Lamprey facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Lamprey |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Sea lamprey in Sweden | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: |

Petromyzontiformes

|

| Family: |

Petromyzontidae

|

| Subfamilies | |

|

Geotriinae |

|

Lampreys are a very old group of jawless fish. They belong to the group called Petromyzontiformes. Adult lampreys have a special mouth that looks like a funnel with teeth, which they use for sucking. The name "lamprey" probably comes from a Latin word that might mean "stone licker."

There are about 38 known types of lampreys alive today. The most famous ones are the "parasitic" types. These lampreys attach to other fish and suck their blood. However, only 18 species actually do this. Nine of these parasitic species live in both fresh and salt water (they are anadromous), while the other nine live only in fresh water. All the lampreys that are not parasitic live only in fresh water. Parasitic lampreys also attach to bigger animals to get a free ride. Adult lampreys that are not parasitic do not eat. They live off the food they stored when they were young, worm-like larvae called ammocoetes, which they got by filter feeding.

Contents

Where Do Lampreys Live?

Lampreys mostly live in coastal waters and fresh water. Some species, like the pouched lamprey and sea lamprey, travel long distances in the open ocean. Some types of lampreys are also found in lakes that are not connected to the sea. You can find lampreys in most mild climate areas, but not in Africa. Their young larvae, called ammocoetes, cannot handle very warm water. This is why you won't find lampreys in tropical places.

Too much fishing and pollution can harm lamprey populations. For example, in Britain, lampreys used to be found far up the River Thames. Now, because the Thames and River Wear are cleaner, lampreys have been seen again in London.

Dams and other building projects can also hurt lampreys. They block the paths lampreys use to migrate and reach their spawning grounds. On the other hand, building new water channels has created new homes for them. In North America, sea lampreys have become a big problem in the Great Lakes because of this. Programs to control lampreys are changing because of worries about drinking water quality in some areas.

Lamprey Biology

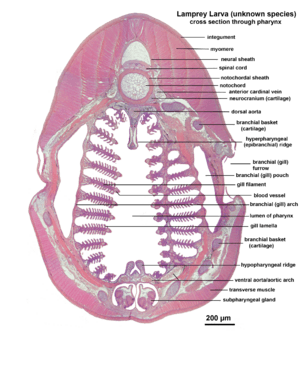

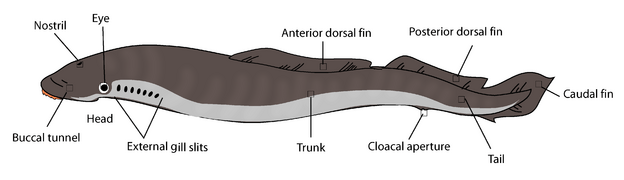

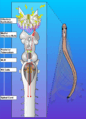

Adult lampreys look a bit like eels. They have long bodies without scales and can grow from about 13 to 100 centimeters (5 to 40 inches) long. They do not have paired fins. Adult lampreys have large eyes, one nostril on top of their head, and seven gill openings on each side of their head. Inside their throat, the lower part forms a breathing tube that is separate from their mouth.

This special design helps adult lampreys feed. It stops the fluids from their prey from escaping through their gills. It also keeps the prey's fluids from getting in the way of breathing. Lampreys breathe by pumping water in and out of their gill pouches, instead of taking it in through their mouth. Their eyes are near their gills. In young larvae, the eyes are not well developed and are hidden under the skin. The eyes fully develop when the lamprey changes into an adult.

Lampreys have a cartilaginous skeleton, which means it's made of tough, flexible tissue, not bone. This suggests they are a very ancient group of vertebrates (animals with backbones). Instead of true backbones, they have a series of cartilage structures called arcualia. These are arranged above their notochord, which is a flexible rod that supports their body.

Studies show that lampreys are very good swimmers. Their swimming movements create low-pressure areas around their bodies. This actually pulls them through the water instead of pushing them.

The earliest lampreys were likely specialized to feed on the blood and body fluids of other fish after they changed into adults. They attach their mouths to an animal's body. Then, they use three tough plates on their tongue to scrape through the skin until they reach blood or other fluids. The teeth on their mouth disc mainly help them stay attached to their prey. These teeth have a hollow center, allowing new teeth to grow underneath the old ones. Some lampreys that used to feed on blood have changed. Some now eat both blood and flesh. Others have become specialized to eat only flesh and can even go inside the host's organs. Flesh-eating lampreys can also use their mouth disc teeth to cut out tissue. They have smaller glands in their mouths because they don't need to make blood thinner all the time. They also have ways to stop solid food from getting into their gill pouches, which could block their gills. Studies of lamprey stomach contents have found parts of intestines, fins, and bones from their prey. While lampreys can attack humans, they usually only do so if they are very hungry.

Non-parasitic lampreys developed from parasitic ones. Sometimes, very large individuals of the otherwise small American brook lamprey have been seen. This suggests that some non-parasitic lampreys might sometimes go back to the parasitic way of life of their ancestors.

Research on sea lampreys shows that adult males use a special heat-producing tissue to attract females. This tissue is a ridge of fat cells near their front dorsal fin. After a male attracts a female with special scents (pheromones), the heat the female feels when they touch encourages them to lay eggs.

Lampreys are important for understanding adaptive immune systems. They have an immune system that works like the one in higher vertebrates, with cells similar to T cells and B cells.

Northern lampreys have the most chromosomes (164–174) among all vertebrates.

Pouched lamprey larvae can handle a lot of free iron in their bodies. They have strong systems to get rid of large amounts of these metal ions.

Lampreys are the only living vertebrates that have four eyes. Most lampreys have two extra parietal eyes: a pineal and a parapineal eye. The only exception is the Mordacia group.

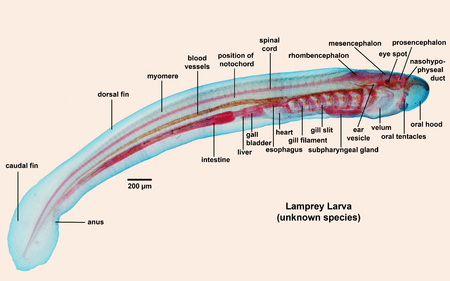

Lamprey Life Cycle

Adult lampreys lay their eggs in nests made of sand, gravel, and pebbles in clear streams. After the eggs hatch, the young larvae, called ammocoetes, float downstream with the current. They stop when they reach soft, fine sediment in silt beds. There, they burrow into the silt, mud, and decaying plants. They live as filter feeders, eating tiny bits of plants, algae, and microorganisms. The eyes of the larvae are not fully developed, but they can tell when the light changes. Ammocoetes can grow from about 8–10 cm (3–4 inches) to about 20 cm (8 inches). Many species change color during the day, becoming dark in the daytime and pale at night. Their skin also has light-sensitive cells, mostly in their tail, which helps them stay buried. Lampreys can spend up to eight years as ammocoetes. However, some species, like the Arctic lamprey, only spend one to two years as larvae. After this, they go through a change called metamorphosis, which usually takes 3-4 months. During this time, they do not eat.

The ammocoetes filter water very slowly, slower than any other animal that filter feeds. Because of this, they need water that is rich in nutrients to get enough food. Most animals that filter feed can live in water with less than 1 mg of suspended organic solids per liter. But ammocoetes need at least 4 mg/l, and in their homes, concentrations have been measured up to 40 mg/l.

During metamorphosis, the lamprey loses its gallbladder and the tube that carries bile. Also, a part of its body called the endostyle changes into a thyroid gland.

Some lamprey species, including those that are not parasitic, live in fresh water for their whole lives. They lay eggs and die soon after changing into adults. However, many species are anadromous. This means they migrate to the sea. They start to feed on other animals while still swimming downstream after their metamorphosis. This change gives them eyes, teeth, and a sucking mouth. The anadromous lampreys are parasitic, feeding on fish or marine mammals.

Anadromous lampreys spend up to four years in the sea. Then, they migrate back to fresh water to lay eggs. Adults build nests, called redds, by moving rocks. Females release thousands of eggs, sometimes up to 100,000. The male wraps around the female and fertilizes the eggs at the same time. Both adults die after the eggs are fertilized, as they only reproduce once in their lives (this is called being semelparous).

Lampreys as Food

People have eaten lampreys for a long time. The ancient Romans really liked them. During the Middle Ages, people from the upper classes all over Europe ate them a lot. They were especially popular during Lent, when eating meat was not allowed, because they tasted and felt like meat. King Henry I of England was supposedly so fond of lampreys that he ate them often, even when he was old and sick, against his doctor's advice. It is said he died from eating too many lampreys, but we don't know for sure if that was the real cause.

On March 4, 1953, Queen Elizabeth II's coronation pie was made by the Royal Air Force using lampreys.

In southwestern Europe (Portugal, Spain, and France), northern Finland, and Latvia, larger lampreys are still a very special delicacy. Sea lamprey is the most popular type in Portugal. Too much fishing has reduced their numbers in these areas. Lampreys are also eaten in Sweden, Russia, Lithuania, Estonia, Japan, and South Korea. In Finland, they are often sold pickled in vinegar.

The mucus and serum (a part of the blood) of several lamprey species can be toxic. This includes the Caspian lamprey, river lampreys, and sea lamprey. They need to be cleaned very well before cooking and eating.

In Britain, lampreys are often used as bait for fishing, usually as dead bait. Fish like Northern pike, perch, and chub can all be caught using lampreys. You can buy frozen lampreys from most bait and tackle shops.

Images for kids

-

The lamprey's light-colored underside and darker back allow it to blend in when viewed from above or below, an example of countershading

-

Several species of European lampreys

-

Jamoytius kerwoodi, a putative lamprey relative from the Silurian

-

Lampreys attached to a lake trout.

-

Illustration from an edition of Tacuinum Sanitatis, 15th century