Ottoman Bulgaria facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Ottoman Bulgaria

|

|

|---|---|

| 1396–1878 | |

|

|

| Common languages | Bulgarian |

| Religion | Sunni Islam (official, minority) Bulgarian Orthodox Church (majority) |

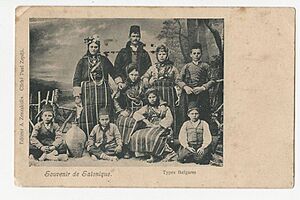

| Demonym(s) | Bulgarian |

| Government | |

| Beylerbey, Pasha, Agha, Dey | |

| History | |

| 1396 | |

| 1878 | |

| Today part of | Bulgaria |

The history of Ottoman Bulgaria covers almost 500 years. It started in the late 1300s when the Ottoman Empire took over smaller kingdoms from the weakening Second Bulgarian Empire. This period ended in the late 1800s when Bulgaria was freed from Ottoman rule. By the early 1900s, Bulgaria officially declared its independence.

A major event was the April Uprising of 1876 by Bulgarians, which was put down very harshly. This caused a lot of anger across Europe. It led to the Constantinople Conference, where powerful European countries suggested creating two self-governing Bulgarian areas. These areas would mostly follow the places where Bulgarians lived.

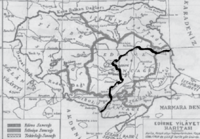

However, the conference failed. This led to the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878). After this war, a smaller Principality of Bulgaria was formed. It was a self-governing state, but still officially part of the Ottoman Empire. Later, in 1885, the Ottoman province of Eastern Rumelia joined with the Principality of Bulgaria peacefully.

Contents

How the Ottomans Ruled Bulgaria

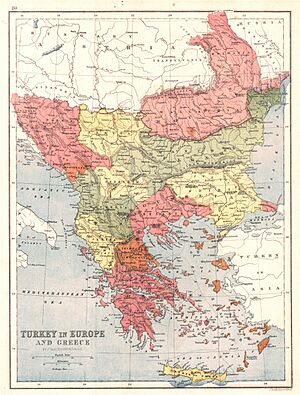

The Ottomans changed how Bulgarian lands were organized. They divided them into several large areas called vilayets. Each vilayet was led by a Sanjakbey or Subasi, who reported to a higher official called the Beylerbey. Much of the land was given to the Sultan's (the Ottoman ruler's) followers. These lands were like special gifts or fiefs (small timar, medium zeamet, and large hass).

These lands could not be sold or passed down to children. When the person holding the land died, it went back to the Sultan. Some lands were also private property of the Sultan or rich Ottoman families. Others were used to support religious groups, called vakιf. This system helped the army support itself and grow, allowing for more conquests and tighter control over new lands.

From the 1300s to the 1800s, Sofia was a very important city for the Ottoman Empire. It became the capital of Rumelia Eyalet, which was the main Ottoman province in Europe (the Balkans). Sofia was also the capital of the important Sanjak of Sofia. This area included all of Thrace with cities like Plovdiv and Edirne, and parts of Macedonia with Thessaloniki and Skopje.

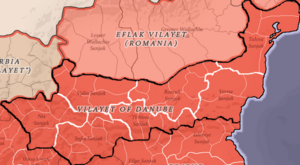

The Danube Vilayet was a major administrative area from 1864 to 1878, with its capital in Ruse. In the late 1800s, it covered a large area and included other regions like Vidin Eyalet, Silistra Eyalet, and Niš Eyalet.

Laws and Taxes for Bulgarians

Christians in Ottoman Bulgaria had to pay much higher taxes than Muslims. One important tax was the jizye, a poll tax paid instead of military service. This tax was a huge source of money for the Ottoman government. The region of Rumelia, which included Bulgaria, provided most of this tax money.

By the early 1600s, the timar land system mostly ended. Instead, land was given to important Ottoman officials as a way to collect taxes. This system often led to unfair treatment and harsh taxes for the people.

Bulgarians also paid other taxes, like a tithe (yushur), a land tax (ispench), and taxes on trade. They also had to do forced labor (avariz). In general, non-Muslims, called rayah, paid twice as much in taxes as Muslims.

Christians also faced other rules. They could not speak against Muslims in court. While they could practice their religion, they had to do so quietly. Loud prayers or ringing church bells were not allowed. They were also forbidden from certain jobs, riding horses, wearing certain colors, or carrying weapons.

However, some groups of Christians had special freedoms. For example, Dervendjis guarded important roads and passes. People in mining towns like Chiprovtsi also had fewer restrictions. Many important Bulgarian towns in the 1800s, like Gabrovo and Kalofer, grew because they once had this special dervendji status. Christians living on wakf lands also paid lower taxes and had more freedom.

Religion in Ottoman Bulgaria

The Ottoman Empire had a system called the millet system. This system allowed different religious groups to manage their own legal, religious, cultural, and family matters. However, this system did not fully help Bulgarians and other Orthodox Christians in the Balkans. The independent Bulgarian Patriarchate was destroyed, and all Bulgarian Orthodox churches came under the control of the Ecumenical Patriarch in Constantinople. They became part of the Rum millet (Greek Orthodox millet). This meant the system actually encouraged Bulgarians to become more like Greeks, rather than helping them keep their own culture.

Bulgarian stopped being a language used for writing books. The top church leaders were always Greek. Greek officials, called Phanariotes, tried to make Bulgarians more Greek starting in the early 1700s. This changed only after Bulgarians fought for their church's independence in the mid-1800s. The Bulgarian Exarchate, a separate Bulgarian Orthodox church, was finally created by the Sultan in 1870.

Non-Muslims usually did not serve in the Sultan's army. One sad exception was the "blood tax," known as devşirme. This was a system where young Christian Bulgarian boys were taken from their families. They were forced to become Muslims and then trained to be soldiers in the elite Janissary army or work in the Ottoman government. Boys were chosen from about one in forty families. They had to be unmarried and cut all ties with their families.

While some people have suggested that parents sometimes wanted their children to join the Janissaries for a good career, most experts disagree. Christian parents usually hated this forced recruitment. They would beg and try to pay to get their children out of it.

It was common for these boys to try and remember their old faith and homeland. For example, Stephan Gerlach wrote that they would talk about their homes and churches. They would agree that the Turkish religion was false. If someone had a book or could teach them about God, they would listen carefully.

When a Greek scholar visited Constantinople in 1491, he met many Janissaries who remembered their old religion and homeland. They even favored other Christians. One told him he regretted leaving his family's faith and secretly prayed to a cross at night.

History of Ottoman Bulgaria

Spread of Islam in Bulgaria

Islam spread in Bulgaria in two ways: through Muslims moving from Asia Minor and through native Bulgarians converting. The Ottomans moved large groups of people starting in the late 1300s and continuing into the 1500s. Most of these moves were forced. The first Muslim group to settle in present-day Bulgaria were Tatars who came willingly to farm. Another group were nomads who had problems with the Ottoman government. Both groups settled near Plovdiv. In 1418, another large group of Tatars was moved to Thrace. In the 1490s, over 1000 Turkoman families were moved to Northeastern Bulgaria.

At the same time, there are records of Bulgarians being forced to move to Anatolia. One group was moved after the fall of Veliko Tarnovo. Another was moved to İzmir in the mid-1400s. The goal of this "mixing of peoples" was to stop unrest in the conquered Balkan states. It also helped remove troublemakers from Anatolia.

However, the Ottomans never forced Bulgarians to convert to Islam. This was a claim made by Communist Bulgarian historians in the past. Most experts now agree that converting to Islam was a choice. It offered Bulgarians religious and economic benefits. According to Thomas Walker Arnold, Islam was not spread by force in Ottoman lands. A writer from the 1600s said that the Turks won converts more by cleverness than by force. They slowly removed Christianity from people's hearts.

So, in many cases, converting to Islam happened because of tax reasons. Muslims paid much lower taxes. While some say social status was more important, historian Halil İnalcık said that wanting to stop paying the jizya tax was a main reason for converting in the Balkans. Bulgarian researcher Anton Minkov also agreed it was one of several reasons.

Two big studies on why people converted to Islam in Bulgaria found many reasons. These studies looked at the Chepino Valley and the Gotse Delchev region. Reasons included:

- Many people already lived in these mountain areas.

- Christian Bulgarians moved from lowlands to avoid taxes in the 1400s.

- The regions were poor.

- Local Christians met nomadic Yörüks early on and learned about Islam.

- The Ottomans were often at war with the Habsburgs from the mid-1500s to the early 1700s.

- These wars led to huge expenses. The jizya tax increased six times from 1574 to 1691. A war tax (avariz) was also added.

- The Little Ice Age in the 1600s caused bad harvests and widespread hunger.

- Local landholders were very corrupt and overtaxed people.

All these factors led to a slow but steady increase in conversions to Islam. By the mid-1600s, the tax burden became so heavy that most remaining Christians either converted in large groups or moved to lowland areas.

Because of these problems, the population of Ottoman Bulgaria is thought to have dropped by half. It went from about 1.8 million people in the 1580s (1.2 million Christians and 0.6 million Muslims) to about 0.9 million in the 1680s (450,000 Christians and 450,000 Muslims). Before this, the population had grown steadily from about 600,000 in the 1450s.

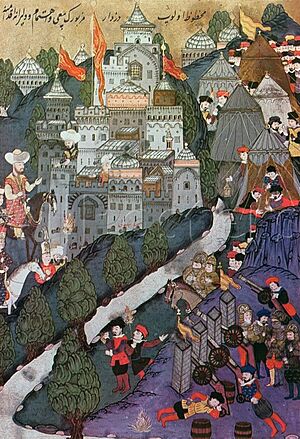

Early Rebellions and European Powers

Even though the Ottomans were powerful, there was resistance to their rule. The first revolt began around 1408. Two Bulgarian nobles, Konstantin and Fruzhin, rebelled and freed some areas for several years. The earliest sign of ongoing local resistance is from before 1450. Radik was recognized by the Ottomans as a leader in the Sofia region in 1413. But he later turned against them and is seen as the first hayduk (a type of rebel) in Bulgarian history. More than a century later, two Tarnovo uprisings happened in 1598 (First Tarnovo Uprising) and 1686 (Second Tarnovo Uprising) around the old capital of Tarnovo.

These were followed by the Catholic Chiprovtsi Uprising in 1688 and a rebellion in Macedonia led by Karposh in 1689. Both were encouraged by the Austrians during their long war with the Ottomans. All these uprisings failed and were put down very brutally. Most of them led to huge numbers of people being forced to leave their homes.

In 1739, the Treaty of Belgrade between the Austrian and Ottoman Empires ended Austria's interest in the Balkans for a century. But by the 1700s, the growing power of Russia began to be felt. The Russians, being fellow Orthodox Slavs, could connect with Bulgarians in a way the Austrians could not. The Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca in 1774 gave Russia the right to get involved in Ottoman affairs to protect the Sultan's Christian subjects.

Bulgarian National Awakening

The Bulgarian National Revival was a time of social and economic growth and a rise in national identity among Bulgarians under Ottoman rule. It is generally believed to have started in 1762 with the history book Istoriya Slavyanobolgarskaya, written by Paisius, a Bulgarian monk. This book led to the modern Bulgarian nationalism. The Revival lasted until Bulgaria's freedom in 1878, which came after the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-78.

The Millet system was a way for religious groups in the Ottoman Empire to have their own legal courts for personal matters. The Sultan saw the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople as the leader of all Orthodox Christians in his empire. After the Ottoman Tanzimat reforms (1839–76), Nationalism grew in the Empire. The term "millet" then referred to legally protected religious minority groups, similar to how other countries use the word nation. New millets were created in 1860 and 1870.

The Bulgarian Exarchate (a church that was almost fully independent) was created as a separate Bulgarian church based on ethnic identity. It was officially announced on May 23, 1872, in the Bulgarian church in Constantinople. This was done following a decree (firman) from Sultan Abdülaziz in 1870.

The creation of the Exarchate was a direct result of Bulgarian Orthodox people fighting against the control of the Greek Patriarchate of Constantinople in the 1850s and 1860s. In 1872, the Patriarchate accused the Exarchate of bringing ethno-national ideas into the Orthodox Church. The separation from the Patriarchate was officially called a schism (a split) by a council in Constantinople in September 1872. Despite this, Bulgarian religious leaders continued to expand the Exarchate's borders in the Ottoman Empire by holding votes in areas claimed by both churches.

In this way, the fight for a separate church helped create the modern Bulgarian nation, known as the Bulgar Millet.

Armed resistance against Ottoman rule grew in the late 1800s. It reached its peak with the April Uprising of 1876, which affected parts of the empire where Bulgarians lived. This uprising, along with Russia's interests in the Balkans, led to the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-1878. The war ended with Bulgaria becoming an independent state in 1878. However, under the Treaty of Berlin (1878), Bulgarians were divided, and the Principality of Bulgaria was much smaller than what Bulgarians had hoped for and what was first suggested in the Treaty of San Stefano.

Population Changes

From the 1300s to the early 1800s

The exact impact of the Ottoman conquest on Bulgaria's population is not fully known. However, the population of present-day Bulgaria in the 1450s is thought to have reached a low of 600,000 people. This included about 450,000 Christians and 150,000 Muslims (a 3:1 ratio of Christians to Muslims). This happened after many Muslims moved from Anatolia and many Christians moved to Wallachia. Both Christian and Muslim populations then grew steadily until the 1580s, reaching about 1.8 million. This included 1.2 million Christians and 0.6 million Muslims (a 2:1 ratio). The higher growth among Muslims was due to both conversions and new Muslim migrants from Anatolia.

From the mid-1500s to the late 1600s, the Ottoman Empire was almost constantly at war. This led to a greater need for taxes. The jizye tax rates increased six times, making Christians very poor. The Little Ice Age in the 1600s caused crop failures and widespread hunger. Several important Bulgarian uprisings, like the First Tarnovo Uprising and Chiprovtsi uprising, also led to many Christian Bulgarians fleeing to Wallachia and the Austrian Empire. Because of all this, the population of present-day Bulgaria in the 1680s is believed to have dropped to about 0.9 million. This was split evenly, with 450,000 Christians and 450,000 Muslims (a 1:1 ratio). From the early 1700s, the Christian population is thought to have started growing again.

1831 Ottoman Census

According to the 1831 Ottoman census, there were 496,744 taxable men in the areas that are now part of Bulgaria. This included 296,769 Christians, 181,455 Muslims, 17,474 Romani, 702 Jews, and 344 Armenians. This census only counted healthy men aged 15 to 60 who were not disabled.

Millets in present-day Bulgaria as per 1831 Ottoman Census Rayah (59.79%) Islam millet (36.5%) Gypsies (3.5%) Jews (0.1%) Armenians (0.1%)

| Millet | Republic of Bulgaria borders | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy taxable men aged 15–60 years | % | |||||||||

| Islam millet/Muslims | 181,455 | 36.5% | ||||||||

| Rayah/Orthodox Christians1 | 296,769 | 59.7% | ||||||||

| Gypsies/Romani | 17,474 | 3.5% | ||||||||

| Jews | 702 | 0.1% | ||||||||

| Armenians | 344 | 0.1% | ||||||||

| TOTAL | 496,744 | 100.0% | ||||||||

|

1No data about the Christian population of the kazas of Selvi (Sevlievo), Izladi (Zlatitsa), Etripolu (Etropole), Lofça (Lovech), Plevne (Pleven), Rahova (Oryahovo) as well as Tirnova (Veliko Tarnovo) and its three constitunet nahiyas.

2For figures comparable with post-1878 data, Arkadiev has suggested using the formula N=2 x (Y x 2.02), cf below, which would give a total population of 2,006,845, of whom 1,198,946 Orthodox Christians, 733,078 Muslims, 70,595 Romani, 2,836 Jews and 1,390 Armenians. |

||||||||||

Using a special calculation, the total population of present-day Bulgaria in 1831 would be around 2,006,845 people. This would include about 1,198,946 Orthodox Christians and 733,078 Muslims.

Ottoman Population Records (1860-1875) for the Future Principality of Bulgaria

The Principality of Bulgaria was created on July 13, 1878. It included five regions (sanjaks) that were part of the Ottoman Danube Vilayet. These were the Sanjaks of Vidin, Tirnova, Rusçuk, Sofya, and Varna. Other parts of the Danube Vilayet went to Serbia and Romania.

Ethnoconfessional Groups in the "Five Bulgarian Sanjaks" as per 1865 Pop. Registry Bulgarians (58.94%) Muslims (38.39%) Vlachs (0.99%) Jews (0.47%) Christian Roma (0.47%) Greeks (0.36%) Muslim Roma (0.21%) Armenians (0.17%)

According to Ottoman records from 1865, the male population of these five sanjaks was divided into these groups:

| Community | Rusçuk Sanjak | Vidin Sanjak | Varna Sanjak | Tırnova Sanjak | Sofya Sanjak | Principality of Bulgaria2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Islam Millet | 138,017 (61%) | 14,835 (13%) | 38,230 (74%) | 77,539 (40%) | 20,612 (12%) | 289,233 (38%) | ||||

| Muslim Roma | 312 (0%) | 245 (0%) | 118 (0%) | 128 (0%) | 766 (0%) | 1,569 (0%) | ||||

| Bulgar Millet | 85,268 (38%) | 93,613 (80%) | 9,553 (18%) | 113,213 (59%) | 142,410 (86%) | 444,057 (59%) | ||||

| Ullah Millet | 0 (0%) | 7,446 (6%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 7,446 (1%) | ||||

| Ermeni Millet | 926 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 368 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1,294 (0%) | ||||

| Rum Millet | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2,693 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2,693 (0%) | ||||

| Non-Muslim Romani people | 145 (0%) | 130 (0%) | 999 (2%) | 1,455 (1%) | 786 (0%) | 3,515 (0%) | ||||

| Yahudi Millet | 1,101 (0%) | 630 (1%) | 14 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1,790 (1%) | 3,535 (0%) | ||||

| TOTAL | 225,769 (100%) | 116,899 (100%) | 51,975 (100%) | 192,335 (100%) | 166,364 (100%) | 753,342 (100%) | ||||

|

1 Male/female-aggregated estimates for the total population and all ethnoconfessional communities can be calculated using the formula suggested by Ubicini and Michael Palairet (N x 2), which would give a total population for 1865 of 1,506,684 people, divided into 888,114 Bulgarians, 578,466 Muslims, 14,892 Vlachs, etc.

2 Refers to the Sanjaks of Vidin, Tirnova, Rusçuk, Sofya and Varna, which were united into the Principality of Bulgaria by the decisions of the Congress of Berlin in 1878. |

||||||||||

Between 1855 and 1865, the population of the Danube Vilayet changed a lot. The Ottoman government settled over 300,000 Crimean Tatars and Circassians in the area. This happened in two waves. The first wave, from 1855 to 1862, brought 142,852 Tatars and Nogais, plus some Circassians. The second wave in 1864 brought about 35,000 Circassian families (140,000–175,000 people).

According to Turkish scholar Kemal Karpat, these new settlers helped increase the Muslim population. They made up for earlier losses and even led to overall growth. Karpat also noted that non-Muslims grew faster (2% per year) than Muslims (0%).

Another scholar, Koyuncu, also saw faster growth among non-Muslims. He said that the huge increase in the Muslim population (84.23%) in the five Bulgarian sanjaks from 1860 to 1875 was due to the settlement of Crimean Tatars and Circassians. Non-Muslims grew by 53.29% in the same period.

Ethnoconfessional Groups in the "Five Bulgarian sanjaks" as per 1873-74 Census Bulgarians (57.60%) Establ. Muslims (34.17%) Çerkes Muhacir (2.68%) Muslim Roma (2.39%) Misc. Christians (1.47%) Christian Roma (0.70%) Jews (0.44%) Greeks (0.38%) Armenians (0.17%)

Here are the male population figures for the same five sanjaks in 1873-74:

| Community | Rusçuk Sanjak | Vidin Sanjak | Varna Sanjak | Tırnova Sanjak | Sofya Sanjak | Principality of Bulgaria2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Islam Millet | 164,455 (53%) | 20,492 (11%) | 52,742 (61%) | 88,445 (36%) | 27,001 (13%) | 353,135 (34%) | ||||

| Circassian Muhacir | 16,588 (5%) | 6,522 (4%) | 4,307 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 202 (0%) | 27,589 (3%) | ||||

| Muslim Roma | 9,579 (3%) | 2,783 (2%) | 2,825 (3%) | 6,545 (3%) | 2,964 (1%) | 24,696 (2%) | ||||

| Bulgar Millet | 114,792 (37%) | 131,279 (73%) | 21,261 (25%) | 148,713 (60%) | 179,202 (84%) | 595,247 (58%) | ||||

| Vlachs, Catholics, etc. | 500 (0%) | 14,690 (8%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 15,190 (1%) | ||||

| Rum Millet (Greeks) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 3,421 (4%) | 494 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 3,915 (0%) | ||||

| Non-Muslim Roma | 1,790 (1%) | 2,048 (1%) | 331 (0%) | 1,697 (1%) | 1,437 (1%) | 7,303 (1%) | ||||

| Yahudi Millet | 1,102 (0%) | 1,009 (1%) | 110 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2,374 (1%) | 4,595 (0%) | ||||

| TOTAL | 309,797 (100%) | 178,823 (100%) | 85,805 (100%) | 245,894 (100%) | 213,180 (100%) | 1,033,499 (100%) | ||||

|

1 Male/female-aggregated estimates for the total population and all ethnoconfessional communities can be calculated using the formula suggested by Ubicini and Michael Palairet (N x 2), which would give a total population for 1875 of 2,066,998, divided into 1,190,494 Bulgarians, 706,270 Established Muslims, 55,178 Circassian Muhacir, 49,392 Muslim Romani, 30,380 Miscellaneous Christians, 14,606 Christian Romani, 9,190 Jews, 7,830 Greeks and 3,598 Armenians.

2 Refers to the Sanjaks of Vidin, Tirnova, Rusçuk, Sofya and Varna, which were united into the Principality of Bulgaria by the decisions of the Congress of Berlin in 1878. |

||||||||||

The Congress of Berlin changed some borders. The kaza of Cuma-i Bâlâ (with 2,896 Muslim males and 8,038 non-Muslim males) went back to the Ottoman Empire. The kaza of Mankalya (with 6,675 Muslim males and 499 non-Muslim males) went to Romania. The kaza of Iznebol (with 149 Muslim males and 7,072 non-Muslim males) joined the Principality of Bulgaria.

Ethnoconfessional Groups in the Future Principality of Bulgaria in 1875 Bulgarians (56.96%) Turks (26.22%) Muslim Muhacir (10.35%) Muslim Roma (2.35%) Misc. Christians (1.46%) Pomaks (0.96%) Christian Roma (0.70%) Jews (0.44%) Greeks (0.38%) Armenians (0.17%)

In 1874, a quick summary of the Danube Vilayet Census showed more Circassian Muhacir (refugees/settlers) than the final results. It also showed slightly fewer "established Muslims." The difference between "Established" and "Muhacir" Muslims in the census was not about where they came from. Instead, it was about whether they had to pay taxes. Settlers who had been there longer and whose tax breaks had ended were counted as "Established." Newer settlers who still had tax breaks were counted as "Muhacir."

The settlement of Crimean Tatars and Nogais from 1855-1862 was well documented. About 93,000 of these settlers were given land in areas that became part of the Principality of Bulgaria.

After adjusting for border changes and how different groups were counted, the population of the future Principality of Bulgaria in 1875 was estimated at 2,085,224 people. This included:

- 1,187,564 Bulgarians (56.96%)

- 546,776 Turks (26.22%)

- 215,828 Crimean and Circassian Muhacir (10.35%)

- 49,392 Muslim Romani (2.35%)

- 30,380 other Christians (1.46%)

- 20,000 Pomaks (0.96%)

- 14,606 Christian Romani (0.70%)

- 9,190 Jews (0.44%)

- 7,830 Greeks (0.38%)

- 3,598 Armenians (0.17%)

It's important to note that 10% of the total population, and 25% of all Muslims, were non-native refugees or settlers. They had arrived only 10 to 20 years before. The Ottoman authorities carefully chose where to settle them. This was done to increase the Muslim population in the Balkans, create a barrier against Russia, and balance the Christian population in Rumelia.

Nusret Pasha, who led the Silistra Eylaet Colonisation Commission, stated in 1868 that Circassians were settled along the Danube to act as a "live fortification and barrier against Russia."

Ottoman Population Records (1876) for Future Eastern Rumelia

The other Bulgarian territory created from the Ottoman Empire was the self-governing province of Eastern Rumelia. It included the Sanjak of İslimye, most of the Sanjak of Filibe, and smaller parts of the Sanjak of Edirne.

Here are the district-by-district male population records from the 1876 Ottoman records, based on the 1875 Adrianople Vilayet census. The total figures at the bottom are estimates for both males and females:

Ethnoconfessional Groups in the Future Eastern Rumelia in 1876 Bulgarians (57.96%) Turks (28.21%) Greeks (3.91%) Muslim Roma (3.47%) Pomaks (2.74%) Muhacir (2.19%) Christian Roma (0.73%) Jews (0.64%) Armenians (0.17%)

| Kaza (District) | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Islam millet | % | Bulgar & Rum millet | % | Ermeni millet | % | Roman Catholic | % | Yahudi millet | % | Muslim Roma | % | Non-Muslim Roma | % | Total | % | |

| Filibe/Plovdiv | 35,400 | 28.1 | 80,165 | 63.6 | 380 | 0.3 | 3,462 | 2.7 | 691 | 0.5 | 5,174 | 4.1 | 495 | 0.4 | 125,767 | 100.00 |

| Pazarcık/Pazardzhik | 10,805 | 22.8 | 33,395 | 70.5 | 94 | 0.2 | - | 0.0 | 344 | 0.7 | 2,120 | 4.5 | 579 | 1.2 | 47,337 | 100.00 |

| Hasköy/Haskovo | 33,323 | 55.0 | 25,503 | 42.1 | 3 | 0.0 | - | 0.0 | 65 | 0.1 | 1,548 | 2.6 | 145 | 0.2 | 60,587 | 100.00 |

| Zağra-i Atik/Stara Zagora | 6,677 | 20.0 | 24,857 | 74.5 | - | 0.0 | - | 0.0 | 740 | 2.2 | 989 | 3.0 | 90 | 0.3 | 33,353 | 100.00 |

| Kızanlık/Kazanlak | 14,365 | 46.5 | 14,906 | 48.2 | - | 0.0 | - | 0.0 | 219 | 0.7 | 1,384 | 4.5 | 24 | 0.0 | 30,898 | 100.00 |

| Çırpan/Chirpan | 5,158 | 23.9 | 15,959 | 73.8 | - | 0.0 | - | 0.0 | - | 0.0 | 420 | 1.9 | 88 | 0.4 | 21,625 | 100.00 |

| - | - | - | ||||||||||||||

| - | - | 0.0 | - | 0.0 | 1.2 | - | 0.0 | |||||||||

| Filibe sanjak subtotal | 105,728 | 33.07 | 194,785 | 60.92 | 477 | 0.15 | 3,642 | 1.14 | 2,059 | 0.64 | 11,635 | 3.64 | 1,421 | 0.44 | 319,747 | 100.00 |

| İslimye/Sliven | 8,392 | 29.8 | 17,975 | 63.8 | 143 | 0.5 | - | 0.0 | 158 | 0.6 | 596 | 2.1 | 914 | 3.2 | 28,178 | 100.00 |

| Yanbolu/Yambol | 4,084 | 30.4 | 8,107 | 60.4 | - | 0.0 | - | 0.0 | 396 | 3.0 | 459 | 3.4 | 377 | 3.2 | 13,423 | 100.00 |

| Misivri/Nesebar | 2,182 | 40.0 | 3,118 | 51.6 | - | 0.0 | - | 0.0 | - | 0.0 | 153 | 2.8 | - | 0.0 | 5,453 | 100.00 |

| Karinâbâd/Karnobat | 7,656 | 60.5 | 3,938 | 31.1 | - | 0.0 | - | 0.0 | 250 | 2.0 | 684 | 5.4 | 125 | 1.0 | 12,653 | 100.00 |

| Aydos/Aytos | 10,858 | 76.0 | 2,735 | 19.2 | 19 | 0.1 | - | 0.0 | 36 | 0.2 | 584 | 4.1 | 46 | 0.3 | 14,278 | 100.00 |

| Zağra-i Cedid/Nova Zagora | 5,310 | 29.4 | 11,777 | 65.2 | - | 0.0 | - | 0.0 | - | 0.0 | 880 | 4.9 | 103 | 0.6 | 18,070 | 100.00 |

| Ahyolu/Pomorie | 1,772 | 33.7 | 3,113 | 59.2 | - | 0.0 | - | 0.0 | - | 0.0 | 378 | 7.2 | 2 | 0.0 | 5,265 | 100.00 |

| Burgas | 4,262 | 22.1 | 14,179 | 73.6 | 46 | 0.2 | - | 0.0 | 4 | 0.0 | 448 | 2.3 | 320 | 1.6 | 19,259 | 100.00 |

| İslimye sanjak subtotal | 44,516 | 38.2 | 64,942 | 55.7 | 208 | 0.2 | - | 0.0 | 844 | 0.6 | 4,182 | 3.6 | 1,887 | 1.6 | 116,579 | 100.00 |

| Male Population İslimye & Filibe sanjak |

150,244 | 34.43 | 259,727 | 59.53 | 685 | 0.16 | 3,642 | 0.83 | 2,903 | 0.67 | 15,817 | 3.63 | 3,308 | 0.76 | 436,362 | 100.00 |

| Total Population3 Islimiye & Filibe sanjak | 300,488 | 34.43 | 519,454 | 59.53 | 1,370 | 0.16 | 7,284 | 0.83 | 5,806 | 0.67 | 31,634 | 3.63 | 6,616 | 0.76 | 872,652 | 100.00 |

| Kızılağaç/Elhovo2 | 1,425 | 9.6 | 11,489 | 89.0 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 12,914 | 100.00 |

| Manastır/Topolovgrad2 | 409 | 1.5 | 26,139 | 98.5 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 26,548 | 100.00 |

| Eastern Rumelia GRAND TOTAL3 | 302,322 | 33.15 | 557,082 | 61.08 | 1,370 | 0.15 | 7,284 | 0.79 | 5,806 | 0.64 | 31,634 | 3.47 | 6,616 | 0.72 | 912,114 | 100.00 |

|

1Kaza to remain in the Ottoman Empire.

2Figures available for total population and for Islam millet and Bulgar millet/Rum millet only. 3 Male/female aggregated figures presuming equal number of men and women, as suggested by Ubicini and Palairet. |

||||||||||||||||

According to British diplomat Drummond-Wolff, the Islam millet also included 25,000 Muslim Bulgarians, 10,000 Tatars and Nogays, and 10,000 Circassians. British historian R.J. Moore found 4,000 Greek males (or 8,000 total) in the Sanjak of Filibe. The British consular service found an additional 22,000 Greeks in the Sanjak of İslimye and 5,693 in the Manastır nahiya. This means a total of 35,693 Greeks were counted with the Orthodox Bulgarians. All Catholics were Bulgarian Paulicians.

So, before the Russo-Turkish War (1877-1878), Eastern Rumelia's total population of 912,114 people was made up of:

- 528,673 Christian Bulgarians (57.96%)

- 257,322 Turks (28.21%)

- 35,693 Greeks (3.91%)

- 31,634 Muslim Romani (3.47%)

- 25,000 Pomaks (2.74%)

- 20,000 Muhacir (2.19%)

- 6,616 Christian Romani (0.73%)

- 5,806 Jews (0.64%)

- 1,370 Armenians (0.15%)

See also

- Ottoman Vardar Macedonia

- Bulgarian Exarchate

- April Uprising of 1876

- Constantinople Conference

- Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878

- Treaty of San Stefano

- Treaty of Berlin (1878)

- Kresna–Razlog uprising

- Ilinden–Preobrazhenie Uprising