History of nursing facts for kids

The word "nurse" first came from the Latin word "nutrire," which meant "to suckle" or "to nourish." This referred to a wet-nurse, someone who breastfed another's baby. It wasn't until the late 1500s that the word "nurse" started to mean a person who cares for sick or injured people.

For a very long time, many cultures had people who dedicated their lives to caring for others, often for religious reasons. Both Christian and Muslim communities had dedicated nurses from their earliest days. In Europe, before modern nursing began, Catholic nuns and military groups often provided care similar to nursing. It took until the 1800s for nursing to become a job that anyone could do, not just those in religious orders.

Contents

Early Care and Healing

The very first history of nurses is hard to trace because there aren't many written records. But caring for the sick has always been a natural extension of women's roles, much like a wet-nurse caring for a baby.

Ancient Hospitals and Healers

Around 268 BC to 232 BC, the Buddhist Indian ruler Ashoka the Great ordered hospitals to be built along travel routes. These hospitals were meant to have good tools, medicines, and skilled doctors. If there were no medicines, the state would provide them. This system of public hospitals continued in India for many centuries.

About 100 BC, an important Indian text called the Charaka Samhita was written. It said that good medical care needs four things: a patient, a doctor, a nurse, and medicines. It described a good nurse as someone who is knowledgeable, skilled at preparing medicines, kind to everyone, and clean.

The first known Christian nurse, Phoebe, is mentioned in the Bible around AD 50. St. Paul sent Phoebe to Rome as the first visiting nurse.

From its very beginning, Christianity encouraged its followers to care for the sick. Early Christians were known for nursing the sick and dying, even during major epidemics. This kindness helped them gain many friends and supporters.

After AD 325, Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire. This led to more places being built to care for the sick. Some of the earliest hospitals were built by St. Basil the Great around AD 370 in modern-day Turkey. Saint Fabiola built one in Rome around AD 390, and Saint Sampson built one in Constantinople. St. Basil's hospital was like a small city, with separate buildings for different types of patients, including a section for people with leprosy. Eventually, hospitals were built in every major church town.

Christian ideas about helping others led to the growth of organized nursing and hospitals. Leaders like St. Benedict of Nursia (480-547) saw medicine as a way to offer hospitality. Later, Catholic groups like the Dominicans and Carmelites lived in religious communities and worked to care for the sick.

Some hospitals had libraries and training programs. Doctors wrote down their medical studies. So, in-patient medical care, like what we call a hospital today, was an idea that grew from Christian kindness and new ideas from the Byzantine Empire. Byzantine hospitals had chief doctors, professional nurses, and assistants. By the 1100s, Constantinople had two well-organized hospitals with male and female doctors. They had special wards for different diseases.

In the early 600s, Rufaidah bint Sa’ad became the first known Muslim nurse. She learned medical skills from her father. After she led a group of women to treat injured fighters, Muhammad allowed her to set up a tent near a mosque to care for the sick and needy.

Medieval European Care

Hospitals in Medieval Europe were similar to those in the Byzantine Empire. They were often religious communities, and monks and nuns provided the care. An old French name for a hospital was hôtel-Dieu, meaning "hostel of God." Some hospitals were part of monasteries, while others were independent. They often had their own land to provide income. Not all medieval hospitals cared for the sick; some were for the poor or for pilgrims.

The first Spanish hospital, founded by the Catholic bishop Masona in AD 580, was an inn for travelers and a hospital for local people. It had farms to feed its patients and guests. This hospital had doctors and nurses who cared for everyone, whether they were enslaved or free, Christian or Jewish.

During the late 700s and early 800s, Emperor Charlemagne ordered that hospitals that had fallen into disrepair should be fixed. He also said that every cathedral and monastery should have a hospital.

By the 900s, monasteries played a big role in hospital work. The famous Benedictine Abbey of Cluny, founded in 910, was an example for others in France and Germany. Besides caring for their own religious members, each monastery had a hospital for outsiders. These were run by a person called the eleemosynarius, who was in charge of helping visitors and patients.

The eleemosynarius had to find the sick and needy nearby, so each monastery became a place for helping those who suffered. Many monasteries, like those of the Benedictines and Cistercians, were known for this work.

Church leaders also made sure that hospitals were connected to churches in cities. Bishops like Heribert in Cologne and Godard in Hildesheim founded hospitals. Between 1207 and 1577, over 150 hospitals were founded in Germany.

The Ospedale Maggiore in Milan, Italy, was a very large community hospital built in 1456. It was one of the first examples of Renaissance architecture in the region.

When the Normans conquered England in 1066, they brought their hospital system. These new charitable houses became popular and were different from English monasteries and French hospitals. They gave out help and some medicine. Rich people often gave money to these hospitals, hoping for spiritual rewards after death.

The Catholic Church in Europe provided many services that are now handled by governments. It ran hospitals for the elderly, orphanages for children, hospices for the sick, and places for people with leprosy. It also provided food during famines and to the poor. The church paid for this by collecting taxes and owning large farms.

Women's Roles in Healing

Catholic women played a big part in health and healing in medieval and early modern Europe. Becoming a nun was a respected role. Wealthy families gave money to convents for their daughters, and these convents then provided free nursing care for the poor.

In Catholic countries like France, rich families continued to fund convents and monasteries. Their daughters became nuns who offered free health services to the poor. For these nurses, caring for others was a religious duty, and there wasn't much focus on science.

Middle Eastern Nursing

The Eastern Orthodox Church had many hospitals in the Middle East. After the rise of Islam in the 600s, Arabic medicine grew in this region. Many important advances were made, and an Islamic tradition of nursing began. Arab ideas later influenced Europe. The famous Knights Hospitaller started as a group connected to a hospital in Jerusalem. This hospital cared for poor, sick, or injured Christian pilgrims. After Crusaders captured the city, the order became both a military and a nursing group.

Catholic groups like the Franciscans focused on caring for the sick, especially during terrible plagues.

Early Modern Nursing

Catholic Nursing in Europe

Catholic leaders provided hospital services because they believed that faith and good actions led to heaven. This belief is still strong today. In Catholic areas, the tradition of nursing sisters continued without interruption. Several groups of nuns provided nursing in hospitals. The Daughters of Charity of Saint Vincent de Paul, founded in France in 1633, were very important leaders. New groups of Catholic nuns expanded their work and reached new places. For example, in rural France, the Daughters of the Holy Spirit, created in 1706, played a central role.

Wealthy nobles also created new opportunities for nuns to do charity work on their own lands. The nuns gave full care to the sick poor on these estates. They acted not only as nurses but also as doctors, surgeons, and pharmacists. French Catholics in New France (Canada) and New Orleans continued these traditions. During the French Revolution, most nursing orders were closed, and there was no organized nursing to replace them. However, people still needed their nursing services. After 1800, the sisters returned and continued their work in hospitals and on rural estates. Government officials allowed them because they had wide support and helped connect doctors with peasants who needed care.

Protestantism and Hospitals

Protestant reformers, led by Martin Luther, believed that people could not earn God's favor by giving money to charity. They also rejected the idea that poor patients earned salvation through suffering. Protestants generally closed all convents and most hospitals. They sent women home to be housewives, often against their will. However, local officials understood the importance of hospitals. Some hospitals continued in Protestant lands, but without monks or nuns, and were controlled by local governments.

In London, the king allowed two hospitals to continue their charity work under city control. All convents were closed. However, some women, including former nuns, became part of a new system that provided important medical services outside of families. They were hired by churches, hospitals, and private families. They provided nursing care, as well as some medical, pharmacy, and surgical services.

In the 1500s, Protestant reformers closed most monasteries and convents. Nuns who had been nurses were given money or told to get married. Between 1600 and 1800, Protestant Europe had some notable hospitals, but no regular nursing system. Women's public roles were limited, so female healers mostly helped neighbors and family without pay or recognition.

Modern Nursing Begins

Modern nursing started in the 1800s in Germany and Britain. By 1900, it had spread around the world.

The Deaconess Movement

Phoebe, the nurse mentioned in the New Testament, was a deaconess. This role almost disappeared for centuries. But it was brought back in Germany in 1836 by Theodor Fliedner and his wife Friederike Münster. They opened the first deaconess motherhouse in Kaiserswerth. This model soon came to England and Scandinavia. These women promised to serve for five years. They received a place to live, food, uniforms, pocket money, and lifelong care. By 1890, there were over 5,000 deaconesses in Protestant Europe.

William Passavant brought the first four deaconesses to Pittsburgh, USA, in 1849 after visiting Kaiserswerth. They worked at the Pittsburgh Infirmary. Between 1880 and 1915, 62 training schools for deaconesses opened in the United States. However, it became harder to find new deaconesses after 1910. Women preferred nursing schools or social work programs at universities.

Florence Nightingale's Impact

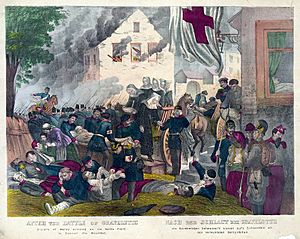

The Crimean War was a very important time for nursing history. English nurse Florence Nightingale created the basic rules for professional nursing. She wrote about these rules in her book Notes on Nursing. Nightingale arrived in Crimea in 1855 and became known as "The Lady with the Lamp." She visited and cared for wounded soldiers all day and night.

At Scutari, the British hospital base, she found terrible conditions and a lack of cleanliness. The hospital was dirty and full of rats. Supplies, food, and even water were scarce. Nightingale organized the cleaning of the entire hospital. She ordered supplies and started hygienic practices like hand washing to stop infections. Many believe Nightingale greatly reduced the death rate at the hospital because she pushed for proper supplies and clean procedures.

In 1855, people raised money for Florence Nightingale and her nurses. With this money, Nightingale decided to start a training school at St Thomas' Hospital in 1860. The first group of nurses graduated from this school and were called 'Nightingales'. Nightingale's friend, Mary Seacole, was a Jamaican "doctress" who also nursed soldiers in the Crimean War. Seacole practiced good hygiene, which Nightingale later wrote about.

Nightingale's reports about the terrible nursing care in the Crimean War inspired reformers. Queen Victoria ordered a hospital to be built in 1860 to train Army nurses and surgeons. This was the Royal Victoria Hospital, which opened in 1863. Nurses were formally assigned to Military General Hospitals starting in 1866. The Army Nursing Service (ANS) began overseeing nurses' work in 1881. These military nurses were sent overseas, starting with the First Boer War (1879-1881). They also served in Egypt in 1882 and Sudan from 1883 to 1884. During the second Boer War (1899-1902), almost 2000 nurses served, including nurses from Australia, Canada, and New Zealand. Twenty-three British Army Nursing sisters died from disease outbreaks.

Nursing Around the World

New Zealand

New Zealand was the first country to officially regulate nurses across the whole country. They passed the Nurses Registration Act 1901 on September 12, 1901. Ellen Dougherty became the first registered nurse in New Zealand.

Canada

Canadian nursing began in 1639 in Quebec with the Augustine nuns. They opened a mission to care for patients' spiritual and physical needs. This mission created the first nursing apprenticeship training in North America.

In the 1800s, some Catholic nursing orders spread across Canada. These women often worked without much input from doctors. By the late 1800s, hospital care and medical services improved. Much of this was thanks to the Nightingale model, which became popular in English Canada. In 1874, the first formal nursing training program started at the General and Marine Hospital in St. Catharines, Ontario. Many similar programs soon appeared across Canada. Nurses who graduated from these programs fought for licensing laws, nursing journals, university training, and professional organizations for nurses.

Canadian nurses first helped the military in 1885 during the North-West Rebellion. In 1901, Canadian nurses officially became part of the Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps. Georgina Fane Pope and Margaret C. MacDonald were the first nurses officially recognized as military nurses.

Canadian missionary nurses were also very important in Henan, China, starting in 1888.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, women entered many professions like teaching, journalism, social work, and public health. A Women's Medical College opened in Toronto in 1883, partly due to Emily Stowe, Canada's first female doctor. Stowe's daughter, Augusta Stowe-Gullen, was the first woman to graduate from a Canadian medical school.

Most women were not part of the male-dominated medical profession. As doctors became more organized, they passed laws to control medicine and pharmacy, banning traditional healers. Midwifery, often practiced by women, was limited and almost disappeared by 1900. Still, most births happened at home until the 1920s, when hospitals became more popular, especially for educated women who trusted modern medicine.

Prairie Provinces

In the Canadian Prairies, early settlers often had to care for themselves. Because of poverty and isolation, women learned to use herbs, roots, and berries for medical care. They also used traditional remedies. This reliance on home remedies continued even as trained nurses and doctors slowly reached the settlers in the early 1900s.

After 1900, medicine and nursing became more modern and organized.

The Lethbridge Nursing Mission in Alberta was a good example of a Canadian volunteer mission. It was founded in 1909 by Jessie Turnbull Robinson, a former nurse. The mission provided nursing services to poor women and children. It was run by a volunteer board of women and raised money through donations. The mission also combined social work with nursing, helping with unemployment relief.

In Alberta, there were differences between the Alberta Association of Graduate Nurses (AAGN) and the United Farm Women of Alberta (UFWA) about midwifery. The UFWA leaders wanted to improve the lives of rural women. They pushed for a provincial Department of Public Health and for nurses to be allowed to be registered midwives. The AAGN disagreed, saying nursing training didn't include midwifery. In 1919, the AAGN and UFWA worked together to pass the Public Health Nurses Act. This law allowed nurses to work as midwives in areas without doctors. So, Alberta's District Nursing Service, created in 1919, was mainly due to the political efforts of UFWA members.

The Alberta District Nursing Service provided health care in rural and poor areas of Alberta in the first half of the 1900s. It was founded in 1919 to help with maternal and emergency medical needs. Nurses provided prenatal care, worked as midwives, did minor surgery, checked schoolchildren's health, and ran immunization programs. After World War II, oil and gas were discovered, bringing wealth and more local medical services. The District Nursing Service was eventually phased out in 1976.

Recent Trends

After World War II, the health care system grew and became nationalized with Medicare. Today, there are about 260,000 nurses in Canada. They face challenges as technology advances and the aging population needs more nursing care.

Mexico

During most of Mexico's wars in the 1800s and early 1900s, women called soldaderas nursed wounded soldiers. During the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920), soldiers in northern Mexico were also cared for by the Neutral White Cross. This group was founded by Elena Arizmendi Mejia after the Mexican Red Cross refused to treat revolutionary soldiers. The Neutral White Cross treated soldiers no matter which side they fought for.

France

Nursing became a professional job in France in the late 1800s and early 1900s. In 1870, France had 1,500 hospitals run by 11,000 Catholic sisters. By 1911, there were 15,000 nuns from over 200 religious groups. After 1900, the government wanted to make public institutions non-religious and reduce the role of the Catholic Church. The number of non-religious staff grew from 14,000 in 1890 to 95,000 in 1911. This goal conflicted with the need for good medical care in old facilities. Many doctors, even if they didn't like the church, knew they depended on the Catholic sisters. Most non-religious nurses came from poor families and were not well trained. They often left the job because of long hours and low pay. Catholic sisters, however, saw nursing as their religious calling and stayed. New government nursing schools trained non-religious nurses for leadership roles. During World War I, many untrained middle-class women volunteered in military hospitals. They left after the war, but their service helped raise the importance of nursing. In 1922, the government created a national nursing diploma.

United States

Nursing quickly became a professional field in the late 1800s. Larger hospitals started nursing schools that attracted ambitious women. Agnes Elizabeth Jones and Linda Richards set up good nursing schools in the U.S. and Japan. Linda Richards was America's first professionally trained nurse. She trained at Florence Nightingale's school and graduated in 1873 from the New England Hospital for Women and Children in Boston.

In the early 1900s, the nursing schools run by nurses themselves, like Nightingale's, ended. Even though universities like Columbia and Yale started nursing schools, hospital training programs were still most common. Formal "book learning" was not encouraged. Instead, students learned by working in hospitals, almost like apprentices. To meet the growing demand, hospitals used student nurses as cheap labor, which sometimes meant less focus on their education.

Jamaica

Mary Seacole came from a long line of Jamaican nurses, or "doctresses." These women healed British soldiers and sailors at the Jamaican military base of Port Royal. In the 1700s, these doctresses used good hygiene and herbal remedies. Seacole's mother, a mixed-race woman, learned about herbal remedies from her West African ancestors. Other 18th-century doctresses included Sarah Adams and Grace Donne. Another doctress, Cubah Cornwallis, nursed famous sailors like the young Horatio Nelson back to health.

Hospitals in the U.S.

The number of hospitals in the U.S. grew from 149 in 1873 to 4,400 in 1910, and to 6,300 in 1933. This happened because people trusted hospitals more and could afford better care.

Hospitals were run by cities, states, federal agencies, churches, non-profit groups, and private doctors. All major religious groups built hospitals. In 1915, the Catholic Church ran 541 hospitals, mostly staffed by unpaid nuns. Other hospitals sometimes had a few deaconesses as staff. Most larger hospitals had nursing schools, which trained young women who then did much of the unpaid work. The number of active graduate nurses grew quickly from 51,000 in 1910 to 375,000 in 1940, and 700,000 in 1970.

Protestant churches also re-entered the health field. They set up groups of women, called deaconesses, who dedicated themselves to nursing.

The modern deaconess movement began in Germany in 1836. Theodor Fliedner and his wife opened the first deaconess motherhouse in Kaiserswerth. This became a model, and within 50 years, there were over 5,000 deaconesses in Europe. The Church of England named its first deaconess in 1862.

William Passavant brought the first four deaconesses to Pittsburgh, in the United States, in 1849. They worked at the Pittsburgh Infirmary.

The American Methodists, the largest Protestant group, started large missionary work in Asia and other parts of the world. They made medical services a priority as early as the 1850s. Methodists in America began opening their own charities like orphanages and homes for the elderly after 1860. In the 1880s, Methodists started opening hospitals in the United States that served people of all religions. By 1895, 13 hospitals were operating in major cities.

In 1884, U.S. Lutherans brought seven sisters from Germany to run the German Hospital in Philadelphia.

By 1963, the Lutheran Church in America had centers for deaconess work in Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Omaha.

Public Health Nursing

In the U.S., the role of public health nurse began in Los Angeles in 1898. By 1924, there were 12,000 public health nurses, with half of them in the 100 largest cities. Their average yearly salary in bigger cities was $1,390. Thousands more nurses worked for private agencies doing similar work. Public health nurses oversaw health issues in schools, provided prenatal and infant care, handled infectious diseases, and dealt with other illnesses.

During the Spanish–American War of 1898, conditions in the tropical war zone were dangerous, with diseases like yellow fever common. The U.S. government asked women to volunteer as nurses. Thousands did, but few were professionally trained. Among them were 250 Catholic nurses, mostly from the Daughters of Charity of Saint Vincent de Paul.

Nursing Schools Today

Progress in nursing schools happened in many parts of the world, where medical pioneers set up formal nursing schools. But even in the 1870s, "women working in North American city hospitals were usually untrained, working class, and not highly respected." Nursing had a similar status in Great Britain and Europe before World War I.

Hospital nursing schools in the United States and Canada led the way in using Nightingale's model for their training programs. Standards for classroom and on-the-job training greatly improved in the 1880s and 1890s. Along with this, expectations for proper and professional behavior also rose.

In the late 1920s, women's health care jobs included 294,000 trained nurses, 150,000 untrained nurses, 47,000 midwives, and 550,000 other hospital workers (mostly women).

In recent years, nursing degrees have moved from hospital schools to community colleges and universities. Specialization has led to many journals that help nurses learn more about their profession.

World War I Nursing

Britain

At the start of World War I, military nursing in Britain still had a small role for women. About 10,500 nurses joined the Queen Alexandra's Imperial Military Nursing Service (QAIMNS) and the Princess Mary's Royal Air Force Nursing Service. These services began in 1902 and 1918 and had royal support. There were also Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) nurses who were part of the Red Cross. New ranks were created for nurses: Matron-in-Chief, Principal Matron, Sister, and Staff Nurses. Women steadily joined throughout the War. By the end of 1914, there were 2,223 regular and reserve QAIMNS members. When the war ended, there were 10,404 trained nurses in the QAIMNS.

Grace McDougall (1887–1963) was the energetic leader of the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry (FANY). This group formed in 1907 to help the home guard in Britain. McDougall was once captured by the Germans but escaped. The British army didn't want them, so they drove ambulances and ran hospitals for the Belgian and French armies.

Canada

When Canadian nurses volunteered for World War I, they were made commissioned officers by the Canadian Army before being sent overseas. This gave them authority, so patients and orderlies had to follow their directions. Canada was the first country to give women this privilege. At first, nurses were not sent to casualty clearing stations near the front lines, where they would be in danger. They were assigned to hospitals a safe distance away. However, as the war continued, nurses were assigned to these stations. They faced shelling and cared for soldiers with "shell shock" and injuries from new weapons like poisonous gas. World War I was also the first war where clearly marked hospital ships were targeted and sunk by enemy submarines. Nurses were among the casualties.

Canadian women eager to serve as nurses overseas sent many applications to the army. A total of 3,141 Canadian "nursing sisters" served in the Canadian Army Medical Corps. Of these, 2,504 served overseas in England, France, and the Eastern Mediterranean. By the end of World War I, 46 Canadian Nursing Sisters had died. Other nurses volunteered and paid their own way with groups like the Canadian Red Cross and the Victorian Order of Nurses. The sacrifices these nurses made during the War helped the women's right to vote movement in many countries. Canadian Army nursing sisters were among the first women in the world to win the right to vote in a federal election.

Australia

Australian nurses served in World War I as part of the Australian General Hospital. Australia set up two hospitals on Lemnos and Heliopolis Islands to support the Gallipoli campaign. Nursing recruitment was not always organized. Some nurses were sent with advance groups, while others simply showed up and were accepted. Australian nurses from this time were known as "grey ghosts" because of their plain uniforms.

During the war, Australian nurses were given their own administration, meaning they didn't work directly under medical officers. Australian Nurses hold the record for the most triage cases handled by a casualty station in 24 hours during the Battle of Passchendaele. Their work included giving ether during surgery and managing medical assistants.

About 560 Australian army nurses served in India during the war. They had to deal with a difficult climate, disease outbreaks, not enough staff, overwork, and difficult British Army officers.

Between the World Wars

Surveys in the U.S. showed that nurses often got married a few years after graduating and stopped working. Others waited 5 to 10 years to marry. Some career nurses never married. By the 1920s, more married nurses continued to work. The high number of nurses leaving meant that promotions could happen quickly. The average age of a nursing supervisor in a hospital was only 26 years old. Wages for private duty nurses were high in the 1920s, about $1,300 a year for full-time work. This was more than double what a woman could earn as a teacher or office worker. Rates dropped sharply when the Great Depression began in 1929, and it became much harder to find steady work.

World War II Nursing

Canada

Over 4,000 women served as nurses in uniform in the Canadian Armed Forces during World War II. They were called "Nursing Sisters" and were already professionally trained. In military service, they gained a higher status than they had as civilians. Nursing Sisters had more responsibility and freedom. They were often close to the front lines. Military doctors, who were all men, gave nurses a lot of responsibility because there were many casualties, few doctors, and extreme working conditions.

Australia

In 1942, 65 front-line nurses from the General Hospital Division in British Singapore were ordered to evacuate on the ships Vyner Brook and Empire Star. The ships were attacked by Japanese planes. Sisters Vera Torney and Margaret Anderson were given medals because they covered their patients with their own bodies to protect them. The Vyner Brook was bombed and sank quickly. All but 21 nurses were lost at sea. The remaining nurses swam ashore at Mentok, Sumatra. These 21 nurses and some British and Australian troops were marched into the sea and killed by machine gun fire in the Bangka Island massacre. Sister Vivian Bullwinkel was the only survivor. She became Australia's main nursing war hero. She nursed wounded British soldiers in the jungle for three weeks, even though she was also wounded. She survived with help from Indonesian locals, but eventually had to surrender. She remained imprisoned for the rest of the war.

Around the same time, another group of 12 nurses at the Rabaul mission in New Guinea were captured by Japanese troops. They were held in a camp for two years and cared for British, Australian, and American wounded. Towards the end of the war, they were moved to a concentration camp in Kyoto. There, they were imprisoned in freezing conditions and forced into hard labor.

United States

The nursing profession changed greatly during World War II. Joining the Army and Navy nursing services was very appealing. A higher percentage of nurses volunteered for service than any other job in American society.

The public saw nurses very positively during the war. Hollywood films showed selfless nurses as heroes under enemy fire. Some nurses were captured by the Japanese, but usually, they were kept out of direct danger. Most nurses were stationed at home. However, 77 nurses were in the Pacific jungles, where their uniform was "khaki slacks, mud, shirts, mud, field shoes, mud, and fatigues." The medical services were huge, with over 600,000 soldiers and ten enlisted men for every nurse. Almost all doctors were men.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt praised nurses' service in the war in his last "Fireside Chat" in January 1945. Expecting many casualties in the invasion of Japan, he called for a required draft of nurses. However, the casualties never happened, and American nurses were never drafted.

Britain

During World War II, nurses belonged to Queen Alexandra's Imperial Military Nursing Service (QAIMNS), just as they had in World War I. They still do today. (Nurses in the QAIMNS are often called "QAs.") Members of the Army Nursing Service served in every British military campaign overseas during World War II, as well as in military hospitals in Britain. At the start of World War II, nurses had officer status, meaning they had the same rank, but they were not commissioned officers. In 1941, emergency commissions and a rank system were created, matching the rest of the British Army. Nurses were given rank badges and could be promoted from Lieutenant to Brigadier. Nurses faced all the dangers of the War, and some were captured and became prisoners of war.

Germany

Germany had a very large and well-organized nursing service. It had three main groups: one for Catholics, one for Protestants, and the DRK (Red Cross). In 1934, the Nazis created their own nursing unit, the Brown Nurses. This group grew to 40,000 members. It set up kindergartens, hoping to control the minds of younger Germans, competing with other nursing groups. Civilian psychiatric nurses who were Nazi party members took part in killing invalids, though this process was hidden behind vague words.

Military nursing was mainly handled by the DRK, which came partly under Nazi control. Male medics and doctors provided front-line medical services. Red Cross nurses worked widely in military medical services, staffing hospitals close to the front lines that were at risk of bombing. Two dozen nurses received the highly respected Iron Cross for bravery under fire. They were among the 470,000 German women who served with the military.

See also

In Spanish: Anexo:Cronología de la enfermería para niños |

In Spanish: Anexo:Cronología de la enfermería para niños |

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |