History of the Scots language facts for kids

The history of the Scots language tells us how different types of English spoken in parts of Scotland grew into the modern Scots language we know today.

Contents

How Scots Began

In the 600s, people speaking Northumbrian Old English settled in southeastern Scotland. At that time, other languages were spoken nearby. Cumbric was spoken in southern Scotland. Pictish was spoken further north.

Around the same time, Gaelic speakers started moving from western Scotland towards the east. Over the next 500 years, as Scotland was formed and Christianity spread, Gaelic slowly moved across the lowlands.

When lands from Northumbria became part of Scotland in the 1000s, Gaelic became a very important language there. It influenced the local languages. However, the southeast of Scotland mostly kept speaking English. In the far north, Vikings brought Old Norse to places like Caithness, Orkney, and Shetland.

Experts usually divide the history of Scots into these periods:

- Northumbrian Old English: Up to the year 1100.

- Pre-literary Scots: From 1100 to 1375.

- Early Scots: From 1375 to 1450.

- Middle Scots: From 1450 to 1700.

- Modern Scots: From 1700 onwards.

Early Scots: A New Language Forms

Northumbrian Old English was spoken in southeastern Scotland by the 600s. It stayed mostly in this area until the 1200s. It was commonly used, even though Scottish Gaelic was the language of the royal court. Later, French became the court language in the early 1100s.

After the 1100s, an early form of northern Middle English began to spread north and east. This is where Early Scots started to develop. People who spoke it called it "English" (Inglis). This is why, in the late 1100s, Adam of Dryburgh called his home "in the land of the English in the Kingdom of the Scots."

Most signs suggest that English spread into Scotland through the burghs. These were early towns first set up by King David I. People moving into these towns were mainly English, Flemish, and French. Even though the noble families used French and Gaelic, these small towns seemed to use English as their main language by the late 1200s.

In the 1300s, English became more important. French became less important in Scotland's Royal Court. This made English the most respected language in most of eastern Scotland.

How Early Scots Changed

Early Scots became different from Northumbrian Middle English due to several influences:

- Norse: People from northern and central England who spoke Middle English influenced by Norse moved to Scotland in the 1100s and 1200s.

- Dutch and German: Trade and immigration from the Low Countries brought in words from Dutch and Middle Low German.

- Romance languages: Words came from church and legal Latin, Norman French, and later Parisian French. This was due to the Auld Alliance (Scotland's alliance with France).

Some words also came from Scottish Gaelic. These often described nature, like ben (mountain), glen (valley), crag (rocky hill), loch (lake), and strath (wide valley). Other Gaelic words include bog (wet ground), twig (understand), galore (lots of), boose (mouth), and whisky (water of life).

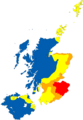

Eventually, the royal court and noble families all spoke Inglis. As the language spread, Scottish Gaelic was mostly spoken in the Highlands and islands by the end of the Middle Ages. However, some lowland areas, like Galloway and Carrick, kept Gaelic until the 1600s or 1700s. From the late 1300s, Inglis even replaced Latin as the language for official documents and literature.

Middle Scots: A New Name

By the early 1500s, what was then called Inglis became the language of government. Its speakers started to call it Scottis. They began to call Scottish Gaelic, which had been called Scottis before, Erse (meaning Irish). The first time this name change is known to have happened was around 1494.

In 1559, William Nudrye was allowed by the court to print school textbooks. Two of these were about learning to read and write the "Scottis Toung." In 1560, an English official spoke to Mary of Guise and her advisors. They first spoke in the "Scottish tongue," but because he could not understand, they switched to French.

By this time, Scots had become quite different from English spoken south of the border. It was used for a rich and varied national literature. Writers had some freedom in how they spelled words. However, they usually kept some consistency.

Scots Becomes More Like English

From the mid-1500s, Scots started to become more like English. When King James I became king, the King James version of the Bible and other Bibles printed in English became very popular. By the late 1500s, almost all writing used a mix of Scots and English spellings. English spellings slowly became more common. By the end of the 1600s, Scots spellings had almost disappeared in written works. This change took a bit longer in private writings and official records.

After the Union of the Crowns in 1603, when Scotland and England shared the same king, Scottish nobles had more contact with English speakers. They began to change their way of speaking to sound more like their English friends. This change eventually led to the creation of Scottish English.

From 1610 to the 1690s, during the Plantation of Ulster, about 200,000 Scots moved to northern Ireland. They took their language, which later became the Ulster Scots dialects, with them. Most of these Scots came from western Scotland. The Ulster-Scots language has been greatly influenced by Hiberno-English (Irish English) in how it sounds. It also has words borrowed from the Irish language.

Modern Scots: Still Evolving

In the 1700s, many polite people thought Scots sounded "country-like and rough." Many wealthy people tried to stop speaking it. Teachers were hired to teach Scots people how to speak "proper" English.

However, not all educated Scots agreed with this view. A new literary Scots began to appear. Unlike Middle Scots, this new style was often based on how people spoke every day. Its spelling usually adapted the English standard. But some older Scots spelling features were still used. Writers like Allan Ramsay and Robert Burns used this modern literary Scots.

Many writers and publishers found it helpful to use English spellings and lots of apostrophes. This helped them reach more English readers who were not familiar with Scots. But the way the words were said was still Scots, as shown by the rhymes in their poems.

In the early 1800s, John Jamieson published his Etymological Dictionary of the Scots Language. This led to new interest in Scots among the middle and upper classes. During this time, there was no official standard way to speak or write Scots. This led to different dialects becoming even more distinct.

Images for kids

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |