Homeric scholarship facts for kids

Homeric scholarship is the study of everything about Homer, especially his two famous long poems, the Iliad and the Odyssey. Today, this study is part of classical studies, which looks at ancient Greece and Rome. Studying Homer is one of the oldest subjects taught in schools!

Contents

Ancient Studies of Homer's Poems

Old Notes and Commentaries: Scholia

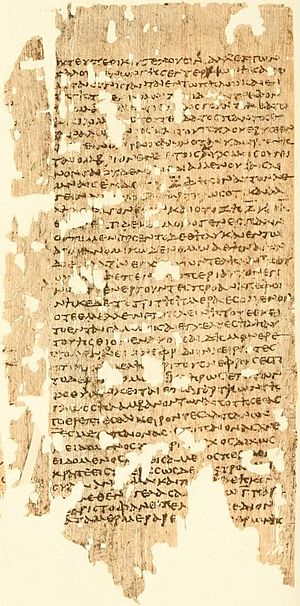

Imagine writing notes in the margins of your textbook. That's what scholia (say: SKOH-lee-uh) were! They were ancient notes and comments written by scholars, usually in the blank spaces around the main text of old handwritten books. Sometimes they were even written between the lines.

Over time, when people copied these old books, they also copied the scholia. If there wasn't enough space, they'd put the notes on separate pages. Today, we have footnotes or endnotes in books, which are a lot like these ancient scholia. Homer's poems have always had many notes written about them, right from the start.

There are about 1,800 copies of the Iliad from ancient times, and many copies of the Odyssey. But not all of them have scholia. No single book has collected all the Homeric scholia ever found.

Scholars have grouped the most important scholia into three main types, named A, bT, and D.

- A-scholia are mostly found in a very important copy of the Iliad called Venetus A. This book was made in the 900s CE and is kept in Venice, Italy. These notes are called "critical" because they often discuss the original text and its meaning.

- bT-scholia come from two other old copies. These notes are more about explaining the meaning of the poems.

- D-scholia are the oldest and largest group of notes. They were once thought to be by a scholar named Didymus, but we now know they come from even older school books from the 400s and 300s BCE. Many of these are like small dictionaries, explaining difficult words. Others explain myths or parts of the story.

The oldest scholia are the D-scholia (from around 400s BCE), followed by A-scholia, then bT-scholia (up to 700s CE). This means people have been studying and writing about Homer for a very long time!

Classical Greek Studies of Homer

By the time of Classical Greece (around 500-300 BCE), people were already asking the "Homeric Question": Which poems did Homer actually write? Everyone agreed he wrote the Iliad and the Odyssey.

The D-scholia show that these poems were taught in schools. But the language of Homer was already old, so the notes helped students understand it.

People believed Homer was a single author, but there were many different versions of his poems. This made them wonder if some parts were fake or added by others.

The Peisistratean Edition

Some ancient writers said that Peisistratos (say: Pie-SIS-trah-tos), a ruler of Athens from 561-527 BCE, or perhaps Solon, an earlier lawgiver, changed parts of the Iliad. For example, they might have changed the "Catalogue of Ships" (a list of ships in the Iliad) to make it seem like Athens owned Salamis Island during the Trojan War. This suggests that Peisistratos or Solon had some power over the main text of the Iliad.

Another writer, Diogenes Laërtius, said that during Solon's time, the Iliad was recited in public by performers called "rhapsodes." Solon even made a law that one rhapsode had to start exactly where the previous one left off. This shows that the government was involved in these performances, which were often part of big festivals.

The Roman writer Cicero said that before Peisistratos, Homer's books were "confused." But Peisistratos "arranged" them into the order they were in during Cicero's time. It seems that shorter poems about the Trojan War were put together into a continuous story, possibly edited by Peisistratos.

Searching for the Standard Text

There's a gap in history between the possible edition by Peisistratos and the standard version of Homer's poems used by later scholars in Alexandria (around 300 BCE). Scholars still don't have a perfect, final version of the Iliad or Odyssey.

Some scholars, like Villoison, thought that the original written copy of Homer's poems was lost. Peisistratos might have offered rewards for verses of Homer, which could have led to fake verses being added. The challenge then was to figure out which verses were real and which were not.

On the other hand, Friedrich August Wolf argued in 1795 that Homer never actually wrote the Iliad down. He believed the different versions seen by later scholars weren't mistakes, but different versions passed down by rhapsodes. The historian Flavius Josephus also said that Homer's poetry was "kept by memory" and "put together later from the songs."

The big missing piece is how the texts supposedly put together by Peisistratos connect to the standard versions used by the Alexandrian scholars.

Scholars and Homer's Text

Plato quoted Homer more than any other ancient writer, using 209 lines. Aristotle quoted 93 lines. Most of Plato's quotes match the standard version of Homer's poems very closely. This suggests that the copy Plato used was very "pure" and not mixed with other versions.

Plato had a special view of Homer. He thought Homer's myths were like allegories, meaning they had a deeper, hidden truth. But in his book Republic, Plato said that children can't tell the difference between literal stories and allegories. So, he suggested that myth-makers, including Homer, should be censored (meaning parts of their stories should be removed or changed) in his ideal society. This idea wasn't very popular.

Aristotle's Influence

The first big library in the ancient Greek world was at the Lyceum in Athens, founded by Aristotle. Aristotle was a student of Plato. Later, he became the teacher of Alexander the Great.

Alexander loved Homer's poems. He even kept a copy of Homer's Iliad that Aristotle had personally edited for him. This special copy was so important that Alexander kept it in an expensive box he took from the Persian king. This story shows that Aristotle and his group believed there was a true, original text of Homer, and they tried to restore it.

Aristotle studied Homer in a different way than Plato. He looked at Homer's language and problems in the text. He even wrote a book called "Six books of Homeric problems," though it doesn't survive today.

Hellenistic Scholars and Their Goals

Many ancient Greek writers talked about Homer's poems. But serious scholarship focused on three main goals:

- Finding parts of the poems that didn't seem to fit together.

- Creating the most accurate versions of the poems, without mistakes or added parts.

- Explaining old words and interpreting the poems' meaning.

One of the first philosophers to really dig into problems with Homer's poems was Zoilus in the 300s BCE. He pointed out inconsistencies, like how a character named Pylaemenes is killed in one part of the Iliad but appears alive later. These moments are sometimes called "Homeric nods," like Homer "nodded off" or made a mistake. Aristotle's lost book, "Homeric Problems," was probably a response to Zoilus.

Two very important scholars from Alexandria, Zenodotus of Ephesus (say: Zeh-NOH-duh-tus) and Aristarchus (say: Ah-ris-TAR-kus), created important editions of Homer's poems in the 200s BCE. Zenodotus might have been the first to divide the Iliad and Odyssey into 24 books each.

Aristarchus's edition was probably the most important in the history of Homeric studies. His text became the standard for the ancient world. When Aristarchus thought a part of the poem was wrong, he didn't delete it. Instead, he marked it with special symbols, like an obelus (a line with a dot, like ÷), to show his doubts. This is very helpful for us today!

The Alexandrian scholars had guiding principles for their work:

- Consistency of content: They believed that if parts of the story didn't match up, it meant the text had been changed.

- Consistency of style: If a word or phrase appeared only once in Homer, they often thought it might be an addition.

- No repetitions: If a line or passage was repeated word-for-word, they often rejected one of them.

- Quality: Homer was seen as the greatest poet, so anything they thought was "poor poetry" was rejected.

- Logic: If something didn't make sense (like Achilles nodding at his friends while chasing Hector), they didn't think Homer wrote it.

- Morality: Following Plato's ideas, they believed a poet should be moral. So, if a passage seemed "unsuitable," they thought the real Homer wouldn't have written it.

- Explaining Homer from Homer: Aristarchus's motto was to solve problems in Homer by looking at other parts of Homer's own work, rather than using outside information.

Today, we know that these rules can be too strict. Poets often use "poetic licence" (creative freedom) and might repeat things or use unusual words on purpose. But these ancient scholars set the stage for how we study texts even now.

Allegorical Interpretations

Some scholars, especially the Stoics (an ancient philosophy group), liked to interpret Homer's poems as allegories. This means they believed the stories had a hidden, deeper meaning, often about philosophy or how the world works.

For example, one note on the Iliad explains the battle of the gods as a symbol of different elements and ideas fighting each other. So, Apollo (god of light) might be against Poseidon (god of the sea) because fire is against water.

This way of interpreting Homer continued to be popular with scholars in the Byzantine Empire (the eastern Roman Empire). However, since the Middle Ages, interpreting non-allegorical literature as allegory hasn't been common. Modern scholars often find these interpretations less useful.

1700s and 1800s: New Ideas

The 1700s and 1800s brought big changes to Homeric scholarship. The "Homeric question" became a major debate: Who exactly was Homer, and how did his poems come to be?

One important discovery was made by Richard Bentley in 1732. He found traces of an old Greek letter called the "digamma" in Homer's text. This letter was used in earlier Greek but disappeared later. Bentley showed that many of the "mistakes" in Homer's rhythm could be explained by the presence of this lost letter.

Another key development was the publication of the A and B scholia on the Iliad by Jean-Baptiste-Gaspard d'Ansse de Villoison in 1788. These old notes helped scholars understand the history of the poems.

The Homeric question really took off with Friedrich August Wolf's book, Prolegomena ad Homerum, in 1795. He argued that the poems were first created in the 900s BCE and passed down orally (by speaking and singing, not writing). He believed they changed a lot over time as bards performed them and editors adapted them. He also thought the poems only became a unified story after they were finally written down.

Wolf's ideas led to two main groups of scholars: the Analysts and the Unitarians.

Analysts: Many Authors?

19th-century Analysts believed that the Homeric epics were put together by many different people. They saw them as a mix of original genius and later additions or poor editing. Some even thought the Iliad and Odyssey were written by different poets. They were like the ancient scholar Zoilus, who looked for inconsistencies.

For example, Karl Lachmann argued in 1847 that the Iliad was a collection of 18 separate folk songs. He thought that different parts of the poem were originally independent stories that were later combined.

Another Analyst, Wilamowitz, published important studies in 1884 and 1927. He believed the Odyssey was put together around 650 BCE from three separate poems by an "editor." He thought this editor then added more small changes. Analysts often linked parts of the poems they thought were "poor" to these later additions.

Unitarians: One Great Poet!

The Unitarians were the opposite of the Analysts. They believed that the two Homeric epics showed a strong artistic unity, meaning they were the work of a single great mind – Homer.

Gregor Wilhelm Nitzsch was one of the first scholars to argue against Wolf. He believed the poems were unified and explored how they related to other lost epic poems about the Trojan War.

Many Unitarian scholars focused on appreciating the poems as great works of art. They also studied the archaeology and social history of Homeric Greece from a Unitarian point of view. For example, Heinrich Schliemann, who excavated the ancient city of Troy in the 1870s, treated Homer's poems as a historical source.

What Analysts and Unitarians Agreed On

Analysts often studied the language and text very closely, much like the ancient Alexandrian scholars. Unitarians were more like literary critics, enjoying the artistry of the poems.

But both groups shared a common goal: to honor Homer as a great, original genius. They both believed that everything good in the epics came from him. So, Analysts looked for mistakes and blamed them on bad editors, while Unitarians tried to explain away any errors, sometimes even saying they were actually brilliant!

Both groups inherited the idea from the Alexandrians that "good" poetry was "authentic" (by Homer), and "shoddy" poetry was "interpolated" (added later).

20th Century: New Ways of Thinking

In the 20th century, Homeric scholarship was still influenced by the Analyst and Unitarian debate. However, two new and very important ways of thinking emerged: "Oral Theory" and "Neoanalysis." These two ideas are not against each other; in fact, they often work together.

Oral Theory: Stories Told, Not Written

Oral Theory (or Oralism) studies how Homer's poems were passed down by word of mouth, focusing on their language, culture, and literary style. It looks at both the language and the artistic side of the poems.

The main figures behind Oralism are Milman Parry and his student Albert Lord. Parry, a linguist, compared Homeric epic to living oral traditions of epic poetry. In the 1930s and 1950s, he and Lord recorded thousands of hours of epic poems being performed orally in Yugoslavia.

Their work showed several key things:

- Homer's epics share many features with known oral traditions.

- It's possible for long poems like the Iliad and Odyssey to be created and remembered in an oral tradition, thanks to special "formulaic systems" (like set phrases or repeated scenes) that help bards compose and remember.

- Many strange features that bothered ancient scholars and Analysts are probably signs of how the poems changed as they were passed down orally. Poets could even "re-invent" parts of the story during a performance, like jazz musicians improvising on a theme.

Some Oralists believe that Homer's epics were actually created in an oral tradition. Others think they just drew on earlier oral traditions. The joke about 19th-century Analysts was that the epics "were not composed by Homer but by someone else of the same name." Now, the joke about Oral Theorists is that they claim the epics are "poems without an author." Many Oralists would agree with this, meaning the poems grew over time through many performers, rather than being written by a single person.

Neoanalysis: Looking at Earlier Stories

Neoanalysis is different from 19th-century Analysis. It studies how Homer's two epics relate to the Epic Cycle. The Epic Cycle was a group of other ancient Greek poems about the Trojan War that don't survive today, except for summaries and small pieces. Neoanalysis tries to figure out how much Homer used earlier stories about the Trojan War, and how much other poets used Homer's work.

A famous idea in Neoanalysis is the "Memnon theory" by Wolfgang Schadewaldt. This idea suggests that a major part of the Iliad (the story of Achilles getting angry and killing Hector after Patroclus dies) is based on a similar story from one of the Epic Cycle poems called the Aithiopis.

Here's how the stories are similar:

| Aithiopis | Iliad |

|---|---|

| Achilles' friend Antilochus fights bravely. | Achilles' friend Patroclus fights bravely. |

| Antilochus is killed by Memnon. | Patroclus is killed by Hector. |

| An angry Achilles chases Memnon to the gates of Troy and kills him. | An angry Achilles chases Hector around the city walls and kills him. |

| Achilles is then killed by Paris. | (Achilles has been told his own death will happen after Hector's.) |

The debate is about what these similarities mean. Did the poet of the Iliad borrow from the Aithiopis? Why did they do it? And how did these two stories influence each other over time?

In a broader sense, Neoanalysis also tries to reconstruct earlier versions of the Iliad and Odyssey by looking at clues in the surviving texts. For example, some scholars suggest that earlier versions of the Odyssey had Telemachus looking for his father in different places or Penelope recognizing Odysseus much earlier. This shows that Neoanalysis combines the idea of earlier versions (like Analysis) with the understanding of oral traditions (like Oral Theory).

Recent Discoveries and Studies

The exact date when Homer's epics were written down or became fixed is still debated. Many scholars now believe the text of both epics became stable in the late 700s or early 600s BCE. A date of 730 BCE is often suggested for the Iliad.

Since the 1970s, new ways of understanding literature, called literary theory, have influenced how scholars interpret Homer. For example, some studies look at how storytelling works in the Odyssey.

One important area is narratology, which is the study of how stories are told. This combines looking at language with literary criticism. Scholars like Irene de Jong and Egbert Bakker have used narratology to understand how the story is presented in the Iliad and Odyssey, and how the poems use language like speech.

See also

- Epic Cycle

- Homer

- Homeric Question

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |