History of the Cape Colony from 1870 to 1899 facts for kids

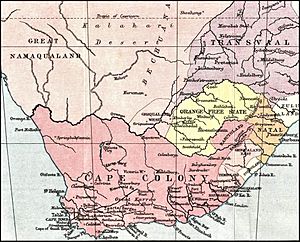

The year 1870 was a big turning point for the Cape Colony in South Africa. It was like the start of modern South Africa! Even with some political challenges, the region grew steadily until the Anglo-Boer Wars began in 1899.

A huge discovery happened in 1867: diamonds were found in the Orange River. Soon after, more diamonds appeared in the Vaal River. This led to many people moving into and developing large areas that were mostly empty before. In 1870, the Dutoitspan and Bultfontein diamond mines were found. Then, in 1871, even richer mines like Kimberley and De Beers were discovered. These four amazing diamond areas produced a lot of wealth and became the Colony's most important industry.

During this time, there was also growing tension between the English-controlled Cape Colony and the Afrikaner-controlled Transvaal. These disagreements eventually led to the First Boer War. The main reasons for these tensions were about making trade easier between the different colonies and building new railways.

Contents

Life in the Cape Colony

Before the diamond industry started, all of South Africa was going through a tough economic time. Ostrich farming was just beginning, and farming in general wasn't very developed. Many Boers, especially those far from Cape Town, lived in poor conditions. They didn't trade much with the Colony. Even British colonists weren't very rich.

So, the diamond industry was very exciting, especially for British colonists. It showed that South Africa, which looked dry and poor on the surface, was actually rich underground. Imagine, a small area of diamond-rich ground could support many families! By the end of 1871, lots of people had moved to the diamond fields. Many newcomers arrived, hoping to find their fortune. One of the first to seek wealth there was Cecil Rhodes.

The Start of Self-Rule

In 1872, the Cape Colony gained "responsible government". This meant its government ministers would now answer to the locally elected Cape Parliament, not just the British Governor. Before this, the British Governor had more direct control.

A popular movement, led by John Molteno, had been pushing for this change since the early 1860s. They wanted the government to be accountable to the people and their elected representatives. This would give the Cape Colony more independence from Britain.

For much of the 1860s, there was a political struggle between the British Governor, Sir Philip Wodehouse, and the movement for self-rule. This political problem also led to economic problems and disagreements between different parts of the Cape.

Finally, in 1872, with the support of a new Governor, Henry Barkly, Molteno succeeded. Ministers became responsible to Parliament, and Molteno became the Cape's first Prime Minister. The years that followed saw quick economic growth, new buildings and roads across the country, and better connections between different regions.

Even though wars soon interrupted this peace, the Cape Colony kept its responsible government until it became the Cape Province in the new Union of South Africa in 1910. An important thing about the Cape's political system was that it was the only state in southern Africa to have a voting system that wasn't based on race. However, after the Act of Union of 1910, this multi-racial voting right was slowly taken away and finally removed by the Apartheid government in 1948.

A Failed Plan for Unity

The idea of joining the states of southern Africa into a Confederation wasn't new. An earlier plan by Sir George Grey in 1858 was rejected by Britain. Later, Lord Carnarvon, who was in charge of the colonies, tried again. He had successfully united Canada and wanted to do the same in Southern Africa.

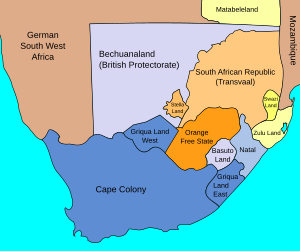

Southern Africa was important for the British Empire's safety, but it wasn't fully under British control. Some Black African and Boer states were still independent, and the Cape Colony had just gained some self-rule. Lord Carnarvon believed that uniting these states under British rule would be the best way to gain control with less conflict. However, forcing this union on Southern Africa caused a lot of anger. This led to serious conflicts like the Anglo-Zulu War and the First Boer War.

Wars and Their Impact

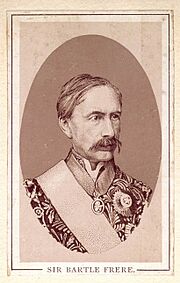

The Transvaal was taken over by the British in 1877. Other independent African kingdoms were also brought under British control. With the Cape government's power reduced, Sir Henry Bartle Frere, a British official, turned his attention to the Zulu Kingdom. He believed the Zulu army needed to be defeated to bring them into the planned Confederation.

Frere sent a challenging message to the Zulu King, Cetshwayo, in December 1878. Cetshwayo could not agree to the demands, so Frere ordered an invasion of Zululand. This started the Anglo-Zulu War. The war began badly for the British with the disaster at Isandlwana.

Meanwhile, the Boers in the Transvaal were also unhappy. The British had promised them a new government, but it was delayed. This made the Boers, who were a growing group, very angry. The British loss at Isandlwana also made them seem weaker. Eventually, the Boers rebelled, leading to the First Boer War (1880–1881). This war resulted in the Boer republics regaining their independence.

During these wars, Lord Carnarvon resigned, and his plan for a confederation was dropped.

Results of the Confederation Wars

Lord Carnarvon didn't understand that Southern Africa was very different from Canada. His plan caused more problems than it solved. It made the relationships between the different states in Southern Africa even more difficult.

New unrest spread among the Xhosa tribes. There was also an uprising in Basutoland under Moirosi. The Xhosa under Moirosi were defeated, but the Basotho people remained restless. In 1880, the British tried to take away the Basotho's weapons, leading to more fighting. Eventually, the British government took over Basutoland as a crown colony.

Sir Bartle Frere was called back to Britain in 1880. Sir Hercules Robinson took his place. Griqualand West, which included most of the diamond fields, became part of the Cape Colony.

A lasting result of these wars was the increased bad feelings between the Boers and the British in southern Africa. These feelings later contributed to the much bigger Second Boer War.

The Afrikander Bond

The end of the First Anglo-Boer War in 1881 had a big impact across South Africa. One important result was the first meeting of the Afrikander Bond in 1882. This group grew to include members from the Transvaal, the Orange Free State, and the Cape Colony.

The Bond's main goal was to create a South African identity and a love for their homeland. A newspaper that supported the Bond, De Patriot, wrote: "The Afrikander Bond wants to create a South African nation by spreading a true love for our fatherland. There's no better time than now, after the Transvaal war, when the feeling of being a nation has truly awakened."

The newspaper also suggested that the British should only keep Simon's Bay as a naval base and give the rest of South Africa to the Afrikaners. It encouraged Afrikaners to support their own businesses and avoid spending money with English traders.

While the Bond's official statements were sometimes milder, their original plan included a goal of complete independence for South Africa. This was seen by some as an act against the British Crown.

However, the Bond's ideas also made other people feel more loyal to Britain. A pamphlet from 1885 argued that British rule had been good for everyone and that leaving Britain would be disastrous. It encouraged colonists to unite under the British flag and work together for a prosperous future.

From 1881 onwards, two main political ideas grew in the Cape Colony. One, supported by people like Cecil Rhodes, wanted the British Empire to expand into independent Southern African states. They also wanted civil rights for "civilized" people, regardless of their background, under British protection. The other idea was for a self-governing, but mainly Dutch, South Africa. The extreme supporters of this idea wanted a united South Africa completely free from British rule.

The founders of the Bond were Carl Borckenhagen and Reitz. Conversations with them showed their true aims. Borckenhagen told Cecil Rhodes, "We want a united Africa." Rhodes agreed, but when Borckenhagen added, "We must, of course, be independent of the rest of the world," Rhodes disagreed. He said he wouldn't betray his own country. Rhodes believed that a true union needed the protection of a strong power like Britain.

Another conversation happened when the Bond was being formed. Reitz told T. Schreiner that the Bond aimed to remove British rule. When Schreiner said this would lead to a huge struggle, Reitz replied, "What of that?" This showed that from the very beginning, the Bond's main goal was an independent South Africa.

Rhodes and Dutch Relations

Cecil Rhodes understood the challenges of his position. From the start of his political career, he tried to work well with the Dutch. He was elected to the House of Assembly in 1880. In 1882, he supported a law that allowed Dutch to be used in the Assembly. In 1884, he became treasurer-general.

Rhodes's attempts to get along with the Boers didn't always work. In 1885, more areas were added to the Cape Colony, including Tembuland, Bomvanaland, and Galekaland. Sir Gordon Sprigg became prime minister in 1886.

South African Customs Union

There was a lot of unrest in the Cape Colony between 1878 and 1885. This was partly due to the British trying to force a confederation system, similar to Canada, on Southern Africa. This period saw the Anglo-Zulu War, problems with the Basutos, and conflicts with the Xhosa, followed by the First Boer War of 1881.

Despite these difficulties, the country continued to grow. The diamond industry was doing very well. In 1887, a conference was held in London to discuss closer ties within the British Empire through trade rules. A proposal was made for a "Zollverein" (a customs union) to promote unity and raise money for defense. This idea wasn't put into practice at the time, but it showed a positive view of the proposal's supporter, Hofmeyr.

Even though the political confederation failed, the Cape parliament worked to create a South African Customs Union in 1888. A law was passed, and soon after, the Orange Free State joined. There were many attempts to get the Transvaal to join, but President Kruger wanted the Transvaal to be completely independent of the Cape Colony. He was focused on his own railway plans, which would connect the Transvaal to Delagoa Bay.

Diamonds and Railways

Another very important event for the Cape Colony, and all of South Africa, was the joining together of the diamond-mining companies in 1889. This was mainly thanks to Cecil Rhodes, Alfred Beit, and "Barney" Barnato. One of the best results of the diamond discoveries was how much it boosted railway building.

New railway lines were opened to many towns, and Kimberley was reached in 1885. By 1890, the line stretched northwards into British Bechuanaland. In 1889, the Free State agreed with the Cape Colony to extend the main railway line to Bloemfontein. The Free State later bought the part of the railway in its own territory. By 1892, the railway reached Pretoria and Johannesburg.

Rhodes as Prime Minister

In 1890, Cecil Rhodes became the Prime Minister of the Cape Colony. He had a good relationship with many Dutch people, and his ideas for customs and railway unions between the different states helped him lead the government successfully.

The colonies of British Bechuanaland and Basutoland were included in the customs union with the Orange Free State and Cape Colony. Pondoland, another native territory, was added to the colony in 1894. A law was passed that helped native people living in certain reserves. It gave them new rights and required them to pay a small labor tax. This was considered a very important law for native affairs. Rhodes reported in 1895 that the law applied to 160,000 native people.

Rhodes's approach to native policy combined care and firmness. Since gaining self-government, native people had the right to vote. However, a law passed in 1892, pushed by Rhodes, added an education test for voters and other limits. This was because some worried that "tribal" natives might threaten the government system.

Rhodes also worked to stop the illegal trade of alcohol. He completely stopped it on the diamond mines, even though it upset some of his supporters who were brandy farmers. He also limited it as much as possible in native reserves.

One example of Rhodes's understanding of native affairs was his action in an inheritance case. After new territories were added to the Cape Colony, a court ruled that the eldest son of a native man was his heir, following colonial law. However, this went against native tribal law, which recognized the son of the chief wife as the heir. This caused anger among the native people. Rhodes quickly promised that the decision would be changed and that native laws would be respected. This helped restore peace.

Later, Rhodes introduced a short law that allowed civil cases for native people to be heard by magistrates, following native law. This meant that native marriage customs and laws, including polygamy, became legal in the colony.

Sir Hercules Robinson became governor again in 1895, and Joseph Chamberlain became the British Secretary of State for the Colonies.

Push for Trade Unity

As railways grew and trade increased between the Cape Colony and the Transvaal, politicians started discussing closer ties. While Prime Minister, Rhodes tried to create a friendly trade union among the states of South Africa. He hoped for both a trade and a railway union. In 1894, he said he could understand why republics wanted to be independent, but he believed they could still share common principles like tariffs, railway connections, and laws, similar to the United States.

President Kruger and the Transvaal government strongly opposed this idea. Their actions in what was called the Vaal River Drift Question showed their approach. There were disagreements over a railway agreement. The Cape government had helped fund a railway extension to Johannesburg. But in 1895, the Netherlands railway, which controlled part of the line, greatly increased its prices.

President Kruger wanted traffic to use the railway line to Delagoa Bay instead of the colonial railway. To avoid the high prices, Johannesburg merchants started moving their goods across the Vaal River using wagons. In response, President Kruger closed the river crossings (drifts), blocking the wagon traffic. This caused a huge pile-up of wagons. The Cape government protested, saying it broke an agreement called the London Convention.

President Kruger didn't change his mind. So, the Cape government asked the British government for help. Britain agreed to protest if the Cape would share costs and provide troops if needed. Rhodes agreed, and Britain sent a strong message to President Kruger, calling his actions "unfriendly." President Kruger immediately reopened the crossings.

In December 1895, Leander Starr Jameson led a famous raid into the Transvaal. Rhodes was involved in this plan, which forced him to resign as Prime Minister in January 1896. Sir Gordon Sprigg took his place. When Rhodes's involvement became known, his colleagues were shocked and angry. The Bond and Hofmeyr strongly criticized him. This made the Dutch people in the Cape Colony even more resentful towards the English, which affected their later views on the Transvaal Boers.

There was another native uprising in Griqualand West in 1897, led by a Bantu chief named Galeshwe. He was arrested, and the rebellion ended. Galeshwe claimed a Transvaal magistrate supplied him with weapons and encouraged him to rebel. There was evidence to support this.

Sir Alfred Milner became the new high commissioner and governor of Cape Colony in 1897.

Schreiner's Leadership

Trade unity moved forward in 1898 when Natal joined the customs union. A new agreement was made for a "uniform tariff on all imported goods" and free trade for South African products within the union. Another election in the Cape Parliament in the same year brought in a new Bond-supported government led by W. P. Schreiner. He remained Prime Minister until June 1900.

During the talks before the Second Boer War began in 1899, feelings were very strong in the Cape. As the leader of a party supported by the Bond, Schreiner had to balance many different influences. However, as Prime Minister of a British colony, many loyal colonists felt he should not have openly interfered with the Transvaal and British governments. His public statements seemed to oppose the policies of Chamberlain and Sir Alfred Milner. Some believe Schreiner's public opposition encouraged President Kruger to reject British proposals.

In private, Schreiner tried to convince President Kruger to be more "reasonable." But his public disapproval of British policy might have done more harm than his private efforts did good.

On June 11, 1899, Schreiner told Chamberlain that he and his colleagues accepted President Kruger's proposals as "reasonable." However, later in June, Cape Dutch politicians realized that President Kruger's attitude wasn't as reasonable as they thought. Hofmeyr visited Pretoria and found the Transvaal parliament (Volksraad) defiant.

Hofmeyr, a respected diplomat, tried to convince Kruger to change his plan, but his mission failed. He returned to Cape Town disappointed. Meanwhile, the Boer leaders made a new proposal. Schreiner wrote a letter on July 7, stating that his government believed there was "no ground whatever exists for active interference in the internal affairs of that republic."

This letter proved to be unfortunate. On July 11, after meeting Hofmeyr, Schreiner personally asked President Kruger to be friendly with the British government. Another incident at the same time made public opinion very hostile towards Schreiner. On July 7, 500 rifles and 1,000,000 rounds of ammunition were unloaded at Port Elizabeth and sent to the Free State government. Schreiner knew about this but refused to stop it. He argued that since Britain was at peace with the Free State, he had no right to stop the shipment. However, his inaction earned him the nickname "Ammunition Bill" among British colonists. He was also accused of delaying sending weapons to defend Kimberley, Mafeking, and other towns. He said he didn't expect war and didn't want to make the Free State suspicious. While his actions might have been technically correct, loyal colonists strongly resented them.

Chamberlain sent a message to President Kruger on July 28, suggesting a meeting. On August 3, Schreiner urged the Transvaal to accept Chamberlain's proposal. Later, when the Free State asked about British troop movements, Schreiner refused to give information. On August 28, Sir Gordon Sprigg criticized Schreiner in the House of Assembly for not stopping the arms shipment. Schreiner replied that if trouble arose, the colony would stay out of it. He also read a telegram from President Steyn, who denied any aggressive actions by the Free State. This speech caused a scandal in the British newspapers.

Looking back at Schreiner's actions in late 1899, it's clear he misunderstood the situation in the Transvaal. He didn't fully grasp the complaints of the uitlanders (foreigners) and wrongly believed President Kruger would eventually be fair. Experience should have taught him that President Kruger was unlikely to change his mind, and President Steyn's promises were not sincere.

|

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |