Ivan Cankar facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

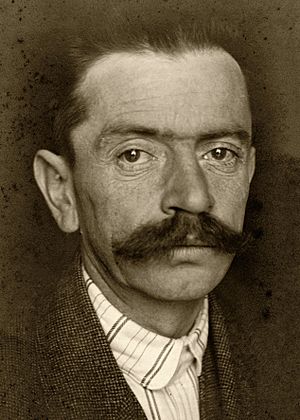

Ivan Cankar

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 10 May 1876 Vrhnika, Austria-Hungary (today Slovenia) |

| Died | 11 December 1918 (aged 42) Ljubljana, Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (now the capital of Slovenia) |

| Occupation | Writer, essayist, playwright, poet, political activist |

| Genre | plays, short stories, short novels, essays |

| Literary movement | Symbolism, Modernism |

Ivan Cankar (born May 10, 1876 – died December 11, 1918) was a famous Slovene writer, who also wrote plays, essays, and poems. He was also a political activist, meaning he worked to bring about social or political change.

Many people see him as one of the most important writers in the Slovene language. He is often compared to other great writers like Franz Kafka and James Joyce. Ivan Cankar, along with Oton Župančič, Dragotin Kette, and Josip Murn, helped start a new style of writing called modernism in Slovene literature.

Contents

Biography

Ivan Cankar was born in Vrhnika, a town in Carniola near Ljubljana. He was one of many children in a poor family. His father moved to Bosnia soon after Ivan was born. His mother, Neža Cankar, raised him. Their relationship was very close but also complicated. His mother's image, as someone who sacrificed a lot, often appeared in Cankar's stories later on.

After finishing school in his hometown, he went to the Technical High School in Ljubljana from 1888 to 1896. During this time, he started writing poetry. He was inspired by poets like France Prešeren and Heinrich Heine. In 1893, he discovered the long poems of Anton Aškerc. This greatly influenced his writing style and ideas. Because of Aškerc, Cankar stopped writing sentimental poetry. He started writing in a more realistic way and supported ideas of national liberalism, which focused on national identity and individual freedoms.

In 1896, he went to the University of Vienna to study engineering. But he soon changed his studies to Slavic languages. In Vienna, he began living a "bohemian" lifestyle, which means he lived in a free-spirited, artistic way, often without much money. He was influenced by new European writing styles like decadentism (focus on beauty and artificiality), symbolism (using symbols to represent ideas), and naturalism (showing life as it really is). He became friends with Fran Govekar, another young Slovene writer.

Between 1897 and 1899, Cankar's main ideas were based on positivism, which means focusing on scientific facts. In 1897, he moved back to Vrhnika. After his mother died that autumn, he moved to Pula. In 1898, he returned to Vienna, where he lived until 1909.

Political Views and Activism

While in Vienna for the second time, Cankar's ideas changed quickly. In a letter to the Slovene writer Zofka Kveder in 1900, he said he no longer believed in positivism and naturalism. He started to believe in spiritualism and idealism. He also became very critical of Slovene liberalism. He slowly moved towards socialism, a political idea that focuses on equality and community. He was influenced by Janez Evangelist Krek, a Slovene priest who believed in social activism based on Christian values.

Cankar joined the Yugoslav Social Democratic Party. This party was active in the Slovene regions and Istria. In 1907, he ran for election to the Austrian Parliament in a working-class area. However, he lost the election.

In 1909, he left Vienna and moved to Sarajevo in Bosnia and Hercegovina. His brother Karlo, a priest, lived there. During this time, Cankar became more open to Christian spirituality. Later that year, he settled in the Rožnik area of Ljubljana. He remained an active member of the Yugoslav Social Democratic Party. However, he disagreed with the party's idea of combining Slovene culture and language with Serbo-Croatian ones to create a single Yugoslav culture. Cankar strongly believed that Slovenes should keep their own unique national and linguistic identity.

After his election loss in 1907, Cankar started writing many essays to explain his political and artistic ideas. After returning to Carniola in 1909, he traveled around the Slovene lands, giving lectures. Two of his most famous lectures were "The Slovene people and the Slovene culture" (in Trieste, 1907) and "Slovenes and Yugoslavs" (in Ljubljana, 1913). In the second lecture, Cankar supported the idea of all South Slavs uniting politically. However, he did not want their cultures to merge. Because of this lecture, he was sent to prison for a week for speaking against the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy.

When World War I started in 1914, he was again put in Ljubljana Castle because people thought he supported Serbia. But he was released soon after. In 1917, he was called to join the Austro-Hungarian Army, but he was sent home due to poor health. In his last lecture, given in Trieste after the war ended, he asked for a moral renewal in Slovene politics and culture. He moved to the center of Ljubljana, where he died in December 1918. He died from pneumonia, which was a complication of the Spanish flu pandemic. Many people attended his funeral, including important cultural and political figures. In 1936, his grave was moved to the Žale cemetery in Ljubljana, where he was buried next to his friends and fellow writers, Dragotin Kette and Josip Murn.

Works and Literary Style

Ivan Cankar wrote about 30 books. He is seen as one of the main writers of Slovene modernist literature. This style of writing often explores new ways of expressing ideas. Cankar's works often dealt with social issues, national identity, and moral questions. In Slovenia, his most famous works are the play Hlapci ("Serfs"), the funny play Pohujšanje v dolini Šentflorijanski (Scandal in St. Florian Valley), and the novel Na klancu (On the Hill).

However, his short stories and sketches are also very important. They combine symbolism, modernism, and even expressionism (a style that shows emotions rather than reality). This mix makes his writing very unique.

Early Works

Cankar started as a poet. He published his first poems as a teenager in the magazine Ljubljanski zvon. In Vienna, he met other young Slovene artists and writers, like Oton Župančič. They introduced him to new European literary trends. In 1899, Cankar published his first poetry collection called Erotika. This book showed influences of decadentism and sensualism, which focus on beauty and sensory experiences. The bishop of Ljubljana, Anton Bonaventura Jeglič, was so shocked by the book that he bought all copies and had them destroyed! A new edition came out three years later. By then, Cankar had stopped writing poetry and started writing more about politics and society.

In 1902, he wrote his first play, Za narodov blagor (For the Welfare of the Nation). This play was a strong parody, or humorous imitation, of the liberal nationalist leaders in the Slovene lands. The same year, he published the short novel Na klancu (On the Hill). In this book, he wrote about the struggles of poor rural workers and the difficult lives of ordinary people. The novel used a realistic style mixed with allegory (stories with a hidden meaning) and a unique, almost biblical writing style. This book brought him wide recognition.

Later Works and Themes

In his novels Gospa Judit (Madame Judit), Hiša Marije Pomočnice (The Ward of Mary Help of Christians), and Križ na gori (Cross on the Mountain), all published in 1904, Cankar explored spiritual and idealistic themes. He continued to focus on oppressed people and their dreams for a better life. In 1906, he wrote the short novel Martin Kačur, which was about an idealist who failed.

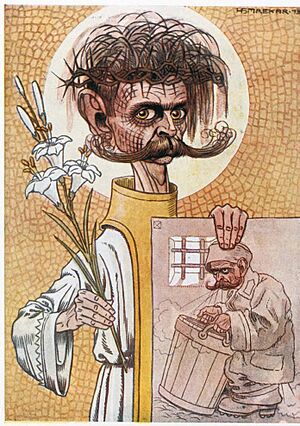

During the 1907 elections, he published the short story Hlapec Jernej in njegova pravica (The Servant Jernej and His Justice). This story describes a conflict between a worker and both the capitalist system and traditional society. The worker cannot understand their rules. After the Slovene People's Party won the election, Cankar wrote his most important play, the satire Hlapci (Serfs). In this play, he made fun of public servants who used to be progressive but then changed to support Catholicism after the liberal party lost. Both the liberal and Catholic parties in Slovenia strongly disliked the play. It was not performed until after Austria-Hungary broke apart in 1918.

In the play Pohujšanje v dolini Šentflorjanski (Scandal in St. Florian Valley, 1908), Cankar made fun of the strict morals and old-fashioned thinking of small-town society in Carniola. Cankar was also known for his essays, which showed his great writing skill and use of irony.

His last collection of short stories, Podobe iz sanj (Images from Dreams), was published after he died in 1920. These stories are like magically realistic and allegorical pictures of the horrors of World War I. They show a clear shift from symbolism to expressionism and are considered some of Cankar's best poetic prose.

Personality and World View

Cankar was a sensitive person, both emotionally and physically. However, he had a very strong and determined mind. He was a sharp thinker who could criticize both the world around him and himself. He was full of contradictions and loved to use irony and sarcasm. He was also very emotional and sensitive to questions of right and wrong. He looked deeply into his own thoughts and feelings. His works are often about his own life and are famous for their honest look at his own actions and mistakes.

Cankar grew up as a Roman Catholic. In high school, he became a "freethinker," someone who forms their own opinions rather than accepting traditional beliefs. He questioned religious rules and preferred the scientific explanations of his time. Between 1898 and 1902, he was influenced by thinkers like Ralph Waldo Emerson and Friedrich Nietzsche. He found the idea of a "world soul" in the writings of the Belgian poet Maurice Maeterlinck. This idea suggested that individual souls are connected to a larger world soul, and Cankar used this in his own works.

Around 1903, he developed his own unique interpretation of Marxism, a political and economic theory. Later in his life, especially after 1910, he gradually moved towards traditional Christianity. Even though he never officially left his Catholic faith, he was generally seen as agnostic, meaning he wasn't sure if God existed, but he still liked some parts of traditional Catholic devotion.

Influence

Cankar was an important writer even during his lifetime. His books were widely read, and he was the first Slovene writer who could earn a living only from writing. He became even more influential after he died. He strongly believed in the unique culture and identity of the Slovene people. Because of this, he became a hero for young Slovene thinkers who disagreed with the centralizing policies of the Serb leaders in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. In the early 1920s, a group of young Catholics, who believed in Christian Socialism, named their journal Križ na gori (Cross on the Mountain) after one of Cankar's novels. This group, known as the "Crusaders," helped start the Christian left movement in Slovenia in the 1920s and 1930s.

Cankar's work and ideas influenced all three major literary styles in Slovene literature between 1918 and 1945. These included expressionism (showing emotions), social realism (showing real life and social issues), and avant-gardism (new and experimental art). His political ideas also influenced Slovene politicians and thinkers. Cankar's deep psychological insights became a major source for understanding the Slovene national character.

During the rule of King Alexander (1929–1934), Cankar's works were removed from school lessons. This was because he was seen as a dangerous supporter of Slovene uniqueness and nationalism. After 1935, his status as one of the greatest Slovene writers was never seriously questioned. In 1937, the first complete collection of Cankar's work was published. After World War II, a publishing house called Cankarjeva založba (Cankar Press) was created to publish his collected works.

Cankar was especially important as a playwright. He is considered the founder of modern Slovene theater. He has influenced almost all Slovene playwrights who came after him. Many contemporary Slovene playwrights still show a clear influence from Cankar's ideas. Many important Slovene thinkers have also studied Cankar's works.

Even during his life, his works were translated into German, Czech, Serbian, Croatian, Finnish, and Russian. His work has also been translated into French, English, Italian, Hungarian, and many other languages. Cankar's influence outside Slovenia has been small. However, some non-Slovene authors were influenced by him. For example, the famous German writer Thomas Mann liked Cankar's novel Hiša Marije Pomočnice and helped publish a German edition in 1930.

Legacy

Today, Cankar's writing style is still seen as one of the best examples in the Slovene language. His influence as a novelist has decreased since the 1960s. However, his plays are still very popular in Slovene theaters.

Many streets, squares, public buildings, and organizations have been named after Ivan Cankar. During World War II, two military units of the Slovene Partisans were named after him: the Cankar Brigade and the famous Cankar Battalion. Since the 1980s, Slovenia's largest convention center, Cankar Hall in Ljubljana, has carried his name. From 1994 to 2007, Cankar's picture was on the 10,000 Slovenian tolar banknote.

See also

In Spanish: Ivan Cankar para niños

In Spanish: Ivan Cankar para niños

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |