History of Bălți facts for kids

Bălți is the second largest city in Moldova. It is located in the northern part of the country. The city's history is closely linked to the historical region of Bessarabia.

Contents

Bălți in the Middle Ages

During the Middle Ages, Bălți was a market town. It first belonged to Soroca and later to the Iași county of the Principality of Moldova. Bălți was an important crossroads. Roads from Iași, Hotin, Soroca, and Orhei met there. It quickly became famous for its horse fair and also for selling cattle.

In 1469, Crimean Tatars led by Meñli I Giray attacked and burned Bălți. The invaders were later defeated in the Battle of Lipnic, about 100 km north. The city was rebuilt, but it took a long time. Over the years, Bălți also became a center for skilled workers. There were smiths, wheel makers, leather workers, and cart makers.

Bălți in the 1700s

In 1711, the Moldavian prince Dimitrie Cantemir invited the Russian tsar Peter the Great to Moldavia. Cantemir was a famous historian and scientist. He hoped to end the Ottoman rule over Moldavia. Moldavia had been a vassal state to the Ottomans since 1538. This meant it kept its own rule but had to pay a yearly tribute.

During this war, Bălți was a main headquarters for the Russian and Moldavian armies because of its location. The town was burned down again. Some say Nohai Tatars did it as revenge. Others say the retreating Russians burned it.

The city's growth in the 18th century was slow. This was because people had to deal with invasions from three armies: Ottoman, Russian, and Habsburg. These armies fought four major wars, stealing goods and demanding supplies from the people. Sometimes, each army set up its own government. They forced people to work for them and punished those who helped the other side. The last parts of serfdom were officially ended in Moldavia in 1749.

In 1766, Prince Alexandru Ghica divided the Bălți land into two parts. One part went to the Saint Spiridon monastery in Iaşi. The other went to the merchant brothers Alexandru, Constantin, and Iordache Panaiti. These brothers improved the area, settled farmers, and encouraged crafts and trade.

Moldavian leaders built a church in Bălți in 1785. That same year, the land around the city moved from Soroca county to Iaşi county. Bălți became the second largest place in the county.

Bălți in the 1800s

Becoming Part of the Russian Empire

In 1812, after a six-year war, the Treaty of Bucharest was signed. The Ottoman Empire gave the eastern half of Moldavia, including Bălți, to the Russian Empire. This new area was called Bessarabia. Bălți benefited from this change. Even though the city of Iaşi stayed on the west bank of the River Prut, most of Iaşi County was on the east bank. Bălți, with about 8,000 people, slowly became the main center of this area.

In 1818, Bălți officially became a city. A popular story says that Tsar Alexander I visited his new province. While in Bălți, he heard that his nephew, the future Alexander II of Russia, was born. Overjoyed, he made Bălți an official city and the administrative center of the county. In 1828, Bessarabia's counties were reduced from twelve to eight. Iaşi County remained, and in 1887, it was renamed Bălți County.

Growing and Changing

Under Russian rule, more people from different backgrounds moved to Bălți. People came from Austrian Galicia, Russian Podolia, and even Russia itself. Some new settlers were given land. Others sought religious freedom, as the western parts of the Russian Empire, especially Bessarabia, were more open to different religions and did not have serfdom.

Many Jews from Galicia (then part of the Habsburg Empire) settled in Bălți. By the end of the century, they became the largest group, and later, the majority. Before World War I, the Jewish community had over 10,000 people, making up to 70% of Bălți's population. Over time, 72 synagogues were built in the city.

By 1894, Bălți became a railway hub. It connected with Czernowitz, Hotin, Chişinău, Bender, Akkerman, and Izmail. The city was a regional center for collecting wheat and other crops. These were then sent by train to Odessa. Bălți also grew into a major trading center in Bessarabia, mainly for cattle. By the early 1900s, Bălți was an industrial city with strong trade and many small factories.

Bălți in the 20th Century (Before 1989)

World War I and Its Impact

When World War I started, most men aged 18 to 45 in the region joined the Russian army. They later formed Moldavian Soldiers' Committees, which became a strong political force. In late 1917, after the Russian Empire broke apart, Bessarabia elected its Sfatul Țării (National Diet). This group declared the Moldavian Democratic Republic in December 1917. They formed a government and then declared independence from Russia in January 1918. Finally, they united with the Kingdom of Romania in March 1918. Bălți was not directly affected by the fighting of World War I, apart from soldiers being recruited and moved through the city.

In May 1917, General Shcherbachov, the commander of Russian armies on the Romanian Front, allowed Moldavian soldiers to form their own units. These units were sent to all Bessarabian counties. Their numbers increased in September because Russian army deserters were causing violence and stealing. Two Cossack regiments stayed in Bălți county. A large group of 3,000 soldiers in Orhei also caused trouble, leading to widespread stealing and deaths in Bălți, Soroca, and Orhei counties. In December 1917, when the Moldavian Democratic Republic formed its armed forces, one of its first units was in Bălți. This unit was made of Moldavian soldiers and led by Captain Anatolie Popa. In March 1918, the Bălți Council of Landowners asked the Sfatul Țării to consider uniting with Romania, which soon happened.

Between the World Wars

Bălți's economy grew in the early 20th century, and the city became more diverse. Many buildings in Bălți were built during this time. In the 1920s, the main church office (Bishopric) moved from Hotin to Bălți. With the help of Visarion Puiu, construction began on the Bishopric Palace, which was finished in 1933. The Saint Constantine and Elena Cathedral was completed in 1932 and officially opened in 1933, with the Romanian royal family present.

According to the 1930 Romanian census, Bălți had 30,570 people. This included 14,229 Jews, 8,868 Romanians, 5,426 Russians, 981 Poles, and 1,066 people of other backgrounds. Most people were Christian Orthodox (14,400), followed by Jewish (14,250), and Roman Catholic (1,250). By 1940, the city's population reached nearly 40,000. About 45–46% were Jews, 29–30% were Romanians, and the rest were Ukrainians, Russians, Poles, and Germans.

Bălți During World War II

After the Soviet occupation of Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina in 1940, thousands of people from northern Bessarabia were seen as a threat to the Soviet government. These included teachers, doctors, office workers, and even wealthier farmers. They were gathered and sent in cattle cars to Siberia. Bălți, being a key railway link in the north, was a gathering point for this. The largest deportation happened on June 12–13, 1941. The local economy, with its many small factories and shops, was largely taken apart. Several factories and buildings were blown up.

From June 22 to July 26, 1941, the Romanian Army joined Operation München, an attack against the Red Army in Bessarabia. The city of Bălți was part of this battle. The goal was for the 14th Romanian Division to capture the city. Soviet units managed to stop them temporarily on July 4.

The main military actions took place between July 7 and 9, south of the city. Romanian regiments fought with Soviet cavalry. The Romanians were more comfortable on the ground than the German and Soviet units. They managed to overcome several Soviet strongholds. With artillery support, they attacked and forced Soviet forces to retreat, leaving much of their heavy weapons behind. On July 9, Romanian troops reached the Răut river and set up a position north of it, threatening to surround the Red Army in the city. The Red Army then quickly pulled out.

Reinhard Heydrich, a high-ranking German SS officer, flew several fighter missions from the Bălți-City Airport in July 1941. He was shot down over Ukraine and barely escaped capture.

After the Axis forces captured the city, a small German SS unit killed about 200 Jews in three days. Most of the 15,000 Jewish people in the city had managed to escape in the weeks before. Soviet authorities had helped them evacuate by train to Central Asia, mostly to Uzbekistan. Most of them survived and returned after the war, but their lives as refugees were very hard. In August 1941, about 1,300 Jews were left in Bălți. The pro-fascist government of Ion Antonescu decided to deport them. In September 1941, they were gathered into two ghettos near Bălți. After about 10 days, these ghettos were closed, and the roughly 11,000 Jews were quickly moved to a concentration camp. Two weeks later, this camp was also closed, and the Jews were sent to occupied Transnistria.

This process allowed their persecutors to take most of the Jews' belongings. It also kept the public from knowing what was truly happening to the Jews until it was too late. The Holocaust affected nearly 75,000 Bessarabian Jews, and many others. Less than one-third of the deported Jews survived.

Between February 27 and March 2, 1944, Soviet troops entered the city, pushing Romanian and German forces westward. In the summer of 1944, the Soviets created two POW camps in the city. These camps held up to 45,000 prisoners at a time. In total, about 55,000 people passed through these camps. They included Romanians, Germans, Italians, Hungarians, Poles, and Czechs. After the war, the camps were removed.

After the 1944 Soviet attack, thousands of people, including many educated individuals, fled to Romania. Like other places in Moldova, Bălți lost most of its educated people who became refugees. In the summer of 1944, the Red Army launched a major attack, defeating a large part of the German-Romanian forces. On August 23, 1944, Romania changed sides and joined the Allies for the rest of the war. After this successful attack, Moldavians of suitable age in the recaptured areas were drafted into the Soviet army. They were not released until 1946.

After World War II

In 1944, when the Soviet authorities returned, they continued to persecute people based on their politics and social class. People were deported from northern Moldova to Siberia, the northern Urals, the Russian Far East, and Kazakhstan. The largest postwar deportation, called "Operation South", happened on July 5–6, 1949. It included 185 families from Bălți and 161 families from its suburbs. About 12,000 Bessarabian families were rounded up and deported in this operation. (The city's population at the time was about 30,000.) Many young people were also sent to labor camps across the Soviet Union.

An anti-Soviet resistance group called "Sabia Dreptăţii" ("The Sword of Justice") was active in Bălți during the Stalinist era. It was found by the NKVD in 1947 at the Pedagogical Lycée in Bălți.

The war and the events that followed greatly affected the city. Many buildings were destroyed or damaged. A large part of the population was killed, deported, sent to labor camps or ghettos, starved, or fled and did not return. These losses affected all ethnic groups. The educated people from before the war almost completely disappeared.

During the 1940s and early 1950s, Bălți lost many people due to Stalinist actions (imprisonment and deportations), the Romanian deportation of Jews (the Holocaust), the war, the Soviet famine of 1946–1947, and people moving away.

After World War II, many people moved to Moldova from all over the USSR. This was to rebuild the country, develop industries, and set up Soviet government offices. In the 1980s, many Moldovans from the countryside moved to Bălți. By the late 1980s, most of Moldova's Jews had moved to Israel. By then, Russian and Ukrainian speakers made up 50% of the city's population, with Moldavian speakers making up the other 50%.

During Soviet times, Bălți had many different nationalities. Russian was the main public language. From 1940 to 1989, the city's population grew four times. This was due to newcomers from across the USSR and Moldovans moving from rural areas. The city became a major industrial center.

Bălți From 1989 to Today

During 1988 and 1989, a very active time in Moldova's recent history, Bălți was known as the "quiet city." Few public protests happened there, and none gathered more than 15,000 people. Most citizens, including Moldovans, did not support making Romanian the only official language of the country.

All local elections were won by candidates from the old Soviet government. City activities were done in both Russian and Moldovan. The city also supported Ukrainian language and culture, as about 25,000 citizens were Ukrainians.

After Moldova declared independence in 1991, strong national feelings grew. The economic crisis and job losses from the collapse of the USSR led to many people moving away. This, combined with a low birth rate, caused Bălți's population to drop by 23%. Russians and Ukrainians were the most affected groups, losing 45% and 30% of their 1989 numbers, respectively. The Moldovan population decreased by 15%. Many people from Bălți traveled for seasonal work or moved to Europe, Russia, the United States, and Israel.

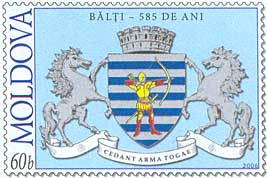

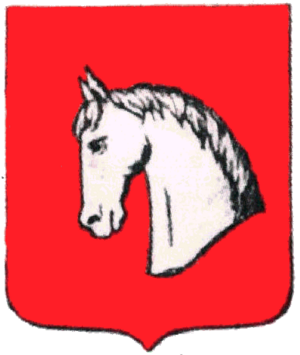

Despite these changes, Bălți's tradition of transport-related work continued. The city had several factories and repair shops for engines and cars. The city's old coat of arms, which featured a horse's head, was replaced with a new one showing two horses. Bălți also formed a partnership with the French city of Lyon.

In 1994, Bălți gained the status of a municipality.

|