to show this, so his response shifted the debate to the quality of Ricker and other Canadian fisheries researchers. Thompson argued that the Fisheries Research Board of Canada had either purposely or accidentally missed the fact that something was wrong at Hells Gate after the first cleanup. Either way, it was an insult to Canadian scientists.

Despite these criticisms, Thompson insisted that since fish numbers were getting better, the fishways were a success and clearly needed.

The two sides suggested different solutions. Thompson argued that environmental factors caused the salmon decline. He believed the best solution was to fix the damaged migration path. Ricker thought that too much fishing was the main threat to the Fraser salmon. He said it would be a "gamble" to rely only on fishways to save them. Instead, he argued for strict rules on salmon fishing. He also worried that conservationists and fishers might relax their efforts if they thought the fishways would solve everything, which would then threaten the salmon's survival.

Restoring the Salmon Run

By 1943, the IPSFC had found 37 things blocking the salmon run at Hells Gate. After getting a detailed plan from the IPSFC, both the Canadian and US governments approved building fishways at Hells Gate in 1944. By 1946, the fishways on both riverbanks were finished. They helped salmon pass easily when water levels were between 23 and 54 feet.

However, problems still existed at certain water levels. When water was very high (50–65 feet) or very low (11–17 feet), salmon still had trouble swimming upstream. To fix this, two high-level fishways were built. One on the right bank was finished in 1947, working for levels between 54 and 70 feet. Another on the left bank, completed in 1951, worked at the same levels. Still, some issues remained. The fishway on the left bank was made longer in 1965 to work at levels up to 92 feet. The last addition was in 1966, when sloping baffles were built on the left bank to help salmon pass below 24 feet.

The total cost of the fishways project was $1,470,333 in 1966, shared equally by the US and Canadian governments. This would be about $9,800,000 in 2010. Overall, the fishways were a success. The number of salmon swimming past Hells Gate had already increased five times in the short period between 1941 and 1945.

From 1946 to 1949, the IPSFC put strict rules on the Fraser River fishing industries. They delayed the start of the fishing season and ended it early. These strong strategies, which aimed for maximum protection, worked. The salmon population continued to grow into the early 1950s. Some people argued that these fishing restrictions helped the salmon population more than the expensive fishways did.

After the IPSFC's successful efforts, the Canadian government pushed for a pink salmon treaty. This treaty, signed in 1957, aimed to make sure pink salmon runs stayed healthy. It also stated that Canada and the US had to share the salmon run equally.

What Happened Next

Some people believe that building fishways at Hells Gate did more than just increase Fraser salmon. They claim it was also a way to make sure that future hydroelectric dams in the Fraser canyon would not be popular.

In 1971, Hells Gate and its fishways became a tourist attraction when the Hells Gate Airtram was completed. The tourist site now has food places, observation decks, and an educational fisheries exhibit. This exhibit shows short films about the area's history and a documentary about the salmon run.

Climate

Hells Gate has a Warm-summer Mediterranean climate (Köppen climate type Csb). It is in a climate zone that mixes the coastal oceanic climate with the drier inland semi-arid climate.

| Climate data for Hells Gate (Elevation: 122m) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 12.5 (54.5) |

13.9 (57.0) |

21.5 (70.7) |

28.9 (84.0) |

36.1 (97.0) |

38.3 (100.9) |

40.0 (104.0) |

40.6 (105.1) |

33.9 (93.0) |

25.6 (78.1) |

17.8 (64.0) |

17.2 (63.0) |

40.6 (105.1) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 0.5 (32.9) |

4.8 (40.6) |

9.2 (48.6) |

13.8 (56.8) |

19.0 (66.2) |

22.8 (73.0) |

26.4 (79.5) |

26.3 (79.3) |

20.1 (68.2) |

12.8 (55.0) |

5.2 (41.4) |

1.3 (34.3) |

13.5 (56.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −1.7 (28.9) |

2.0 (35.6) |

5.2 (41.4) |

9.0 (48.2) |

13.4 (56.1) |

17.1 (62.8) |

20.2 (68.4) |

20.3 (68.5) |

15.3 (59.5) |

9.4 (48.9) |

3.0 (37.4) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

9.4 (48.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −3.9 (25.0) |

−0.9 (30.4) |

1.1 (34.0) |

4.2 (39.6) |

7.8 (46.0) |

11.4 (52.5) |

14.0 (57.2) |

14.3 (57.7) |

10.4 (50.7) |

6.1 (43.0) |

0.7 (33.3) |

−2.8 (27.0) |

5.2 (41.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −24.4 (−11.9) |

−21.7 (−7.1) |

−20.6 (−5.1) |

−3.3 (26.1) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

3.9 (39.0) |

5.5 (41.9) |

6.1 (43.0) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

−13.5 (7.7) |

−24.0 (−11.2) |

−27.8 (−18.0) |

−27.8 (−18.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 186.4 (7.34) |

144.1 (5.67) |

117.4 (4.62) |

69.1 (2.72) |

44.4 (1.75) |

32.9 (1.30) |

24.9 (0.98) |

30.6 (1.20) |

62.6 (2.46) |

132.7 (5.22) |

182.8 (7.20) |

201.2 (7.92) |

1,229.1 (48.39) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 113.3 (4.46) |

116.8 (4.60) |

111.3 (4.38) |

68.9 (2.71) |

44.4 (1.75) |

32.9 (1.30) |

24.9 (0.98) |

30.6 (1.20) |

62.6 (2.46) |

132.5 (5.22) |

162.7 (6.41) |

153.6 (6.05) |

1,054.4 (41.51) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 73.1 (28.8) |

28.3 (11.1) |

6.1 (2.4) |

0.2 (0.1) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

1.2 (0.5) |

16.2 (6.4) |

46.4 (18.3) |

171.5 (67.5) |

| Source: Environment Canada (normals, 1961-1990) | |||||||||||||

Hells Gate Airtram

The Hells Gate Airtram starts at the parking lot of the Trans-Canada Highway. It takes visitors down to its lower station on the other side of the Fraser River. There, you'll find a pedestrian suspension bridge, an observation deck, a restaurant, a gift shop, and other fun tourist spots.

The airtram was built in 1970 by a Swiss company and opened on July 21, 1971. It has two cabins, and each can carry 25 people plus an attendant. Each cabin travels up and down its own track rope. The fastest speed is 5 meters per second (about 18 kilometers per hour or 984 feet per minute). The total length of the ride is 341 meters (1118 feet) on a slope. The horizontal distance between the stations is 303 meters (994 feet), and the height difference is 157 meters (515 feet). The average slope between the stations is 51%.

The main track ropes are 40mm thick. The rope that pulls the two cabins is 19mm thick, and its counter rope is 15mm thick. The track ropes are held firmly at the top station. At the bottom station, they are kept tight by two concrete blocks, each weighing 42 tons. These blocks can move up and down by 7.9 meters. The pulling rope and its counter rope are kept tight by a 3.5-ton weight, also at the bottom station. The motor can produce up to 140 horsepower (104 kW). The airtram can carry up to 530 passengers per hour in one direction.

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |