History of Thessaly facts for kids

Thessaly is a region in central Greece with a long and exciting past. Its story stretches from ancient times all the way to today. This article will explore the many changes and events that shaped Thessaly.

Contents

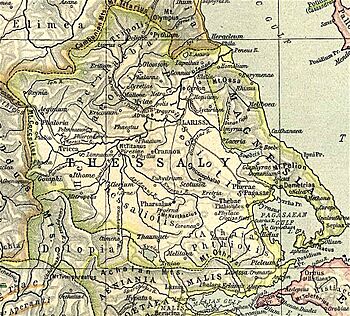

The Land of Thessaly

Thessaly is famous for its large, flat Thessalian plain. This plain was formed by the Pineios River. Mountains surround the plain, especially the Pindus range to the west. These mountains separate Thessaly from another region called Epirus. Only two mountain paths, the Porta pass and the Metsovo pass (in summer), connect these two areas. To the south, the narrow coastal path of Thermopylae links Thessaly with southern Greece. In the north, Thessaly shares a border with Macedonia.

Ancient Times in Thessaly

People first lived in Thessaly during the late Stone Age. But during the early New Stone Age, many more people moved here. Over 400 ancient sites have been found from this time, some of them fortified. One important site is Sesklo. Later, during the Mycenaean period, the main city was Iolcos. This city is famous in legends, like the story of Jason and the Argonauts.

The Archaic Period (9th-6th Century BC)

- Further information: Archaic Greece

A special Thessalian identity and culture began to form around the 9th century BC. It was a mix of local people and new arrivals from Epirus. Their main center was Pherae. From there, they quickly spread across the Pineios plain and towards the Malian Gulf. The Thessalians spoke a unique form of Greek.

By the late 7th century BC, the Thessalians took control of the surrounding areas. They captured Anthela and gained power over a local religious group called an amphictyony. This also gave them a big role in the important Delphic Amphictyony. They provided many leaders and oversaw the Pythian Games. After a war (595–585 BC), the Thessalians briefly controlled Phocis. However, another group, the Boeotians, pushed them back.

In the 7th century BC, Thessaly became home to powerful noble families. These families owned huge amounts of land. They used serfs, called penestae, to work the land. This was a unique feature of Thessaly. The most important families were the Aleuadae of Larissa, the Echecratidae of Pharsalus, and the Scopadae of Crannon. Their leaders were often called "kings." A leader named Aleuas Pyrrhos made the nobles even stronger. He reorganized the Thessalian League, dividing it into four parts. Each part had to provide 40 horsemen and 80 foot soldiers.

The Classical Period (5th-4th Century BC)

- Further information: Classical Greece

In the summer of 480 BC, the Persians invaded Thessaly. The Greek army guarding the Vale of Tempe left before the Persians arrived. Soon after, Thessaly surrendered. The Thessalian family of Aleuadae even joined the Persians.

During the Peloponnesian War, Thessaly usually supported Athens. They often stopped Spartan troops from crossing their land. In the 4th century BC, Thessaly became dependent on Macedon. Later, in the 2nd century BC, Thessaly, like the rest of Greece, came under the control of the Roman Republic.

Roman Rule in Thessaly

From 27 BC, Thessaly was part of the Roman province of Achaea. Its capital was Corinth. Later, under Emperor Antoninus Pius (r. 138 – 161), Thessaly was separated from Achaea. It became part of the province of Macedonia. Eventually, it became its own separate province.

When the Roman Empire split in 395 AD, Thessaly remained part of the East Roman (Byzantine) Empire. Greece was far from the empire's borders and didn't have many defenses. This led to a lot of damage from barbarian raids. In 395–397, Visigoths led by Alaric occupied Thessaly. They were later driven out. The Vandals raided the coasts in 466–475. In 473, the Ostrogoths captured Larissa. They left for Italy in 488.

Under Emperor Justinian I (r. 527 – 565), there were serious efforts to build fortifications. A permanent army was stationed at Thermopylae. Despite these raids, the Roman government in Thessaly continued to work. Public life also seemed to go on for much of the 6th century. However, the raids, two big earthquakes, and the Plague of Justinian caused the population to drop.

The Middle Ages

Slavic Invasions and Byzantine Return

The old Roman order in Greece was broken by Slavic invasions after 578. The first big raid was in 581. The Slavs stayed in Greece until 584. The Byzantine Empire was busy fighting wars in the east and north. So, they couldn't stop these raids. After 602, the Danube border collapsed, leaving the Balkans open to Slavic settlement.

Slavic settlement affected the Peloponnese and Macedonia more than Thessaly. Fortified towns mostly stayed in Greek hands. However, in the early 7th century, Slavs raided Thessaly freely. Some cities in Thessaly disappeared from records during the 7th century. Slavs settled in the northern and northeastern parts of the region.

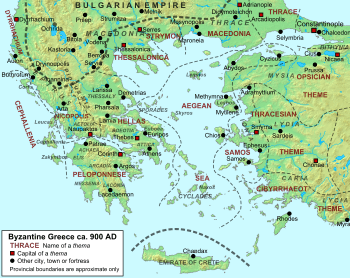

Emperor Constans II (r. 641 – 668) tried to bring back imperial rule in 658. This led to some peace with the Slavic tribes in southern Greece. The parts of Thessaly that remained under Byzantine control were along the Aegean coast. These areas became part of the "Theme of Hellas." This was a military district created between 687 and 695.

Thessaly, like much of northern Greece, suffered from raids by the Bulgarians starting in 773. At the same time, more Slavs moved into Greece around 746/7. In 783, a Byzantine general led a large campaign across Greece. He brought the local Slavs back under imperial control. Despite continued raids by Bulgarians and Arab pirates, Thessaly slowly recovered. There were signs of new wealth and trade. At least nine new cities appeared in Thessaly, and older ones were resettled.

Byzantine Rule (10th–12th Centuries)

- Further information: Great Vlachia

During the 10th century, the threat from Arab pirates ended. But the threat from Bulgaria remained. In 986, the Bulgarian tsar Samuel captured Larissa and occupied Thessaly. He led another large attack in 997 but was badly defeated. In the early 11th century, Thessaly became part of the "Theme of Thessalonica." The region then had a long period of peace. It was only interrupted by raids in 1040–1041, plundering in 1064, and a brief Norman attack in 1082–1083.

The Vlachs, a group of people who spoke a Romance language, are first mentioned in Thessaly in the 11th century. In the 12th century, a traveler noted a district called "Vlachia" near Halmyros. Another historian placed a "Great Vlachia" near Meteora. This area was later known as "Vlachia in Hellas."

After a Norman invasion failed, Emperor Alexios I gave trading rights to the Republic of Venice. This allowed them to set up trade colonies in towns like Demetrias. These deals marked the beginning of Italian traders taking over Byzantine trade. Later, in 1198, Emperor Alexios III Angelos (r. 1195 – 1203) had to give Venice even more rights.

By the end of the 12th century, Thessaly was divided into smaller areas. These divisions are mentioned in documents from 1198 and 1204. They show areas owned by the imperial family and Slavic settlements.

Latin and Epirote Rule (13th Century)

After Constantinople was sacked in 1204 by the Fourth Crusade, a Greek ruler named Leo Sgouros marched into central Greece. At Larissa, he met the deposed Emperor Alexios III. But soon, Crusaders led by Boniface of Montferrat arrived. Boniface wanted to expand his new Kingdom of Thessalonica. Sgouros gave up Thessaly without a fight. Boniface divided the captured lands among his followers.

However, in 1212, Michael I Komnenos Doukas (r. 1205 – 1214/5), ruler of the independent Greek state of Epirus, invaded Thessaly. He defeated the local Lombard nobles. Larissa and much of central Thessaly came under Epirote rule. This separated Thessalonica from the Crusader states in southern Greece. Michael's half-brother, Theodore Komnenos Doukas (r. 1215 – 1230), finished the job. By 1222/3, he had recovered almost all of Thessaly. In December 1224, Theodore also conquered Thessalonica and declared himself emperor.

Thessaly remained connected to Thessalonica until 1239. After Theodore's death in 1241, Thessaly came under the control of the Epirote ruler, Michael II Komnenos Doukas (r. 1230 – 1268). After a battle in 1259, Thessaly was taken by the Empire of Nicaea. But an Epirote counter-attack in 1260 recovered most of the province.

Thessaly as an Independent State

When Michael II died in 1267/8, his lands were divided. His illegitimate son, John Doukas (r. 1267/8 – 1289), received Thessaly. John was married to a Thessalian Vlach princess. Thessaly and Epirus were politically separate but shared many similarities. Both were unwilling to accept the revived Byzantine Empire. Both formed alliances with Latin states in southern Greece to stay independent. Both were eventually reunited with the Byzantines in the 1330s.

From his capital at Neopatras, John I Doukas ruled Thessaly as an almost independent state. He recognized the Byzantine emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos (r. 1259 – 1282) as his overlord. In return, he received the title of sebastokrator. But John I Doukas remained against the Byzantines. He allied with Latin powers like Charles of Anjou and the Duchy of Athens. Michael VIII tried to unite the Orthodox and Catholic Churches. John used this as a reason to oppose him. He offered safety to those against the union.

Around 1273–75, Michael VIII sent a large army against John. The Byzantine army quickly moved through Thessaly. They trapped John and his men at Neopatras. John managed to escape and got help from Athens. With this help, he defeated the Byzantine army at the Battle of Neopatras. In return for this help, John gave his daughter Helena to the future Duke of Athens. He also gave her towns like Zetounion and Gardiki as a dowry. Another Byzantine attack in 1277 was also unsuccessful. Finally, in 1282, Michael VIII himself marched against John but died on the way.

After John's death, his wife had to accept the rule of Michael VIII's successor, Andronikos II Palaiologos (r. 1282 – 1328). This was to protect her young sons, Constantine and Theodore. In 1295, the brothers invaded Epirus. Both Constantine and Theodore died in 1303. Thessaly was left to Constantine's young son, John II Doukas. Since he was underage, the Duke of Athens, Guy II de la Roche (r. 1287 – 1308), became his guardian. John II continued his grandfather's pro-Latin policy. He had close ties with the Venetians, who bought farm goods from Thessaly.

In 1308, Guy II de la Roche died. John II Doukas used this chance to break free from Athens. He turned to Byzantium for support. In early 1309, the Catalan Company, a group of soldiers, crossed into Thessaly. Their arrival worried John II Doukas. The Catalans agreed to pass peacefully through Thessaly. They went south towards the Frankish states. The new Duke of Athens, Walter of Brienne, hired the Company to fight Thessaly. The Catalans captured many fortresses and plundered the rich plain. John Doukas was forced to make peace with Walter. But Walter tried to break his deal with the Catalans. This led to a fight. At the Battle of Halmyros on March 15, 1311, the Catalans crushed the Athenian army. After the battle, the Catalan Company occupied the defenseless duchy.

Thessaly in the 14th and 15th Centuries

The Catalans held parts of southern Thessaly for a while. They raided the region in the following years. John Doukas's power in Thessaly grew weaker. Large landowners became almost independent. They had their own contacts with the Byzantine court. Around 1315, John had to formally recognize the Byzantine Empire's rule. He married Irene Palaiologina, the daughter of Emperor Andronikos II Palaiologos.

When John Doukas died in 1318, the Catalans of Athens quickly captured southern Thessaly. Between 1318 and 1325, the Catalans took Neopatras and other towns. This area became the new, Catalan-controlled Duchy of Neopatras. Venice also took advantage of the chaos to gain the port of Pteleos.

The central and northern parts of Thessaly remained in Greek hands. But without a central ruler, the area split among competing leaders. The north came under Byzantine control from Thessalonica. In the center, three powerful nobles emerged. Stephen Gabrielopoulos of Trikala was the most successful. He gained recognition from the Byzantine court. He was given the title of sebastokrator. Around this time, larger groups of Albanians began to settle in Thessaly.

When Gabrielopoulos died around 1333, the Epirote ruler John II Orsini (r. 1323 – 1335) tried to seize his lands. But the Byzantines under Andronikos III Palaiologos (r. 1328 – 1341) moved in. They took direct control over the northern and western parts of the region.

The successful Byzantine reconquest was led by John Kantakouzenos. When the Byzantine civil war of 1341–47 broke out, Thessaly and Epirus quickly sided with him. Kantakouzenos' cousin, John Angelos, ruled the two regions until his death in 1348. Then, they fell to the growing Serbian Empire of Stefan Dushan. Dushan appointed his general Gregory Preljub as governor of Thessaly. Preljub ruled until his death in 1355 or 1356. In 1350, Kantakouzenos, now emperor, tried to reconquer Thessaly. But he failed to capture Servia.

Preljub's death and Dushan's death left a power vacuum in Thessaly. Nikephoros Orsini, an exiled son of John II Orsini, tried to claim the region. He sailed to Thessaly and quickly captured it. He then conquered Aetolia and Acarnania. Nikephoros fought with the Albanians and was killed in 1359. After Nikephoros' death, Thessaly was taken over by Dushan's half-brother Simeon Uroš. Simeon Uroš ruled from Trikala until his death in 1370. He was known for supporting the Meteora monasteries. His son John Uroš succeeded him until 1373. Then, Thessaly was ruled by Alexios Angelos Philanthropenos and later Manuel Angelos Philanthropenos. They recognized Byzantine rule until around 1393. At that time, the region was conquered by the Ottoman Empire.

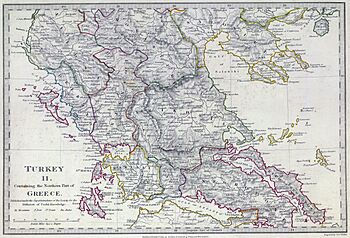

Ottoman Period

- Further information: Sanjak of Tirhala

The Ottomans first invaded Thessaly in 1386. They captured Larissa for a time. Around 1393, the second phase of the invasion began. The Ottomans defeated Manuel Angelos Philanthropenos and recaptured Larissa. The conquest of Thessaly was finished by 1394 under Sultan Bayezid I. Fortresses like Volos and Neopatras were taken. In 1395/6, Trikala also fell.

After a big battle in 1402, the Ottomans were weakened. They were forced to return the eastern coasts of Thessaly to Byzantine rule. By 1444, the entire region was finally conquered by the Turks. Only Pteleos remained in Venetian hands until 1470.

The newly conquered region was first ruled by powerful Ottoman lords. These lords brought settlers from Anatolia to repopulate the area. Soon, Muslim settlers or converts controlled the lowlands. Christians lived in the mountains around the Thessalian plain. The area was generally peaceful. But banditry was common. This led to the creation of the first state-approved Christian self-governing groups called armatoliks. The most famous was in Agrafa. Greek uprisings happened in 1600/1 and 1612. More revolts occurred during the Morean War (1684–1699) and the Orlov Revolt (1770).

After 1780, Ali Pasha of Ioannina took control of Thessaly. He made his rule stronger after 1808. However, his heavy taxes ruined the province's trade. This, along with a plague in 1813, reduced the population to about 200,000 by 1820. When the Greek War of Independence began in 1821, Greek uprisings happened in the Pelion and Olympus mountains. But Ottoman armies quickly put them down. Thessaly remained under Ottoman rule until 1881. It was then given to Greece under the terms of the Convention of Constantinople.

Modern Era

After joining Greece, Thessaly was divided into four prefectures: Larissa, Magnesia, Karditsa, and Trikala. In 1897, the Ottomans overran the region during a brief war. The Ottoman army left after the war. But small changes were made to the border in the Ottomans' favor.

The early years of Greek rule in Thessaly were dominated by farming issues. The area kept its large Ottoman-era landholdings. Landlords had great power. They treated their tenant farmers almost like serfs. Tensions led to the Kileler uprising in March 1910. The problem was finally solved through a large land redistribution program. This was done by the governments of Eleftherios Venizelos.

During World War I, Thessaly was a neutral zone. It was between the pro-Entente government in Thessaloniki and the royal, pro-Central Powers government in Athens. During World War II, the Italian army occupied the area from 1941–43. The Germans occupied it from 1943–44. Thessaly became a major center of the Greek Resistance. The Italian Pinerolo Division famously joined the guerrillas in 1943.

Sources

- Fine, John V. A. Jr. (1991). [History of Thessaly at Google Books The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century]. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08149-7. History of Thessaly at Google Books.

- Fine, John Van Antwerp (1994). [History of Thessaly at Google Books The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest]. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08260-4. History of Thessaly at Google Books.

- Geanakoplos, Deno John (1959). [History of Thessaly at Google Books Emperor Michael Palaeologus and the West, 1258–1282: A Study in Byzantine-Latin Relations]. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. OCLC 1011763434. History of Thessaly at Google Books.

- "The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium".. (1991). Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

- Koder, Johannes; Hild, Friedrich (1976) (in German). Tabula Imperii Byzantini, Band 1: Hellas und Thessalia. Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. ISBN 978-3-7001-0182-6.

- Miller, William (1908). The Latins in the Levant: A History of Frankish Greece (1204–1566). London: John Murray. OCLC 563022439. https://archive.org/details/latinsinlevanthi00mill/.

- Naval Intelligence Division (1944). Greece: Physical Geography, History, Administration and Peoples. Geographical handbook Series BR 516. London: Naval Intelligence Division. https://archive.org/details/greece0001grea.

- Nicol, Donald M. (1993). [History of Thessaly at Google Books The Last Centuries of Byzantium, 1261–1453] (Second ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-43991-6. History of Thessaly at Google Books.

- Savvides, Alexis G. C. (2000). "Tesalya". The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume X: T–U. Leiden: E. J. Brill. 420–422.

- Treadgold, Warren (1997). [History of Thessaly at Google Books A History of the Byzantine State and Society]. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-2630-2. History of Thessaly at Google Books.

- Van Tricht, Filip (2011). [History of Thessaly at Google Books The Latin Renovatio of Byzantium: The Empire of Constantinople (1204–1228)]. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-20323-5. History of Thessaly at Google Books.

- Yerolimpos, Alexandra (2000). "Tirḥāla". The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume X: T–U. Leiden: E. J. Brill. 539–540.

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |